Christopher Columbus wanted to sail to India and ended up discovering America. Louis Pasteur forgot about a piece of labware containing pathogens; much later than planned, he nevertheless administered them to his chickens and discovered the phenomenon of immunization. And Mas Subramanian and his team actually wanted to test the magnetic and electric properties of manganese oxide, but instead stumbled upon a previously unknown pigment, YInMn Blue.

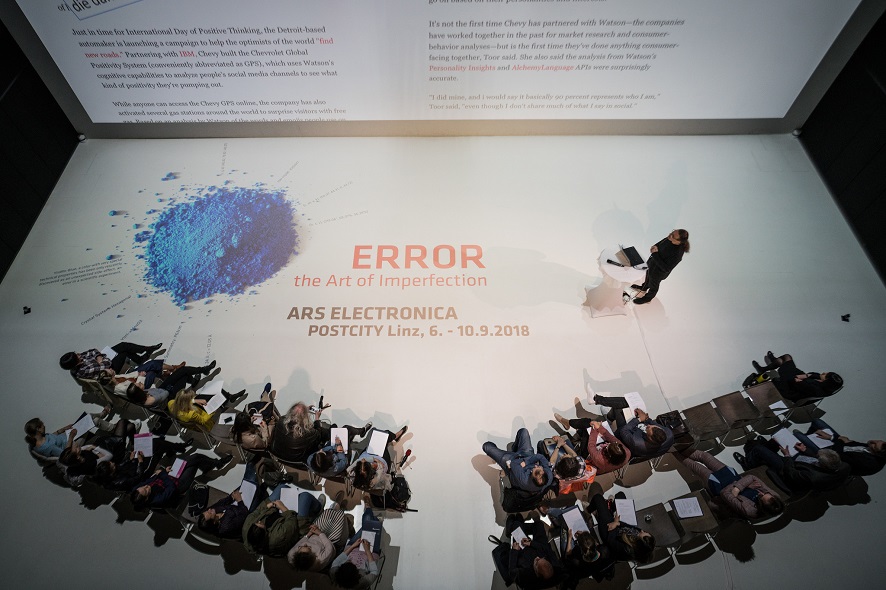

And it’s precisely this shade of blue that adorns the posters announcing this year’s Ars Electronica Festival and its “Error – The Art of Imperfection” theme. September 6-10, 2018, the focus will be on mistakes, fails, blunders and deviations from the norm. Whether celebrated as a marvelous source of innovation or scorned as the cause of catastrophic accidents, error is the center of attention this year.

How can an error become a driving force behind a positive development? What approach do we have to take to enable us to move forward despite failure—or even precisely as a result of it? And how human is it to err, actually? We interviewed Gerfried Stocker, artistic director of Ars Electronica, to find out about this year’s festival theme.

Gerfried Stocker, artistic director at Ars Electronica. Credit: Martin Hieslmair

Last year’s festival, entitled Artificial Intelligence – The Other I, was such a resounding success. So how do you follow an act like that?

Gerfried Stocker: It’s always a challenge to follow up on a successful festival. And in the case of Artificial Intelligence, there’s the added fact that the theme has incredible dynamism. During the preparations as well as in our follow-up discussions, we realized that this topic is not only technologically and scientifically relevant; it really gets to people emotionally. Thus, we came to the conclusion that we couldn’t just shift to a completely different theme; rather, we asked ourselves how and where we can follow up on this. Then, the key formula for us was the step from artificial intelligence to social intelligence. And that takes us more strongly into the area that’s actually Ars Electronica’s strong suit—where technological developments have social and cultural consequences. And there’s probably no other field in which those impacts are so powerful and explosive as they are in artificial intelligence.

What makes the Error theme so relevant right now?

Gerfried Stocker: A variety of reasons. You can deduce this in very simple, almost banal terms by considering the current mood of the public and public opinion. There prevails a strong impression that something has gone awry with the 21st century and our dream of the Digital Revolution and an open digital society. Millions of people have reason to feel threatened. They are concerned about their sovereignty over their data and their private sphere. Furthermore, we see ourselves as being confronted to an unprecedented extent by counterfeiting, deceptions, fakery and populism that transcends all national borders and influences public opinion formation and political decision-making. Moreover, many people feel a diffuse anxiety at being left behind by the speeding dynamics of technological development. Are robots taking our jobs? Is AI assuming control over our society? So this already raises the question of how are we to rescue the original dream of a digital world. Can any of it even be saved? What do we want to save? Or, as this is often formulated at the moment: How to fix the future. How can we get our society back on the right track and moving in a direction that we deem good and proper?

Here, we’re confronted by a wonderful double meaning of the term error. What error have we been victimized by? What’s the cause of this undesirable development? And aren’t an often-cited “error culture” and a greater readiness to take risks what we so desperately need? Both of them constitute the precondition for even being able to conceive of and implement other solutions and new approaches. And precisely this is what’s so fascinating about dealing with the subject of errors. After all, an error isn’t a mistake but rather a deviation from our expectations. Error is the disappointment, but it’s also the latitude, the leeway that arises when we permit ourselves to deviate from the norm, when we allow ourselves to call ourselves into question. Then again, who actually defines our norms? On what basis are certain conceptions or parameters simply accepted as dictates? And how can we institute those free spaces in our society that we need to think new ideas? This is a very decisive point at which art meets technology.

Credit: Robert Bauernhansl

Thus, error is deviation from the norm. How is this manifested on the social level?

Gerfried Stocker: There’s a lovely analogy. Error and tolerance are twins, siblings. Tolerance is necessary for error’s productive power to unfold. The question of exactly which socially productive forces a deviation runs up against can be visualized in very simple, banal terms by considering just how many errors and dead ends nature needed for the transition from the very first bacteria millions of years ago to Homo sapiens! And how many errors and mistakes has it taken for us to learn from—we as individuals and humankind as a whole over the 200,000 or 300,000 year that Homo sapiens has existed—in order to attain our current state of development? The final question is how much experience and knowledge would have missed out on if there had not been periodic deviations—the Others, people with alternative ideas and different beliefs. When you look at this from a higher perspective, you realize that all the human beings and ways of seeing things that are so easy to reject have often been precisely those wonderful, and ultimately highly praised, sources of innovations, of trailblazing ideas, of fantastic inventions, and, in the final analysis, of that what we consider to be social progress.

Credit: Robert Bauernhansl

But, at the same time, there’s a reason why humankind strives for perfection.

Gerfried Stocker: I believe you have to look at the two sides of this story. One is the very human, philosophical dimension: Why aren’t we satisfied with what we are? Why this incessant search for improvement, striving for perfection to the point at which we can say that human imperfection is transcended into a form of divinity to which we impute perfection—the ultimate, so to speak. And, of course, there’s the question of the driving forces that arise from this striving for perfection.

The other side is a very rational one—the economic, technological domain that has to do with optimization, establishing norms, improvement and raising productivity. It’s fascinating that we as a society have begun to interconnect these two questions—the transcendental, philosophical issues, and the concrete, everyday matters of optimization in business and technology. There’s this pithy saying that philosophy since Nietzsche has abolished god. Now, with technology, we’re endeavoring to create a new one. And precisely this discussion of artificial intelligence has an incredibly spiritual character.

It is undoubtedly highly significant that we human beings always strive for perfection. It’s a profoundly philosophical question, one that will also be of essential importance at the festival. Why are people compelled to achieve perfection? Why do we believe that we are insufficient the way we are? How important has this been heretofore and how important will it remain for our further development? Calling the status quo into question is probably one of the greatest driving forces for development, regardless of which field you consider. On the second level too, where this is a matter of commercial and technological interrelationships, this is a very concrete matter—a blunder in the chain of production or an error means major financial damages and might even trigger a chain reaction of negative consequences. This means that we need a mode of dealing with errors that emphasizes anticipatory behavior. I believe that the ability to assess the risks that technology and science entail still isn’t particularly well developed in our society.

At the festival, it will be interesting for us to consider these two levels comparatively. What is the metaphysical dimension of the striving for perfection? And what are the concrete, everyday demands of this? And that, in turn, raises a further question: What are we missing out on while we’re complying with the dictates of optimization, efficiency and increased productivity? Standardization is always automatically a process of narrowing down to that which we’re already familiar with. But our aspirations actually go way beyond this. This incredibly lovely ambivalence says a great deal about how we function as human beings and as a society.

So, is the festival critiquing the currently prevailing obsession with optimization?

Gerfried Stocker: I believe this has to be criticized in every respect, not least of all because it’s not productive in and of itself. We have to realize that many changes have pervaded our world to a massive extent in a very short time. The dynamics of the Digital Revolution have triggered so many developments on all levels, which we have to begin to address. And when the world around us changes, then the strategies and approaches we utilize to come to terms with these changes have to change along with it. We have to be flexible and capable of adapting; otherwise, we’ll just be at the mercy of all these developments. We will always remain just objects and never reach the position we strive for—namely, a subject, one that controls, steers and designs our circumstances.

Credit: Robert Bauernhansl

Innovation doesn’t come about by conforming to the norm. The theory of creative destruction says that new things come about only when existing ones are destroyed. As a rule, this happens intentionally—but if so, can this even be said to be a matter of an error?

Gerfried Stocker: One of the fascinating aspects of this topic is that, although these terms are actually quite clearly defined linguistically, the way we deal with them in everyday life vacillates widely, ranging from error all the way to deception. The point of departure of our considerations was to define error as an interesting middle point between failure on one hand and fake on the other. Maybe you have to say, in an almost naïve way, error is also the myth of innocent experimentation. This is a myth we’re familiar from the history of culture—the innocent fool capable of summoning forth a turning point in a narrative, advancing the story’s plot or saving humanity. This is a euphemistic vision, but also one that we require. We need to generate enthusiasm that we are indeed capable of achieving a breakout. And even if there’s not a consummate strategy worked out to the last detail, there’s still the ultimate hope that one could emerge by coincidence, as the result of an error, unexpectedly. When you look back on the past, the history of humankind’s development, all the technologies and civilizations, you see that this element of chance has repeatedly played a major role. The question is how we can bring this phenomenon to bear. How can we better prepare ourselves for it? In our discussions, a formulation that often came up was that error is actually a strategy of resilience in order to assure that developmental latitude can even come about amidst these hurtling dynamics.

The festival theme’s subtitle is The Art of Imperfection. Should error be elevated to an artform?

Gerfried Stocker: I believe we have to do precisely that at present because we live at a time in which we’re discussing what technology is doing to us human beings. Consider, for example, the debates surrounding robotics and AI. No sooner do you begin addressing one of these technological concepts than a whole story about this questions starts to develop. We can hardly avoid this juxtaposition—technology on one hand, perfect, better than human beings; and, on the other hand, us, imperfect, and accordingly in the process of getting left behind. This configuration can be countered only by a bold conception or manifesto that calls for celebrating this imperfection nevertheless. After all, this is the essence of being human and perhaps it’s the only thing that, over the long term, will differentiate us from machines. If, in the human-technology interrelationship, imperfection is a uniquely human feature, then we should make a strength out of it. This isn’t a matter of setting up something in opposition to enthusiasm for technology, but rather of pairing it with something that helps us to advance this development in a positive way. We’re not looking to counter enthusiasm for AI with a call for social intelligence; we want to place them side-by-side. It’s a matter of play and a bit of provocation. Actually, we have to postulate imperfection as something great, quintessentially human, and perhaps even a principle of nature in order to stay on top.

Isn’t it a great hindrance that error often triggers tremendous fear on the part of human beings?

Gerfried Stocker: Sure, but errors are a source of fear because we consider them to always be irreversible. If we come to a more open, more flexible form of understanding development, then it makes absolutely no sense to believe that tremendous effort will enable us to eliminate all eventualities, potential errors and their adverse effects. That means that we’re confronted by a choice: either we take a step forward and prepare for the fact that the terrain we’re about to enter is a bit shaky and our position in it won’t be stable; or we procrastinate, we don’t make a move, we persist at a standstill. We can’t want that—a standstill is always the worst that can happen to us.

We should find a good balance between the courage and enthusiasm to move forward, the acceptance of the fact that every step of the way can’t be 100% successful, and trust that we as human beings are in a position to correct errors. To accomplish this takes some consideration of a culture of dealing with errors. This concept is very hot right now and, for good reason, is very prominent in discussions of the future. Naturally, this is a matter of determining which errors have to be avoided. But this is also a matter of tolerantly dealing with errors. And maybe most important of all is preparation to enable the correction of errors. This is an element of innovation culture, which our society really needs. And this brings us to the capacity to integrate others, people with alternative ideas, into our society. Here, we’re talking about an open society and, thus, one of the central problems of our time—the strongly populist rhetoric of fear that’s currently coming to the fore throughout the world, and has the totally opposite effect. It hems us in; it makes us hesitant and timid; it deprives us of courage. And this, in turn, is precisely what a festival of art and culture has to take a stand on and push back against.

Gerfried Stocker is a media artist and telecommunications engineer. In 1991, he founded x-space, a team formed to carry out interdisciplinary projects, which went on to produce numerous installations and performances featuring elements of interaction, robotics and telecommunications. Since 1995, Gerfried Stocker has been artistic director of Ars Electronica. In 1995-96, he headed the crew of artists and technicians that developed the Ars Electronica Center’s pioneering new exhibition strategies and set up the facility’s in-house R&D department, the Ars Electronica Futurelab. He has been chiefly responsible for conceiving and implementing the series of international exhibitions that Ars Electronica has staged since 2004, and, beginning in 2005, for the planning and thematic repositioning of the new, expanded Ars Electronica Center, which opened its doors in January 2009.

The Ars Electronica Festival is set for September 6-10. The location is POSTCITY Linz. This year’s theme is Error – The Art of Imperfection.

To learn more about the festival, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter and visit our website at https://ars.electronica.art/error/en/.