The 2017 Ars Electronica Festival kicks off with an impressive lineup of fascinating speeches. The opening symposium entitled “How Culture Shapes Technology” will initiate what is sure to be highly stimulating interaction with important ideas over the coming days.

Festival Friday, September 8th, carries on the concepts introduced on Day 1 in the context of an extensive symposium focusing on this year’s festival theme, Artificial Intelligence – The Other I. In four themed clusters, experts will delve into various aspects of artificial intelligence (AI) including the contrast between expectations and reality, ethics, and creativity with AI, and range across a broad spectrum of approaches, ideas and content.

One of the highlights is a speech by Mark Coeckelbergh. The professor of Philosophy of Media and Technology at the University of Vienna will offer insights into the extent to which machines can actually create art. We recently sat down with this technology expert for an interview in which he went into what he sees as the link among artificial intelligence, art and culture.

The pictures show artworks from the theme exhibition POINT ZERO. Here: “Reading Plan” by Lien-Cheng Wang. Credit: Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts

At this year’s Ars Electronica Festival, you are one of the speakers of the opening symposium „How Culture Shapes Technology“. Usually, we talk about how technology influences culture and not the other way round – now what makes this „reverse reflection“ so interesting?

Mark Coeckelbergh: Usually we think of technology as separate from culture, as something purely technical. But as I argue in my recent work, for example the article “Technology Games” or my new book “Using Words and Things”, technology is always embedded in games and in a form of life. When we encounter new technologies such as robots and artificially intelligent devices, we give meaning to these technologies by relying on what we already know and how we already do things. Technologies can be game changers, but my point is that this is only possible because there are already games. There are already shared ways of doing things, shared practices, which give meaning to the technology. In this sense, culture shapes technology.

But culture should not be understood as a kind of separate thing or as having nothing to do with technology. It only exists in living practices, also in our use and interaction with new and emerging technologies. Technology is cultural, and technology is human – just as much as humans are technological. Technology has all the beauty of the human and embodies all the suffering and problems of human culture. Technology and culture are entangled.

“Ad lib.” by Michele Spanghero. Credit: Vanessa Graf

The theme of this year’s festival is „Artificial Intelligence – the Other I“. How does AI play into the process of culture shaping technology? Which effects can we see today?

Mark Coeckelbergh: When people respond to new developments in AI, they already have a particular idea in mind of the human being. Often that idea includes that humans are not machines. In the West we generally think it is very important to distinguish between humans and non-humans. Then it is important to guard and defend the border. Posthumanists have less problems with that, they question traditional differences and recommend crossing boundaries and a more inclusive attitude towards non-humans, be they natural or artificial. So in and behind the technology is an entire cultural field with ideas and practices concerning how to relate to non-humans.

Also, some artificially intelligent agents may appear as human-like. That’s because we are social beings and have already a kind of repertoire ready to respond to anything or anyone that appears as other. We already know the social games. If we meet a robot, all this comes into play. To create machines that appear as quasi-others also has a long history in our culture, ranging from the Golem and Frankenstein to contemporary science fiction films such as Ex Machina. Apparently there is a desire for an artificial other, or perhaps for an other tout court. AI and robotics play into a field of social relations and ideas about social relations. If there are problems in society with social relations, for instance about gender and about people having difficulties with romantic relationships, these are mirrored into the technologies. Again, technologies are not only technical, they are human and cultural at the same time.

“Sculpture of Time” by Akinori Goto. Credit: Akinori Goto

AI raises also interesting question about human art and creativity, usually seen as part of “high” culture. We see that robots create art, for instance. But does it really count as art? What is art? What is creativity? Are creative technologies a problem, or can we accept them as co-creators? Could they maybe have a different form of creativity? Is that a problem or an exciting new area, opening up new possibilities for human culture? Is human culture anyway hybrid, human and non-human? I will say more about all that in my talk. But here my point is: it’s the technology, it’s AI and robotics that create cultural challenges and possibilities. AI and robotics force us to ask key questions about what it means to be human and what culture is and should be.

“Nyloïd” by Cod.Act. Credit: Xavier Voirol

Technology, as part of human culture, is always an expression of the times. How have different cultures in the past shaped technology? How do social and cultural influences manifest themselves in technologies nowadays?

Mark Coeckelbergh: That’s right. But one could see technologies not so much as expressions of the times but rather as a kind of cultural tools. They are used as instruments to engage with the pressing questions of the times. When I did research for my book “New Romantic Cyborgs” I noticed that in the 19th century romantic thinking was interwoven with technology development, to such an extent that some talk about “romantic machines”. But this is not only true for the past. I argue in the book that romantic thinking still shapes our technologies and how we use them. For example, we use technologies to escape to a different reality, to bring back the magic we think is gone, or we use them to overcome divisions between mind and matter. All the cultural problems and challenges of modernity return in our technologies. Resistance is futile; better deal with them.

More generally, today we see that in the discussion about artificial intelligence a lot of questions of our time return. For example, a big social and political issue today concerns justice and inequality. There is the feeling of crisis and there are protests. There are also worries about climate change and what we do to the environment. Now we can observe that in the discussion about AI these questions return. Suddenly tech people, not politicians, talk about basic income and talk about the risks of AI. Tech people, not politicians, propose solutions for environmental problems. Of course there is also policy. But the point is that technologies, as much as discourse and policy, play a role. In the political theatre, AI and electric cars are on the same stage as people and discourse. Social and political questions mix with technological and scientific questions.

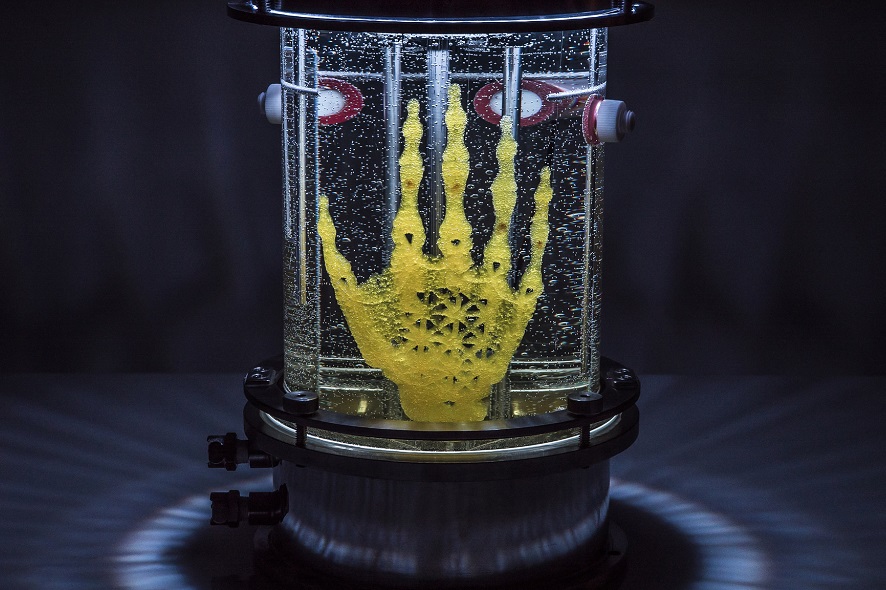

“cellF” by Guy Ben-Ary. Credit: Rafaela Pandolfini

Are there clearly discernible differences between different cultures?

Mark Coeckelbergh: There are differences. For example during my work on ethics of robotics I found out that Japanese researchers had much less problems with human-like robots than people in the West. In the West we think it is really important to clearly distinguish between humans and non-humans. But I talked to a Japanese researcher and he simply didn’t see what this was so important. So yes, there are differences.

On the other hand, there is no such thing as a homogeneous culture like “the West”: there are all kinds of subcultures, some of which are very open to the new technologies. And I also think we should avoid orientalism and similar –isms: Japan is not an entirely different culture, it is also shaped by modernity, it is a different, alternative modernity. Cultures are hybrids, they are monsters, they are ecologies of different cultural lifeforms, with all kinds of beautiful and ugly sides to it. And in Western modernity there has always been a romantic longing for a pre-modern past. So yes, there are differences, but let’s not exaggerate the differences. We are all humans and we all interact more or less intensely with technology and depend on it for our lives. We are all cyborgs, in this sense.

“Singularity” by Kathy Hinde and Solveig Settemsdal. Credit: Solveig Settemsdal

Your latest book discusses language and technology. Does language, often used as an important marker or manifestation for culture, play a significant role in shaping technologies? Which other cultural factors do you think are important in the process?

Mark Coeckelbergh: Language is very important in the shaping of new technologies, since like other instruments and tools it gives form to the meaning and use of the technology. In my most recent book “Using Words and Things” I give the example of social robots. The invention of social robots, machines that interact with humans in a way that tries to imitate human to human social interaction, was as much a technical matter as a linguistic one. By coining and using the term “social robots”, researchers in the field try to tell us that they are friendly, that they are ok, that we can easily and safely interact with them, and that the imitation of the social has succeeded. But one can question this, and ask also about the ethical and societal implications. Such critical work needs to engage with the engineering and the science, but also with the language.

Also, language plays an increasing role in artificial intelligence and robotics: to make these devices more intelligent and indeed more “social”, a key component is a linguistic interface, and today increasingly that takes the form of a voice interface. We will get more devices that talk to us. Our perception of these machines and devices will depend a lot on how language is used and handled by the interface. If the linguistic exchange appears “natural” – social – then we will treat these devices as others. Is this deception? Is it problematic? Do we really want this technological version of Alice in Wonderland? Do we want artificial “friends”? Is it merely used by the company to better capture our data, which are then sold off to other companies? Or is it totally fine? Should we give in to this technological world of comfort and seduction, this internet of magical things?

To answer these questions, other cultural factors come into play, which are already mixed with the language we use to talk about these issues: our beliefs and values. Faced with the new technological developments, we should think harder about what kind of society and what kind of world we want and what kind of lives are worth living. Not in order to reject technology, or to do thinking apart from technology, this is anyway impossible. Rather, we should do it in order to find out what kinds of technologies we want to live with. Which is basically the same question as asking what kind of culture we want to have.

Mark Coeckelbergh is Professor of Philosophy of Media and Technology at the Department of Philosophy, University of Vienna, and (part-time) Professor of Technology and Social Responsibility at De Montfort University, UK. Currently, he is President of the Society for Philosophy and Technology. His publications include Growing Moral Relations (2012), Human Being @ Risk (2013), Environmental Skill (2015), Money Machines (2015), New Romantic Cyborgs (2017) and Using Words and Things (2017) and numerous articles in the area of philosophy of technology, in particular the philosophy and ethics of robotics and ICTs.

At the conference on this year’s festival theme, Artificial Intelligence – The Other I, on Friday, September 8, 2017, Mark Coeckelbergh will talk about whether machines can create art. He will also speak at the Opening Symposium on Thursday, “How Culture Shapes Technology”. He’s part of an extensive lineup of outstanding experts in their respective fields—complete details will be posted on our website in the coming days.

To learn more about the festival, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter and visit our website at https://ars.electronica.art/ai/en/.