The 2013 Ars Electronica Festival with its Total Recall theme provided a most appropriate setting for the premiere of MEGA – Museum of Electronic Games & Art’s “Ludic Memento” exhibition that not only takes a diversified approach to stimulating visitors’ recollections and reactivating nostalgic feelings but also demonstrates promising tactics for dealing with digital memory. Festivalgoers could proceed on their own to immerse themselves in four thematic domains or join a guided tour through the exhibits on display.

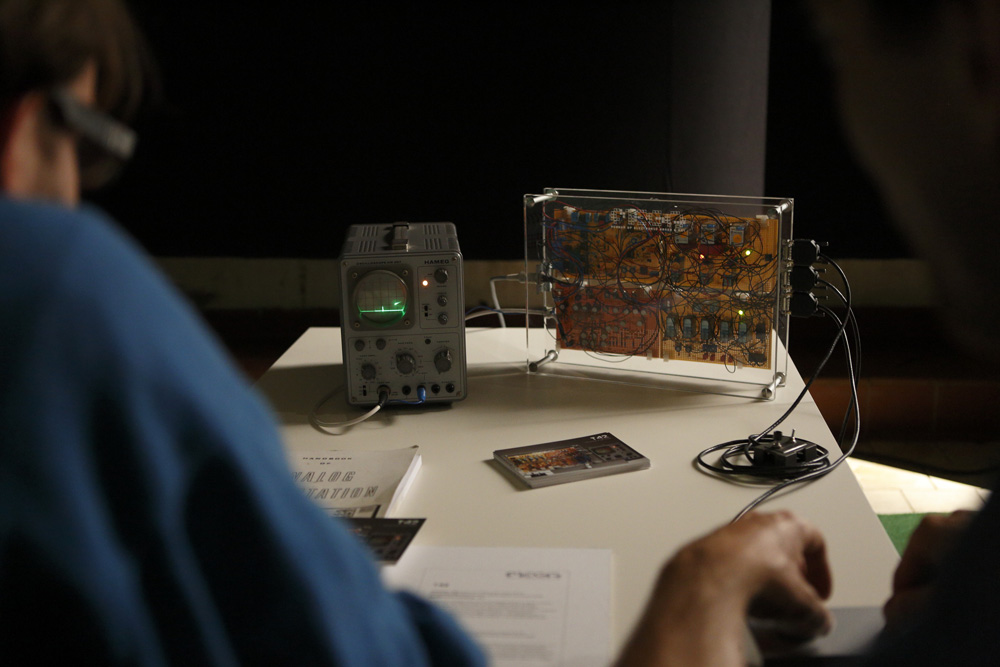

The first stop on this journey back in time was 1958: Tennis for Two, the first video game. It gets across the charm of the analog computer, a technology utterly forgotten today. The clicking and clacking of the relays are clearly audible during this match, and it does a great job realistically simulating the trajectory and bounce of the ball in real time.

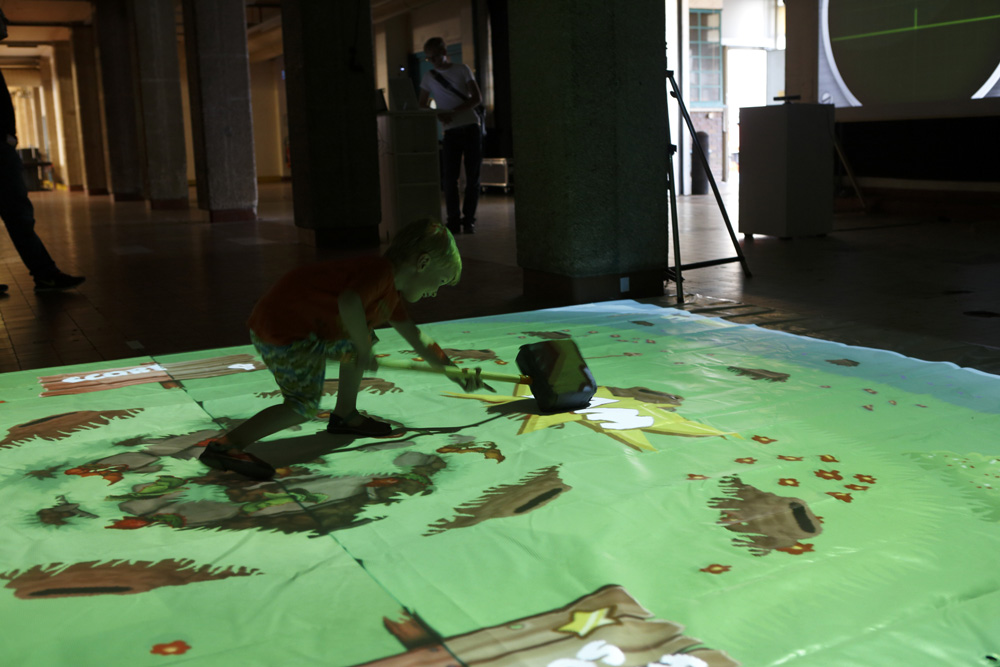

Across the way in the Tabakfabrik Linz’s generously proportioned exhibition space were the so-called re-mediations, meaning that historic games have been intentionally given a media makeover or reinterpreted. In going about this, prime emphasis is always on modifying the interaction. For instance, visitors can try out a Kinect version of Tennis for Two, and experience becoming the controller instead of having to hold one in your hands. Opposite this installation is a lineup including the complete series of Nintendo’s Game & Watch—aka tricOtronic in Austria—and three other re-mediations: Vermin, Ball und A Day of Ball. The 61 Game & Watch originals, fully functional and brilliantly staged, evoked a massive emotional outpouring. The juxtaposed re-mediations of Vermin—an installation created by students that was playable by means of two projectors on the floor and a real shovel—and Ball (re)acquainted visitors with the ingenious simplicity of these games and constituted a real highlight, especially for younger gamers.

In addition to the re-mediations, four screens presented familiar classics as emulators. The interaction was left unchanged but, due to the absence of the original data storage medium, users’ haptic experience was diminished or the quality of the sounds and graphics limited as a result of problems in emulator development. Nevertheless, these details are apparent only to experts.

Visitors interested in trying out the concept of a Digital Library came to the right place. Amidst four installations well-stocked with classics from the history of computer games was a podium at which visitors could query a MEGA expert about a game they fondly recalled from their younger days. The expert then located the game in the MEGA archive and transferred it onto the original data storage medium so that the visitor was able to play it on the original system.

This Digital Library was complemented by a Cartridge Library, an amazing installation in its own right that includes 200 long-obsolete data storage media. At the sight of so many modules and diskettes, some visitors felt like they had been teleported back into the early 1990s, and many were happy to re-encounter quaint media that had once been the state of the art. Some visitors inquired how it’s possible to access this content now, and were pleasantly surprised to find out that the data storage media on display still work. Just like the shoe carton full of photos taken on vacations decades ago, the brilliant colors may have faded after being in storage for so long, but the images have nevertheless been preserved. For example, even after 50 years, it’s still absolutely no problem to read out an Atari module.

The final stop on Ludic Memento’s itinerary through gaming history was the Digital Oblivion exhibit. A complex network of multiple antiquated processors generated an interconnected moving image screened on several monitors and portraying the history of the technological development of which they are a part—the earliest computers, the very first networks and mailboxes, the infancy of the internet with Mosaic browsers and Google Beta, and culminating in the present with error messages and servers of all shapes, sizes and providers going down. Digital Oblivion is a monument that shows how fragile, fleeting and aloof digital networks and cloud contents are.