In the new exhibition “Me and the Machines” at the Ars Electronica Center, which is being staged in cooperation with the Robopsychology Lab at Johannes Kepler University Linz, human relationships with artificial intelligence and robotics will be examined in greater detail and the question will be asked as to how we as humans experience intelligent machines and how we behave toward them.

Based on changing works curated by the scientific team of the Robopsychology Lab, the new exhibition invites visitors to explore, try out and reflect. Questions explored together with the audience address aspects such as trust and understanding, rejection and acceptance, humanization of machines and dissociation from them.

Artificial intelligence, smart apps and robots become ubiquitous interaction partners. We take their recommendations, make decisions together, collaborate in the workplace, and talk to them – sometimes almost as if they were real people. But what are these machines to us, how do we, as human individuals with all our different needs and experiences, experience them? Are they welcome support or scary competition for us, mere tools or social counterparts?

Human thinking, feeling and behavior – these have always been central objects of psychology. Building on this, the Robopsychology Lab at Johannes Kepler University Linz has been researching since 2018 how people experience intelligent machines, how they behave towards them, and how needs of different groups of people are taken into account in technology development. Participatory and transdisciplinary research processes are of great importance here.

We spoke with Univ.-Prof.in Dr.in Martina Mara, head of the Robopsychology Lab at Johannes Kepler University Linz, about the new exhibition at the Ars Electronica Center.

There is already a long-standing relationship between the Robopsychology Lab and the Ars Electronica Center. Why is a museum a good environment for a research scenario?

Martina Mara: I am convinced that the research and development of new technologies must open up more to the broader society and become more participatory than has been the case to date. If the needs and perspectives of many different people – for example, with different ages, genders or backgrounds – are incorporated into research and technology design at an early stage, I hope that our gadgets of tomorrow will also function better for the heterogeneous groups of users that always exist in reality.

At the Ars Electronica Center, we reach a really broad audience with our research: schoolchildren, senior citizens, artists, tech experts and many more. At Me and the Machines, they can all put their personal relationship to robots and AI systems to the test and participate in on-site studies. The fact that the Robopsychology Lab has this satellite in the Ars Electronica Center is a great privilege for us!

The new exhibition explores how people experience intelligent machines. What are the experiences in this regard so far?

Martina Mara: So of course I have to answer: It depends. It depends on the type of machine, it depends on the context of use, it depends on the individual. For example, it makes a difference whether a user considers herself competent and self-confident in the field of technology or whether, conversely, she has the feeling that she no longer knows her way around all the hype surrounding AI and robotics and is then rather unsettled when she encounters a robot.

The way machine intelligence is reported in the media public also has an impact on our experience. An analysis by the Robopsychology Lab has shown that artificial intelligence is often portrayed in media images as highly human-like robots. I fear that such images lead to a strong overestimation of what is technically feasible or else trigger fears of the substitutability of humans.

At the same time, these depictions are surreal, because most of today’s “intelligent machines” don’t exactly walk around on two legs; instead, as we’re also showing in Me and the Machines, they’re either disembodied algorithms or very specialized, mechanical-looking robots of the kind we’re familiar with from industry.

By the way: We’ve also been researching the perception of industrial robots together with the Ars Electronica Futurelab for some time now. In our interdisciplinary research project CoBot Studio, we recently implemented a unique mixed reality game in Deep Space 8K in which participants had to complete tasks together with a physically present mobile robot in a virtual 3D environment. In Me and the Machines, we will be able to play back the results to the museum audience.

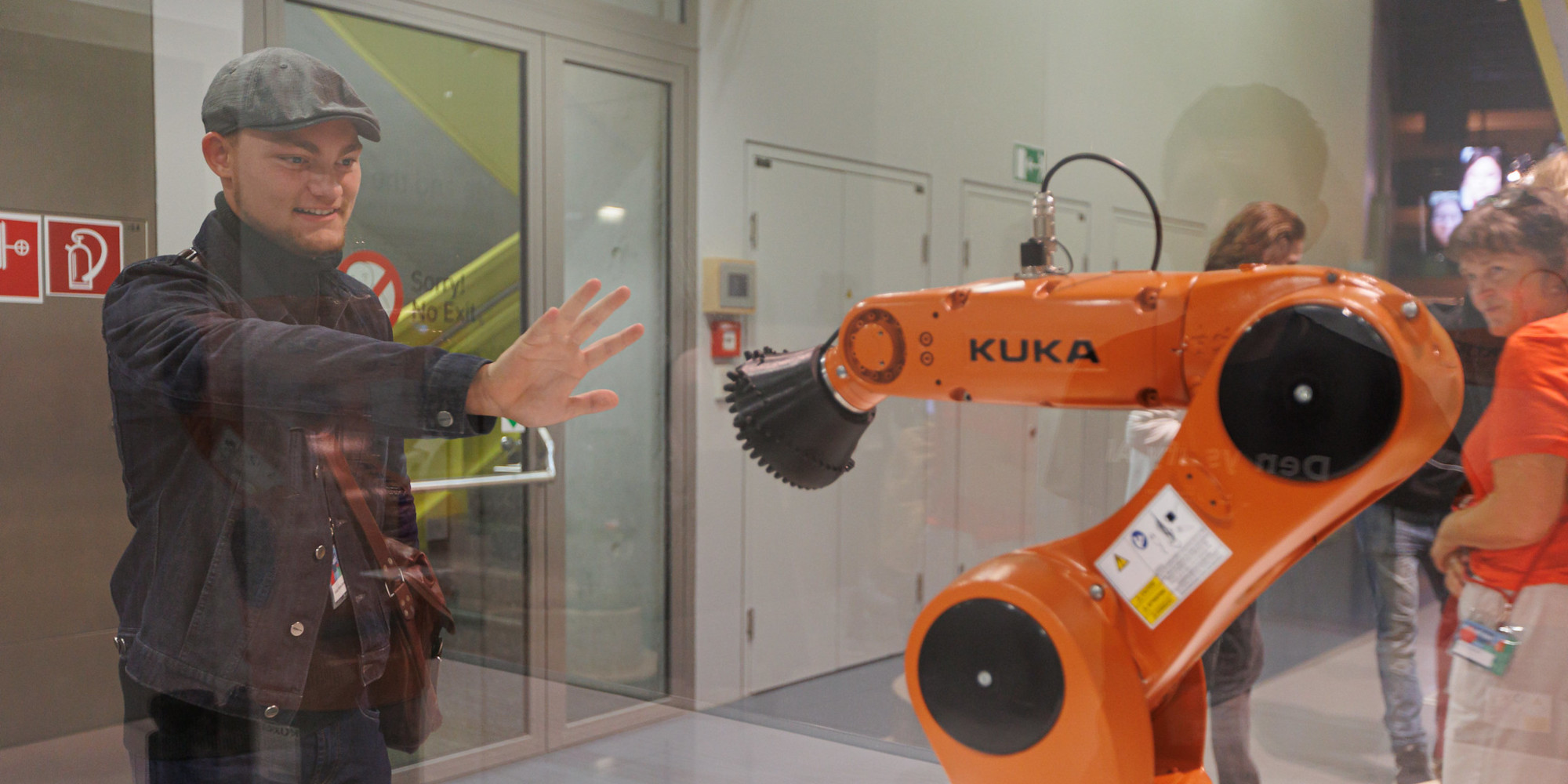

At Contact, a first physical contact with a KUKA robot can be established. What must a robot look like, how must it behave, so that people are more likely to accept it?

Martina Mara: One example: robots that look cute and cartoon-like, for example with rounded shapes or friendly eyes on the front, are often met with sympathy. At the same time, studies show that cute machines also make it easier for us to be manipulated, for example to give up personal or even password-relevant data more quickly when such a robot asks us for it. Striving to increase user acceptance through specific designs is therefore often too simplistic a goal; at the very least, it can also raise ethical questions.

ethical questions may arise.

At Contact, visitors encounter a different kind of robot, namely a classic industrial robotic arm that moves in a very specific way and that artists Emanuel Gollob and Magdalena May have given a new interaction tool. Questions raised by this installation are: Do I perceive the robot as a social counterpart despite its machine-like appearance? And if so, what could be the reason for that? Such processes are currently of great interest to us in psychological research.

In AI Forest – The Schwammerl Hunting Game you go on a digital-analogue mushroom hunt. An artificially intelligent app assists with the question of whether the mushrooms found are poisonous or edible. Does our trust in intelligent machines differ when it comes to life or death?

Martina Mara: Basically, the question of trust in someone who gives me a recommendation – be it human, be it machine – is only relevant at all when something is at stake. If a situation does not contain any risk, it is also not trust-agnostic. From this perspective, AI-assisted mushroom hunting is a very useful scenario for our research because many people can empathize well with the situation and understand that something is clearly at stake here. Even if it’s not a matter of life and death, I wouldn’t necessarily want to pick up inedible mushrooms that make me nauseous a few hours after eating the Schwammerlgulasch.

What we would like to discuss with the visitors using the example of the Schwammerl Hunting Game is how much they trust the mushroom identification by an artificial intelligence, which we have fed in advance with thousands of photos of forest mushrooms. Not every person encounters the same AI variant, because from a scientific perspective we want to use the game to systematically investigate the factors on which our trust in AI systems depends and – perhaps especially important – how we can counteract potentially unjustified overconfidence. The more often we are confronted in our everyday lives with AI systems that make suggestions and recommendations for action, the more practically relevant such aspects become.

Martina Mara studied communication sciences in Vienna and received her PhD in psychology from the University of Koblenz-Landau under Prof. Markus Appel on user acceptance of human-like machines. After many years of research work in non-university settings, including at the Ars Electronica Futurelab, she was appointed Professor of Robopsychology at the Linz Institute of Technology (LIT) at JKU in April 2018. Her work focuses on psychological conditions of human-centered technology development and interdisciplinary research strategies. Together with partners from science and industry, she investigates, among other things, effects of simulated emotionality in machine agents or communication designs of autonomous vehicles and collaborative robots. Mara is a member of the Austrian Council for Robotics and Artificial Intelligence (ACRAI). As a newspaper columnist, she regularly comments on current technological events for a wide audience. In 2018, she was awarded the BAWAG Women’s Prize as well as the Futurezone Award in the category “Women in Tech”.