Ciutat Vella’s Land-use Plan – the name of the winning project of this year’s STARTS-Prize in the category “Innovative Collaboration”. Collaboration is what it’s all about: In order to reach a broad consensus for the further development of the historic old town district of Barcelona, architects and urban planners, editorial teams and data scientists, lawyers and specialists for real estate and business licences, public institutions and, last but not least, the citizens themselves are involved in the project. Machine learning and Artificial Intelligence are used to process the flood of data in a meaningful way. We spoke with Mar Santamaria and Pablo Martínez, the main authors of the master plan.

Ciutat Vella is the historical city center of Barcelona. What is special about it? And what makes it need new thoughts on city planning

Mar Santamaria: For decades urbanism has focused in urban peripheries to make new city, relegating the old center to the symbolic values; in many cases, deserting them and placing historical town centres in the hands of economic power, whether large companies or higher incomes.

Unlike other historical centers in Europe and around the world, the old town of Barcelona is still an inhabited, dense and popular residential area with very diverse segments of the population that coexist in an urban fabric with unique historical and heritage values (resulting from a urban morphology of narrow streets and small plots). This fabric concentrates, at the same time, large cultural facilities and elements of interest (such as squares and markets) both for the citizens of Barcelona and for visitors from all over, in an area that also has a great centrality and is very much connected at the transport level.

Pablo Martínez: All this makes the district a very busy area, with a very dynamic economic activity. It is a commercial fabric of great diversity and mixed use – although over the years, local commerce has made way for leisure activities and nightlife, in addition to tourism. Today, this economic activity (specifically that of public establishments such as restaurants and night venues) is generating a negative impact on the environmental quality of the district, which results in noise and cleanliness, concentration of people in public space or over-crowded streets due to logistics that serve the commerce. The mixture model, so positive to ensure good urban quality, is at the moment a source of conflict.

In this context, this particular type of economic activity must be regulated through a urban planning that guarantees the balance between commercial establishment and the necessary quality of life in the district. The challenge is to fit within the contemporary standards of habitability a fabric that, because of its origin, state of conservation and periodical transformations, is very vulnerable.

Credit: Jorge Franganillo

What are your general thoughts about urban planning?

Pablo Martínez: We understand urban planning as a tool to guarantee the quality of life of citizens. Urbanism protects the urban model, in other words, it defines in a territory how life develops in various aspects (social, economic, etc.).

Today, a change is needed in the way of making urban planning that is motivated, on the one hand, by a greater ability to read and model the city based on novel analysis techniques (fueled by big data and machine learning/AI) and, on the other, by a new urban paradigm of no growth (embodied by European cities) that demands to have a greater knowledge of the environment.

Technology is a very important driver in this change, which enables to include new layers of information describing urban behaviour (like trends, time, citizens’ interactions) into planning processes and complement traditional approaches based on the urban form.

However, this same technology -which currently allows us to build complex models informed by big data and it is at the origin of the new forms of participation and technopolitics-, is responsible for the irruption of recent urban phenomena related to digital economy and platform economy, such as tourist rental or mobility on demand, that are also changing the way of regulating within cities.

In this context, we need to generate a new type of urban planning that has to be more scientific, that is to say, allowing us to measure the different phenomena, generate replicable and comparable methodologies, build common indicators in order to redefine goals in favor of a greater urban habitability (that combines residence, economy, transport, environmental sustainability among others).

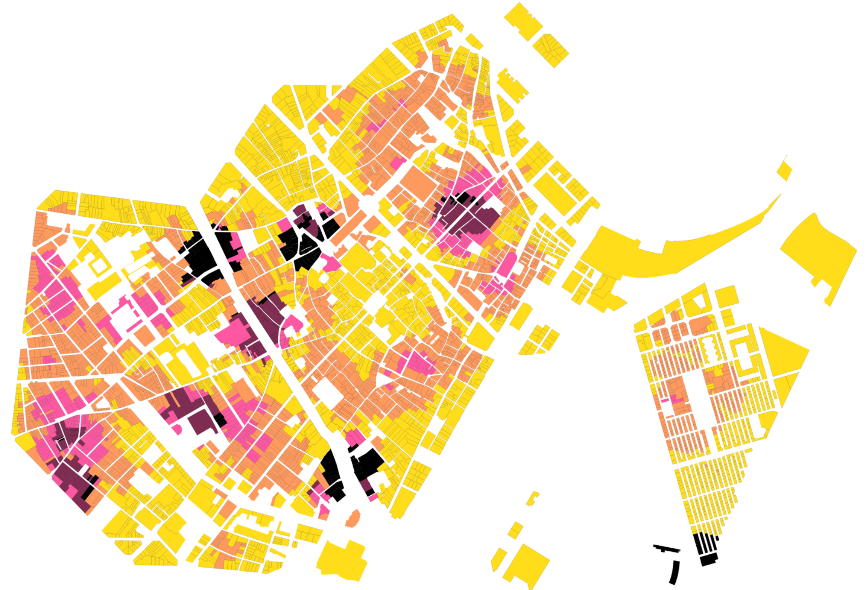

Saturation: Data model of economic activities

You won the STARTS Prize for Innovative Collaboration – who is part of your network? And how do you influence each other?

Mar Santamaria: The drafting process of Ciutat Vella’s land-use plan consolidates a new way of making urban planning that, in recent years, aims at achieving greater involvement and coordination of all agents: drafting team, sectoral experts, participation facilitators, public bodies and citizens.

In the first place, the drafting team (300.000 Km/s) is formed by an interdisciplinary group of professionals arising from complementary fields of knowledge – a mix of architects and town planners with data-scientists, lawyers and specialists in real estate and business licenses- who are nourished by this variety of disciplines. We are a very active agent in the architecture and technology ecosystem of Barcelona, mainstreaming entities and generating a network with other professionals and civil society. We act as a bridge between experts, public bodies and citizens.

As for the participation team (regular collaborator), they provide us with qualitative data about the environment. The cooperative “Raons Públiques” structures participation processes, having great knowledge of agents operating in the territory and how they have to involve them.

The City Council, promoter of the plan and in charge of its administrative procedure, has co-authored the document. It has involved all the political and technical teams of both the district and the city (urban planning and legal departments) and has offered the means to generate a fruitful debate through the digital platforms of participatory democracy, the interaction with all political groups or the direct explanation to neighbours and entities.

Finally, citizens have collaborated directly – either by participating in person or digitally in the process of citizen participation both in the diagnosis and in the proposals or contributing with their feedback during the period of allegations – and indirectly in the process, being protagonists of a diagnosis made with data that puts the focus on how the citizen behaves.

Credit: 300.000 Km/s

What would you consider the challenges of the participation of citizens?

Pablo Martínez: Today, citizen participation in Europe in its various forms (civil society participation, electoral participation, direct democracy, etc.) is in a pretty good shape. Specifically, there is a legal framework in Barcelona that recognizes the importance of participation at the local level and normalizes it as one of the parts that must have any planning process (with the consequent risks of professionalization and fatigue by citizens).

In this context, the challenges of participation go, first, to understand participation both as a decision-making tool and as a diagnosis, being necessary to incorporate various dimensions of citizens: from the more qualitative information obtained in direct interaction during participation sessions up to the numerical modeling of data (demographics, economic transactions, social networks, wifi infrastructures, among others) that allow us to draw the citizen in the plan cartographies in a qualitative and quantitative mixture until now impossible.

Another important point is to involve citizens in these processes. It requires to have a great knowledge of the communities that operate in a certain territory, i.e., to institutionalize citizenship in order to be able to communicate (through local associations or other entities). But also to motivate through transparency, sharing the process, from the technical documents to the online plenaries or the minutes of the sessions open to citizens.

The other fundamental issue is to translate the technical objectives of the participation process into a language that allows generating dialogue with citizens and does not exclude them due to the lack of knowledge. The methodologies of recording and capturing the information generated in the process have to allow, in turn, to convert the qualitative information given by citizens into objective data to inform the planning and, ultimately, to empower citizens to promote themselves other processes of diagnosis, action and evaluation. At the same time, it is key to define the limits of participation, so as not to generate frustration among the participants.

Finally, we must talk about the new participation formats through digital platforms that in the last mandate in Barcelona have taken a lot of strength. These platforms have reinforced processes that until now were marginal due to the difficulty in their management, giving them a new boost.

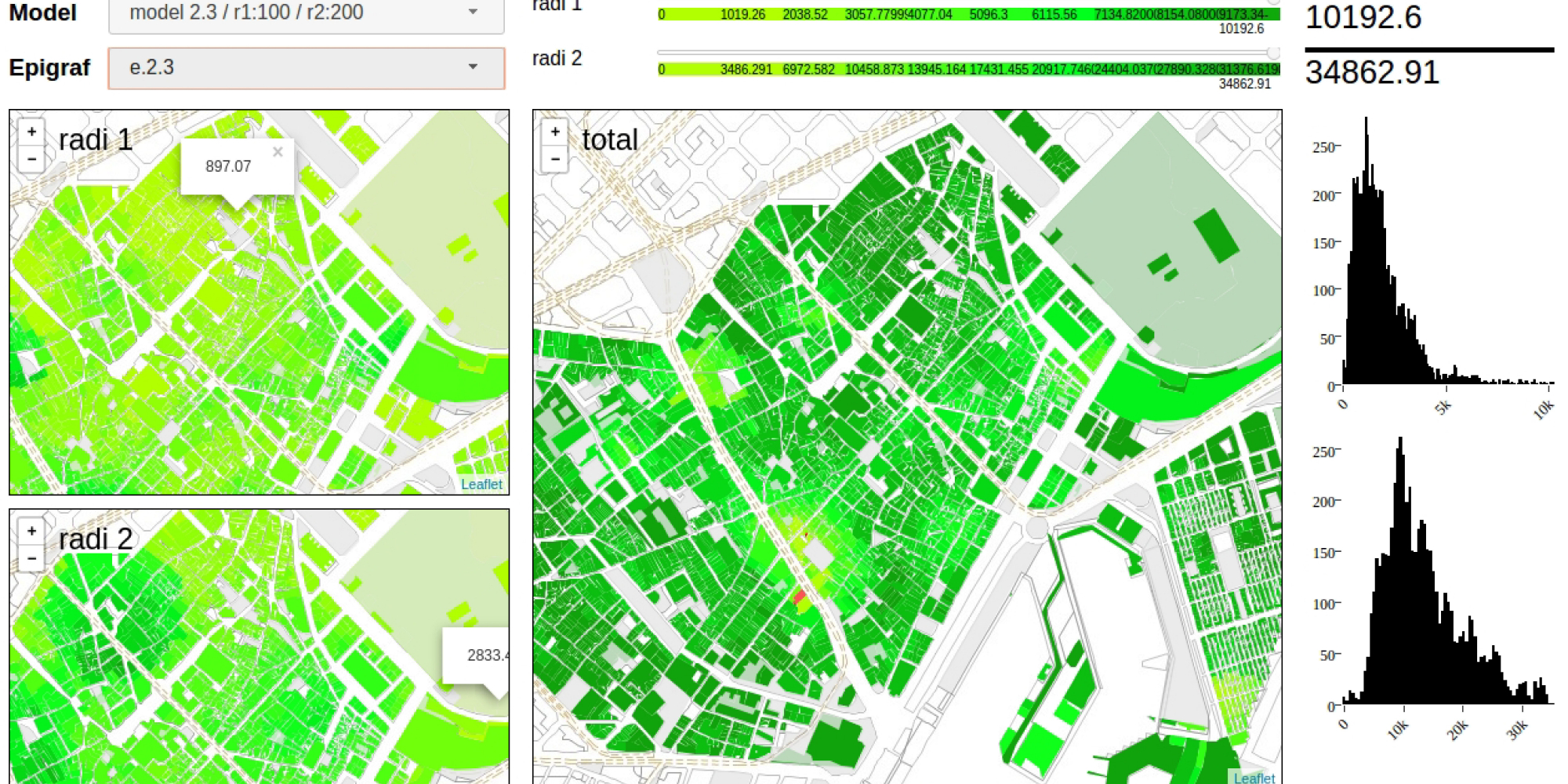

Simulation software: To model the application of parametres

Can you specify the share of artificial intelligence and machine learning within the project? How is it used? What is the outcome?

Mar Santamaria: Machine learning and artificial intelligence have been key in informing the land-use plan and its regulations and demonstrating the correlation between economic activity and impacts (thanks to multiple analyzes, causality occurs).

The drafting process started from a diagnosis with structured and unstructured data, which through multiple layers was intended to represent urban uses and conflicts arising in the district of Ciutat Vella. This means analysing and superimposing data from the population census, from the interactions of locals and tourists to social networks, from typologies and the influx to commercial premises, from noise sensors, among others, have been used. With this information, we have developed a complex model of the city to be able to predict conflicts and the resulting impacts.

This diagnosis gives rise to a system of rules that can be translated into objective parameters and that, through the analysis and modeling of current state, allows us to set a maximum threshold of economic activity that the urban fabric can absorb if we want to maintain the quality of life in the area. From here, we have generated simulations with infinite possible results. Learning from reality enable us to choose the most appropriate parameters, which end up being incorporated into the planning according to a city model to be preserved.

In short, working with machine learning and Al allows us to analyze, model, simulate and evaluate the result of the planning process.

What is your prediction for the future (about urban planning)?

Mar Santamaria: As we said before, we have to work with new scenarios of no growth, more knowledge of the existing city and, therefore, new data and tools that allow us to describe all urban phenomena together, generating shared proposals and evaluating their applicability. To sum up, we are heading towards a much more dynamic planning.

Pablo Martínez: But, above all, the future of planning happens to understand that the city is the game board of governance (which will be played more than ever in a local key). The large amounts of online services, the delocalised economic production and the intangible data resulting from the digital fingerprint become tangible in the urban space, that is, they manifest themselves in the form of new phenomena that have a physical impact on the habitability and quality of life of people. In this scenario, it will be necessary more than ever to establish new ways to regulate the urban space if we want to continue maintaining the social pact.

Interview with Francesca Bria and Şerife (Sherry) Wong, Jury members about the STARTS-PRIZE

300.000 Km/s is an urban innovation office based in Barcelona that explores the potentials of data and new computation paradigms to extract relevant information with the aim to improve urban planning and decision-making. Directed by Mar Santamaria Varas and Pablo Martinez Diez, our interdisciplinary team works in the fields of urban analysis, cartography, strategic planning, development of digital tools, and digital humanities. In the last five years, we have collaborated with public entities, international firms, cultural and scientific institutions and non-profit organizations.

Our projects have been recognized with various awards and mentions—among others BBVA-Civio Data Visualisation Award (2014), Open Data Institute Awards (2016), CityVis Prize (2017), Biennial Española de Urbanismo y Arquitectura (2018), and LLuís Carulla Award (2018)—and have been exhibited at the Biennale of Venice, the Chicago Arts Institute, the Center of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona, and Madrid CentroCentro, among others.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 732019. This publication (communication) reflects the views only of the author, and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.