Rachel Hanlon’s interest in pop-culture, film, music and autobiographies add layers of depth to references in her works that use media appropriation as central themes. Hanlon’s present research forms part of her PhD, for which she was awarded a full research scholarship to complete from Deakin University, Australia. The Hello Machine is an installation connecting the Ars Electronica Festival Linz, Science Gallery Dublin and Volkswagen Berlins Drive Exhibition, has been developed with the assistance of the Ars Electronica FutureLab, by way of vintage or obsolete pay phones from Hanlon’s collection. The Hello Machine’s ‘Hello Machine – Hello Human’ feature touches on the playful moments that are shared between man and machine. They provide a way in which the viewer can interact with re-animated technically obsolete telephone systems, utilising present day advancements in telephony. When you use a Hello Machine who will you talk to, a machine or a human? What are you hoping for?

An obsolete pay phone of the Austrian Post is waiting for its users at the entrance of the Ars Electronica Festival for a conversation with somebody or something. Credit: Rachel Hanlon

How did you develop the idea of an installation which uses vintage technology items to make us aware of their sentimental meaning besides its function?

Rachel Hanlon: My attraction to objects of the past, the people who used them, and the autobiographical narrative contained within our shared histories with them, drives me to continually question what elements come into play while exploring why certain objects matter to us. What I like is that objects tend to have the residue of ‘life lived’ upon them; their ‘skins’ are marked and worn with our touch. Junichiro Tanizaki (In Praise of Shadows, 1977) expresses it well stating that objects aged by use ‘call to mind the past that made them’. Through my process of trying to find answers to these questions for myself, I begin to think of how objects from the past can become the metaphorical building blocks of catalogued emotion and expression for us. For ‘us’, the generations born forth from the industrial revolution, technology has played an integral role in our lives as objects of fascination and reliance. Because of this I feel there is a need to explore and reflect upon what these objects mean to us to provide an insight for future generations. This in turn also provides us with an ability to better understand and relate to future technologies, with the ability to acknowledge the meaningful affections we are yet to develop for them.

“Objects of the past contain an autobiographical narrative contained within our shared histories.” (Rachel Hanlon, Researcher&Artist at Ars Electronica Futurelab)

More than 50 years ago, one was having a clear picture of the operator who was on the other end of the line. Those pre-conceptions have disappeared in the modern times. Credit: envisioningtheamericandream.com provided by Rachel Hanlon

There is a notion of object-driven self-identification involved, isn’t it?

Rachel Hanlon: The research around and related to the ‘thingness of things’, relating to Martin Heidegger‘s notion of ‘thingness’ as being when an object comes into ‘presence’, a particular way of ‘being’ in the world, has become a driving factor within my process. This has led me to investigate how the obsolescence of a technological device (an object) can possess a presence and power to engage with a viewer and how this can be conveyed, opening up a dialogue between their ideas and meanings, what makes up the ‘thingness’ these objects possess. Bruno Latour states that ‘things do not exist without being full of people’. Technological objects that are obsolete or reaching obsolescence seem to be, for most, devoid of people, discarded and dusty with the absence of their touch. I like to reanimate the objects in some way, showing people that these things are very much still full of people, full of us. I hope by working with old technologies I can expose and release the layered meanings for the viewer, by unravelling their historical and societal content that contains important traces of our identity.

Why did you use the telephone as the technological device of interest? It is still a used object though smartphones outdo them in terms of use!

Rachel Hanlon: My original interest in exploring our relationship to telephones was ignited by a blue payphone situated in an Australian Hospital that I saw each day during my comings and goings for a month that I visited my father while he was ill there. This phone, which seemed to just blend into the herd of unused machines dotted about the corridors, did not figure into my consciousness as a ‘thing’ to be concerned with until I noticed that someone had added in red pen across the ‘out of order’ sign ‘since 2009’. This comment not only humoured me, it got me thinking about why did I not really notice or care about the phone until I saw the witty reference to its demise… what had made me suddenly see this ‘object’ as a ‘thing’…? It simply was the fact that something broke through my consciousness to trigger me to reminisce about my own use of telephone, and with this, also pay phones. The telephone ‘pay phone’ booth has gone through many changes during its lifetime, and at present it often stands alone, unused and unnoticed. Gone are the impatience lines of callers waiting for their turn, this visual is now more familiar to younger generations only in films. As a part of my continuing research, I have been collecting vintage payphones from different countries while travelling to consider their similarities and differences, which has also lead to many people sharing their stories of use with these devices.

The initial spark for the “Hello Machine” came with the sight of an obsolete pay phone at an Australian hospital. Credit: Rachel Hanlon

The telephone ‘pay phone’ booth has gone through many changes during its lifetime, and at present it often stands alone, unused and unnoticed. Gone are the impatience lines of callers waiting for their turn, this visual is now more familiar to younger generations only in films. As a part of my continuing research, I have been collecting vintage payphones from different countries while travelling to consider their similarities and differences, which has also lead to many people sharing their stories of use with these devices.

And how do you bridge that nostalgia to the present in your “Hello Machine”?

Rachel Hanlon: At present I am particularly interested in the way that things can give testimony to who we are at a given time. How can notions of nostalgia, collective memory and artistic speculation be understood when viewing the previous functionality of objects and inflected by artistic curation and modification? For this project, to explore the ‘thingness’ of the payphone/telephone for myself, I needed to couple it with the personal and collective memory of the values and experiences attached to those uses of others, not just myself. I see the telephone as having a ‘cultural and functional hybridity’, for it exists as a functional technological object, but also becomes a ‘cultural object’ through its use within the narrative in film, and its influence on our ways of communally communicating as a society.

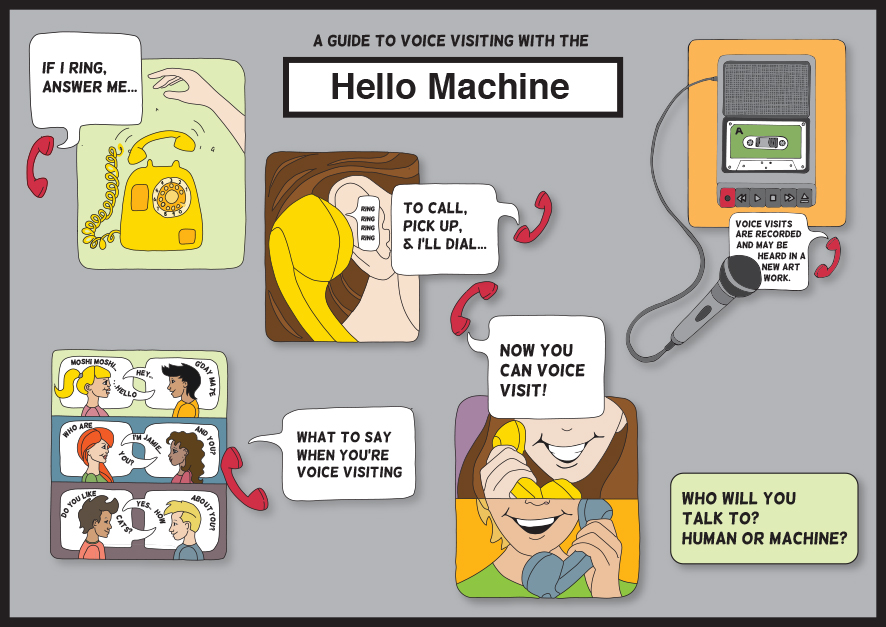

The workings of “Hello Machine” explained via graphics. Credit: Rachel Hanlon

When technologies reach obsolescence, our relationship with them changes, but what never changes is our need to reach out to others, connect and share. But what if no one is on the other end of the line? Who is there to hear us? AI has made sure there always is! A ‘speech race’ is upon us, first we had interactive voice response systems, now with natural language interface systems we have our new ‘weavers of speech’, these modern day ‘voices with a smile’ are changing the way we communicate with our phones. Siri, Alexa, Bibxy, Cortana and Google Assistant (shall we call her Gabby?) are all vying for your attention, but what will our budding relationships to these Boy/Girl Fridays blossom into? With future developments in AI, and the possibility of ‘machine learning’, will it be a version of Samantha, Her (2013), or a version of HAL 9000, A Space Odyssey (1968)? Some of the greatest minds today are joining together to limit the possibility of an eventual Skynet, (Terminator franchise) developing. While we in the now wait for the history of the future let us know what happens, we have fun with our ‘Siris’ and they humorously, and often fumblingly, play along with us, giving us more the reality of Holly from Read Dwarf. In the end, maybe they will end up being like Deep Thought from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979), and answers the most important questions in life for us. A Hello Machine, when no human is present on the other end of the line, seeks to connect with you by flipping this concept around, asking what can you do for her. Once a technology or practice evolves or becomes obsolete, what is made obsolete is a set of relationships, values and the meanings they bind together. Concerning the relationship between man and machine, I think how we have fun with and explore new technologies can be made richer through our acknowledgment of our relationships with past technologies that have developed along beside us and because of us. I hope that connecting to someone, human or machine, through a Hello Machine, people can once again feel the trepidation and excitement of wondering who is on the other end of the line.

Rachel Hanlon is an emerging artist in the field of media archaeology. Her works make available many layered metaphors and meanings through reinterpretations of obsolete technologies that are heightened by our cultural reliance on them as a part of the narrative of our times. Hanlon’s interest in the re-articulation and appropriation of found materials, explored through creative art practices, reveal and inform the way the complexities of past and present are understood and experienced.