How closely are commercial AI systems entangled with military technology? Awarded the STARTS Prize 2025 Grand Prize –Artistic Exploration, this project reveals hidden connections.

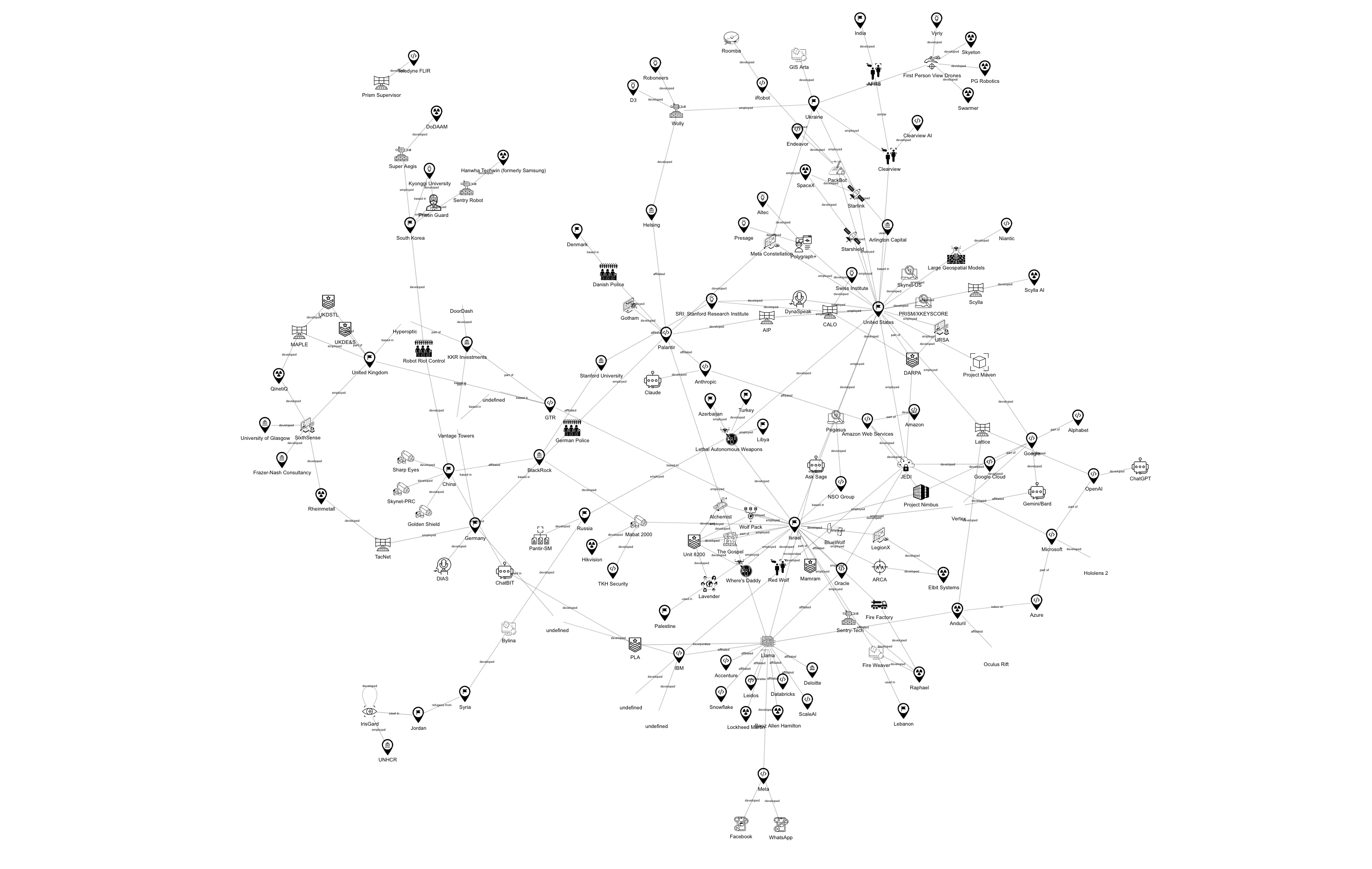

How do the everyday technologies we invite into our lives—smartphones, robot vacuums, voice assistants—relate to military decision-making systems capable of deadly force? This urgent question lies at the heart of the AI War Cloud Database by Sarah Ciston, an interactive research and visualization project that maps the shared infrastructures, logics, and corporate actors behind both consumer AI products and AI-enabled warfare.

For this work, Ciston has been awarded the STARTS Prize 2025 in the category “Grand Prize – Artistic Exploration”, which honors artistic projects that critically engage with science and technology and contribute to social or ecological transformation. Presented by the European Commission, the STARTS Prize highlights innovative works at the intersection of Science, Technology and the Arts.

In this interview, we speak with the project’s creator about the deeply intertwined nature of power, technology, and accountability. Building on the work of advocacy groups like Tech Inquiry and No Tech for Apartheid, the AI War Cloud Database exposes how tools tested on vulnerable populations—from refugees to civilians in conflict zones—are later repackaged and deployed in commercial markets. It invites viewers to follow the threads: the iris scanner used at a border checkpoint becomes biometric login for a banking app; a cleaning robot’s navigation software is refitted for bomb disposal; and generative AI trained on precarious global labor supports both casual search queries and battlefield decisions.

What emerges is a disturbing picture of what Sarah Ciston calls a “techno-imperial boomerang”—a loop in which experimentation on the margins returns to affect us all. In the conversation that follows, we explore not only how these connections function, but what it might take to resist or reimagine them: from individual choices around tech use to collective efforts in policy, programming, and art.

Your project emphasizes the themes of connection and power. Could you elaborate on how these interact within the context of AI and war?

Sarah Ciston: Wielding and consolidating power often comes through the ability to leverage connections, often at scales beyond our daily lives—from the macro scale of nations, corporations, borders, and trade routes; to the microscale of computation. AI systems leverage the speed and scale of computation to find patterns in large amounts of data more quickly than we could otherwise process. But that means in order to rely on AI systems, we have to buy into their logics of classification and compression of information.

“Operating at scales we cannot see or control, we are asked to trust. Projects like AI War Cloud Database try to make AI systems a bit more visible and comprehensible, in order to understand how they are wielded in service of those in power.”

What role do everyday AI systems—like the ones embedded in our phones and smart homes—play in the broader landscape of AI militarization and control?

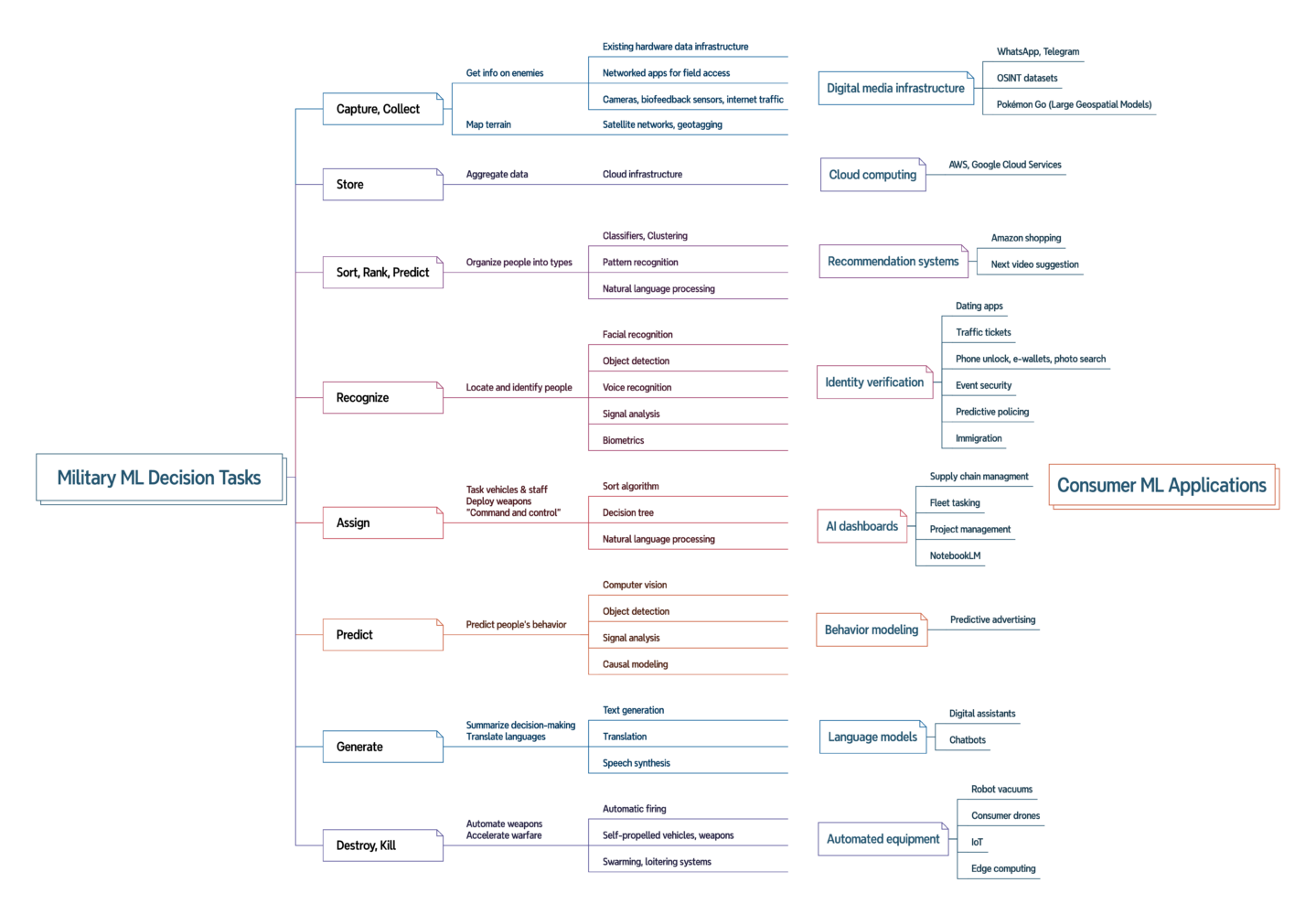

Sarah Ciston: Not only are some of the same companies involved, as we are hearing about more and more—but also the same types of AI tasks are being used in both domains. The recommendation systems we use to pick streaming movies and films use the same kinds of AI that work overseas to select targets for killing.

“The generative AI that we use for writing, research, image making, and an increasing number of tasks (with often unreliable results!) are incorporated into “command and control” systems that advise on real-time high-stakes battlefield decisions. Almost every commercial AI task has a military-equivalent version being researched or already deployed.”

These systems are being adapted in both directions, despite the different contexts. Sometimes the same companies pivot from one industry to the other. For example, the makers of Roomba’s house-cleaning robots that map users’ homes now design bomb sweepers, and the makers of Pokémon Go have speculated how the data from their game can be used to generate AI maps for the military. Along with the big companies you might expect (Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Palantir), a host of small tech startups are jumping into the defense industry, backed by venture capital, experimenting with powerful technologies in unregulated contexts, across borders and on vulnerable populations.

In your view, is it ethically or strategically justifiable to deploy AI in the context of warfare? What considerations must be made?

Sarah Ciston: No.

‘AI’ is a vague term designed to obfuscate its operations and deflect responsibility for its impacts. There is no future improved version of an AI system that would be ‘trustworthy enough’ to consider for high-stakes life-and-death decisions. Even if we were to consider only specific machine learning tasks used for low-stakes activities, there are environmental and other social harms to consider.

If, and this is an ‘if’ with many caveats (I am a realist and I assume people will keep using AI), if AI systems are used in high-risk contexts like warfare, a paradigm shift is needed. For instance, we could consider a shift from human-in-the-loop to AI-in-the-loop, using AI systems as verification and backup to support human effort, rather than to replace it.” AI should not be making impactful decisions or curating choices for those decisions.

Do you also see any constructive or humanitarian applications of AI in conflict zones or military contexts?

Sarah Ciston: You might hope that AI would make warfare safer, more precise, supporting the goal to avoid casualties—but so far AI has been shown to scale up the damage by orders of magnitude. The claims that AI is preventing or reducing harm have been debunked.

“As it is currently applied now, I see very few constructive or humanitarian applications of AI in conflict zones.”

However, if systems could be rethought from different mindsets, made with and by and for the communities most impacted—in any context, not only in conflict zones—I can imagine constructive uses at small scales. Of course, if one is in an active warzone, the priority is not ethical AI design, it is survival. In any context, understanding what is actually needed is not quick or simple, and likely does not fit existing templates or profit models. Better to start with the question, “What is needed?” rather than “What can AI do?”

Accountability is a core theme in your work. What are some of the viable paths toward holding AI systems—or those who deploy them—accountable?

Sarah Ciston: As individuals, I think one of the first and easiest things we can do is not to believe the hype of AI in our own products. I try to make tools to support anyone gaining the basic technical understanding of AI. At least know that it requires vast amounts of data and labor by people, and that it is not ‘smart’ or infallible. I try to opt out whenever feasible and when I dislike how it is being used. And I am striving to select tools made by companies whose values I support instead.

Beyond that, as artists, programmers, makers, we can create our own tools, or collaborate with others to do so. I think art and programming have great capacity, and responsibility, to imagine different futures and experiment tangibly with material solutions. We can also call on policy makers to support more initiatives that build communities for reimagining AI overall.

Do you think AI is reshaping the very nature of conflict? If so, how?

Sarah Ciston: Yes. As with many areas of life, AI systems are expanding, accelerating, and adding complexity to war and conflict. Importantly, AI encourages the entanglement of military power with domestic policing, as the ubiquitous collection of data from our phones and devices feeds into domestic and international surveillance. Many of the examples in AI War Cloud are from companies that market their products both as private security tools and military products, in addition to sometimes featuring other commercial applications. As someone lucky enough not to be living in an active war zone at the moment, in addition to worrying for the world, I am also personally frightened by the way these tools feel so adaptable and so close to home.

Sarah Ciston’s AI War Cloud Database will be presented at the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, September 3–7, 2025. As a Grand Prize winner of the STARTS Prize 2025, the work will be featured in the dedicated STARTS exhibition at POSTCITY—highlighting visionary projects at the intersection of science, technology, and the arts. For the latest updates on this and other program highlights, visit our festival website.

Sarah Ciston

Sarah Ciston builds critical-creative tools to bring intersectional approaches to machine learning. They are the author of “A Critical Field Guide for Working with Machine Learning Datasets” and co-author of Inventing ELIZA: How the First Chatbot Shaped the Future of AI (MIT Press 2026). Currently a Research Fellow at the Center for Advanced Internet Studies, they hold a PhD in Media Arts + Practice from University of Southern California and are the founder of Code Collective: an approachable, interdisciplinary community for co-learning programming.