What’s merely insinuated in discussions about Big Data in our neck of the woods has already become reality in Southeast Asia. Songdo, a city built from scratch on a stretch of South Korean tidal flats, is conceived for sustainability and completely networked—i.e. an object of total surveillance. This development demonstrates how the utopia of a lifestyle ensemble that’s the expression of a complete design concept yields a split verdict. To the minds behind the raum.null artists collective, artificial metropolises like Dubai and the phenomenon of gentrification of city neighborhoods are grim harbingers of a world divested of its naturalness, one in which (species) diversity has to cede primacy to the visions of urban planners.

Blaring Multimedia Rage against the Brave New World

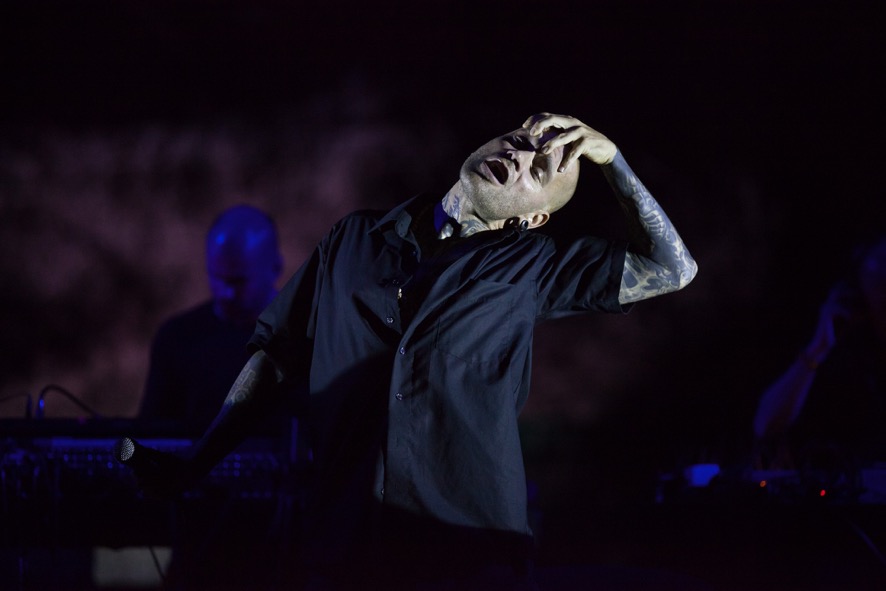

Their conceptual alternative to a bliss-inducing Smart City from the drawing boards of futuristic architects could be experienced by visitors to the former Austrian Postal Service logistics center on opening day of the 2015 Ars Electronica Festival. Following up on their performance entitled “Quadrature,” raum.null staged “The Sixth Wave of Mass Extinction,” a vision of the future in dark tonal hues and disquieting images that leave plenty of room for interpretation among their various levels of abstraction. But despite all the possibilities for free association, the producers of this project are unambiguously out to get a message across: When human beings design habitats at the cost of nature, what they end up engendering are uniformity and monotony. So it’s no wonder that, amidst the droning and murmurs by Chris Bruckmayr and Dobrivoje, the melancholy shines through here and there—like the doubts evoked by a scenario for everyday life that most people find unworthy of striving for or even see as a threat.

To shine a proverbial light into the darkness of their project, Chris Bruckmayr, producer Claudia Schnugg (AT) and two of the visual artists, Veronika Pauser (AT) aka VeroVisual and Peter Holzkorn (AT) aka voidsignal, provided details about staging an encounter with an issue that entails people confronting themselves. (NOTE: raum.null member Dobrivoje and visual artist Florian Berger aka Flockaroo were not present at the time of the interview.)

The title of your project alludes to factors that have already been identified as the triggers of this mass extinction. To what extent does the very process of planning a postcity make humankind complicit in yet another wave of species destruction?

Chris Bruckmayr: The way futuristic cities that beckon contentment are designed gives little if any consideration to the coexistence of people and animals. All thinking is focused on an ecological lifestyle that, of course, is affordable only by the well-to-do. This is manifested by overpriced whole food markets, eco-construction techniques and stickers certifying organic foodstuffs. Flora and fauna are showcased as green oases. In principle, farms are the ideal model of how future cities should look. When we think about configuring our future, we’d do well to plan in zones that permit a certain degree of wildness. Berlin after the fall of the Wall was the site of untamed activity and offered people design freedom. Gentrification has leveled those free spaces for urban creativity. For me, it isn’t a positive utopia to live in a thoroughly designed ecological city in which you suffocate from boredom. We wanted to propagate an acoustic correspondence to this uneasiness.

Was there some source of inspiration that urged you to deal with this issue?

Chris Bruckmayr: The science-fiction film “Blade Runner” superbly portrays an urban dystopia in which, ultimately, human beings flee from themselves. And that’s precisely the direction we’re headed in. There exists, in an artistic sense, a kitschy variant whereby cities are depicted in idealized terms. In reality, the new megacities look totally grungy and the living conditions they provide for human beings are steadily deteriorating. Generally speaking, supercities built from square one according to a master plan and an overall design concept are affordable by only a few wealthy individuals. Just consider Dubai. When you think this through, you see that this wave isn’t just a biological extinction but a mental one too. And where’s this leading? But the question I’ve been wrestling with the most in conjunction with this project is:

“What kind of effect does it have on people when they’re surrounded by the sound of silence, when, even acoustically, nothing foreign reaches their ears? When they hear only the sounds of their own kind and a few pets. Is this state of boredom our destination of choice? Is achieving total control the inevitable objective of our actions?”

So, when you use the term mass extinction, are you referring not only to the extermination of animal species but also to the destruction of a large proportion of humankind by an elite?

Chris Bruckmayr: The performance shouldn’t be understood as a dystopian gloom-and-doom scenario but rather as a warning. That’s why the narrative arc segues from a rather chaotic state to an increasingly uniform, ever-drearier structure. The question is: “Is that what we want?” What interests me is the latent apprehension that many people associate with the 21st century.

Where does this come from?

Chris Bruckmayr: There are many reasons. The changes are proceeding too quickly for some folks. They have the feeling that they’ve lost something from their natural surroundings. Let me make one thing clear: I’m no “idealizer” and I have no objection to civilization. What disturbs me is the human tendency to use everything possible (and impossible) as a projection surface for idealized visions. You find idealization on all sides—for instance, the natural idylls in vacation catalogs. It’s the same with certain neighborhoods that are suddenly IN because they’re featured in a mediatized mise-en-scène.

Credit: Tom Mesic

Is visualizing such urgent sociopolitical issues a core task of artistic work in the 21st century?

Claudia Schnugg: Artists already began to confront sociopolitical issues and come to terms with them in their works in the second half of the 20th century, and this is still very much present in contemporary art. I personally do indeed believe that it’s an essential function of art to deal with today’s pressing sociopolitical questions. Many artists, unfortunately, don’t sufficiently take advantage of their creative resources. Although they utilize various media, artifacts and materials like photos, political correspondence and newspaper articles to call attention to various subjects, their audience is thereby made to approach these works on a highly intellectual level. Or, in the case of works that evoke compassion, by bringing forth empathy. Both strategies are totally legitimate but they don’t completely exhaust either the aesthetic potential or the means of storytelling. These works become truly interesting when they convey their content above all by means of their aesthetics, which can challenge the audience and address several of the senses.

Which means of storytelling do you use in “The Sixth Wave of Mass Extinction”?

Peter: As far as the musical development was concerned, we had a rough outline that the sound artists refined during the weeks leading up to the Festival. We split up the dramatic sequence into several parts, a couple of intermezzi and an intro/outro. In this way, we had a few scenes, each of which corresponded to a mood set by one of the story’s narrative segments. To each of these, we assigned certain keywords—in a few instances, very general ones such as “beautiful and dominant nature”; in other cases, specific ones like “sensory overload / staccato images of cities and urbanization.” For me personally, this is more a matter of creating a general mood; the observer’s experience should be rather an abstract one. Several of the best works in the visual & media art genre abstract their narratives precisely to the extent that they have form and substance but are still open to interpretation.

How did you interact with the music? Do you draw inspiration from the atmosphere, from the beats, or something else entirely?

Veronika: To start out, I listen to musical excerpts, repeatedly and in concentrated fashion, to derive inspiration for my visuals. I decide on various scenes on the basis of the atmosphere as a means of supporting the music and thus advancing the whole story. In going about this, I try to get across a certain mood, and I take my inspiration from the sound but I don’t let it dictate to me. For me, it’s very important to retain the live aspect with the visuals too, which means that not everything is predefined so there’s the possibility of reacting spontaneously. An interactive dialog should emerge between the music and the visuals. To make that happen, I like to combine generative material with pre-produced content or even found footage, and I love to integrate new technologies and tools into my visual performances. Then, during the live performance, I react mainly in manual form to the music by adapting various parameters in the visual software. At some points during the performance, though, it’s also a good idea to do a sound analysis as an additional tool in order to be able to precisely synchronize with the beat of the music.

Credit: Florian Voggeneder

The appearance of Chris’ brother Didi added an additional “dramaturgical element” to the performance. What part does he play in the overall narrative?

Chris Bruckmayr: He was a late addition to the conception. The idea was to stage an appearance of a figure from the philosophy of Plato: the demiurge, a craftsman who’s responsible for the design and maintenance of the physical universe—though he shouldn’t be confused with the Creator. In the performance, he laments the loss of the species that were eradicated by humankind. At the end, he recites a text that Yuri Tanaka translated into Japanese. The English version is a play on the “Tears in Rain” monolog that comes near the end of the film I previously mentioned, “Blade Runner.” Just before he dies, Roy Batty [Rutger Hauer], an android being hunted by chief protagonist Rick Deckard [Harrison Ford], utters his last words: an expression of thanks for having been permitted to see what the human eye sees. We’ve rewritten the monolog for the demiurge and his lost creation.

“I’ve… seen things… you people wouldn’t believe.

I watched gigantic herds on their jolly trip west.

Glittering swarms of birds and insects filling the air with sounds of abstract beauty.

I perceived the call of the fish and the mollusk in the deep sea.

I was awestruck.

All those… moments… will be lost, in time, like tears… in…rain.

Time… to die.“

Credits:

Sound: Chris Bruckmayr & Dobrivoje Milijanovic (raum.null)

Voice: Didi Bruckmayr (AT) aka Fuckhead

Visuals: Veronika Pauser (AT) aka VeroVisual, Peter Holzkorn (AT) aka voidsignal and Florian Berger (AT) aka Flockaroo

Producer: Claudia Schnugg (AT)