Requiem for an Exit by Frode Oldereid and Thomas Kvam, winner of a 2025 Golden Nica, explores memory, violence, rhetoric, and the unsettling voice of a machine.

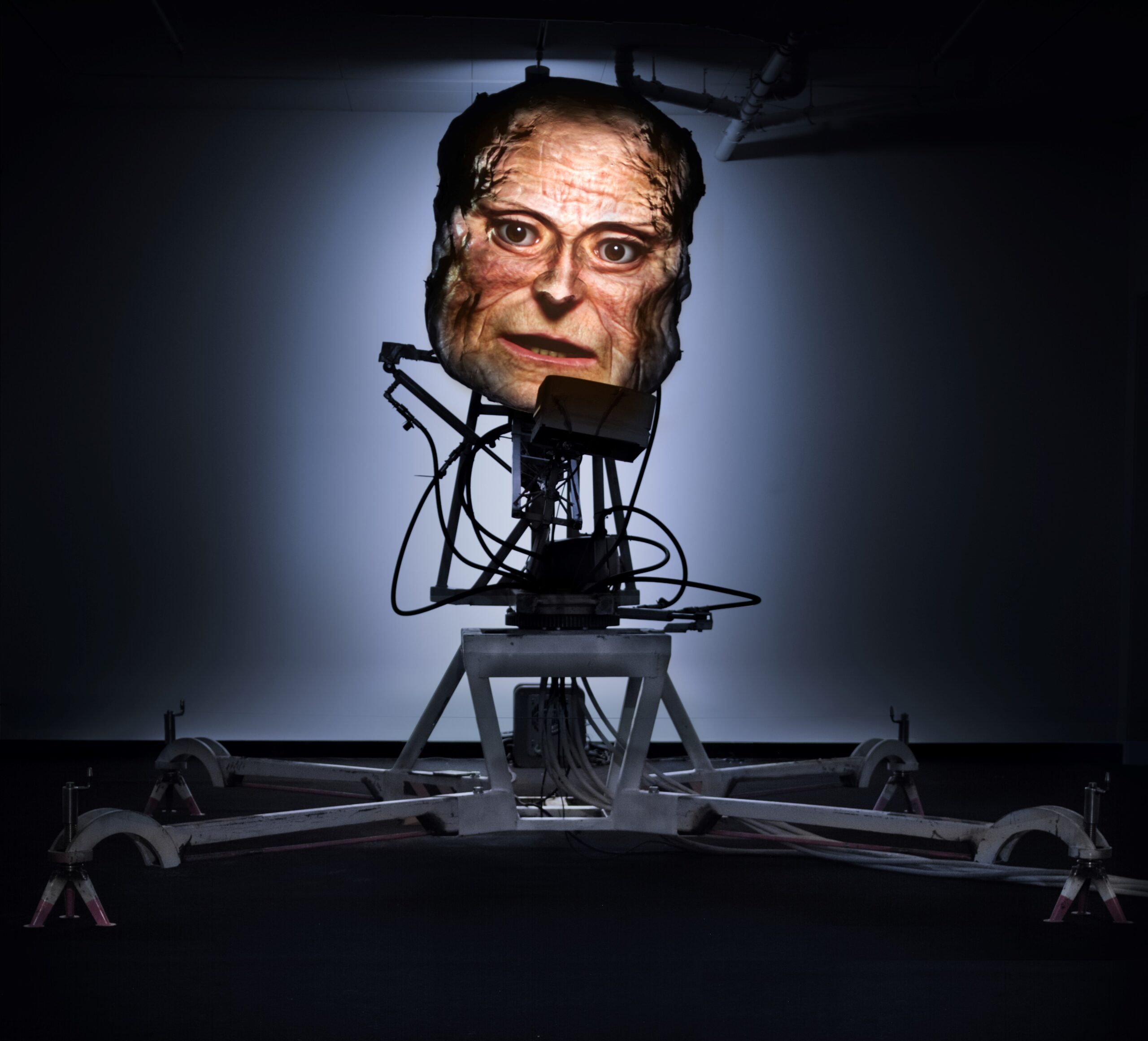

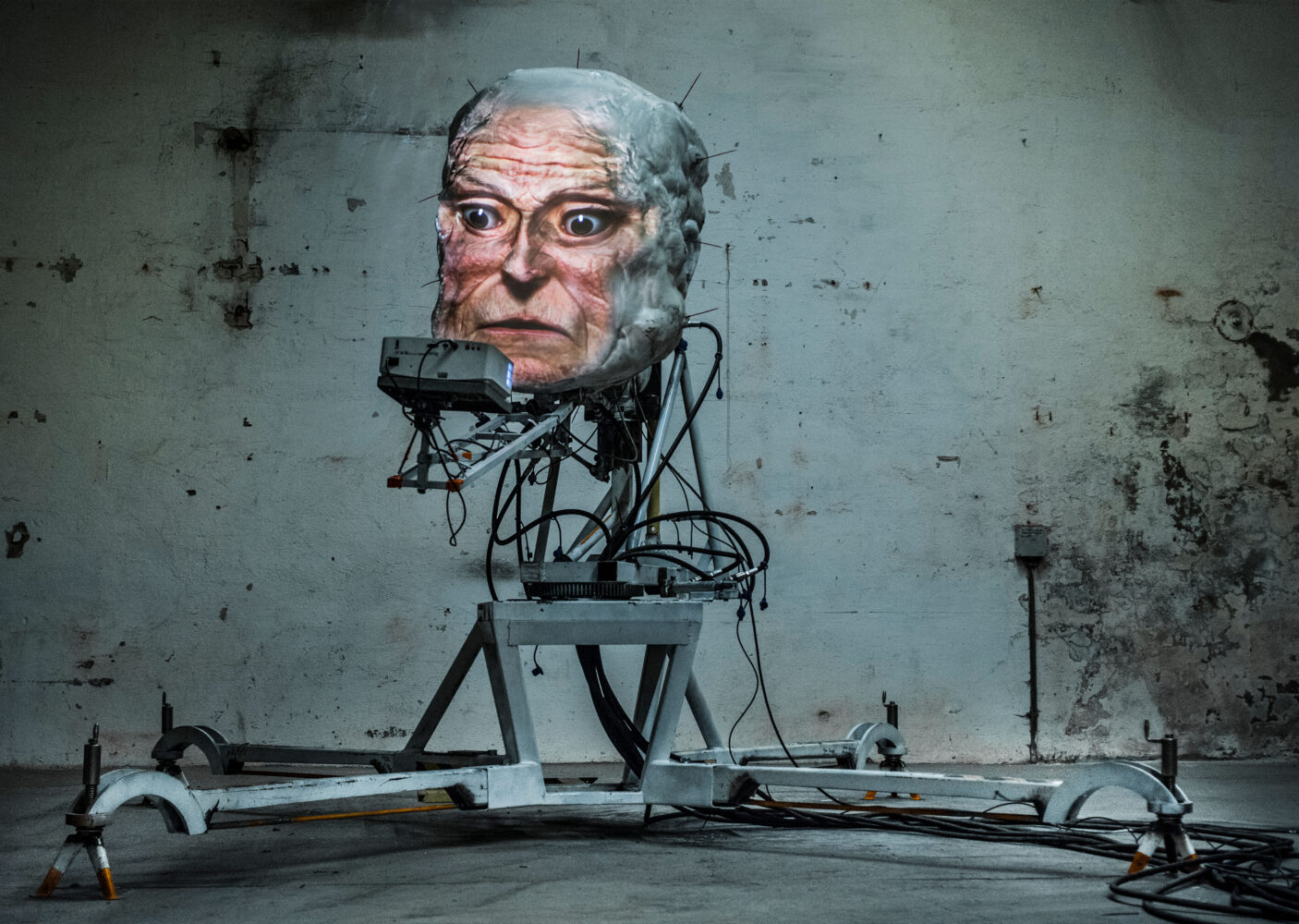

A four-meter robotic figure, rigid and restrained, speaks only through its voice and a slowly moving, hyper-realistic face. Like the demagogues and prophets of history, it speaks with force — but unlike them, its words are its only weapon. In Requiem for an Exit, this exact robot confronts us not with action, but with words: its body fixed, its face lifelike, its voice calm, deliberate, and unrelenting. It delivers no prophecy, no plea. Instead, it performs a reckoning—an archaeology of violence that stretches from prehistoric annihilation to algorithmic detachment.

Created by Norwegian artists Frode Oldereid and Thomas Kvam, this installation marks the culmination of a decades-long exploration of ideology, memory, and machine expression. It is the latest chapter in a series of robotic works begun in the 1990s—machines built from salvaged parts and political fragments, programmed to speak in fractured, haunting tongues.

Here, AI is not the author but the amplifier—used to generate the robot’s voice, enhance its uncanny realism, and expose the paradoxes of simulated empathy. The robot’s monologue, written by the artists themselves, unfolds like liturgy: composed, measured, and saturated with historical weight. It does not seek consensus. It dismantles myths. The myth of technological innocence. The myth of ethical progress. The myth that violence is exceptional, rather than systemic. What emerges is not an answer, but a space of confrontation. Between viewer and machine. Between memory and denial. Between what we inherit and what we choose to reproduce.

In recognition of its haunting power and philosophical depth, Requiem for an Exit was awarded the Golden Nica of the Prix Ars Electronica 2025 in the category New Animation Art. One of the world’s most prestigious awards for media art, the Prix Ars Electronica honors groundbreaking works at the intersection of art, technology, and society. The installation will be presented at the Ars Electronica Festival 2025 in Linz, offering audiences a visceral encounter with the voice of a machine that remembers what we’d rather forget.

To increase our curiosity about the project even more, we spoke to the artists in advance about its history, the role of AI in art, and how doomed humanity really is.

Can you elaborate on the creative process behind Requiem for an Exit? How did the original concept emerge, and what steps were involved in its development? More specifically—how was the monologue shaped? Was it a collaboration between human writers and artificial intelligence, or did it arise through another method?

Thomas Kvam: To understand Requiem for an Exit, you have to go back

to 1995 and the first robot. I built it with salvaged parts: old satellite

motors, relays, and obsolete electronics. The defining element was a cast of my own head, onto which I projected a video of my face—so that the contours matched perfectly.

Frode Oldereid: The video head—stuttering, trapped in a loop—felt almost possessed. When we started working together the following year, it slowly found a language.

Thomas Kvam: That was when we discovered the basic form that would later become Requiem for an Exit. To record the robotic heads, we had to invent tools: we welded a clamp onto a kitchen chair to keep my skull perfectly still. We worked from moods and keywords, but the actual expression emerged in the moment. I sat there, locked in place, the camera fixed, while Oldereid fine-tuned the video projection. Every word became an intense effort, sometimes painful. It was a performance in itself — Oldereid played the soundtrack in our headphones and hit ‘record.’ That experience, of being restrained, of course affected the content.

Frode Oldereid: The following year, when we took the project to the Arvika Festival in Sweden, we transferred that same principle of physical restraint — from Thomas’s clamped-down head to the audience, who were locked inside a shipping container together with the robot. In this confined space, the soundscape was physically overwhelming, with sub-bass frequencies you could feel in your chest.

“The audience had no exit, no safe distance. We wanted to collapse the distinction between observer and participant, turning passive spectators into bodies under control.”

Thomas Kvam: We worked with junk materials and cheap electronics—DIY not for aesthetic reasons, but out of necessity. Still, the ambition was always high: to construct robotic figures with an uncanny presence—distorted, raw, almost like something out of a Francis Bacon painting. Not realistic, but emotionally charged. Not realistic, but affective. The year after, we built a new robot that sampled voices from over a dozen 20th-century ideological leaders—Stalin, Gandhi, Hitler, JFK among them—as if history itself were trying to speak through a broken machine. It became a kind of sonic archaeology.

Frode Oldereid: I especially remember how Ronald Reagan’s measured, almost musical delivery at the Berlin Wall suddenly aligned with a Stalin propaganda speech. It was uncanny. The rhythm and cadence of political speech—regardless of ideology—seemed to follow the same script. We layered these fragments with drum’n’bass and hardcore noise, creating unexpected ideological overlaps. It wasn’t a collage—it was a collision.

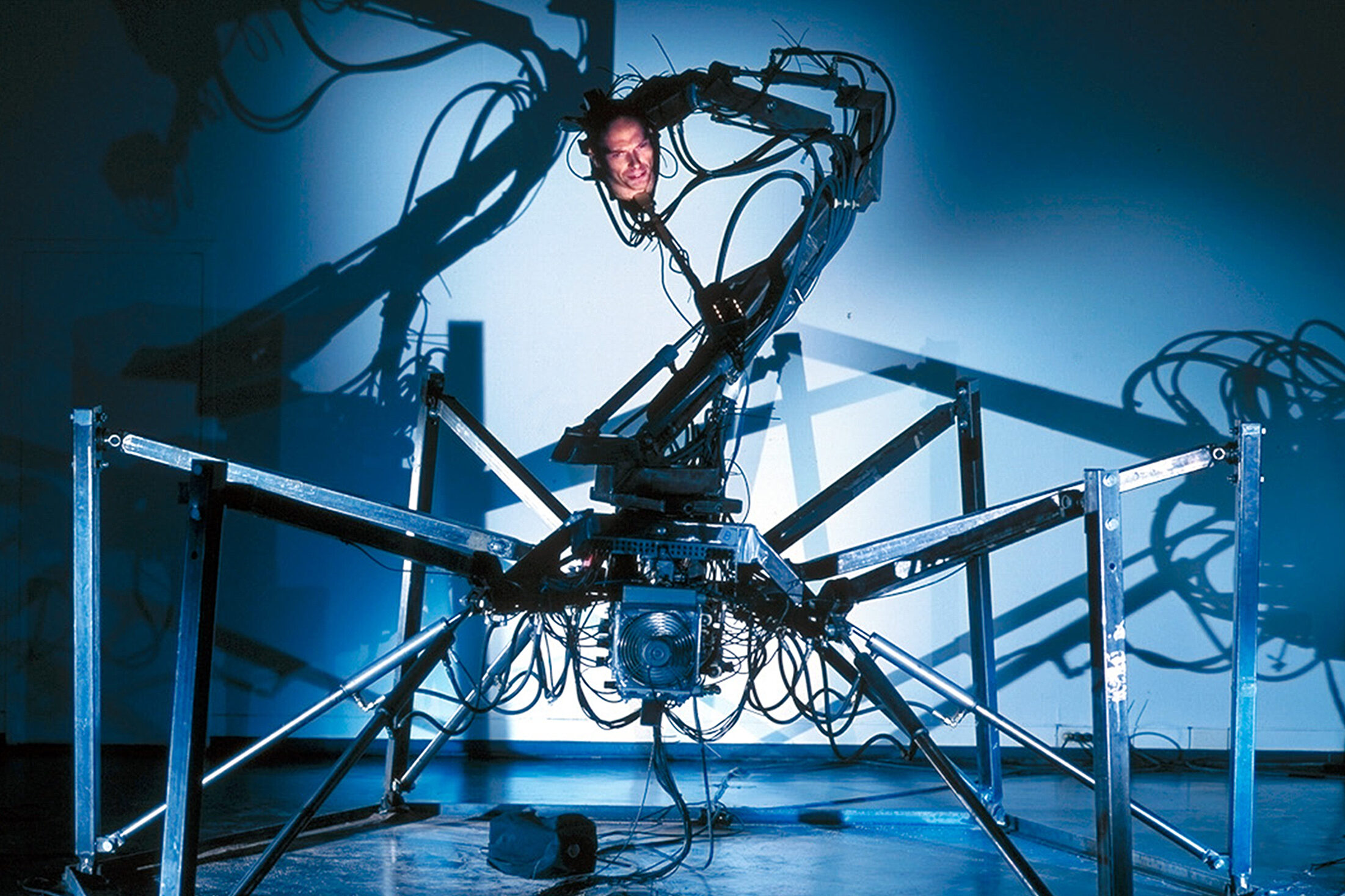

Thomas Kvam: After that, the robots evolved alongside the ideas. Machine 5.1 became a large hydraulic creature, partly inspired by Louise Bourgeois’ monumental Spider sculpture. Its body was built from steel tubes and old car parts scavenged from a London scrapyard, wired to a hacked-together hydraulic unit and rudimentary computer control. The result was an enormous robot—an insectoid being with a central robotic arm that curved like a scorpion’s tail. At the tip, where the sting would be, we mounted the video head.

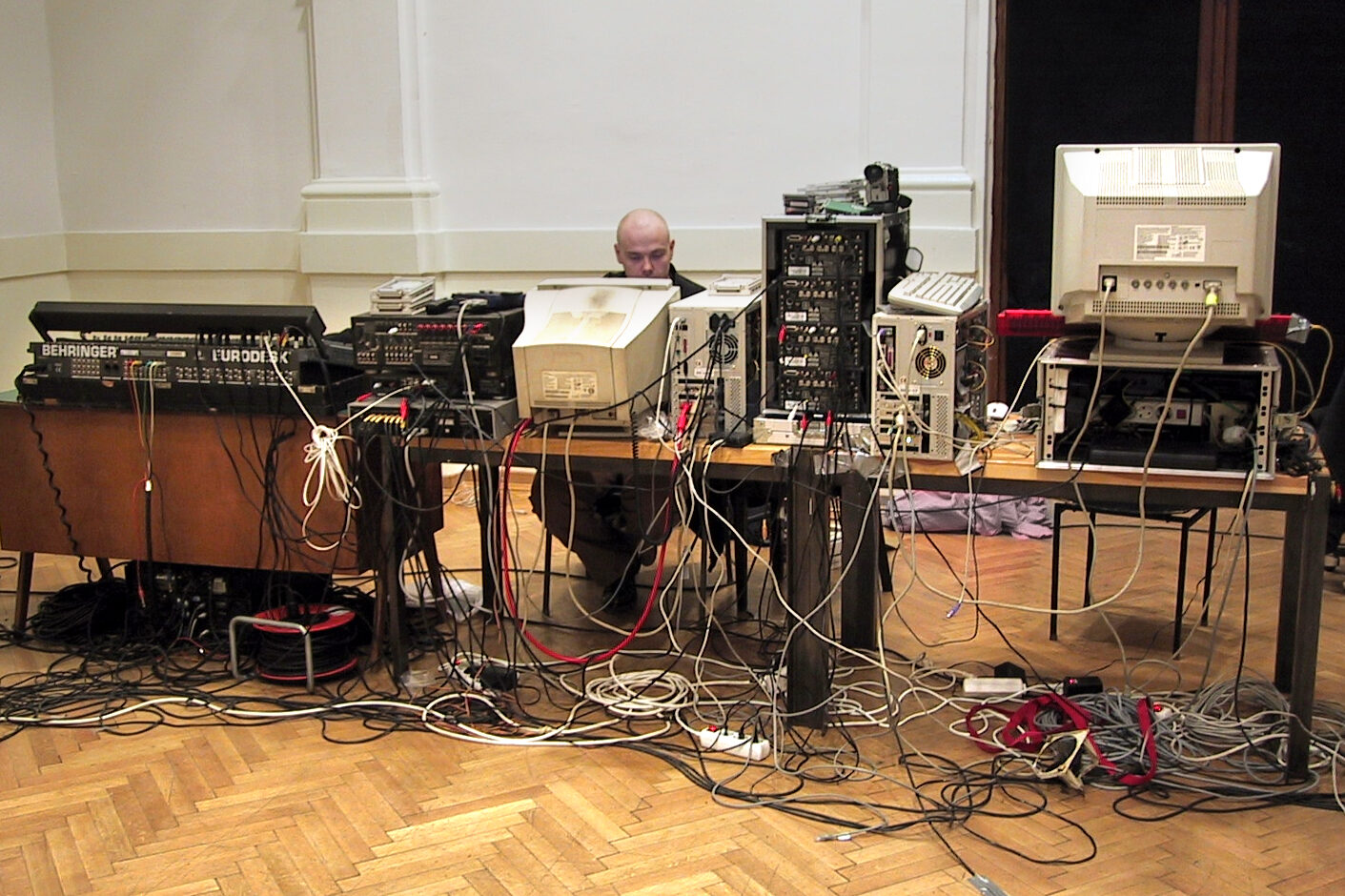

The ambition was to create a kind of posthuman Bob Dylan for the 21st century — a voice that confronts surveillance and capitalism, and calls for revolution. It was about surveillance, capitalism and revolution. When we connected it with Machine 6.0, we suddenly had a stage: a synthesis of technology, sound, ideology, and theatre.

Frode Oldereid: But traveling with nearly a ton of equipment eventually became too much. Physically and mentally exhausting. We had pushed the project to its limit. A break became inevitable.

Thomas Kvam: And that break lasted twenty years. Then, slowly, an idea began to crystallize. Requiem for an Exit was slowly constructed—first as fragments, sketches, and reference materials. We revisited our earlier machines with a critical eye. Out of that process, a new presence took shape: a hybrid being—physically bound, armless, with a projected face simulating presence. A four-meter-high robot with no agency beyond its voice—its rhetoric.

One night in the studio, I recorded the monologue and my facial expressions in a single take. From it, we extracted motion capture data and began sculpting a new head in 3D. The result was a new video face—animated, expressive, and disturbingly lifelike.

In the installation, this robot delivers its monologue in a darkened space, accompanied by a multi-channel sound design that surrounds the viewer. There is no interactivity—only confrontation. The environment is deliberately controlled to heighten emotional impact: the voice, the sound, the scale—everything is calibrated to press in on the body and evoke a tightly contained emotional intensity.

Frode Oldereid: After thirty years, this new project reflects the arc of our collaboration—the robot evolving from a stuttering beginning to a revolutionary agitator, from raw machine intensity to existential reflection. This time, we’ve both stood there with angle grinders and welding torches—physical and philosophical at once.

Thomas Kvam: Maybe it all started in that chair with the clamp on the skull—and now there’s another clamp around our heads. Not a physical restraint, but a cognitive grip: tightened by artificial intelligence and predictive logic.

What role does artificial intelligence play in this installation? Is AI only used for speech synthesis, or does it also contribute to the narrative structure, emotional depth, or philosophical content?

Thomas Kvam: The monologue wasn’t written by AI—it was written by me in dialogue with Oldereid. But it goes deeper. For us, AI is not just a tool—it’s the very process that allowed us to access the emotional and existential expression we’ve been pursuing in this installation.

Frode Oldereid: We had to abandon the human to make the robot more human. It’s a technical and philosophical paradox. We use a complex pipeline—from motion capture to 3D sculpting, and AI-generated speech via ElevenLabs, all the way to rendering and production—to create presence, and empathy. The unease lies in AI’s ambiguity: it generates expressions that feel deeply human, while remaining entirely synthetic.

The robot’s monologue claims that evil is embedded in our genetic material, referring to Neanderthal DNA as a “biological memorial” to humanity’s first genocide. Do you see this as a deterministic view of human nature, or is there room for change and redemption? Can we, as a species, alter this seemingly predetermined fate?

Thomas Kvam: Yes, traces of Neanderthal DNA in modern humans can be read as a biological monument to humanity’s first genocide—but that’s meant as a philosophical provocation, not a scientific thesis. It points to the possibility that history is not only remembered through culture, but inscribed in the body itself. This challenges the divide between nature and ideology, suggesting that even our biology can be caught up in political myth-making.

What interests us is what we inherit, not just genetically, but symbolically and ethically. The question is: What do we carry forward—consciously or not? The monologue doesn’t answer—it destabilizes. It turns the body into an archive and asks us to listen.

Frode Oldereid: Some might interpret this as biopolitical determinism, but our intention is quite the opposite—to dismantle the idea of simple explanations. There is no app against evil. AI is not a quick fix. There is no “ethical upgrade” of humanity, no algorithmic shortcut to goodness.

Thomas Kvam: Exactly—and when we were writing the robot’s monologue, we wanted to reflect that complexity. Not a clear path to redemption, but a descent into moral ambiguity. That’s where I think of Apocalypse Now and Marlon Brando’s monologue as Kurtz—that hypnotic monologue spiraling deeper into darkness. We envisioned something similar: a moral meditation voiced by two minds at once—AI and human fused into a single stream of speech.

Frode Oldereid: To support that descent into ambiguity, the sound design couldn’t just accompany the monologue—it had to embody its atmosphere. We wanted an auditory landscape that intensified the psychological tension, not merely underlining it. The sound had to be dense, enveloping—a presence in itself. It wasn’t there to illustrate, but to act: to draw the audience into the robot’s voice as an emotional space, not a narrative device.

Thomas Kvam: So yes—the monologue may sound deterministic, but it’s really a mirror. Isn’t the Turing test essentially about feelings—about what feels human? And we are easily deceived: a few words in the right order, a sigh in the right place—and we think we’re talking to something alive. We exploit that weakness. It’s an existential question in technological disguise. That’s where art comes in.

Frode Oldereid: Rather than asking who we are, the work asks how many times we will be the same. It confronts repetition itself—those inherited patterns looping through history. But within that cycle lies a question—or perhaps an opening: Can we become something other than what we were? For us, AI is a new language—a way to ask that existential question differently.

Thomas Kvam: What fascinates us is how language and technology—even AI—can manufacture illusions. And maybe that’s the real test—not the Turing test, but the test of recognition:

“Can we hear ourselves in the machine—and choose to speak differently?”

Thomas Kvam and Frode Oldereid’s Requiem for an Exit will be presented at the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, September 3–7, 2025. As a Golden Nica winner of the Prix Ars Electronica 2025, the work will be featured in the most important exhibition of the festival: The Prix Ars Electronica Exhibition. It’s shown for the second time in a row at the Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz and presents outstanding media art projects that were submitted to and awarded the Prix Ars Electronica in 2025. For the latest updates on this and other program highlights, visit our festival website.

Thomas Kvam (NO)

Thomas Kvam (NO) is a conceptual artist and author whose work explores how technological, ideological, and historical systems shape perception, memory, and control. His practice spans painting, robotics, video, animation, and publishing. Projects include Eurobeing (Pompidou Collection), The Chosen Five (2015), and SchizoLeaks (Haugar, 2021). Using WikiLeaks-inspired methods, Kvam has explored the legal and ethical limits of art. He also co-edits Gespenster, a journal for art, literature, and theory.

Frode Oldereid (NO)

Frode Oldereid (NO) is a composer, sound designer, and lecturer with a background in music production, experimental theatre, and robotic art. Active since the 1990s, he has toured internationally with installations and performances. Educated in sound engineering, film, photography, sociology, and urbanism, his work integrates visual media and sonic environments with a focus on socio-political themes.