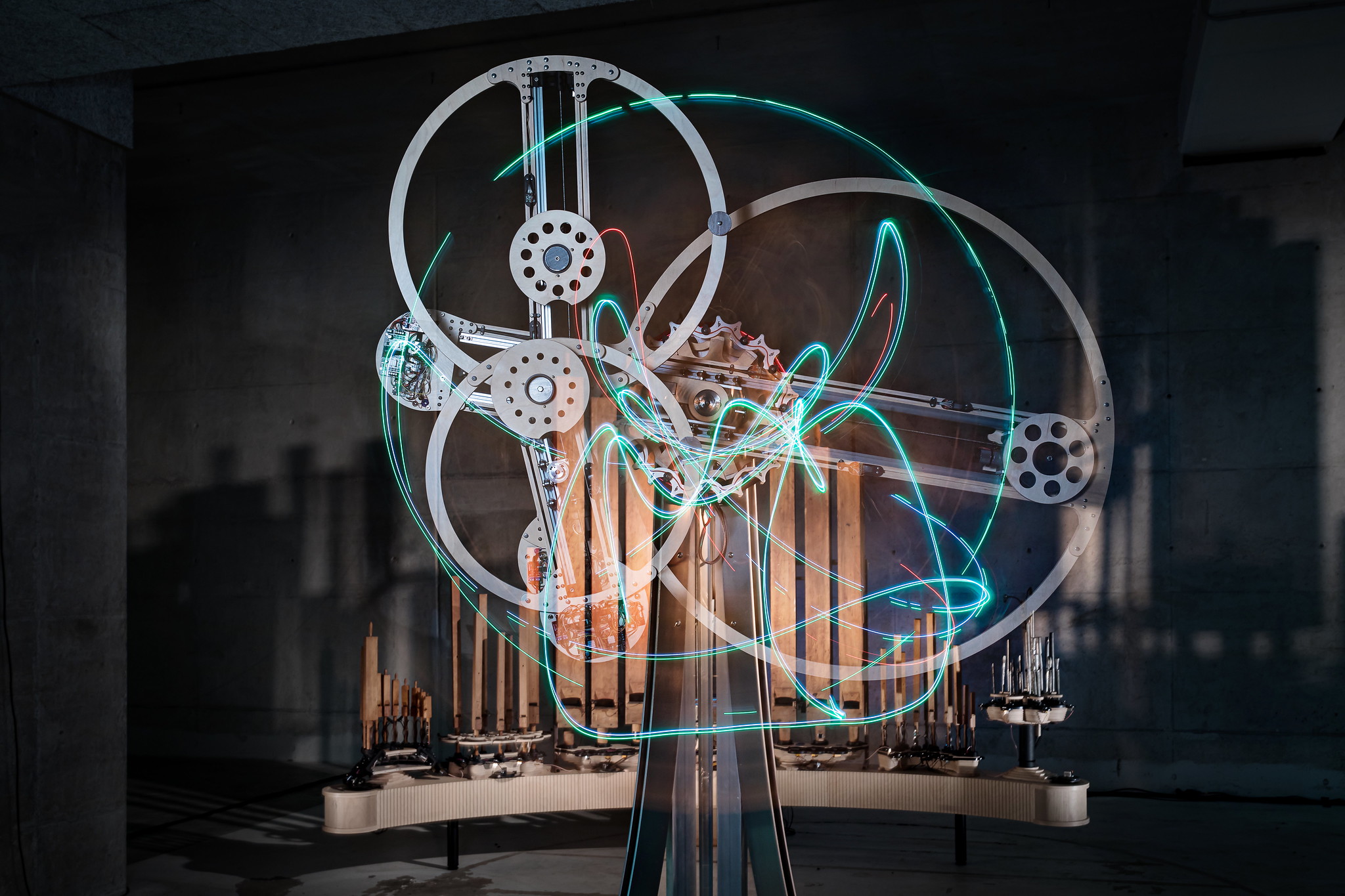

“Organism and Excitable Chaos” combines sound sculpture, instrument, and kinetic experiment. The work explores how organic forms, unstable pipes, and a chaotic pendulum open up new possibilities for the interplay between material, sound, and audience.

What happens when chaos is not tamed but placed at the center of a work of art as a creative force? In “Organism and Excitable Chaos,” interdisciplinary artist and instrument maker Garnet Willis and composer Navid Navab have developed a sculpture that brings sound, movement, and material into an unpredictable dialogue.

While Navid Navab emphasizes the philosophical and art-historical dimensions of the work, Garnet Willis approaches the project from a practical angle: as a designer, tinkerer, and sound researcher who, through decades of engagement with chaotic systems, has learned not to avoid surprises but to understand them as a driving force behind artistic processes.

In this interview, Garnet Willis talks about the creation of “Organism and Excitable Chaos,” about magical moments when pipes “speak” or pendulums change direction, and about how his work rethinks our relationship to technology, sound, and nature.

Can you describe moments in Organism where the system surprised you or behaved in unexpected, emergent ways?

Garnet Willis: This project has really been a search for surprises, and several moments were key to its development. My perspective is more on the design and problem-solving side, while Navid provides the philosophical and art-science context, tracing connections to Western traditions and showing how the work problematizes them. Together, those very different approaches have been essential for Organism and Excitable Chaos.

The organ (Organism) consists of seven modules arranged in a semicircle, with drawings underway for an eighth. Each module houses families of organ pipes, developed through a long process of iteration and experimentation. Unlike traditional organs, which supply stable air to produce pure tones, our modules destabilize airflow—by starving or overblowing the pipes, or by rapidly modulating air on and off—to see what unexpected sounds emerge. Navid then selects the pipes with the most “personality.”

One of the earliest surprises happened on the very first test module with eight small flutes. Once the mechanical, electronic, and software systems were running, one pipe suddenly began producing speech-like tones, repeating what sounded like “yo babba.” It was uncanny, almost like a baby learning to talk. That moment was so striking that the name “babba” stuck—we now call each module by that name combined with the number of pipes, such as Conic 11 babba or 28 babba. We’ve never reproduced that original sound, but the naming tradition honors that discovery.

By 2023, with Organism functioning, we began exploring Excitable Chaos. We wanted the piece to be a self-generating, sonified dynamical system capable of chaotic behavior—something that would continuously unfold and surprise. After considering various phenomena like flames or turbulence in mist, we settled on the triple pendulum as our site of exploration.

I built the first version in my workshop near Montreal. It allowed adjustments to the pivot points and damping weights, and I carefully gave it enough flexibility to conserve energy without breaking apart. On the very first day, a remarkable surprise occurred: after swinging over the top several times, the pendulum slowed and then completely reversed its axis of rotation—something I hadn’t imagined possible. That was the confirmation we needed.

Navid and I then experimented with it for months, wearing out its ball bearings in the process. From those experiments came the “chaos motor,” which allowed us to sustain and study families of motion over extended time. We discovered that while many configurations produced simple periodic motion, others led to strange and varied manifestations of chaos. These “modes of chaos” eventually led us to design a second, much larger pendulum, dynamically reconfigurable as it swings—able to shift from one chaotic mode to another while carrying energy from its past motion into its future.

For me, these surprises continue a thread in my practice that began in the 1990s, when I first encountered chaotic behavior in my sound sculptures. At first I thought my works were broken, until I realized they were exhibiting the dynamics of complex systems. That realization shaped the “flux” series of works and my ongoing search for ways to design open systems that generate their own forms. Organism and Excitable Chaos is very much part of that trajectory—works that reveal the liveliness hidden in materials, and that continually write their own futures through unpredictable and chaotic behaviors.

From your perspective, how does Organism rethink the relationship between performer and instrument, or between audience and machine?

Garnet Willis: I’ll start with the “audience and machine” aspect. In the installation version of Organism and Excitable Chaos, I think of it less as a machine and more as a kinetic sculpture—though of course it relies on complex machinery. What matters is the immediacy of the experience: audiences can perceive it almost like a natural system, one whose behavior is both visual and sonic. The pendulum functions as a kind of performer, bound up with its own propensity for chaos, continuously shaping the emergent form of the work. It isn’t meant to symbolize nature but simply to be itself in each moment, much like natural processes that transform unpredictably through complex causal chains.

Because its physical and sonic forms are never fully predictable, the work embraces indeterminacy and chaotic entanglement, letting the material intelligence of moving masses find their own modes of balance and expression. This produces a direct, palpable experience of a coherent yet unpredictable process—one that highlights the generative potential of lively materials, challenges our tendency to think of matter as passive, and asks us to trust direct experience as much as language.

Turning to the concert version, Organism in Turbulence, I see it as part of the long tradition of Machine Music. A key figure here is Conlon Nancarrow, who utilized the player piano to create wildly complex polyrhythms at impossible speeds. Yet in his case, every note was predetermined, and complexity never tipped into chaos. In contrast, Robert Morris’s 1968 essay Antiform argued for chance, indeterminacy, and a refusal of prescribed ends—an approach closer to what’s at play here.

In our case, Nancarrow’s punched rolls are replaced by digital controllers that allow sequences to remain plastic and indeterminate rather than fixed in advance. Navid has pushed this performance aspect especially far, and though the concert version is primarily his domain, I can imagine composing my own works for the organ in the future. In the meantime, I’m proud to have helped design and develop the physical instrument that makes this expanded sonic palette possible.

One of the organ’s great strengths is precisely its turbulent unpredictability. Pipes chosen for their instability won’t always behave the same way twice: what worked in rehearsal may fail in performance—or, unexpectedly, yield something wonderful. For Navid, that means entering each concert knowing he’ll need to improvise with whatever the organ gives him. Which, to return to your original question, means that every performance is truly unique.

How did you approach the design and engineering of a system that feels so tactile, perceptive, and alive?

Garnet Willis: I think we all have a primal inclination to engage deeply with the world’s complexity, but modernity has distanced us from it. To paraphrase Paul Shepard: our pre-agrarian ancestors grew into a world of infinite complexity and learned to navigate its sensorial richness with joy and wonder. Modernity, by contrast, rebranded this richness as “chaos” in a negative sense and imposed rigid rational order—monotony and repetition—over what is actually our aesthetic and material birthright.

For me, this is clear when I look outside. Just now a hawk flew through the trees, seizing my attention and pulling me into the woods’ dense richness. That encounter doesn’t need representation; it is its own meaning. But when I walk to a mushroom I’d spotted earlier, I carry a mental “A to B” map that ignores the trees, boulders, and streams in my way. To follow that straight line would mean violence to the forest—chainsaws, bulldozers, bridges. In practice, I weave around obstacles, sometimes stepping on a rock barefoot. That’s reality: direct, embodied experience. Yet our world-building technologies favor the abstract straight line, replacing the “hawkness of the woods” with Cartesian grids. And now, as we push planetary limits, we face the question: Panic? Yes/No.

Organism and Excitable Chaos is also a technology—but one that reverses our utilitarian relationship with machines. Instead of cutting straight lines through complexity, it generates chaos directly in front of us. Its system-aesthetic presents itself as an organic, unmediated whole, at the same scale and pace our bodies inhabit. Tempo was an important design choice: the first test pendulum was too small, producing a frantic, hyperactive motion. By enlarging it, we slowed the tempo into a kinesthetic rhythm that resonates empathically with the audience—much like unconsciously breathing in time with divers in an underwater film.

The organ modules (“babbas”) followed a similar trajectory. Early versions were rectilinear for fabrication efficiency. Once technical problems were solved, we could move beyond straight lines into biomimetic forms, inspired by corals and other underwater life. I’ve long been fascinated by corals—how their morphologies combine geometry and organic form—and used proportions like the Golden Mean to shape arcs and splines that give both organ and pendulum a sense of intuitive kinship. The wooden pipe holder atop the 28 babba, for example, was Navid’s idea, inspired by a lotus root.

In all of this, the goal has been to create a technology that doesn’t impose order but instead embodies complexity, unpredictability, and material liveliness—inviting us back into a direct, embodied relationship with the world.

Garnet Willis

Garnet Willis is an interdisciplinary artist, audio engineer, composer and instrument builder. He combines his disparate skills as, designer, wood and metal-worker, sound engineer and electronics geek to produce multivariate artworks that explore the energetics of interplay between physical form, musical interface, and sound. He has garnered prestigious international awards for his artworks, compositions and recordings, including the ARS Electronica Golden Nica and the Bourges Prize, and has had his work exhibited and performed in the USA, UK, France, Italy, Mexico, the Netherlands, Croatia, Austria and Colombia.