The Hollywood Walk of Fame is only a 30-minute Metro ride from the Walt Disney Concert Hall. For its “30 minutes of fame,” the Futurelab gladly took the 9,716 km trip from Linz to Los Angeles. After all, the invitation to visualize Ravel’s “Mother Goose” in conjunction with the L.A. Phil’s inSIGHT Series is a prestige project—and, as if that weren’t enough, a well-paid job too! To do justice to this assignment, let’s not omit mention of the three other classical pieces that were performed on three successive evenings: abstract visualizations of performances of Tanguy’s Affettuoso, Correspondances by Dutilleux and Poulenc’s Organ Concerto in G minor provided the lead in to what was undoubtedly the program’s highlight.

The premiere was on February 12th. Soon after the applause had faded, we talked about the project to Gerfried Stocker, artistic director of Ars Electronica, and Horst Hörtner, head of Ars Electronica Futurelab.

Let’s cut to the chase, guys: How was it?

Gerfried Stocker: Great.

Horst Hörtner: Overwhelming.

Is there a difference in audience acceptance of such modern visualizations of classical works in the Land of Unlimited Possibilities?

Gerfried Stocker: Generally speaking, music visualizations are difficult terrain in Austria too. We’ve been doing this for 12 years now, and the question of synesthesia has been raised incessantly. Music aficionados, musicologists and composers often complain that the visualizations are just a distraction. In other words, in creating any concert visualization, the utmost priority is to avoid a competition for the audience’s attention, which obviously does no one any good. Of course, this always depends on very specific, non-generalizable aspects—for instance, in every case the architecture of the concert hall itself exerts a major influence on expectations.

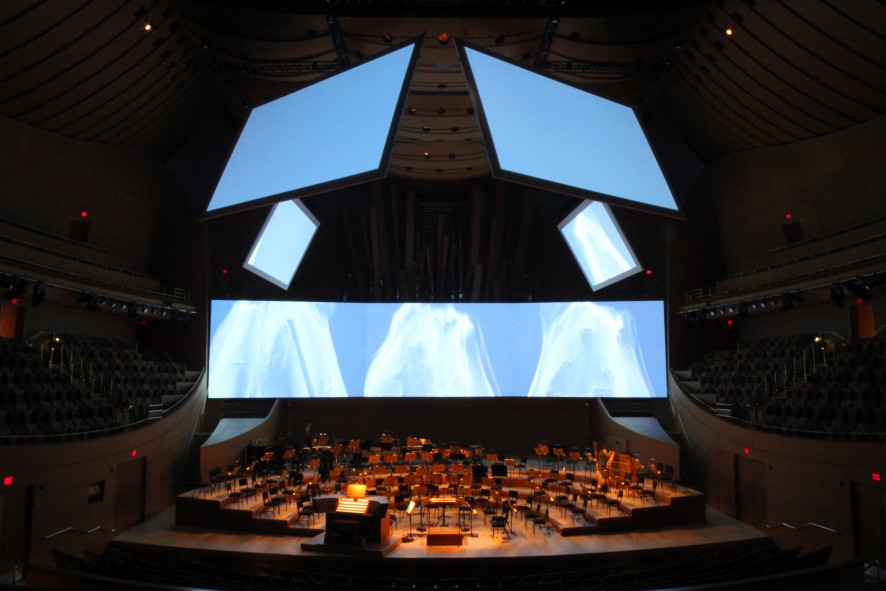

“The exciting thing about working the L.A. Phil’s venue is going head-to-head with Frank Gehry’s striking spatial architecture. What it brings forth is a sort of ecosystem of attention that several protagonists have to share. There, we set up no fewer than seven projection surfaces, no small-time competitor … and also a reason why we visualized not just ‘Mother Goose’ but the whole lineup.”

Florian Berger (left) and Gerfried Stocker (right) are setting up the equipment. Credit: Roland Aigner

Horst Hörtner: For the first three pieces, we use only six of the seven screens. All seven don’t come into play until “Mother Goose.” The screens are dispersed symmetrically in the concert hall, above and behind the orchestra, and in such a way that audience members seated on all sides have a really excellent view.

Who actually came up with the idea of taking the concert ballet version of Ravel’s fairy-tale cycle and transposing it into the world of abstraction?

Gerfried Stocker: The idea of the abstract visualization of “Mother Goose” came from conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen. He requested that we get away from the classic approach of the ballet performance since his interest in the piece was focused on its qualities as a sound painting. It’s really fascinating to hear how he has developed the piece over the years and brought out the individual tonal colorations of the orchestra. And that was actually the impetus behind our visualization, which, since the very first meeting in April 2015, moved further and further away from a strictly literal orientation on the work’s plot.

Totally wired: The Futurelab’s hardware is set to go. Credit: Roland Aigner

For instance, in the sequence from “Beauty and the Beast,” we show the antagonism between the original figures in the form of a morphing landscape. To achieve this, we developed a program that gives the computer paintbrushes with which it can use the piece’s tonal colors to paint these landscapes. The ambiguity of the relationship between “beautiful” and “beastly” is expressed in terms of the fragile, constantly changing landscape. That might be a pretty high degree of abstraction if you consider the plot, but not when you reflect on the music itself.

Even with this high degree of abstraction, isn’t there nevertheless a stylistic framework?

Horst Hörtner: Since this is a piece that Ravel wrote for children, the visual elements are almost kitschy. But no more than almost—what I’m trying to get across here is that the visuals are touchingly beautiful. We developed a visual language that comes across as if it were painted, and we weave into it classical elements from the art historical epoch that prevailed at the time this piece was composed—that is to say, the precursors of Impressionism and experimentation in architecture, as well as the genre that, in turn, led up to them, which is to say Romanticism.

La belle & Bete Visualization by Ars Electronica Futurelab. Credit: Roland Aigner

La Laideronette Visualization by Ars Electronica Futurelab. Credit: Roland Aigner

Gerfried Stocker: An innate part of the artistic process is erecting a framework upon what is done. Since art offers a panopticon of comparisons, the aspect of influence upon action that Horst just described emerged and subsequently gave rise to this core element.

Let’s go into the live factor … concertgoers expect something unforeseen and, especially in the case of digital art, the question arises as to where’s the human element behind all this? How do you respond to the prejudice that these visualizations could just as easily have been a screensaver?

Gerfried Stocker: We probably undertake more spontaneous interventions in our artistic performance than the perfectly coordinated members of the L.A. Philharmonic Orchestra! We’ve been rehearsing over the many months we’ve been developing this project. First of all, you study the score or you work off a CD recording. The visualizations thus emerge module by module, and then you have to sort of teach the computer “to behave” in a predefined way in every musical situation. That’s where the artistic process begins. We orient ourselves, measure for measure, on the arrangement, and we know what we want to say … how we then play this out is composed according to a comprehensive concept. The formal metamorphosis emerges from the timbre of the respective instrumental groups.

Seven screens going head-to-head with Frank Gehry’s striking spatial architecture of the Disney Hall at the L.A. Phil. Credit: Roland Aigner

Horst Hörtner: The interplays on which our colleagues Florian Berger and Roland Aigner concentrate during the live mix function as connective links, and are orchestrated by means of the shadows cast by the musicians. They’re arranged like the REM phase a person goes through when sleeping—a sort of half-sleep. In this sense, the shadows make the interludes somewhat “more objectively representational.” One imagines one is dreaming the story of “Mother Goose” and is repeatedly awakened during the course of the dream. During these intervals, the musicians make visual inputs, or, to put this in different terms, live camera shots shift them into the focal point of the performance. But these shadows aren’t entirely representational; they too are rather abstracted. One recognizes within them, perhaps, a monster marching through the scenery. It becomes a mixture of a live mix among the “dream generators” and a live mix among the shadow generators and a live mix of these live mixes. Gerfried produces the dreams and I, as master controller, then mix together the various visual inputs. I’m what you might call last sovereign decision-maker prior to the projection.

A test run of the visualization before the final rehearsal. Credit: Roland Aigner

Following this fabulous—in both senses of the word—performance, the L.A. Philharmonic’s Associate Director of Artistic Planning, Meghan Martineau, gave rave reviews to their collaboration with the Ars Electronica Futurelab crew.

How did the Futurelab come to the attention of the L.A. Phil?

Meghan Martineau: We became acquainted with the Ars Electronica Futurelab courtesy of Princess Irina of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg, the international representative of the Abu Dhabi Festival, who’s currently involved in several projects with our musical director, Chad Smith, and, due to her contacts with Gerfried and Horst, is also familiar with Ars Electronica. She was so enthusiastic about the extraordinary things that are happening in Linz that Chad got in touch with them a year and a half ago. He too was so excited by the transdisciplinary, forward-looking approach that everything clicked. Right off the bat, the decision was made to work together with the Futurelab. At that point, we were involved in planning our 2015-16 season but, based on the time lags as measured in our business, a year isn’t very much lead time in which to integrate an act like this.

“Chad was absolutely convinced that collaboration made sense because the L.A. Philharmonic and the Ars Electronica Futurelab are on the same wavelength when it comes to blazing new artistic trails. And the shared mode of progressive thinking, how one goes about establishing a connection to an audience, also spoke in favor of this synergy.”

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor Philharmonia Orchestra. Credit: L.A. Phil

What was the difference between the Futurelab’s approach and those of the other artists who produced visualizations in conjunction with your inSIGHT Series?

Meghan Martineau: All the artists involved in the inSIGHT Series have highly divergent approaches. For example, last season we had Steve Reich and Beryl Korot with “Three Tales,” a video opera and thus an audio-visual composition. With the Ars Electronica Futurelab now, we have a composition from the early 20th century that’s being visualized in retrospect and, moreover, in an abstract way. This tremendous interpretational latitude means the emergence of something totally new and original. Needless to say, the music itself can’t be modified, so the challenge is to clear up all uncertainties in advance so that a meaningful work of art can take shape. The extraordinary thing about the Futurelab’s methodology is the input of the audio feed, which generates images by means of a programmed code. This is a totally unique approach.

How did conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen come upon the idea of an abstract visualization?

Meghan Martineau: Now, everybody’s familiar with the Mother Goose stories; everyone has pictures in their mind of Hop o’ My Thumb or the bad guys in the individual segments. The idea was to get the audience members to take leave of their preconceived images and to immerse themselves in the mood of the individual narrative strands. Based on our experiences with the first visualizations in 2003-04, we came to the conclusion that these experiments strongly appeal to the audience. The inSIGHT Series is simply a manifestation of what we regard as our program’s top priority—blending together different art forms. Last season we had, in comparison to Ravel, Beethoven’s “Missa Solemnis,” and the audience reactions were incredibly positive. Concertgoers and critics alike agreed that the visualization only contributed to a better understanding of the composition.

“We set the bar very high this season with the Ars Electronica Futurelab, the most technically demanding team we’ve ever worked with. The screen installation alone is quite extraordinary. Never before have I seen anything like this! It makes the impression more all-encompassing than ever before.”