Honorary Mention

playablecity.com/projects/playable-city-sandbox-how-not-to

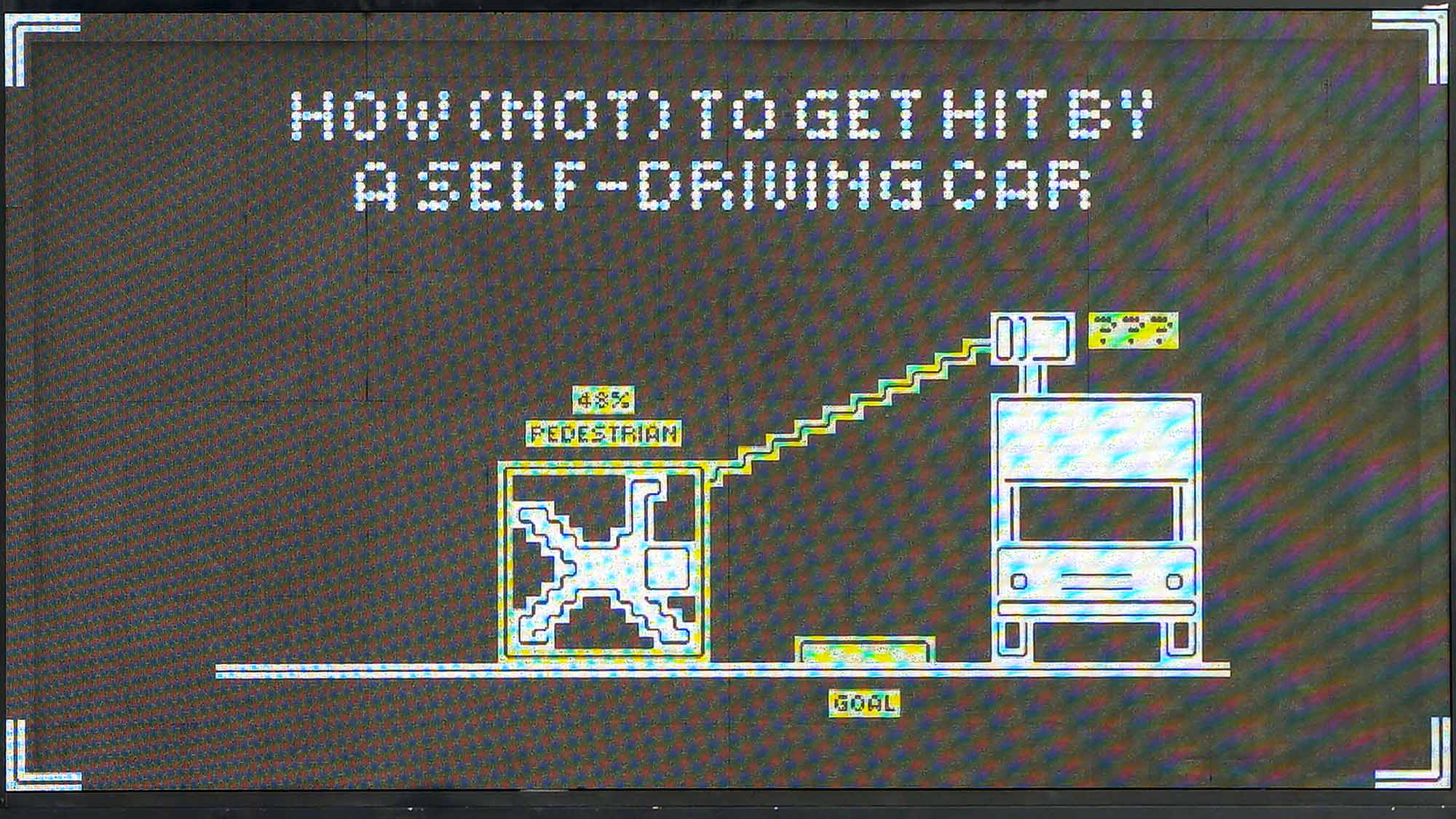

How (not) to get hit by a self-driving car is a game installation that challenges people to cross the street without being detected by an AI. In the experience, players see themselves augmented on a large screen at the end of a playing field, simulating the perspective of an AI-powered camera of a self-driving car. Marking each player is a percentage indicating the confidence at which the system sees them as a pedestrian, and if exceeded beyond a certain limit, the player will lose. So to win, players must figure out how to cleverly disguise themselves to reach the goal without being detected. Successfully winning the game underscores a chilling possibility: in a real-world scenario, such invisibility to a similar self-driving AI system could result in a tragic collision.

Each player’s win generates edge case data that exposes the inability of the algorithm to detect all walks of life, highlighting the hidden biases and flaws embedded in these systems. For example, failing to detect small children or wheelchair users. However, it is up to the players to decide whether to use the data to train the AI or not. Upon victory, players are given the choice to either opt-in their anonymized gameplay footage to improve the AI models, or immediately delete the data. This poses the question of whether people are willing to trade their data for potentially safer autonomous driving technologies, or if they would rather remain invisible, despite the implied risks of inaccurate systems in the future.

The game highlights the problem of geographical bias in AI data collection, where most of the data originates from specific locations, particularly California. This limited approach fails to capture the diverse dynamics of urban settings, for example, how a child plays on the streets of Tokyo. To tackle this issue, the project is making efforts to engage a wider range of global demographics by organizing exhibitions from the UK to Japan, with the goal of attracting a broader audience.

Credits

Music: Plot Generica

Support: Saki Maruyama (Playfool)

Photography: Luke O’Donovan, Playable City Bristol July 2023; Daniel Coppen

Videography:

Jon Aitken, Playable City Bristol July 2023

Jack Offord, Playable City Bristol July 2023

Jacob Gibbins, Playable City Bristol July 2023

Daniel Coppen, Playfool

Commissioned by: Playable City Sandbox 2023 supported by MyWorld

Biographies

Tomo Kihara (JP) is an artist developing experimental games and public installations that draw out unexplored questions from people through play. He has worked on projects focusing on the social impact of AI with institutions such as Waag Futurelab in Amsterdam and the Mozilla Foundation in the USA. His recent works have been exhibited at the Victoria & Albert Museum (London, 2022) and the Asian Art Museum (San Francisco, 2024).

Daniel Coppen (GB) is an artist and designer exploring the nature of relationships between society and technology through the medium of play. Operating as Playfool, together with his partner Saki Maruyama, their practice comprises objects, installations, and multimedia productions, which emphasize play’s experimental, reflective and intimate qualities. Their works have been exhibited at the V&A Museum (London, 2023) and the MAK (Vienna, 2019).

Jury Statement

The ever-accelerating development of AI and the expansion of its services are making our lives more convenient. However, they also make the use of data and technology in our society and culture invisible to us. How (not) to get hit by a self-driving car makes the vision system in cars visible, and even reveals the way the vision system’s data is trained and generated. Designed as a game, it is accessible to small children and wheelchair users, and reveals how this AI model is not always able to differentiate between its players. It also offers a wide range of users the opportunity to teach the AI model as well. The exhibition of this project at various venues will offer opportunities for new collaborations between ‘citizens to improve their literacy where AI has become ubiquitous’ and ‘AI models to learn diversity in the world.’ And, in turn, this could be a catalyst that inspires citizens to propose and establish the rules of digital rights in AI for the future.