In the science-fiction classic „Fantastic Voyage”, a submarine is navigating through the bloodveins of a human body to free the hero from a bloodclot. This utopia of 1966 is still moving humanity in an artistic way. In the course of their application for the SPARKS residenecy at the Ars Electronica Futurelab, Lea and Jakob Illera bridge the gap between science fiction and a palpable scenario by developing the idea of nano-robots, so-called BeBots which have an impact on the gusto for unhealthy nourishment. How they tackled this highly charged topic – also in the limelight of counter interests from the food industry but also in the wake of a potential manipulation of character – they unfolded during an interview at the Ars Electronica Center’s Biolab.

Lea und Jakob Illera present a scribble of their project in the Biolab of the Ars Electronica Center. Credit: Michael Mayr

How did you come up with the idea of so artistically spinning off the “wearable” concept that, as a nanorobot—or, actually, in the form of countless nanorobots—carries out its mission imperceptibly inside the human body? Did this rather combative healing method already occur to you prior to the SPARKS call for entries or not until afterwards?

Jakob Illera: During a radio interview two years ago, I was asked to describe how I imagine the future—for instance, with regard to computerization—and my answer was that we probably wouldn’t be schlepping devices around with us anymore since, after all, everything’s getting smaller and smaller. And the logical consequence in the medical field is a mode of treatment that’s no longer delivered externally.

Lea Illera: I’ve always been fascinated by cyborgs and conceptions of how human beings and machines will someday interact and, of course, how it feels to have technology inside your body. On the other hand, I’m also interested in the question of what it would mean for society if there were technically “enhanced” human beings. Who can afford that, and who has to do without? What I like about our take on the “Responsible Research & Innovation” topic is, in addition to the science fiction approach, considering it from the perspective of a scholar in the humanities or social sciences. But the concrete idea of nanorobots emerged from the SPARKS call for submissions. We wanted to design a wearable that’s as realistic as possible, one that inherently entails an ethical discussion, one that engenders a certain degree of tension. And this concept achieved that, alone due to the fact that it’s situated inside the body and not worn on it.

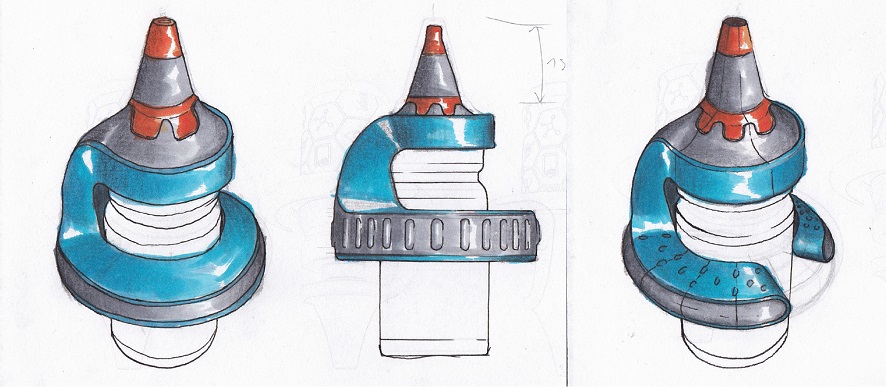

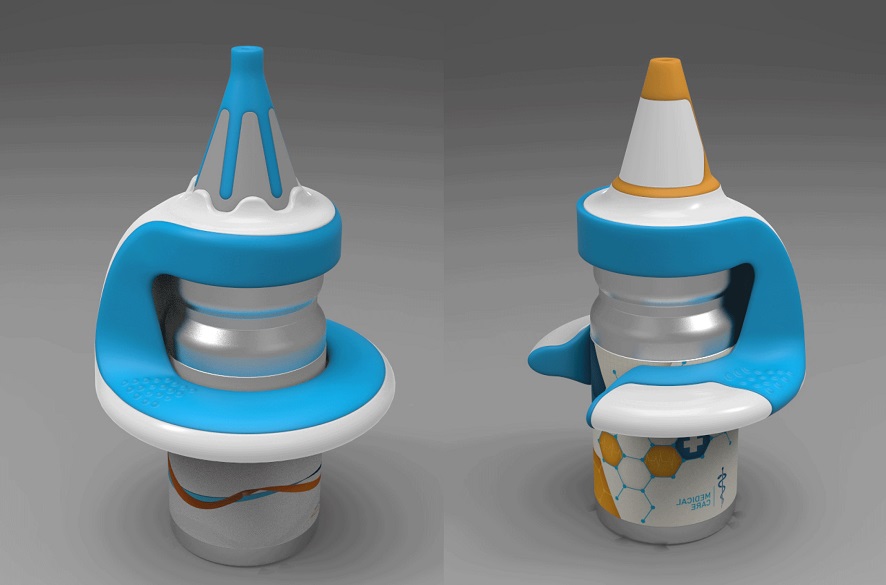

Drawings of the futuristic inhaler….

… and the 3D-models of them. Credit: Christian Kittner

When you consider classic science fiction film motifs, then you conclude that most carriers of substances floating around in the blood are agents of misfortune or victims of their role as transporters. So, isn’t it simply inevitable that people are skeptical of such high-tech agents?

Lea Illera: Your perception is based predominantly on the American style of sci-fi filmmaking. I’m a big fan of the Japanese variety like “Ghost in the Shell,” in which the medium transporting a messenger substance in the blood is portrayed as something positive. The human-machine connection is a part of the Japanese culture and aesthetic. Depending on your point of view, you can extol technology or demonize it, and this is very clearly demonstrated by discussions surrounding how people use their smartphones.

But isn’t it necessary to protect people from themselves, especially when it’s a matter of such an explosive nature: a material modification and thus changing the very nature of a human being?

Lea Illera: Prohibiting, on those grounds, something that’s potentially beneficial to humankind can’t be the solution. Ultimately, you can threaten people with all possible consequences. But if we follow this line of thinking that focuses on security and hinders progress and take it to its conclusion, then humankind will be paralyzed by fear. You have to have ultimate trust that this can be regulated by societal mechanisms.

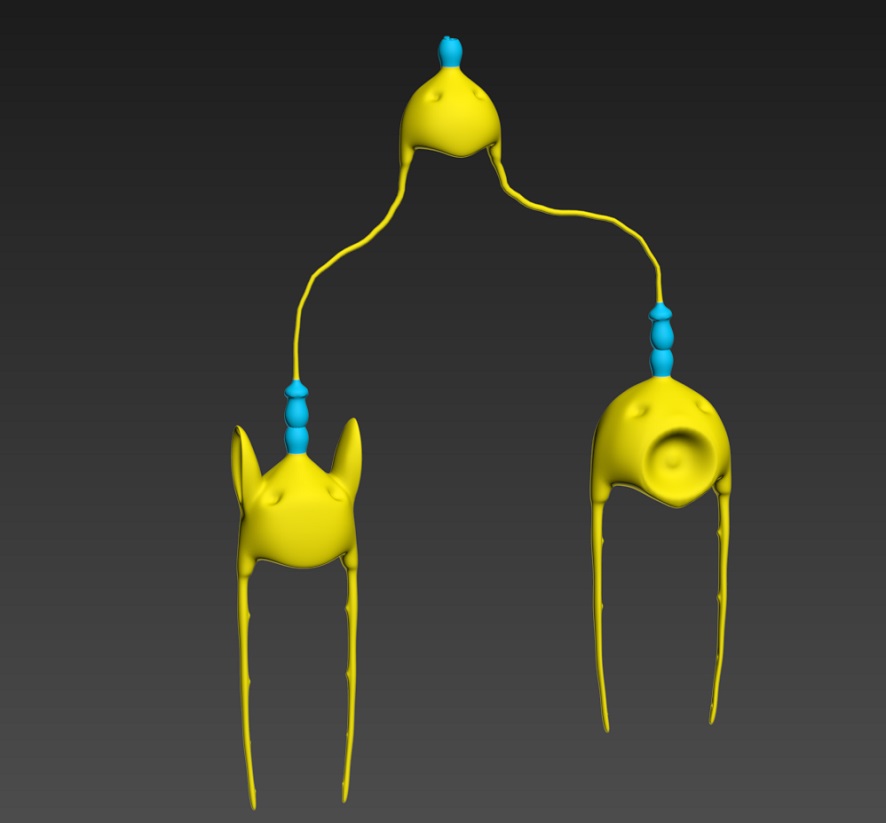

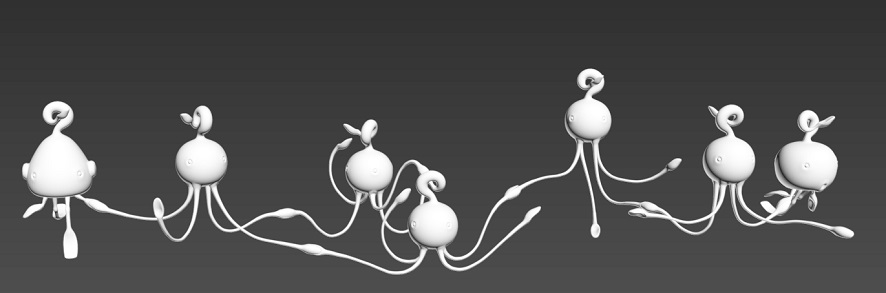

The child-suitable design of BeBots should mitigate the scepsis of intake. Credit: Werner Pötzelberger

But if you take the core idea of this medical innovation as far as it will go, then the ultimate aim of this research is humankind’s age-old dream of eternal life, or is this taking it a bit too far?

Jakob Illera: Every type of medical innovation that, like the one we’ve conceived, has far-reaching consequences potentially lengthens human life. But that’s not the primary objective. What we want is to improve the attitude towards life of those people who don’t succeed in carrying around less weight with them. The aim is healthier nutrition. The intervention occurs in the moment at which we make a decision in favor of more nutritious food and against foodstuffs that make us sick. What we’re juxtaposing to the aspect of abuse is that the medication can only be dispensed by a pharmacist—which, of course, doesn’t prevent people from obtaining substances illegally.

Here, an entire industry will be launching attacks against your product since it tends to thwart their aim of profit maximization by the use of potentially unhealthy ingredients or their means of production at the cost of sustainability.

Jakob Illera: We’re already familiar with this from the attempt to introduce a traffic-light system. Nevertheless, tagging a product by sticking a label on it is eliminated in our system. It’s rather the opposite—the BeBots would function like an adblocker so that I don’t even see the food industry’s enticements. But it’s obvious that hamburger chains and other big players in the food industry would sue to prevent this.

Based losely on Lucas Cranach the Elder: BeBots would have taken the temptation back to its original perspective. Credit: Lea & Jakob Illera

When you consider how Europe reacts to genetically engineered corn, you realize that it’s hard to achieve general acceptance in any case, since people mostly just internalize the simplistic message that this is another case of intervention in nature.

Jakob Illera: Obesity is a global problem that has direct as well as indirect effects on the human body and on society as a whole. This year, the ratio of underweight to overweight people has shifted in the direction of overweight for the first time.

Lea Illera: Just like social changes such as these proceed slowly, the introduction of nanotechnology in medicine is also a gradual proliferation process. This means that if BeBots would come onto the market, the level of acceptance would be totally different. Here, we’re talking about a period of 10 years. Just think about how the acceptance of inoculations has changed over time.

Work in progress – the diffuser of the inhaler in the making. Credit: Lea & Jakob Illera

Speaking of marketing aspects … how would you market this product?

Lea Illera: We didn’t pay as much attention to marketing as we did to coming up with a prescription medication that a physician prescribes not only to get patients to lose weight but also in cases of food intolerance. You have to help such patients overcome their fear of ingesting the medication. We resolved this issue in the form of a spray that works like a nasal decongestant you use when you have a cold, so it’s an inhaler that people are already acquainted with. The widespread familiarity with this common, everyday product is designed to reduce reservations to a minimum. Moreover, we’re not forcing anybody into anything—those who want to continue to eat burgers would refuse to take this medication, but those who’ve been unhappy and psychologically impaired for years ought to get an opportunity to lead a better life. The whole thing is done on a voluntary basis.

When you consider that there are millions of these particles transporting messenger substances in the bloodstream, the question that arises is: How do they exit the circulatory system?

Lea Illera: The materials are our own DNA, so we’re not ingesting any foreign bodies. It’s important to communicate that too. As soon as they stop working, they’re neutralized. The substance is metabolized. You don’t have to be admitted to the hospital, there are no sutures involved and, ideally, no side effects and allergies. The only “negative aspect” is purely conceptual—we influence wishes!

Prototypes of BeBots and inhalers. Credit: Michael Mayr

The fact that this is an art project that’s going on display as part of an exhibition brings me to the decisive question: What are you actually exhibiting?

Jakob Illera: We show the product packaging, of course—which is to say, the inhaler—the product’s effect in the form of a pictochart, and the whole thing is broken down as much as possible in a very simple way, one that just about any child could comprehend. More detailed and comprehensive content is available on our website. As for the inhaler itself, this is my bread-and-butter since I’m a product designer in everyday life. But the rest of it is pretty much uncharted territory.

Lea Illera: Another high priority for us is to show the enlarged nanobots as something “cute,” and in doing so we’re carrying on something of a tradition—consider, if you will, flu viruses depicted as soft toys. This has been done already. Or what about a pharmacy magazine that explains the human body to children in a playful way? After all, we need an approach that keeps abstraction to a minimum, because you don’t conceive of what this is as being a robot. I mean, you don’t see it at all. The nanobots are our helpers that can reach places that are inaccessible to human beings.