In an age where algorithms can generate moving images and voices, and even facts, what remains true? This article takes a look at art, AI and responsibility, and considers how we renegotiate truth in the age of artificial intelligence.

“You’d never assume a piece of text is true just because someone wrote it down. You go investigate the source. Videos used to be different because they were harder to fake. That’s over now.“

www.bbc.com/future/article/20251031-the-number-one-sign-you-might-be-watching-ai-video

Recently, a video of a king caused a stir—and not just on social media. The president of a democratic state was portrayed as a monarch heroically fighting his enemies. Polished, pathos, propaganda—and completely artificial.

In 2025, this hardly surprises us anymore. Although this video is still clearly recognizable as fake, partly because the content is absurd, with SORA 2, the latest video AI from OpenAI, anyone can now create hyper-realistic scenes in a matter of seconds. What used to require expensive film studios can now be created at the touch of a button – flooding our feeds with moving images that look deceptively real but have nothing to do with reality.

What’s new about SORA 2 is not only its technical brilliance, but also its social embedding: for the first time, an AI generator is no longer an isolated tool like DALL·E or SORA 1, but part of a social media platform. OpenAI has deliberately released SORA 2 as an app with chat functionality, community rules, and public interaction logic – thus completing the transition from the production to the distribution of truth. AI is no longer just a tool, but part of the digital discourse itself, in which truth is negotiated, shared, and renegotiated – a turning point for our society.

The more realistic these fictions become, the more fragile our trust in what we see becomes. “Once you lie, no one believes you” is the credo. What does this mean for our sense of truth? For our journalistic discourse, our cultural memory, our social orientation? And how problematic is it for us, as humans, when we can no longer believe anything or anyone?

„Welcome to the era of fakery. The widespread use of instant video generators like Sora will bring an end to visuals as proof.“

Brian X. Chen in NY Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/09/technology/personaltech/sora-ai-video-impact.html

What’s True? — Disorientation in the Age of Synthetic Content

AI has long since found its way into art, especially media art. At Ars Electronica, AI is not seen as a substitute for human narrators and their creativity, but rather as a tool for reflection—a medium that forces us to rethink the mechanisms of perception, power, and truth—and as a collaborative aid that supports artists in telling and developing their stories.

This understanding is evident in numerous projects: from artistic explorations of algorithmic control and data ethics to immersive installations.

The End of Seeing — When Seeing is No Longer Believing

“Our brains are wired to believe what we see — but we must now learn to pause and think.“

Ren Ng, University of California, Berkeley

Since the dawn of humanity, seeing has been considered proof. “Pics or it didn’t happen” was the undisputed credo of a visual culture that trusted images. But with generative AI, this paradigm is finally collapsing: “Nothing you see is real.”

AI images and videos destroy the evidence of sight. Dashcam recordings, deepfakes featuring Martin Luther King Jr., or deceptively real fake news clips—they all undermine the idea of a shared visual truth. A society that urgently needs consensus thus loses its foundation: trust in perception. Or: When the eye can no longer distinguish what is real, critical questioning must take over—a skill that is becoming the new and most important cultural competence for navigating our everyday lives.

Even the icons of our time are not spared: Martin Luther King’s famous impassioned speech at the March on Washington, or: The image of the Pope in a white Balenciaga coat went around the world in 2023 – an AI-generated meme that fascinated and unsettled millions.

For artist Martyna Marciniak, this image was the starting point for her work “Anatomy of Non-Fact”. Using forensic, technical, visual, and historical analyses, she examines how fiction and fact become indistinguishable. Following Jean Baudrillard – “proving the real through the imaginary, art through anti-art” – she searches for a new “aesthetics of facts.”

The first chapter of her nearly 18-minute video focuses on the fake Balenciaga pope. Marciniak dissects the mechanisms of AI generation, journalistic imagery, and digital cloning—and lets the artificial pope himself reflect on the nature of truth. In this way, the synthetic image becomes a mirror of our own crisis of perception.

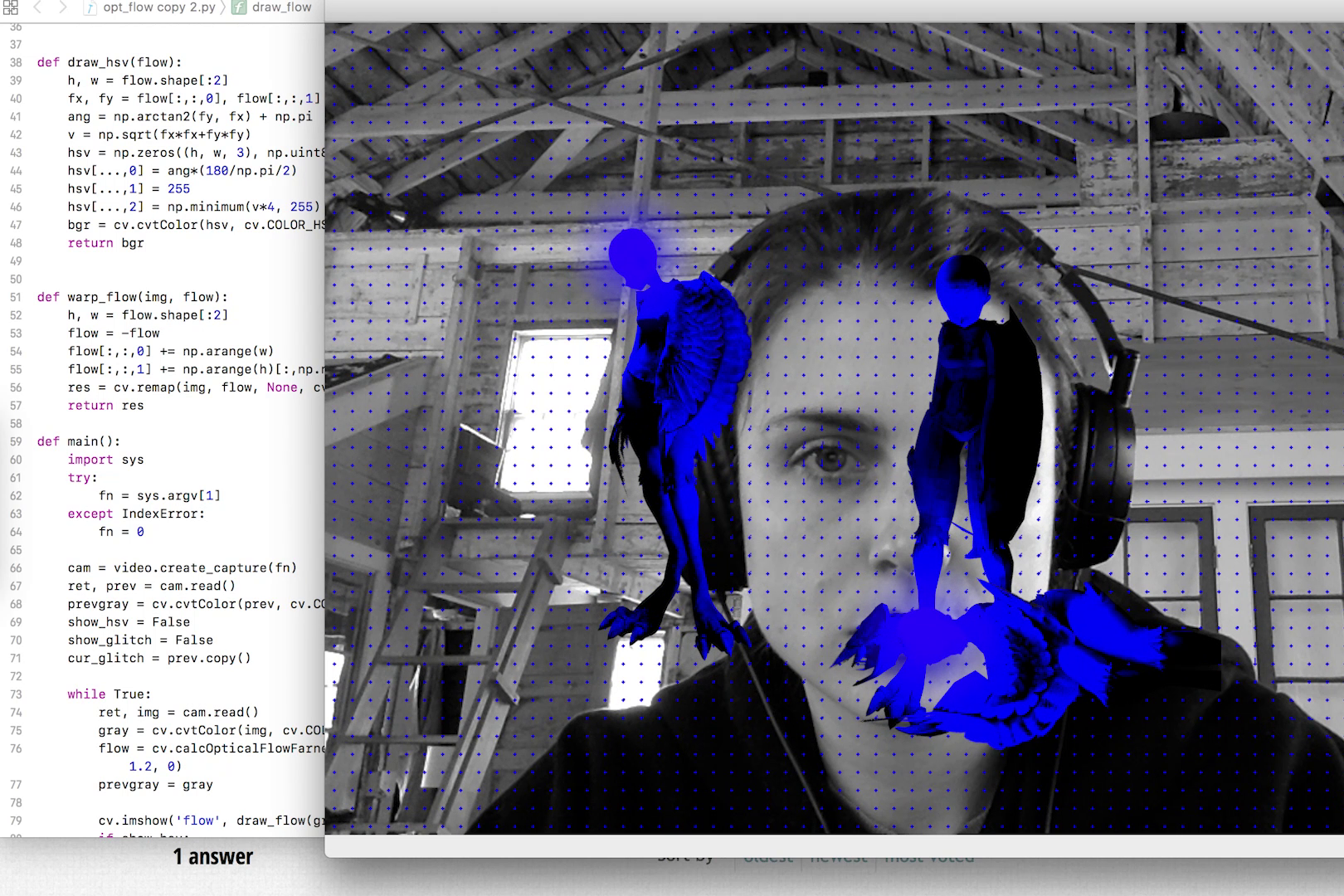

Rachel Rossin’s work “Recursive Truth” also responds to the era of generative images—and uses their own means against them. Using video game mods, OPENCV libraries for facial recognition, and deepfake techniques, Rossin explores how memory, loss, and truth arise and decay in digital systems. In her 2:55-minute loops, graphic errors and code bugs reveal the fragility of memory—they destroy the game or mutate into pure visual glitches.

The Collapse of Consensus — Democracy without a Shared Reality

„Without facts, you can’t have truth; without truth, you can’t have trust.

Maria Ressa, Athens Democracy Forum

Without these three, we have no shared reality. You cannot have democracy.“

Democracy does not thrive on unity, but on the fact that we share the same reality—even if we may disagree about it. Democracy does not die when we disagree, but when we no longer speak of the same reality.

This is precisely where the problem with generative AI begins – it and our human perception of the generated content represent a potential attack on our democratic self-image. Here, we must distinguish between two aspects: First, falsifying content – be it text, images, or videos – has long been possible, but it was time-consuming and difficult, which is why it was relatively rare. With generative AI, anyone can now do this in a matter of seconds and achieve professional results – that is new. Second, social media, in which these AI generators are embedded, ensures the immediate and mass dissemination of such content. When alleged facts can be produced at will and there is no longer a consensus on reality, the public sphere is in danger of disintegrating. Emotions are algorithmically amplified, information spaces fragment, and debates lose their common ground.

The Social Media Watchblog describes, with a view to the 2024 US election, that a fragmented public sphere has replaced common debate. Influencers have become the new gatekeepers, while – as Maria Ressa says – “an atomic bomb has exploded in our information ecosystem.”

Nandita Kumar’s work “From Paradigm to Paradigm, into the Biomic Time” fits into this context: it shows how manipulated and repeated misinformation distorts our perception of the environment and reality. Kumar transforms these “false facts” into algorithmically generated sound and text fragments—an aesthetic metaphor for the loss of shared truth. She makes it audible how disinformation erodes trust, deepens social division, and increasingly blurs the boundaries between knowledge and belief.

Artist Andy Gracie also addresses this theme in his work Massive Binaries, which was shown at the Ars Electronica Festival 2023 and was created as part of the Randa Art|Science Residency (Institut Ramon Llull & Ars Electronica).

Two neutron stars orbiting each other serve as a metaphor for a polarized, divided society: “science believers vs. deniers,” “left vs. right.” Like the stars, the camps approach each other, repel each other, and finally collide—a symbol of the loss of shared reality. Gracie shows AI in a dual role: as a tool for knowledge in scientific data analysis and as a distorter of truth in the form of fake news and ideological echo chambers. The same technology can promote knowledge or reinforce disinformation.

In Massive Binaries, two AI-generated figures discuss endlessly with (or rather against) each other—an aesthetic symbol of the algorithmic polarization of public debates. The work thus becomes a poetic-scientific allegory for the collapse of consensus: truth becomes an orbit of competing realities—driven, amplified, and distorted by AI.

The Human in the Loop – Reporting Between Algorithms and Responsibility

One of the greatest fears we humans have about artificial intelligence is that we will lose control. That technology will no longer be a tool, but an actor—a system that takes on a life of its own, reproduces biases in data sets, and thus magnifies errors.

This tension is particularly evident in journalism—where facts should actually be verified rather than generated. What happens when news is no longer researched but synthetically generated?

APA editor-in-chief Katharina Schell sums it up: “AI can support journalism, but it cannot replace it. Human in the loop remains a must.” She thus describes the central principle: humans (or journalists) must not disappear from the loop. They remain the corrective, the responsible party, the interpreter of truth. When dealing with generative content, she, like many others in her industry, proposes a change in strategy: “Fight fire with fire!” Use the same technology to expose your own products. Journalistic tools should automatically recognize AI-generated texts and expose images or videos based on formal and semantic patterns.

The Reporter’s Guide to Detecting AI-Generated Content, for example, lists seven categories of such clues – from anatomical inconsistencies in images to faulty contextual logic – to be used as a manual, a tool that works with the same precision as the technology it checks. Whether this is a practical – and, not least, time-saving – approach remains to be seen.

However, belief in the relevance and importance of professional journalism, in its values and principles, is not “lost,” as a study by the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) shows, because with the increase in fake news, the value of trust and quality journalism also rises. What becomes more precious because it is rarer gains in importance.

The project “The AI Truth Machine” exemplifies this tension. In a fictional court case, it contrasts human and algorithmic judgment and asks: Can a machine recognize truth?

To this end, before being questioned by the “AI truth machine,” a person is asked to lie about a given topic. The AI-supported process of finding the truth differs from judicial questioning methods in its extremely precise analysis of eye movements and pupil changes during an interrogation. After completing the interrogation, the result is presented and the question of whether AI can actually replace a judge is to be clarified.

The work shows that truth cannot be automated. The decisive factor remains who controls, interprets, and is responsible for the systems, and it reminds us that there must always be a human being between the algorithm and the judgment, between the data and the interpretation.

The attitude that follows from this is as simple as it is essential: AI should be a tool, even in journalism—but not the lens through which we see the world. It can structure data, but it cannot take responsibility, and it cannot produce truth, because truth only emerges when people question, examine, and weigh facts.

The Accountability Gap — Who is Accountable in the Sphere of AI?

“AI systems are being built and deployed without responsible decision-makers behind them: algorithms decide, but no one is held accountable.“

Timnit Gebru in https://www.wired.com/story/rewired-2021-timnit-gebru/

A question that runs through all debates surrounding AI is that of responsibility. In professional journalism, it is clearly defined who is liable for content: journalists, editorial offices and publishers. However, in the world of generative systems and social platforms, these boundaries are becoming increasingly blurred. With AI-generated texts, images or videos, it is often impossible to determine who created or distributed them. While responsibility is personified in journalism, in the digital public sphere it usually ends with a disclaimer. Legal regulations such as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act in the US, which largely exempts platforms from liability for published content, exacerbate this imbalance.

This creates a vacuum of responsibility between humans, machines, and media. Who is to blame when disinformation goes viral? The developers? The platforms? Or the users who share what they want to believe?

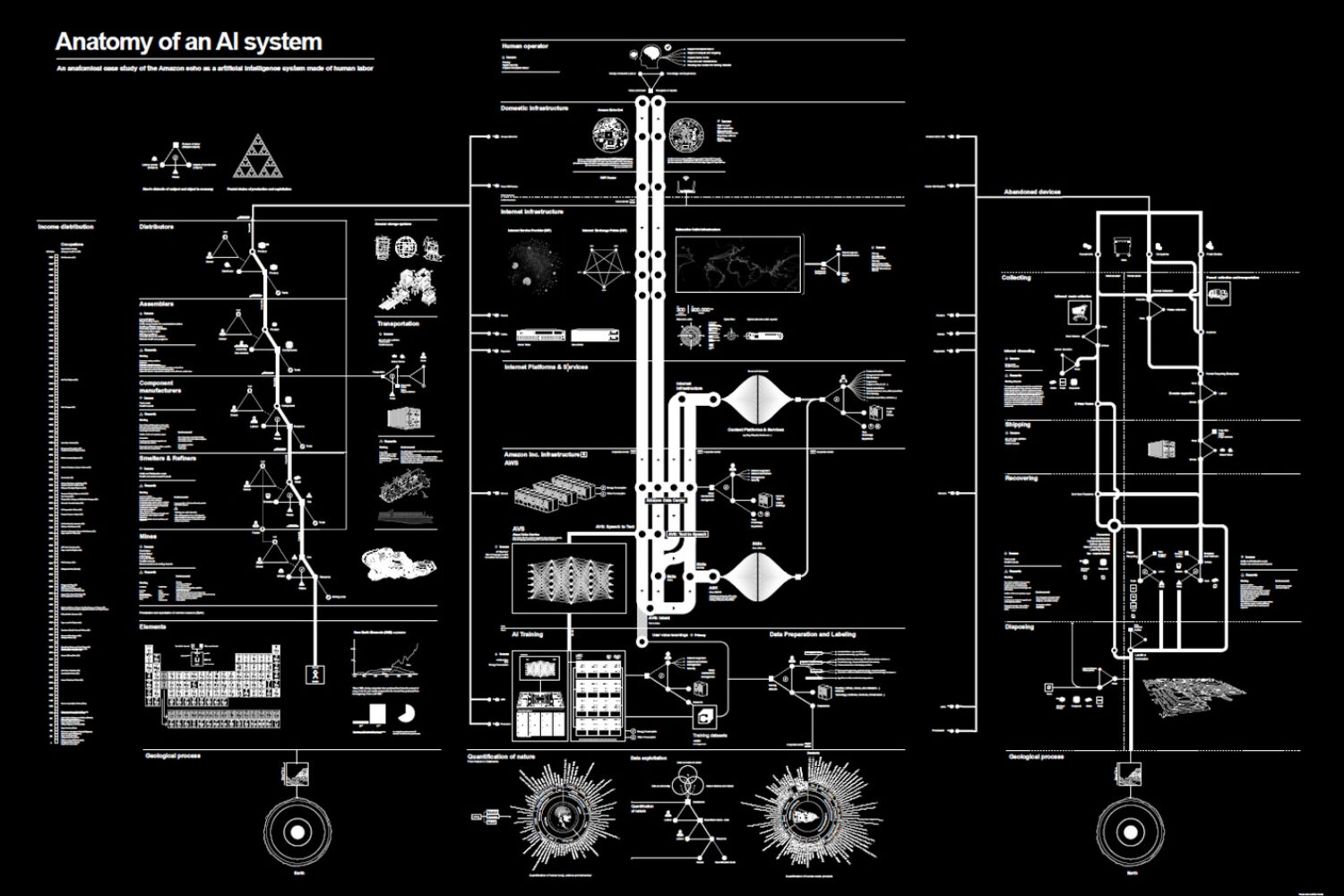

As AI researcher Kate Crawford points out, artificial intelligence is neither artificial nor autonomous:

“AI is neither artificial nor intelligent. It is made from natural resources and it is people who are performing the tasks to make the systems appear autonomous.“

Kate Crawford, The Guardian, 2021

Kate Crawford reminds us that behind every AI there is human labor, political decisions, and ecological costs—and thus also responsibility. Her project “Anatomy of an AI System” (2018, with Vladan Joler) makes these invisible structures visible: Using Amazon Echo as an example, she maps the global resources, data, and power relations.

In Droning by Marta Revuelta (in collaboration with Laurent Weingart), AI vision becomes a mirror of our gaps in responsibility: a helium-filled airship, inspired by military surveillance blimps, classifies visitors in real time as “enemy combatants” or “neutral civilians.” The system is based on training data from real combat recordings and simulated attack decisions—and reveals how human life is reduced to data points in the algorithm. At this moment, the issue of accountability becomes central: Who bears responsibility when a machine makes a decision? Who is behind the classification and who is behind the consequences? Droning thus focuses not only on technical surveillance, but also on the political-ethical question of which power structures autonomous technologies can realize and relieve.

The New Literacy — Media Literacy as a Democratic Skillset

When machines invent stories, people must learn to read them. This ability—media literacy, critical thinking, trust—is becoming the democratic competence of our time. Or, as Jaro Krieger-Lamina (Austrian Academy of Sciences) emphasizes: “The two decisive factors (in dealing with AI, note) are media literacy and trust.”

This theory is not new, but goes back to the Inoculation Theory of Lewandowsky & Van der Linden: media literacy as a “vaccine against disinformation.” The curriculum must include things such as the promotion of critical thinking, source evaluation, and emotional self-regulation in the flow of information. The most important “firewall” against disinformation is not in the code, but in the mind.

Superpoderosas by Maldita.es is a journalistic and educational project that empowers people to actively recognize and combat disinformation. It combines AI-powered tools with collaborative fact-checking, turning citizens into co-creators of an informed public sphere. The aim is not only to expose false content, but also to teach people to take a critical approach to digital information. The project combines technology, education, and community to strengthen trust, responsibility, and awareness of truth in the digital society.

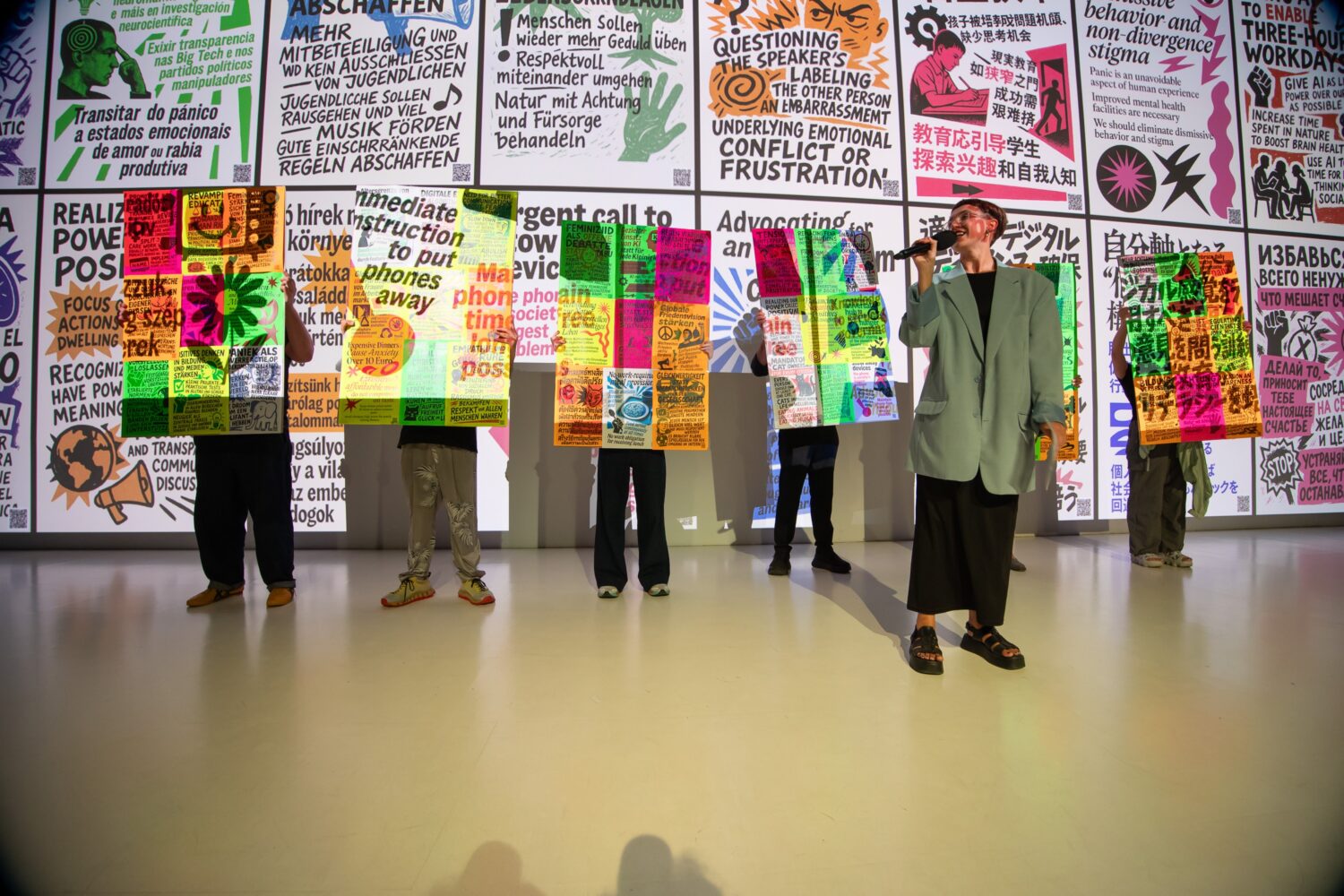

Another example of democratic media literacy is the Citizen Manifesto by Ars Electronica Futurelab. Here, visitors are invited to formulate their personal visions of the future and social aspirations – supported by generative AI. The machine transforms their answers into visual manifestos that can be printed on site or shared online. This creates a collective dialogue, co-designed by AI, about how we want to live. The project shows that digital literacy today means more than just understanding technology—it is the ability to use AI creatively, critically, and collaboratively for social participation. “The process demonstrates how generative AI can support open communication and societal discourse while making the creation journey transparent—from conversation to poster.”

Reclaiming Truth — AI as a Tool for Finding the Truth

“Generative AI is both blessing and curse.“

Paper „Blessing or Curse?“ (Loth et al., 2024)

What we teach shapes our beliefs and, consequently, how we defend the truth in the future. Armed with the right tools to combat disinformation, there is hope for collective truth. It is as if we could turn the tide and reclaim our view of reality. The paradox is that, as discussed in the chapter ‘The Human Loop’, AI could protect truth rather than destroy it.

Technological approaches to ensuring authenticity are already emerging, whether in the form of blockchain certificates, digital signatures or watermarks for journalistic content. However, these approaches fall short if we only combat the supply side, i.e. the production of fakes. The demand side is just as crucial, as it encompasses our human need for validation, belonging and emotional resonance. The Bulletin magazine sums it up: ‘Combatting misinformation means designing friction into share buttons and human psyches.’

Perhaps truth has always been more of a state than an attitude, arising from the interplay of observation, reflection, and verification. Artistic projects, ranging from data visualisations to performative installations, reveal how our perception of truth is influenced by culture and technology. In this sense, art becomes a laboratory for social truth-finding, providing a space in which we can learn to engage with uncertainty in a productive way.

Despite all caution and justified pessimism, the future ultimately lies in our hands, as it always has. AI is a tool, not destiny. Perhaps its greatest strength lies precisely where it can also be most dangerous: in the search for truth itself. If used correctly, AI could help us recognise fakes, expose patterns and sharpen our view of reality. Ultimately, however, the question of truth transcends technology and philosophy; it is the foundation of our society and essential for the continued existence and functioning of our democracy.