Foto: Alan Puah

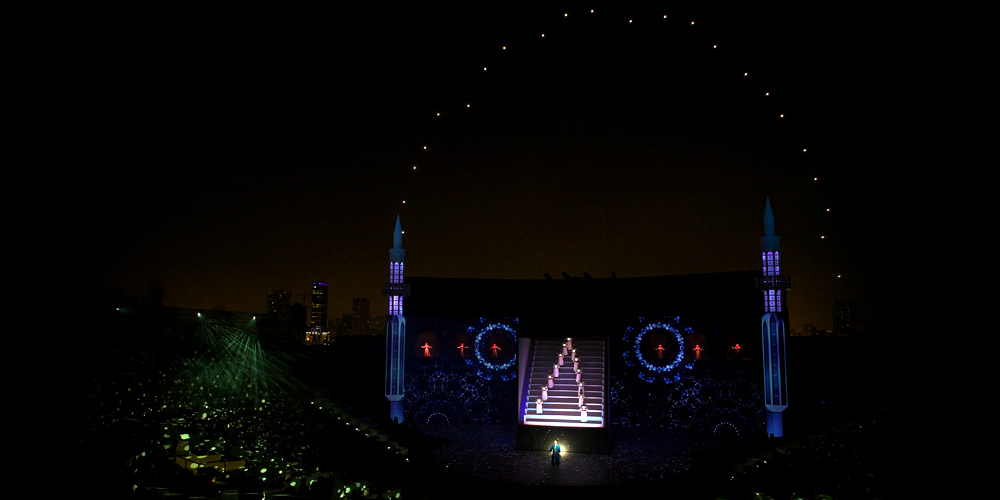

This show was a blockbuster hit. On an artificial island in the center of Sharjah, one of the seven emirates that make up the UAE, Sheik Sultan bin Ahmad Al Qasimi recently commissioned the construction of the Al Majaz Theatre, a Roman-style al-fresco amphitheater with a seating capacity of 4,500. This cultural center was completed right on time for March 26th, the day on which Sharjah began its term as 2014 Islamic Capital of Culture. “Clusters of Light” was designed as the huge opening ceremony featuring a narrative account of the life of the Prophet Mohammed and the early history of Islam that would be presented five times within the next three weeks. Among the stars of the “Clusters of Light” were the Ars Electronica Futurelab’s illuminated spaxels that lifted off for spectacular formation flights three times in each performance. We talked to crew member Chris Bruckmayr about how they prepared for an event of this magnitude and how things went …

How did you manage to land this commission?

Chris Bruckmayr: Once Sheik Sultan bin Ahmad Al Qasimi initiated the amphitheater’s construction, he decided to have a play by famous Arabian artist Abdul Rahman al-Ashmawi adapted to depict the life of the Prophet Mohammed as a sort of oratorio. However, due to religious considerations, the Prophet himself was not to be depicted. So that’s why he approached Multiple & Spinifex Group, an Australian firm that already had much experience with opening ceremonies at events like the Olympic Games in Beijing and Vancouver. Spinifex, in turn, had caught the online buzz about our spaxels shows. We were subsequently invited to take part and join a cast and crew totaling 750 people. Sheik Sultan bin Ahmad Al Qasimi originally wanted to stage a classic oratorio with actors, but they convinced him that gigantic projections and a Bollywood-like approach is far more emotional. He really liked the idea!

Photo: Sharjah Media Centre

What role did the spaxels actually play in “Clusters of Light”?

Chris Bruckmayr: While the cast—many of them top stars in the Arabic world—were acting out the narrative on stage, we were visualizing it aloft. In this spirit, we formed classic elements with the spaxels—an arc spanning the entire amphitheater, and the words of God that fell from the sky like drops of rain. For the first time, we worked only with a pure white color because it’s most appropriate to the religious theme. Our part was very elaborate since we had to fly three sequences within a single show—twice with 25 spaxels and once with 15. After the big VVIP Show attended by important figures from throughout the Arabian region, there were five sold-out performances, each before an audience of 4,500. So we had a lot to do. Our crew consisted of four people, and we worked on-site with the director to fine-tune the show. They asked us to make suggestions for formation flights, which we, in turn, adapted to their conceptions. Then we had some rehearsal flights, after which they sometimes even shorted their own scenes or adapted them to us.

In a situation like this, good preparation is definitely the sine qua non …

Chris Bruckmayr: Our simulations prepared us well for this assignment; however, a few adaptations had to be made and inserted into our show design because the physical setting was very complicated. The takeoff & landing area was minute, and we had to precisely conform to the timing of the show as a whole. Ultimately, audience security had highest priority, so we simply could not afford to make a mistake. It was stressful and thrilling at the same time—cause no damage to the equipment, zero personal injuries. We were really under intense pressure. This was a completely new experience for us, one that forced us to proceed with consummate professionalism. Between the spaxels’ first and second appearances, we had only 15 minutes to install fresh batteries, so we developed a formalized system to orchestrate the switch with commands issued via walkie-talkies. After three weeks, though, we had the routine down pat so the commands weren’t even necessary anymore. Then we had an hour between the spaxels’ second flight and their appearance in the grand finale, but the pressure remained very high, since we were constantly testing the spaxels to make sure that the rotors kicked in, the LED system was functional, and so forth.

The spaxels crew (from left to right): Benjamin Olsen, Martin Mörth, Patrick Müller, Andreas Jalsovec, Chris Bruckmayr, Michael Mayr, Michael Platz, Photo: Martin Hieslmair

How much latitude did the spaxels crew have during the show?

Chris Bruckmayr: We had a preset routine. All the pre-flight checks were completed 10 minutes prior to scheduled takeoff and the spaxels were turned on. Then, all we had to do was pay attention to the time code while we were in radio contact with the stage director. Here, our takeoff was timed to the second. This was the outcome of a very complex computation: How long do the spaxels need for the actual takeoff? How long do they need to get into formation once they’re aloft? How long do they need to fly the 100 meters to the amphitheater itself? And at what exact point in the flight do the LED sequences have to be activated so they’re synchronized with what’s happening in the show as a whole? But because the amphitheater is surrounded by high-rises, we had some GPS signal problems at times. When the reflections are very strong, then the spaxels get oriented on a totally erroneous location, and that becomes a problem on the return flight because they try to land at a spot that they wrongly consider to be the one they took off from. In response, we brought out an old routine from our bag of tricks. Now, the spaxels have a low-level and a high-level processor—the former controls only the automatic flight behavior in the air, and the latter is for the GPS processing and the LED animation. So then, we took off using only the low-level processor until the GPS signal improved and we switched over to take advantage of the system’s entire processing capacity. Sometimes, we even took individual spaxels in our hands and held them up! For normal shows, we start to rehearse three days in advance, but here we were already on site 10 days before the premiere. Nevertheless, changes were constantly being made to the show over the course of the rehearsals. Everything we learned there, we adapted ourselves.

Photo: Alan Puah

In February, the spaxels flew in sub-arctic conditions at the opening of the European Capital of Culture in Umea, Sweden. Next up was Sharjah, this year’s Islamic Capital of Culture …

Chris Bruckmayr: The temperature difference was enormous. In Sharjah, it was between 25° and 35° Celsius. On the hottest day, we had to deal with a technical problem: the surface temperature on the airfield was over 50°. Nevertheless, we still had to fly, though none of us had a good feeling about it. But then came a two-day rainstorm, which is quite unusual for that time of year, and the VVIP Show had to be postponed a few days until the weather cleared up. We took advantage of the delay to conduct additional tests, since it didn’t rain constantly. There were also periods with gusty winds, another challenge for formation flying. And there was also an incredible amount of sand in the air; extreme heat with sand and wind. In any case, now we know that the spaxels can fly almost daily over three weeks even when it’s very hot. But, of course, we’ll have to check everything again before the next show. Now, the only thing left is a jungle! [laughs]

How did the spaxels get from Linz to the UAE?

Chris Bruckmayr: Usually, in conjunction with a spaxels flight, we organize the logistics ourselves, but in this case Multiple & Spinifex Group’s transport agency handled it. Before we packed the quadcopters according to the tried-and-true system we’ve developed, we fully tested all of them. A week later, the spaxels were delivered intact right to our airfield in Sharjah. But then, before the first test flights, there was still a lot to do. Of course, we had to retest all the spaxels, since you never know what happened in transit. We needed three days until we were really ready for formation flying.

And a swarm of this size needs a correspondingly large takeoff & landing area …

Chris Bruckmayr: Yeah, we need an airfield with a structure where the spaxels can be arranged in formation with a prescribed distance between each one. And this is impossible without a structured airfield. Of course, our fantasy would be to drive an 18-wheel semi, open the roof of the trailer and the spaxels fly out! But we’ve learned that we can make the airfield smaller and smaller. Then again, we could take off in small groups, which would require even less space. That would be an option. But generally speaking, the airfield is important because GPS-controlled spaxels never return to the precise spot they took off from. You need a certain amount of leeway for the landing. Occasionally, we even have to catch them in midair to prevent them from splashing down if there’s any water next to the airfield—like there is here.

How many spaxels can take off at the same time?

Chris Bruckmayr: Theoretically, at least 100 spaxels can start simultaneously, maybe even 200. But doing it would be a major production—the airfield would have to be much bigger; we’d need more assistants; the logistics would be on a more massive scale. For our relatively small crew, assignments like this would also call for quite a bit of preparatory work. And you also have to take into account refitting the quadcopters, which are manufactured by Ascending Technologies. Even a test of this magnitude isn’t simple. And you always have to consider local air traffic regulations.

Photo: Ars Electronica Futurelab

What are some other ways the spaxels could be improved?

Chris Bruckmayr: Just recently, we conducted high speed tests with the spaxels as part of an effort to make the formations even more dynamic. Their horizontal speed is a lot faster than we thought, and also much higher than the manufacturer’s recommendation. This is an ongoing R&D project, since this would also expand our show design possibilities. After all, faster spaxels make for more fascinating formations. As far as brightness is concerned, we’re at a satisfactory level. We’ll slim down the LED module a bit but it doesn’t need to be any brighter at the moment. We can display all RGB colors and adjust the intensity. It would hardly be possible to eliminate any more weight, since the battery is the major factor here and development in this area is proceeding very slowly. As a result, the show design constantly has to take into account the length of time between a landing and the next takeoff so the crew has time to swap batteries. Unfortunately, we’re unable to fly longer than 10 minutes at present.

We learn from every show; learning by doing is our motto. We do R&D on site because we need it on the spot.

Are you planning more shows of this magnitude?

Chris Bruckmayr: Yes, I’m totally sure about that. Our performance was a resounding success. The feedback we’re getting has been fabulous! It’s very likely that we’ll be part of the next open-air theatrical production of this kind. The Multiple & Spinifex Group wants to continue working with us. So, we’ve got our foot in the door in this very financially rewarding area, and now we’ll see how it goes from here. They already told us in Umea: Once you’ve taken to the sky, everything else is no big deal. Over and over again, it’s totally amazing to see how people react to the spaxels’ formation flights. Of course, with large-scale projects like this, the expectations get higher and higher. We’ve now reached a semi-Olympic level.

Additional impressions and information about the spaxels are available at ars.electronica.art/futurelab