This is Round 7 of TIME OUT, an exhibition series offering visitors to the Ars Electronica Center insightful looks at work being done by undergraduates in the Time-based and Interactive Media program at Linz Art University. This show was once again curated by Gerhard Funk, the director of the program, and Gerfried Stocker, artistic director of Ars Electronica. They selected nine students, who have personally installed their works in the Ars Electronica Center and will present them at the premiere on May 23rd.

Sarah Hiebl’s work entitled “How to Infiltrate a Group of Friends” is an autobiographical computer game meant as a means of dealing with lost friendships. There was no argument or identifiable provocation—nevertheless, a group of friends went their separate ways. The game was an attempt to discover the grounds, and culminated in acceptance of the situation. Sarah Hiebl’s bachelor’s degree project is an autobiographical process of coming to terms with what happened. It includes psychoanalytical aspects, and is structured like a whodunit. Players click their way through the game and have to make decisions—none of which are automatically deemed to be right or wrong. We asked Sarah to tell us more about her very personal work.

A Scene from Sarah Hiebl’s “How to Infiltrate a Group of Friends”. Credit: Sarah Hiebl

Sarah, you call your computer game autobiographical. Who vanished from your life?

Sarah Hiebl: When I moved here, I made friends with several people at Linz Art University. We were inseparable for a while, and did all kinds of stuff together. It was a truly delightful experience every time we got together. And then suddenly, we stopped meeting regularly. At some point, they were gone and I didn’t know why.

How did this personal experience turn into a detective game? Could you go into more detail about how your work came about?

Sarah Hiebl: Originally, I wanted to create a game about these people to show them how important they are to me. When I got started working on it, I wrote down all the moments we shared, and I tried to somehow comprehend these people in order to create a game for them that really shows how wonderful they are. While I was working on it, our contacts became less and less frequent, and instead of taking with me the pleasant memories of the good times we had, I started dissecting the whole experience. Could I have done something better to prevent this break-up from occurring? The weird thing was that there hadn’t been some big argument; there was no real reason why we grew apart. It simply happened. The game progressively developed along with me. And by the end, the work also enabled me to understand that this is just the way it goes—not everything endures forever and there are some things you just can’t control.

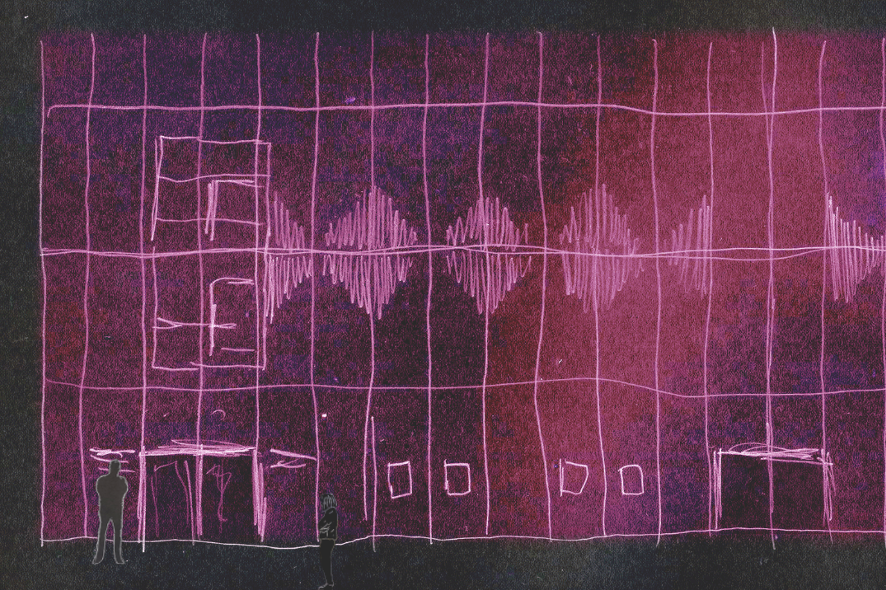

Sketch-like hand drawings emphasize the atmosphere in “How to Infiltrate a Group of Friends”. Credit: Sarah Hiebl

Most of your games are based on very artistic drawings done by hand. What is it about this that you like so much?

Sarah Hiebl: In my games, I always film myself first and then I trace my movements by hand. That way, my game is endowed with even more of my own personality. I also like to make the graphics fluttery and rather finely rendered. After all, most of my games have to do with memories, and they’re simply not high quality graphics; they’re rather jumpy and blurred.

How do you develop new project ideas? What are you inspired by in your work?

Sarah Hiebl: My work is always inspired by real events. I’m not good at expressing myself like a normal person, which is why I use my games to make my experiences comprehensible. It’s a very beautiful and moving feeling for me to consider how many people have come to me and said that they’ve recognized themselves in my works. In them, I process fragments of myself. I have a tremendous need to communicate and, of course, I also want to be understood. My games make this possible.

Artist Marlene Reischl in front of her interactive installation “All of Us”. Credit: Martin Hieslmair

“All of Us” by Marlene Reischl confronts the aesthetics of scars. We all have scars. No two are alike and each one is associated with a story of greater or lesser proportions. In Reischl’s interactive installation, each visitor’s body is scanned by a camera system. Their touching of their body with one of their hands triggers the playback of macro-videos of scars at that same location on the body. Interlinking the installation visitor’s act of touching his/her own body with the subsequent selection of the video to be screened engenders an intimate, almost contemplative action. We talked to Marlene about this.

Your installation is very intimate and, for those beholding it, possibly unpleasant or associated with painful memories. Is that intentional?

Marlene Reischl: No. The idea wasn’t to dredge up negative associations, but rather to bring out the scars’ visual qualities.

How do visitors react to experiencing your installation?

Marlene Reischl: What initially predominates is the playful aspect, whereby visitors learn to interact with the installation. Thereafter, I’m often able to observe a mixture of intimacy and curiosity as people begin to touch their own body in order to view more scars on screen.

Marlene Reischl. Credit: Martin Hieslmair

What led you to choose scars as the theme of your current work?

Marlene Reischl: I wanted to showcase scars without the cheap sensationalism. What fascinates me about this is taking something that’s often hidden and making it visible. The interactive components weren’t added until later.

Where did you get all the videos showing scars on the various parts of the body?

Marlene Reischl: At first from my circle of friends and acquaintances, who, in turn, told others among their friends and acquaintances. Since then, I’ve even been contacted by complete strangers who’d like to be a part of my work. It’s important for me to let the “show people” view the footage I’m shooting while it’s being shot. Many people were initially skeptical, but became more open once they realized how the scars are being depicted.

So, anyone who has a scar and is interested in participating can get in touch with you?

Marlene Reischl: Sure, I’m still filming on a regular basis to increase my stock of material. Anyone who’s interested can send an e-mail to allofus@marlenereischl.com.

A visitor watches the video of a scared scalp by touching her own head. Credit: Robert Bauernhansl

The TIME OUT .07 exhibition opens on May 23, 2017. Visitors can view these works by student at any time during the museum’s opening hours.