This year’s theme exhibition explores various dimensions and contexts of panic—discover more about the curatorial concept guiding the exhibition, developed by co-curator Manuela Naveau.

PANIC: Complex. Absurd. Ominous.

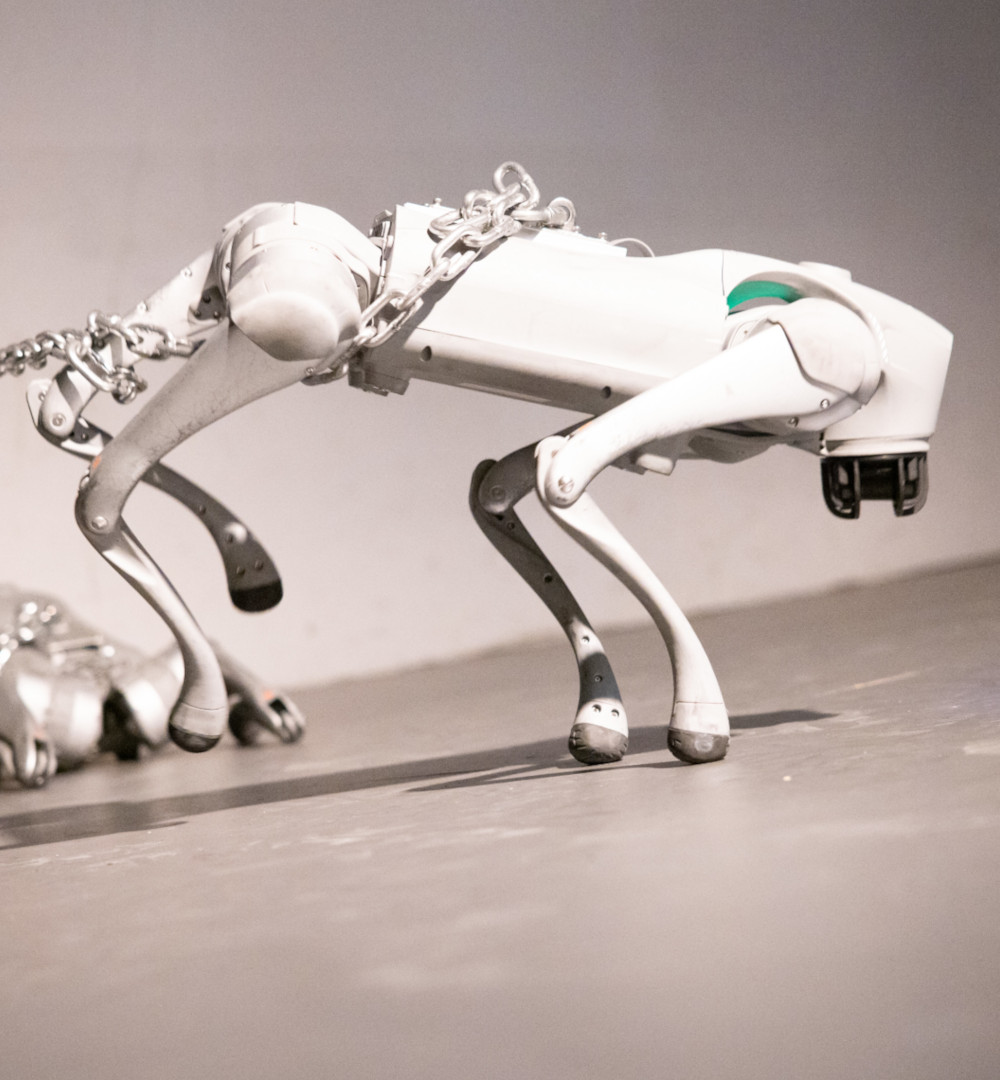

Chapter 1: Moral Limits of Control

What are you willing to accept in order to feel safe and live a comfortable life? How do you evaluate the technological complexity of our reality for yourself? And what happens when control, once reassuring, crosses the boundaries of what you consider ethically sacrosanct? This chapter examines visible and invisible control dynamics and the material consequences they have for individuals and communities. It challenges us to ask what is truly demanded in exchange for stability and how many compromises we are willing to make before things degenerate into the absurd. It is not just a question of the exercise of power, but also about compliance. What happens when we thoughtlessly begin to delegate our own responsibility? The artists in this chapter take a clear stance. They question technological developments that are promoted as promising aids, yet whose side-effects are impossible to overlook. They ask what infrastructures we truly need to control the things that frighten us—and whether this mindset of security genuinely stems from ourselves or is merely the product of an artfully packaged rhetoric of fear, fueled by deeper interests. They challenge us to reflect on how much of our conscience we are willing to trade, and how far we are prepared to let our moral boundaries slip to allow the unthinkable to happen.

Chapter 2: Dystopia as Discourse

Much of our present already feels like dystopia—not as a distant vision, but as an actual condition. This chapter sheds light on this state and draws us onto the discursive level of dystopia—not to accept it, but to perceive it, to recognize its language, and to gain enough distance to begin thinking differently.

We have internalized the language of dystopia so deeply that we barely notice how profoundly it shapes our way of speaking and thinking about the world. In so doing, we forget that not everything is broken, corrupted, or lost. We point fingers—though rarely at ourselves. The foretold collapse always lies elsewhere, never here. Dystopian language thus becomes a means of avoiding confrontation—especially the most painful one, with ourselves. Keeping dystopia on a discursive level has a double effect: it keeps us in a state of constant alertness, feeding fear and insecurity; paradoxically, it also creates a certain detachment, a disconnection from reality. We keep dystopia at a distance, suspended in abstraction, even as it already coexists with us. Art makes use of distance and abstraction, functioning as a powerful “debunker” capable of exposing the true substance of the narratives we willingly allow to emerge within and around us.

Chapter 3: Gets You Nowhere

Panic can easily lead nowhere—that overwhelming feeling of having lost control and being unable to regain it. You’re stuck, paralyzed, but by no means numb. You painfully realize how much everything has fallen apart. It’s so much that the mind falters, seemingly unable to find a way out. Yet inaction can be both ruin and salvation. Sometimes, simply standing still is enough to change perspective – to feel and to root yourself in the here and now. This chapter emphasizes the urgency of renewing our commitment to pause—as an imperfect, yet honest act of resistance. In a time full of noise and oversaturation, losing oneself in stillness can open an unexpected space for awareness. Even when faced with seemingly insoluble problems, we don’t have to completely drown in panic. Instead, we can use it as a lens to recognize what truly matters in the moment. Art invites us to gradually cultivate a conscious presence in the “HERE” and “NOW” – even when fear and the enjoyment of the moment paradoxically lie close together.

Chapter 4: Self Not Found

This chapter addresses the panic that arises when identity is not something that fully belongs to you, but is imposed from the outside. Finding out who you truly are is difficult, isn’t it? It can be a demanding path, full of confusion and uncertainty. You can get lost, unable or unwilling to see yourself clearly. And when the pressure becomes too great, you may be tempted to let something else take control. But at what cost? Society pushes us into roles we must accept. We cannot afford to be excluded, so we conform to standardized forms—even if they feel wrong. We wear social masks that bind us, merging with others, dissolving in the flow of social constructions. In the end, we no longer recognize ourselves; the boundary between true face and mask becomes paper-thin. We borrow an identity because we cannot find our own or believe that what we are is not good enough. The scenario worsens when technology alone is granted the power over your identity, trained according to the opinions and ideas of people unknown to you who decide on your behalf. What, then, becomes of your say in your (digital) identity? The works in this chapter question identity constructions and stereotypes, asking how people in an increasingly technologized world can maintain their authenticity and self-determination.

Chapter 5: Marketing to Death

Have you ever imagined a world without marketing or advertising? The logic of the market follows a clear principle: to create needs, to promote, to sell land to occupy public space in such a way that not only the supposedly best product or service, but above all the loudest voice, gains the most attention. Allegedly, this was already the case in ancient Greece. The ancient Greek word Agora (ἀγορά) referred to the market square, a public space where people appeared as different yet equal actors. A place of spectacle, commercial exchange, and dialogued dimensions of public life that coexisted and influenced one another. Here, the plurality and diversity of life unfolded: things were promoted, consumed, negotiated, and debated. From this historical perspective, we pose a hypothesis: Does and if so, how—the “glorious” rise of marketing relate to the invention of the computer? To what extent has advertising become automated, permeating every area of our lives from birth to death, keeping us captive in narratives of greatness, growth, and a supposedly glorious future? Are these truly narratives that match our needs today? And finally: What would happen if we seriously asked ourselves what a world without marketing might look like? Is there still any corner of our lives that it hasn’t penetrated, and shouldn’t we therefore start rethinking marketing in relation to the public sphere in general?

Chapter 6: State of the ART(ist)

State of the ART(ist) is the award that Ars Electronica grants to artists whose creative and personal freedom is under threat. This chapter opens a space to listen to those who face war, instability, danger, and a multitude of life-threatening situations on a daily basis.

We create space: a space for reflection beyond mere speculation, where injustice and violence are tangible realities. A space that demonstrates that artistic production cannot be erased, even under the most difficult living and working conditions. A space that exists for unyielding voices—voices that, loud and clear, bridge distances we do not yet know how to measure. A space that makes palpable the urgency in which those live who stand on the threshold between survival and annihilation. Beyond any glorification of pain or empty spectacle, art here is a means against erasure and oppression—one of the few possible ways to keep alive what others seek to destroy. Perhaps a flash of light in turn for others who have yet to find such a space for themselves.

Chapter 7: Living Conditions

This chapter focuses on the material foundation of our living conditions—the elemental needs that shape the environments in which we exist. Water, a protective atmosphere, and a delicate ecological balance make our life possible. Yet this balance is increasingly faltering, not least due to the numerous interventions by humans. This instability represents a particular threat to ourselves. Driven by this, we turn our gaze to distant spheres, to other worlds, hoping to find or create there what here has been irretrievably damaged. We dream of balance without being aware that the process of constant adjustment might itself be a natural cycle we should follow. Instead, we devise theories on how life could be constructed, replicated, and exported in synthetic environments—in the hope of extending what we have so far failed to preserve. We are well aware of the fragility of our world, yet at the same time we nourish a paradox: we search for something that already exists, while refusing to cultivate the necessary adaptability within ourselves. We project our hopes into abstract visions of the future, but what we truly need to live cannot be outsourced or postponed. It is here, now, and has always been present. What if true learning consists in staying—lingering and acting? Perhaps that is the most powerful and radical act still open to us.

Chapter 8: World at Stake

This chapter closes the circle: all previously addressed topics converge here, pointing to a single, decentralized, and distributed crisis, and we begin to understand that everything we know and rely on is being questioned. “Nothing less than the world is at stake” (Total Refusal). Truly grasping what this means, however, does not mean getting stuck in a recursive logic where everything repeats endlessly, trapped with no way out and no possibility of moving toward something new. Like in a game, individual and collective reflection and action are necessary to make the next move or reach the next goal. Like in a game, laughter and tears are allowed, for only through emotional connection can we act authentically. Like in a game, there are those who lose and those who win. But this is only a moment, because in the next instant the situation can change. Ultimately, as in every game, it is above all about the process of playing, even when the world is at stake.

Rules of the game—additions welcome…

— Treat ourselves and others with greater care and gentleness,

— Ask the hardest questions,

— Find the courage to seek answers even among the most painful truths,

— Face the moment of truth,Practice caring,

— Reject simplifications,

— Take a deep breath and endure uncertainty,

— Find words to express what is necessary,

— Hold on to complexity without withdrawing,

— Embrace ourselves in resilience,

— Dare to unlearn and learn again and again,

— How to care for what truly matters,