The Print3Dfuture Conference, Austria’s first conclave dedicated to three-dimensional printing, was held on March 27th at the Odeon Theater in Vienna. Among the speakers was the manager of the FabLab at the Ars Electronica Center Linz, Alina Sauter, whose speech was entitled “3-D Printing for All.” Now that she’s back in Linz, we’ve had a chance to talk to her about this fascinating topic.

So tell us, Alina: How long have you been involved in 3-D printing?

Alina Sauter: I joined the Ars Electronica Center’s staff in 2008 while I was still studying ceramics at Linz Art University. The school has a very strong New Media program including majors in Interface Cultures and Time-based Media, which means that even if you’re studying something like ceramics, at some point you get exposed to new media. Anyway, I took some courses in 3-D Modeling and AutoCAD, so it was at Linz Art University that I first came into contact with 3-D printing. And after I graduated, I remained on the staff of the Ars Electronica Center, where there’s been a 3-D printer in the FabLab ever since the new facility opened in 2009.

Who’s allowed to use it?

Alina Sauter: At the FabLab, anyone can attend a workshop to learn to design objects using various modeling programs, and then you can print them out three-dimensionally. We even have very user-friendly programs that enable elementary school kids to give free rein to their creativity. Since the 3-D printing process lasts several hours, each object is also generated as a paper model by means of a laser cutter. What makes the Ars Electronica Center’s FabLab so extraordinary is its openness, the fact that anybody can just drop by and use the 3-D printer.

Alina Sauter at the Print3Dfuture Conference in Vienna

At the Print3Dfuture Conference you gave a speech entitled “3-D Printing for All.” Is that the concept being pursued by the FabLab at the Ars Electronica Center?

Alina Sauter: There are FabLabs all over the world, but at most of them the 3-D printer can be used only by specially trained individuals. In those FabLabs, you have to be a member like in a club or a hacker space. The visitors to the Museum of the Future don’t have to join a group. We make 3-D printing available not just to a particular community but rather to everybody. Even those who don’t want to get actively involved themselves are cordially invited to stop by and learn about the technological development of 3-D printing in medical, artistic and social contexts. And needless to say we’re happy to welcome people who are interested in conceiving and designing objects and then printing out the results.

How does 3-D printing work, actually?

Alina Sauter: There are various ways to go about this. You can construct something yourself using a 3-D modeling program, or you can download a model free of charge from a website such as Thingiverse, or you can scan in something that you can later print out three-dimensionally. For example, if you want to repair something: all you have to do is take the part that’s broken, scan it in, repair it using a 3-D modeling program and then print out the brand new part. If your aim is to realize your own idea, then the first step is to prepare a sketch on paper. After that, you model it using a program that’s equipped with the right tools to do the job. Many programs come equipped with toolboxes in which you can select from among an assortment of basic forms. Most of the objects we encounter in everyday life are based on elements such as a sphere, ellipsoid, rectangular solid, cube, cylinder, etc. In 3-D modeling, you usually use a combination of these forms. And once the modeling is done, you can get busy printing.

What material is used for the printout?

Alina Sauter: Our 3-D printer uses plastic. But there are a great many materials being used in this area at the moment. There are printers that print not only with plastic but also with PLA [polylactic acid, a thermoplastic aliphatic polyester derived from renewable resources such as corn starch]. There are also printers that can print metal, polymer plaster or even porcelain. And there are those that use edible materials like sugar. Barilla is currently developing a pasta printer, and NASA is working on a pizza printer.

The advantage of 3-D printing is that it doesn’t matter how many pieces you have to produce or how complicated it is to construct the model, since the basic principle is always the same and there’s no loss of quality. The object is printed out by means of a layer buildup process. This is also the reason why 3-D printing is being used in so many different sectors—for instance, the auto and airplane construction industries, mechanical engineering and medicine.

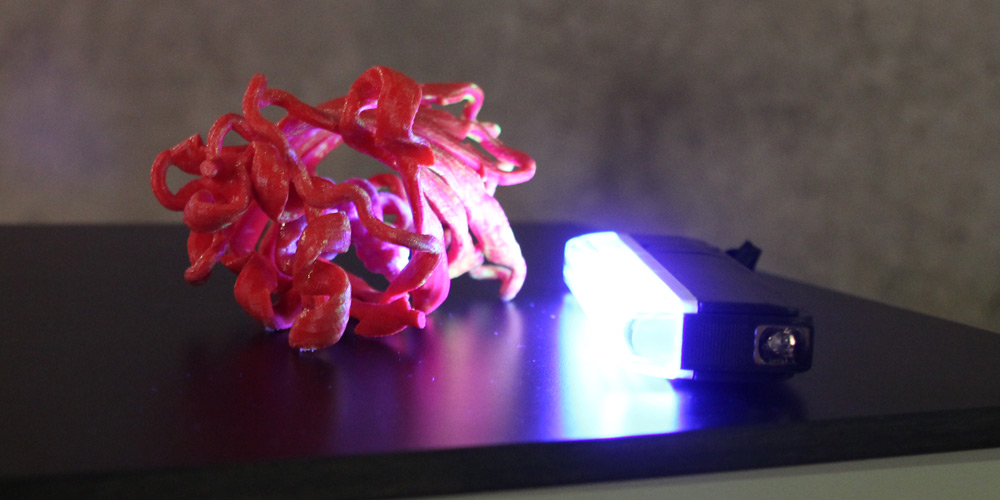

The Ars Electronica Center’s FabLab has printed out a 3-D model of a fluorescent protein. What’s that all about?

Alina Sauter: Since the FabLab is one of four labs that are part of the “New Views of Humankind” exhibition, we try to maintain connections to the other three—for instance, the BioLab, which recently became the home of a fluorescent plant. We tried the same thing with the protein of a jellyfish. To make the structure of the protein more easily visible, we first printed out the protein as a greatly enlarged three-dimensional model and then we produced the fluorescent effect. The principle of fluorescence is also utilized in genetic engineering, since once an experiment’s been carried out, it’s usually very difficult to tell if it actually worked or not. But when you use a fluorescent microscope, you can prove that the experiment succeeded, since the existence of fluorescence means that it worked.

You also presented this model at the Print3Dfuture Conference. What were some of the other main topics?

Alina Sauter: This conference featured a good mix. Some speakers discussed legal aspects of 3-D printing. Others went into potential uses in medicine, design and art. There were also edible 3-D printouts. Really, just about every area was covered. The round-table discussion on the subject of 3-D printing and copyright law was especially interesting since this topic is sure to become highly controversial in the near future. At the moment, it’s still a gigantic grey area, and everyone’s waiting for a case to set a major precedent so that the governing legislation can be updated. I’m really looking forward to seeing how this area develops in the days to come.

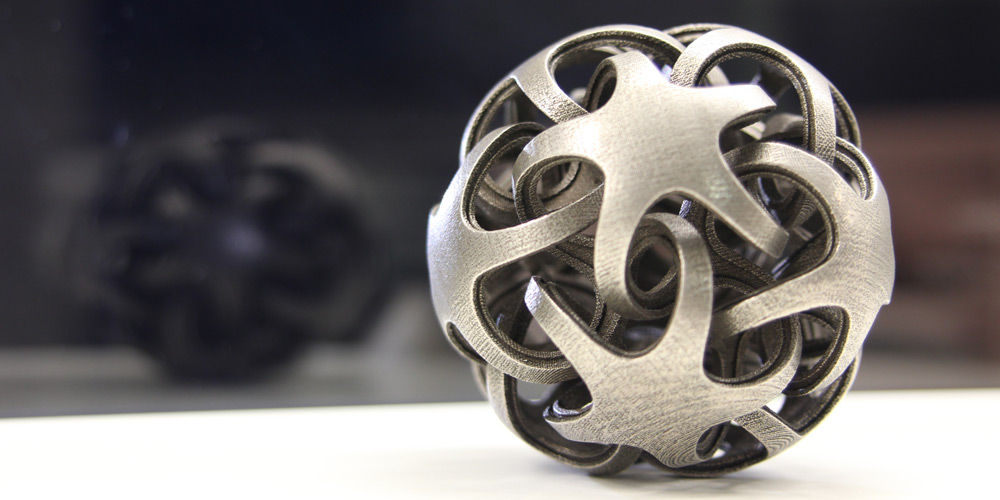

At last year’s Prix Ars Electronica, the recipients of [the next idea] voestalpine Art and Technology Grant were the creators of “Hyperform,” a project that uses 3-D printing. What’s the story here?

Alina Sauter: Marcelo Coelho and Skylar Tibbits work with folding as a means of increasing printer capacity. This concept is chiefly of interest to owners of a desktop printer, which is to say a 3-D printer that can be purchased for home use. Now, these devices feature a print bed with a relatively small size, but these two MIT researchers realized that there are ways to define forms other than in terms of uninterrupted, self-contained surfaces. So, they developed a computer-based design method that makes it possible to define the spatial volume of a body by means of a line. Then, this line is enhanced with a chain population, the result of which is that many multidirectional notches and bulges allow the line to be reconstituted into a whole object. This means that you can prepare a very large project to be printed in such a way that it takes up as little space as possible, and the end result is a printed-out object that is actually a lot bigger than the print bed of the printer.