This question marks the beginning of the project LABOR, for which Paul Vanouse was awarded with the Golden Nica in the category Artificial Intelligence & Life Art of Prix Ars Electronica. In their statement, the jury praised the elegant way in which he combines “reflections on the automation of work and the obsession with optimization in the name of capital, current challenges of today’s microbial research with regard to the concept of human individuality and the progressive disappearance of work and workers as we know them”. We asked the artist and researcher how sweat and work are connected, what makes people human, and he explained what caused the term “sweatshop”.

Could you please explain how sweating and developing a certain smell work in the human body?

Paul Vanouse: Humans sweat primarily to regulate temperature—as the sweat evaporates, the body cools. Sweating is also triggered by emotional stresses. The former sweat is produced primarily by the eccrine glands distributed across the human body, whereas the latter, is produced mostly by apocrine glands in areas such as the armpit as well as genital areas and other moist regions of the human body. Humans are pretty distinct from other animals in terms of how this all works, since most animals don’t cool their bodies in the same ways.

All sweat is nearly odorless liquid containing minerals and some urea, though apocrine sweat also contains fats, proteins and hormones. The scent of our sweat comes when it is metabolized by bacteria living in and on our bodies. Different bacteria use different metabolic pathways to digest our excreted nutrients, which produces different smelly bi-products.

Three bacterial strains have been identified as keys to the production of human scent, from the genera Staphylococcus, Propionibacterium and Corynebacterium. Staphylococcus species metabolize skin secretions into compounds such as isovaleric acid, to produce a fairly mild scent and are associated with the eccrine sweat glands, which excrete primarily salts and water to regulate body temperature. Humans’ ability to distinguish this “high-pitched” scent has been found to vary by as much as one hundred-fold between individuals. Propionibacterium species metabolize more complex excretions from the apocrine glands and are responsible for vinegary, acrid odors, particularly under anaerobic conditions. Corynebacterium break down the lipids in sweat to create smaller volatile molecules like butyric acid. However, all these microbes act in complex, communalistic ways on the human body and utilize varied metabolic pathways to produce an aromatic bouquet of a complexity far greater than the sum of their parts.

…and how does “sweating” work within your project?

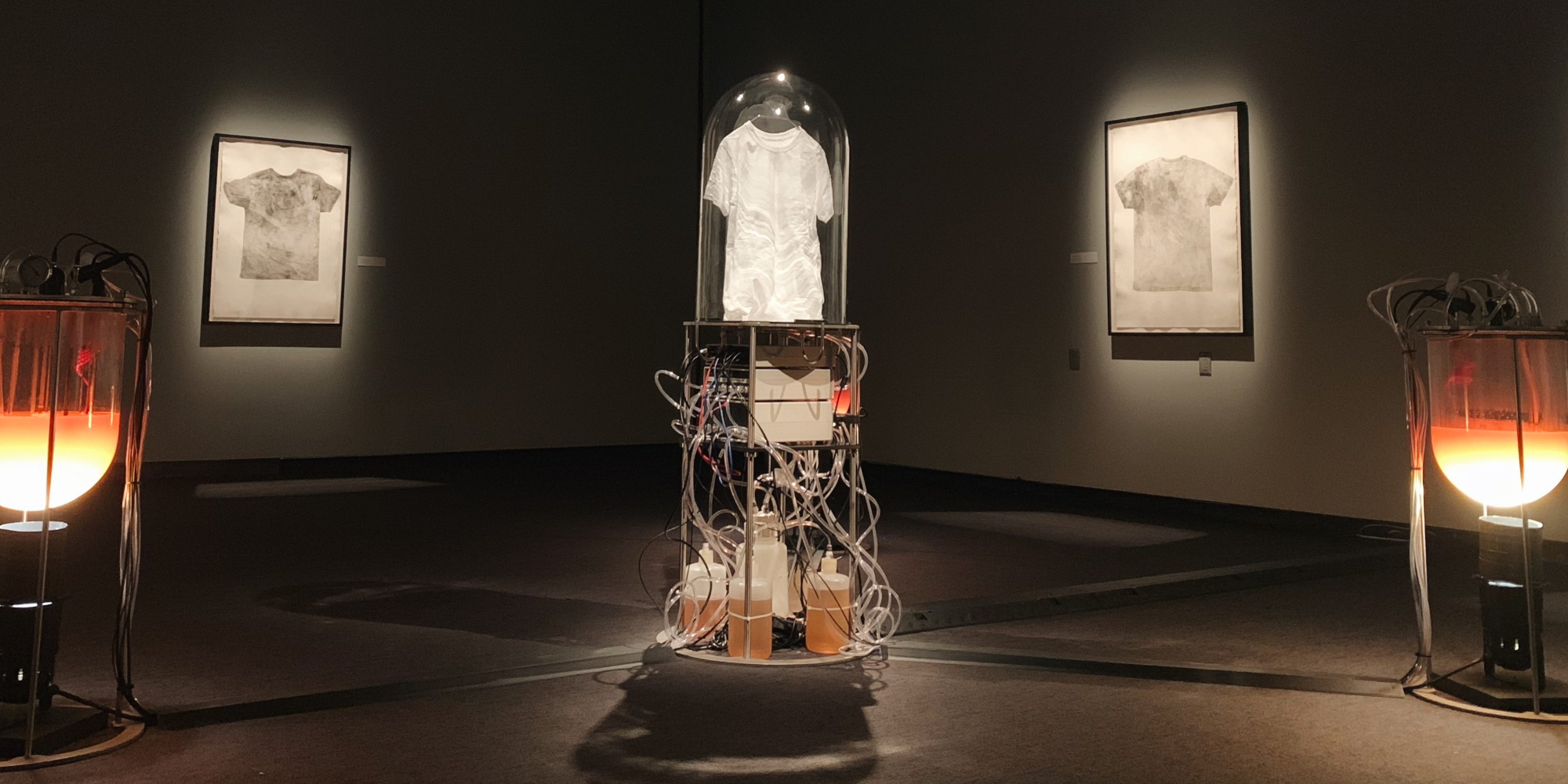

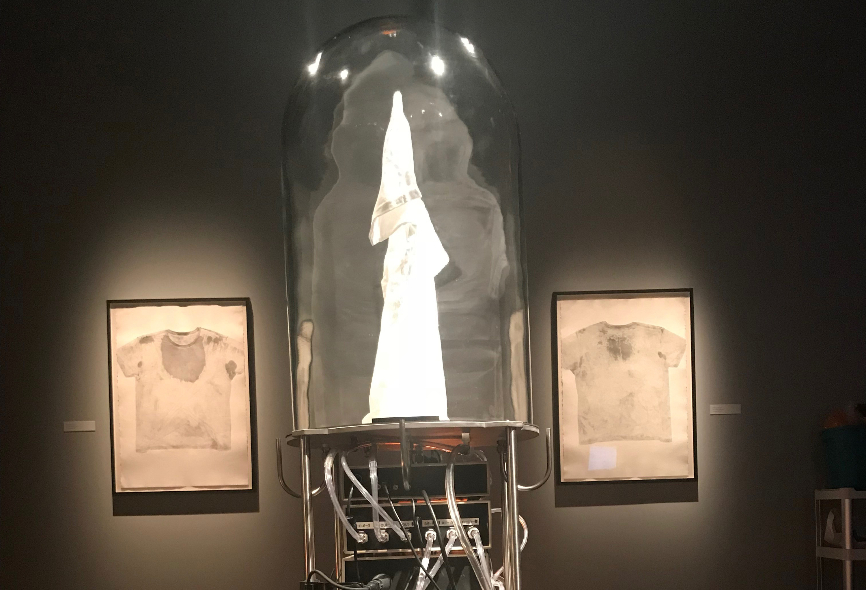

Paul Vanouse: LABOR is an art installation that re-creates the scent of people exerting themselves under stressful conditions—like in a factory. In LABOR, I incubate three species of human skin bacteria responsible for the primary scent of sweating bodies: Staphylococcus epidermidis, Corynebacterium xerosis and Propionibacterium avidum in large bioreactors containing about 20 Liters of nutrient mixture. They produce a semblance of the scent of human sweat, but without the actual human. The human is conspicuously absent in this phenomenon.

What is the connection between humans and bacteria?

Paul Vanouse: In the human body, bacterial cells far outnumber human cells. Bacteria not only inhabit us, but they define us. The distinctive scent that differentiates humans not just from other animals, but from other humans as well stems from the distinctive bacterial communities in and on our bodies.

In the age of post-industrialization, what significance does labor still have?

Paul Vanouse: There are multiple answers to this. Labor is still being performed in all types of both material and dematerialized ways, but in my work, I’m noting that material labor is increasingly carried out by non-humans (microbial production of medicines, foodstuffs, building and packaging materials, and other biotechnologies). And this is where a vast cascade of ironies begin to flow: the term “sweatshop” exists because the deep relationship between human labor and the process and scent of sweat, indeed, other animals laboring cannot produce this odor. Terms like “manufacturing” stem from “man” as well as “mano/main” or “hand”, human things, yet increasingly this has been performed by machines and non-humans. Formerly the scent of (even eccrine) sweat was crude because physical labor was not a high-status occupation, whereas nowadays it is increasingly even fetishized (in the US, the middle and upper classes increasingly go to exercise clubs to sweat in public). Thus, in the Labor installation, the scent of Labor is not produced as an unwanted “bi-product”, but as an “end-product” of this manufacturing activity. All has come full-circle.

In your video, you mention one of the big questions of our society: “Who is considered a person and when?” From your point of view, which answer is possible?

Paul Vanouse: I’m getting at the expansion of subjectivity in general that has been a basis for the evolution of human rights and the capacity of a dominant discursive group to acknowledge a subject position for “the other”. Increased understanding of microbes’ roles in our bodies has furthered a “post-human” understanding that somewhat dethrones all of us humans from a special subject position relative to other living things, the idea of personhood is expanding, but also perhaps weakening.

The winners of the Prix Ars Electronica will be coming to Linz for the Ars Electronica Festival, which will take place from September 5 to 9. In the Prix Forum they will discuss their works and dare a look into the future, their artworks will be on display in the CyberArts exhibition at the OK.

Paul Vanouse (US) is an artist and professor of Art at the University at Buffalo, NY, where he is the founding director of the Coalesce Center for Biological Art. Interdisciplinarity and impassioned amateurism guide his art practice. His bio-media and interactive cinema projects have been exhibited in over 25 countries and widely across the US. Recent solo exhibitions include: Burchfield-Penny Gallery in Buffalo (2019), Esther Klein Gallery in Philadelphia (2016), Beall Center at UC Irvine (2013), Muffathalle in Munich (2012), Schering Foundation in Berlin (2011), and Kapelica Gallery in Ljubljana (2011). Other venues have included Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, New Museum in New York, Museo Nacional in Buenos Aires, Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, ZKM in Karlsrhue, and Albright-Knox in Buffalo. Vanouse’s work has been funded by Renew Media/Rockefeller Foundation, Creative Capital Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, New York State Council on the Arts, New York Foundation for the Arts, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, Sun Microsystems, and the National Science Foundation. He has received awards at festivals including Prix ARS Electronica in Linz, Austria (2010, 2017) and Vida, Art and Artificial Life competition in Madrid, Spain (2002, 2011). He has an MFA from Carnegie Mellon University.