Jurij Krpan from Kersnikova Institute talks to Johanna Lenhart from Ars Electronica about how hierarchical our interactions with humans and non-humans are in technology, society, and education, and how these hierarchies can be dissolved into more horizontal, less anthropocentric approaches.

Kersnikova Institute is a non-profit and non-governmental cultural organization that serves as an institutional frame for four venues: Kapelica Gallery, a world-renowned platform for contemporary investigative arts, the hackerspace Rampa, which is a lab for mechatronics, the inspirational laboratory BioTehna, which focuses on the artistic research of living systems, and Vivarium, a lab for bionics where the activities of the other two labs are merging.

What is the mission of Kersnikova?

From the very beginning, Kersnikova’s mission was to bring to Ljubljana the most fascinating works of art that deal with existence, ontologically speaking, but observed through today’s conditions and in the near future. Since the early nineties, with the development of the Internet, with the development of personal computing, ICT, everyone became connected, and we were confronted with how disruptive embracing technology can be. Hosting artists who were working with different technological and scientific discoveries, allowed us to approach technology, not just as users, but as informed individuals, where technologies were just tools that allowed artists and creatives to express themselves.

But from the beginning, access to technology was expensive and limited. The role of the Kapelica Gallery was to facilitate access to artists, to contemporary technologies, and to necessary knowledge, by connecting them with scientists, engineers, and other institutions. The gallery became a place where people could come and discuss their interests. We started commissioning works and developing them together with artists – and as the works became more and more demanding, we had to bring in engineers from the outside, scientists, and other collaborators. To be completely independent, we eventually decided to build our own technological platforms. Now we have a biotechnology lab, a mechatronics lab, and to merge the two, a bionics lab.

I read that Kersnikova originally originated from a student organization?

Yes, that is an interesting detail. During socialism, students were a quite privileged class in society. They were very powerful, and their voices were widely heard. They were financed by taxes derived from their student-side jobs, and that money went into social welfare, recreation, student exchange, and culture. That was a very interesting moment, because in culture, for example, you have these cultural elites who decide who gets funded, who gets the space, who gets presented, and so on. And suddenly, the student organization was able to support different artists, and different projects. This happened vastly in the seventies and eighties. I worked with the student organization as an architect, organizing exhibitions, and eventually they asked me to run what was until then a multipurpose space – Kapelica – as a gallery.

For us, the term democracy is an abstraction of the idea that you have to consider freedom of others as well.

Research at Kersnikova is driven by experimentation, curiosity and investigation. It also looks at the connectedness of nature and technology.

Technology as such is inspired by nature. In most cases it is the reverse engineering of nature. At some point we understood how damaging the use of technology can be – in terms of resources, energy and so on. Now, the fascination with technology is still there, but we are starting to draw more and more inspiration from nature itself. Recently, with biotechnologies, with the development of bio-media and scientific protocols, working with life science has become more accessible. So, it was natural that we started to incorporate more and more of these biological inspirations into our program. But instead of using science to build the devices for profit, we establish situations where plants, animals and other non-human living beings are invited to collaborate. For example, artificial intelligence: if it is used by humans, it will damage nature even more. Where we see the opportunity for the future is when artificial intelligence is not used by humans, but by plants and animals and other organisms. We are trying to create a situation where non-humans can emancipate themselves from the biased human perspective.

And how does this fit in with the Critical ChangeLab?

The Critical ChangeLab is dedicated to investigating democracy and democratic processes. For us, the term democracy is an abstraction of the idea that you have to consider freedom of others as well. We want to try to rethink the anthropocentric approach by trying to understand the connections between technology, humans, and non-humans, in order to dissolve the hierarchical pyramid that puts humans at the top into something more horizontal, more rhizomatic – and this is, where democracy comes in.

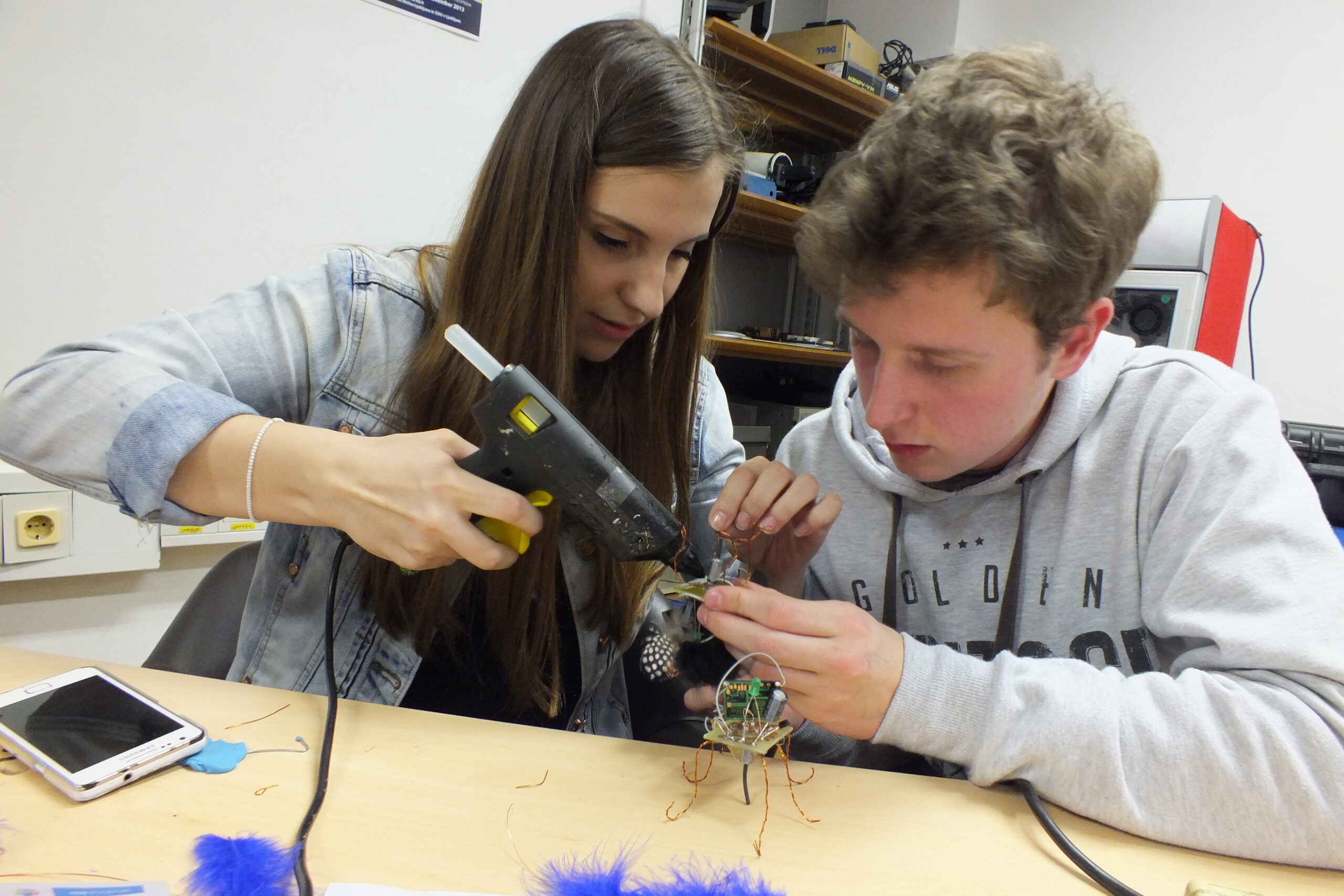

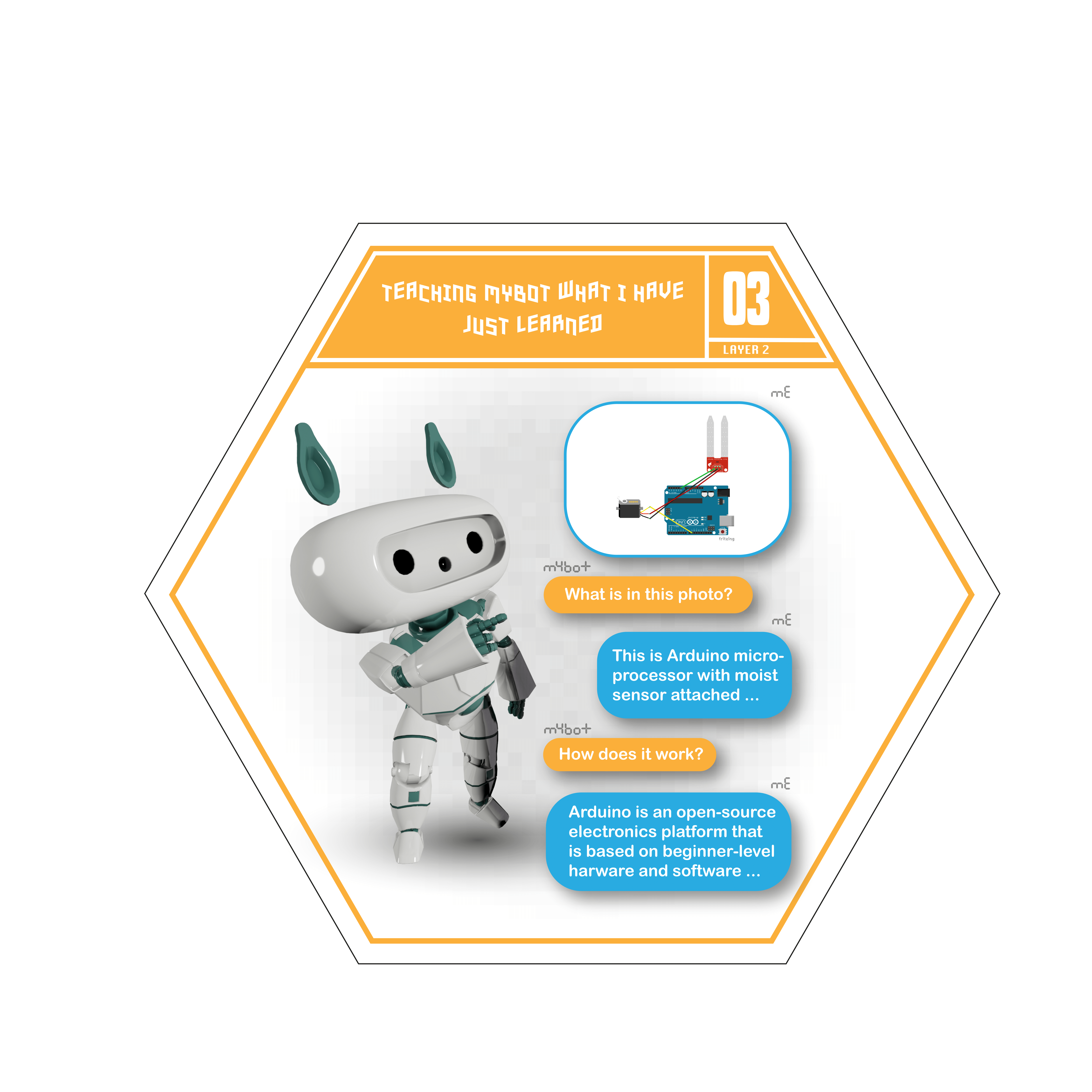

The same goes for education: The processes of education today are very much top-down, cloning existing knowledge to kids, to pupils, to students, and so on. Recently, we started to explore ways in which educational processes in our institution, such as workshops with children, adolescents, young adults, adults, and so on, are no longer led from one tutor to participants, but from peer to peer so that knowledge is transferred horizontally. First, we adopted an approach by Jacques Rancière, who developed an approach described in a book called The Ignorant Schoolmaster, where students learn how to learn by themselves and how to help each other. And now we are building a digital platform, an application, that will be an intermediary between learn to achieve their intellectual emancipation from top down knowlege cloning. But we are not going to use it as a learning tool, we are going to use it as a sharing tool. Knowledge can only be alive if it is shared – we share and we care. That is very important here.

We designed this platform as a game, so kids want to engage in the process. With a custom-built artificial intelligence, users build their own personal assistant – you go through the design phases, etc., and in the end, you understand how AI is built without the top-down knowledge input. What we are developing in the Critical ChangeLab, however, is the soft part, so to speak. We have to develop this peer-to-peer knowledge transfer. In the first phase, we are working with mentors to make them understand that top-down knowledge transfer is not the way to go, and we are developing together how to encourage the kids to play this game. In the second phase, we will have them test peer-to-peer learning. And that will be our zero generation. And then in the third phase, we will observe how these kids share knowledge, how these kids actually play the game – not just at Kersnikova, it will be an open platform so everybody can use it.

Working with others means learning to build bridges.

What are you most looking forward to in the Critical ChangeLab?

Working with others means learning to build bridges. We don’t want to replace the school system, because it’s been doing its job for 4000 years. With our approach we are trying to give a hand, we are trying to build a bridge. Once our system of horizontal learning works, we can work really well with the traditional system, because what kids learn in school can also be applied to this gaming platform that will emancipate them in the real world. So that’s what I’m looking for with the Critical ChangeLab, to figure out how to build a bridge between our experience and the traditional approach to education.

In 1995, Jurij Krpan conceived the Kapelica Gallery – Gallery for Contemporary Investigative Art as a non-governmental and non-profit organisation. Since then, he has been its senior curator. As a curator and commissioner, he has contributed to both national and international exhibitions and festivals, the largest international productions to date being the organization and artistic leadership of the Slovenian national pavilion at the 50th Venice Biennale in 2003, the conceptual gallery Cosinus BRX at the European Commission building in Brussels, and the 5th Triennial of Contemporary Investigative Arts 2006 at the Museum of Modern Art – Ljubljana. In September 2008 he curated the presentation of the Kapelica Gallery in the Featured Art Scene section of Ars Electronica in Linz and in 2009 the survey of contemporary investigative art relating to 80 years of avant-garde art in Slovenia. In 2014 he co-curated the Designing Life section of the Ljubljana Design Biennale and was co-curator of the Slovenian Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale. He has been a member of the Prix Ars Electronica jury for the Hybrid Arts category in 2010, ’13, ’15, ’16, ’17 and 2023. Since 2012, he has been the artistic director of the Kesnikova Institute. Since early 2017 he works on systemic solutions for innovation design, bringing artistic ideations as innovation catalysts in innovation process for smart industries and communities for more sustainable, safer, inclusive and ethical future. In 2020, he co-curated the symposium The Future of Living with AI for EUNIC at Bozar Brussels, where the selection of Slovenian artists was presented in the framework of the S+T+ARTS awards. In 2019, the Government Office for Development and European Cohesion Policy awarded him the title of Ambassador of smart specialisation of the Republic of Slovenia. He is a member of the National Council of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia from 2019 to date. Jurij Krpan gives lectures on the artistic profile of the Kapelica Gallery as well as on the cultural profile of the Kersnikova Institute both in Slovenia and abroad.

With a background in German philology and comparative literature, Johanna Lenhart taught as OEAD lecturer at universities in Egypt and the Czech Republic before joining Ars Electronica in 2023. Her teaching and research focus on narrative practices in different media and contexts, with a passion for how storytelling shapes our past, present and future. Johanna is also a member of the editorial team of the journal medienimpulse. Beiträge zur Medienpädagogik.