From the uncertainty of the present to the power of art – in conversation with Gerfried Stocker, we shed light on the theme of the Ars Electronica Festival 2025.

Just a year ago, many would not have thought how quickly the world would change. Political certainties are crumbling, climatic tipping points are approaching, economic models are coming under pressure, and technological developments are coming thick and fast. What was considered stable just a moment ago suddenly seems fragile. Amidst all these upheavals, the feeling of insecurity is growing – and with it the question of how we deal with this situation. Because when worry becomes overwhelming, panic is not far away.

But what does it actually mean – panic? And how do we deal with it when collective powerlessness and a sense of hopelessness are growing ever stronger? Is panic a paralyzing state of emergency – or perhaps even a wake-up call that can mobilize forces? What does it mean to create free spaces in times of loss of control? What role does Europe play in the global power game of technology, truth and responsibility? And how much room for maneuver do we really have?

“PANIC – yes/no” is the theme of the Ars Electronica Festival 2025. Not because panic should be glorified – but because it tells us something. In a time of upheaval, we see panic not as an end point, but as a starting point for debate, for reflection, for change. Gerfried Stocker, artistic director of Ars Electronica, puts it succinctly in the interview: It’s not about glorifying panic. It’s about listening to it. Because sometimes it’s the clearest signal that change is not only inevitable – it’s already begun.

The theme of this year’s festival is “PANIC – yes/no” and raises the question of how we want to deal with change and global crises. What role can art play in directing our attention not only to the threatening aspects of change, but also to the potential it holds?

Gerfried Stocker: Anyone who has ever sat in a dark theater, experienced a concert or stood in front of a painting that unexpectedly touched them knows the kind of freedom that art creates. Not as an escape from reality, but as a pause in the middle of it. Art stops time. For a moment. And in that moment, something becomes possible that we often lose in everyday life: a change of perspective.

Particularly in times like these – when crises overlap, certainties falter and the noise of the world becomes deafening – art can become a resonance chamber. One that doesn’t pretend to have answers, but asks questions that shake us up. That touch us, disturb us, move us. That remind us that the future is shapeable – not predetermined.

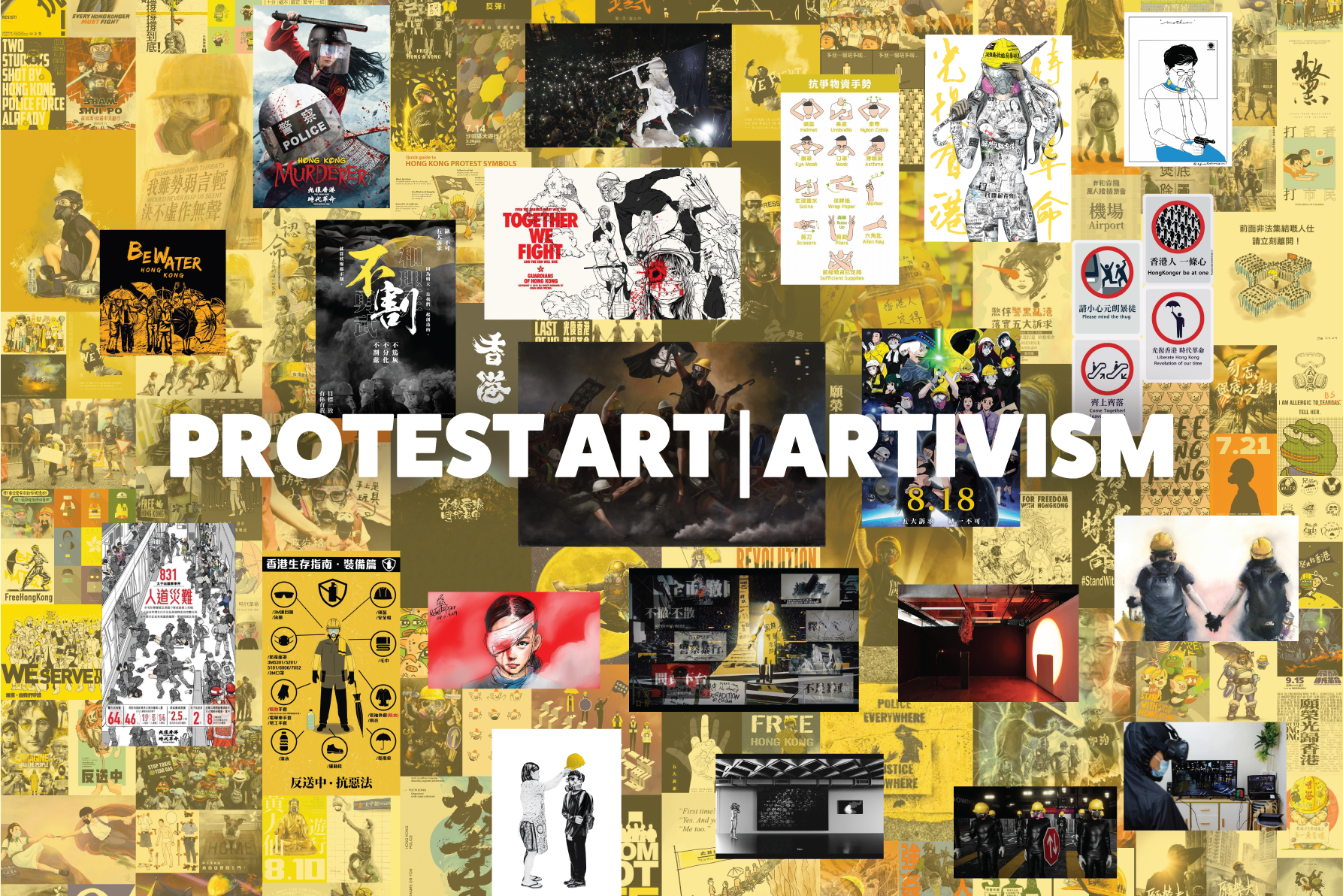

Isn’t that a paradox? Of all things, art, which “gets you nowhere”, which cannot be measured, utilized or calculated – it is art that helps us to think anew. We have been experiencing this first hand in media art for years: the boundaries between technology, society, politics and artistic expression are blurring. Commentaries become instructions for action. Reflection becomes activism. Dystopia becomes discourse. Art does not say, “This is how it has to be.” It asks, “What if it could be different?”

And yes – sometimes it takes precisely this speculative power to find a way out of the tunnel of hopelessness. To think outside the box. To allow the idea that not everything is without alternative. Because only what can be thought can be done. That is why art is not a luxury in times of confinement, but a necessity.

And if we recognize – as Bob Dylan put it 60 years ago – that “The Times They Are a-Changin’”, then we should ask ourselves: Do we just want to endure the change? Or do we want to help shape it?

In his biography “Chronicles”, Bob Dylan names Donald Trump as one of the last “individual performers” – people who create their own reality. Trump recently shared an AI-generated video of the Gaza Strip that shows a manipulated reality. Is this development a cause for alarm?

Gerfried Stocker: Yes, it is. But not in the way we know it from movies – with beads of sweat, sirens and hysterical running through the streets. Rather, it is more of a silent, subliminal panic that slowly creeps into our everyday lives. This feeling that we are losing our footing because the world out there – or rather: the digital space – suddenly questions everything we thought was true.

When Bob Dylan speaks of the “last individual performers” and mentions Donald Trump in the same breath as Socrates, it’s provocative, of course. But it’s also revealing. Because it shows how much we are living in a time when reality has become something that can be staged, produced, even trained – with algorithms, data and AI. The AI-generated video of the Gaza Strip is an example of how threatening this can be. Because it is not just fiction, but a targeted distortion. A new form of propaganda that is much more subtle than a megaphone – and much more difficult to see through. But what do we do with it? Do we let it paralyze us?

I believe we have to be careful not to fall into the actual trap: the artificially created panic. Because one thing must not be forgotten – behind every great spectre there is someone who benefits from it. When Elon Musk or Sam Altman raise a warning finger while simultaneously investing billions in their own AI projects, it is not out of disinterestedness. It’s a clever marketing strategy. And yet – or perhaps precisely because of this – we must remain vigilant. Not in a panic, but alert. Because the great danger lies not only in the technology itself, but in the erosion of our shared understanding of reality. If suddenly anyone can claim anything – and every claim gets the same amount of attention – then it becomes difficult to find orientation.

What we need is not alarmism, but a critical awareness. A kind of digital immune system.

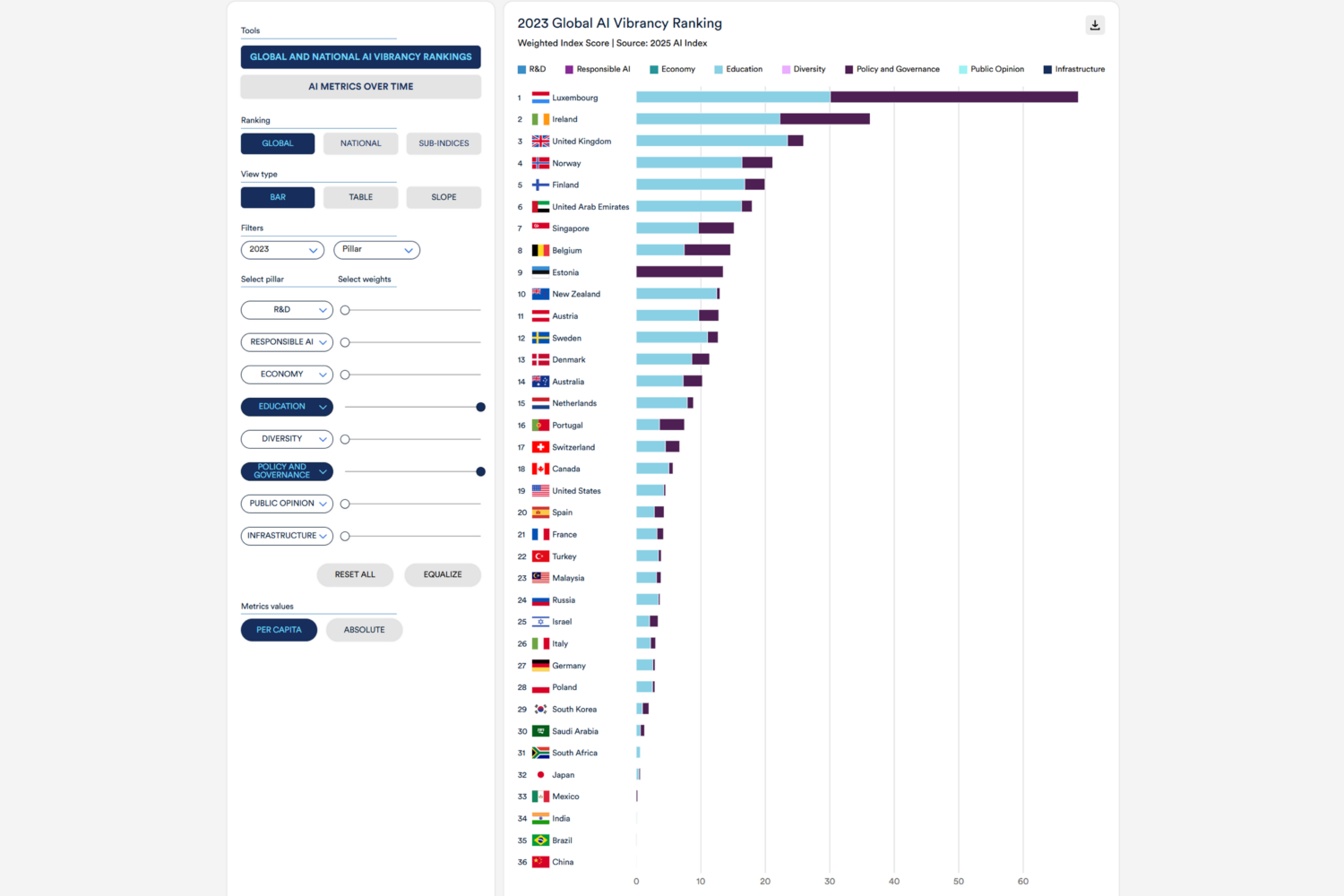

Could the European approach – for example with the AI Act – help to build a digital immune system and provide an answer to the question of the power of digital technologies?

Gerfried Stocker: I think it is the best – maybe even the only – answer we have at the moment. Even if it is far from perfect. We must not delude ourselves: In a world where political decisions hit like bullets – and I mean that almost literally when I think, for example, of what Trump has done to language, to truth – words like “regulation” or “legislative proposal” sound pretty powerless at first. What use is the best strategy when the next one just slams his fist on the table – or, even worse, presses the trigger?

But that is precisely why we need this European approach. An approach that relies not on volume, but on reliability. Not on market size, but on principles. The AI Act is not a panacea – but it is a start. A political gesture that says: we can do things differently. And we want to do things differently. It’s easy to forget that Europe is a very powerful economic area. And that in a global, interconnected economy, one thing matters: trust. Without trust, nothing works. No online shopping, no digital health system, no AI application that deeply impacts our daily lives.

And this trust does not grow out of naive hope, but out of clear rules. Out of the knowledge that if someone goes off track, there will be consequences. Just like in traffic – the system works because we know that if you constantly drive through red lights, you will lose your license. This is the foundation on which Europe can and must build. Because in the global AI race, we will never be the ones collecting the most data or building the fastest systems. The US and China are simply too big for that. But we can be the ones to show how to do it well. How to handle data in a way that not only leads to innovation but also to responsibility. How to embed AI in an ethical framework, in democratic processes, in social justice.

This may sound very idealistic, but it is realistic. Because in the end, it is people – the users, the voters, the consumers – who decide who they trust. And if we manage to develop products that not only work, but are also comprehensible, fair and transparent, then that is not a disadvantage. That is our competitive advantage.

Is the European approach – i.e. safe, privacy-compliant AI – in demand outside of Europe at all? Especially in the Eastern region? Or is this a typically Western understanding of technology and society?

Gerfried Stocker: We in Europe are different. The high value we place on individual freedom, the emphasis we put on data protection, the responsibility we feel for the common good – these are not empty phrases, but deeply rooted attitudes. And of course, in China or in parts of the United States, the priorities are different. There, it has historically been the case that the state – or large corporations – are allowed to intervene more deeply in people’s personal data space. In Europe, on the other hand, we have learned that trust is not created through control, but through transparency, rules and responsibility.

Now you may say: fair enough, but does anyone outside the EU care? Are we selling AI systems to Beijing or Washington? Probably not. But that’s not the point either. The real question is: do we as Europe want to be a follower – or a shaper? Do we want to catch up – or lead the way? I firmly believe that our approach gives us a huge opportunity to set global standards, too. Not because we are the loudest or the fastest, but because we can show how things can be done differently. How technology can be combined with ethics, innovation with responsibility, progress with a sense of proportion.

We often underestimate our own strength. If we look at Europe as a whole, we see a space with great creative power. This applies not only economically, but also socially and technologically. Our strength lies not in the volume of data, but in our ability to use it sensibly and responsibly. We don’t just develop AI – we integrate it wisely into structures that are based on trust.

Because one thing is clear: AI is not an off-the-shelf product. It is a process, a challenge that requires care and responsibility. Anyone who has ever implemented a complex IT system knows that it takes more than technology. It takes attitude.

We have already talked a lot about the “Yes” of panic – about those who profit from it and our fears. But the festival title also contains a “No”. What does this “No” mean to you – and what does it include?

Gerfried Stocker: The “No” in the festival title is much more than a simple no. It is a pause for thought – a moment of clarity in the midst of the noise, a mental stop signal in the stream of overwhelming demands. Because if we are honest, given all that surrounds us – climate collapse, wars, AI overload, social division – collective panic would have been logical long ago. But it is not happening. No mass exodus, no hysteria. Instead: astonishing silence.

And that is precisely where the “No” begins. It shows us not only how much we already live in a state of emergency – but also how much we tacitly accept it. This calm is not a sign of composure, but an expression of being overwhelmed. We feel that something is tipping over, but we are rooted to the spot. Perhaps out of fear, perhaps out of disorientation.

But this “No” is not a retreat. It does not deny reality – it contradicts it. It says: it cannot go on like this. It reminds us of all the almost overlooked turning points of recent years – the political, ecological and social tipping points that we almost crossed. And it asks: why haven’t we reacted louder? When did we forget how to stand up?

But it is precisely in this question that the power lies. The “No” is not an end, but the beginning of attitude. It is not resignation, but determination. It is an invitation not to panic – but to remain capable of action. Not to say: “That cannot be changed”, but: “We can do something.”

And maybe, just maybe, something is starting to happen. Not loudly, not spectacularly, but noticeably. In art, in thinking, in small political shifts. The “no” is not a break. It is a caesura. A clear rejection of indifference – and at the same time the space in which new paths become visible.

Is the festival theme meant as a call for collective panic to provide an impetus for change and action?

Gerfried Stocker: A call for collective panic? No – at least not in the way you might imagine at first glance. I don’t want to see a society that breaks out in hysteria, goes around in circles, or retreats into the corner in apocalyptic despair. But I do want a society that looks. That feels. That no longer pretends that this is all just a temporary storm that we can sit out.

What I mean is: maybe we don’t need panic in the sense of loss of control – but panic as a signal. As a physically and emotionally tangible moment that shows us: we have now reached the point where just watching is no longer enough. Because, let’s be honest: what would have to happen for us to wake up? Are wars, burning forests, collapsing democracies and a planet that shows us its exhaustion every day not enough? We have become masters at coming to terms with things. With the climate crisis. With digital surveillance. With growing inequality. And that’s human – but it’s also dangerous.

That’s why the festival theme for me is not a cry of “Run!” but a call to “Look!” It’s an invitation to face our own restlessness. And it is precisely from this that action can arise. Not actionism, not blind protest – but conscious, self-determined recognition: we have reached a point where “carrying on as before” is no longer an option.

What we are trying to do at the festival – and I think this is more evident than ever this year – is to honestly strive for understanding. Not everything is clear. Not everything has a solution. But we have to start asking the right questions – even if they are uncomfortable.

Were you aware when choosing the festival theme “Hope” last year that we would end up with “Panic” a year later?

Gerfried Stocker: No, if I had known that we would have panic a year later, I would never have suggested “Hope”. I couldn’t have – out of respect for hope itself. Because back then it was real. Not a naive, rosy hope, but one that you work hard for. A hope in the face of crises – but also in the belief that change is possible, that we can make a difference if we really want to. I still remember the feeling in the team well: we wanted to encourage people. Hope as an attitude, not as an illusion.

And yes – there was already enough to worry about back then. The climate crisis was not suddenly new, nor were the social tensions surprising. But there was also movement: more awareness, more activism, more political and technological upheaval. It seemed as if something could tip over – in the best sense. What we are experiencing today is also a tipping point. But in the other direction. The tone has become rougher, the language more aggressive, the leeway narrower. And Trump’s return is just a symbol – a glaring, loud, frightening marker. The actual shock lies deeper. It runs through institutions, through global alliances, through our way of communicating, of doing business, of living.

But wasn’t the hope at that time already strongly linked to climate change, too?

Gerfried Stocker: Yes, absolutely. The hope back then was essentially linked to climate change. And not because we underestimated the crisis – quite the opposite. We knew how dramatic the situation is. That it is about nothing less than “getting the curve” – in the truest sense. That many of these tipping points may have already been crossed. But still, there was this feeling: something is happening. There was a sense of awakening in the air. Fridays for Future was no longer a marginal phenomenon, but a global movement. The debate had arrived in the middle of society – in the media, in parliaments, in people’s minds. Even in the business world, awareness was growing: the energy transition is not only ecologically necessary, but also an economic opportunity. A new playing field for innovation, technology, future markets. And Europe was finally beginning to realize this.

And then Trump came back. Or rather: the threat of his return. And it was immediately clear what that meant. That climate policy would once again be held hostage by an ideology. That environmental standards would be sacrificed for the sake of coal, oil and short-term economic interests. At the same time, the “Green Deal” in Europe suddenly became the “Clean Deal” – and instead of decarbonization, the focus was on armament.

Is the festival theme also taken up in the artistic projects? Are there already concrete approaches or directions?

Gerfried Stocker: The festival’s artistic projects arise from a vibrant network of conversations, shared experiences and constant exchanges with artists worldwide. Often it seems as if the theme finds itself. Because it is in the air. Because people in completely different places feel similar things.

And what is currently being felt is intense: exhaustion. Frustration. Powerlessness. But also the desire to act, to “nevertheless”. The questions that arise from this are existential: How do we want to live? How to continue working? And: Is independent art even possible anymore – in the face of increasingly politically charged cultural debates and economic pressures?

These tensions are reflected in the works. Some artists react directly – with clear, activist positions. A good example of this is the work “Pollinator Pathmaker” by Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, as well as the S+T+ARTS Afropean Intelligence initiative. Others create poetic counter-spaces, allow silence to speak, or imagine new futures. Both are important. Because art doesn’t have to solve anything – it’s allowed to disturb. It asks questions where others remain silent. It creates spaces where systems close. And it tolerates contradictions without smoothing them out immediately.

A special example is the opera “Der Kaiser von Atlantis”, which will be performed during the big concert night in the Gleishalle of the Postcity. Created under unimaginable conditions in the Theresienstadt ghetto, it shows impressively that art does not disappear in the face of repression – it becomes all the more powerful, touching and necessary.

You can find more about the Ars Electronica Festival 2025, which will take place from September 3 to 7 in POSTCITY Linz and numerous other locations throughout the city, here.

Gerfried Stocker

Gerfried Stocker is a media artist and engineer in communications technology. He has been Artistic Director and CEO of Ars Electronica since 1995. With a small team of artists and technicians, he developed the exhibition strategies of the Ars Electronica Center in 1995/96 and established a research and development department, the Ars Electronica Futurelab. Under his leadership, the program for international Ars Electronica exhibitions was developed from 2004, the planning and repositioning of the Ars Electronica Center, which was expanded in 2009, began in 2005, the Ars Electronica Festival was expanded from 2015, and the Ars Electronica Center was extensively redesigned in 2019, both thematically and in terms of its interior architecture. Stocker advises numerous companies and institutions on creativity and innovation management, and is a guest speaker at international conferences and universities. In 2019, he received an honorary doctorate from Aalto University, Finland.