Photo: Florian Voggeneder

Visionary pioneers laid the cornerstone of contemporary media art and thereby made a decisive impact on the work of many media artists throughout the world. To give these trailblazers and their accomplishments the respectful recognition they deserve, the Prix Ars Electronica launched a Visionary Pioneers of Media Art category in 2014. The debut honoree, Roy Ascott, was selected by a jury of his peers—all those who have themselves been the recipient of a Golden Nica since the Prix Ars Electronica‘s inception in 1987. We met with Roy Ascott shortly before the prize was bestowed upon him at the Ars Electronica Gala in Linz’s Brucknerhaus.

Roy Ascott, born October 26, 1934 in Bath, is an artist, theoretician and visionary thinker who’s been active since the 1960s, and whose numerous publications and works have exerted a major influence on the global digital art community. He has exhibited his works at such venues as the Venice Biennale, the Shanghai Biennale, the Milan Triennale, the Ars Electronica Festival, the Plymouth Arts Centre and the Incheon International Arts Festival in South Korea. In the early 1980s and thus even before the birth of the internet, Ascott presented one of the world’s first online art projects on the ARPANET for universities. In 1989, Roy Ascott appeared at the Ars Electronica Festival, where he presented an installation entitled “Aspects of Gaia.” In 1990, he served as a Prix juror in the Interactive Art category which premiered that year.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IW4p9fct_Zs&w=610]

Mr. Ascott, let’s say you have the opportunity to write an encyclopedia entry about you as a Visionary Pioneer of Media Art, what would you write?

Roy Ascott: I think I have managed to be lucky and able to match the future desire. I think all technology comes out of desire. And all art comes out of desire. To be able to have a vision, to be able to have certain specific ideas – what could be my case – and then find support in some people, institutions and situations, to make things possible, is indeed lucky. It’s hard to really describe exactly but I do think it means having a pretty clear sense of what would be great to have in the future. And having hands, tools, people and situations that you can bring together to realize that. There isn’t anything mystical about it, I didn’t stand on top of a mountain but I had a pretty clear idea of how I thought things could become. I used to write about on that quite a lot and I’ve been very lucky that things actually turned out that way. Beyond that I can’t really comment *laughs*

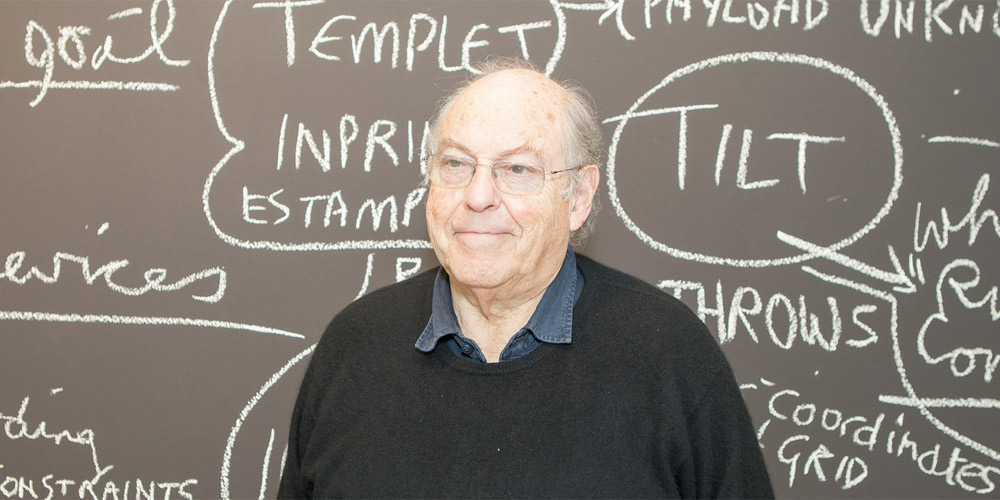

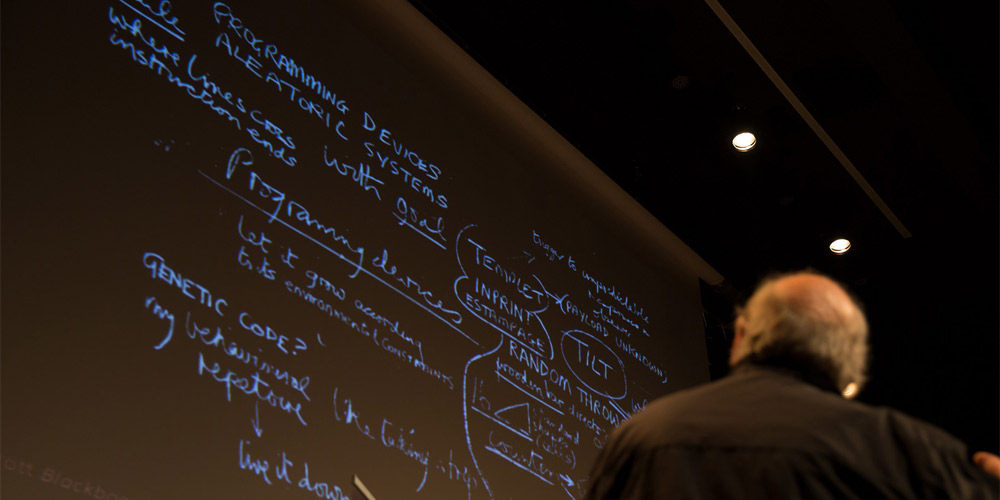

Roy Ascott during the Festival Ars Electronica 2014, Photo: Tom Mesic

Back to Linz – you did the concept design of the “Interactive elevator” or “Televator”, a permanent installation at the Ars Electronica Center since its beginning in 1996…

Roy Ascott: The first design was actually the closed what I had in mind. Inside the elevator you were standing on a screen that enabled you to surge upwards from the ground up of the building and go up into space. And that was beautifully realized, particularly when the rocket shot up. But I know that very inventive designs followed like one going up through a human body.

You’ve regularly visited the Festival Ars Electronica in the past years, and you were involved in the Prix Ars Electronica in early years. What was your first connection to Ars Electronica?

Roy Ascott: I can’t remember the chronology exactly but I had a professorship of information theory at the Angewandte, the University for Applied Arts Vienna, for five or six years. I was involved with a Canadian artists who lived in Austria for many years, Robert Adrian X, and I did a lot of projects with him and his wife Heidi Grundmann. She had a program called Kunstradio. I spent a lot of time with them and they actually introduced me to the Angewandte.

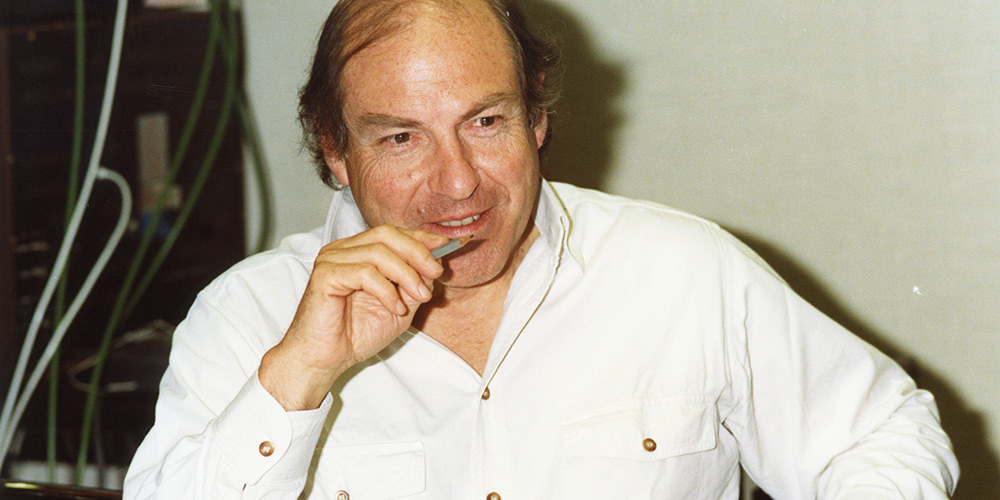

Roy Ascott, part of the Prix jury 1990, Photo: ORF

It’s a long time ago but I’ve been involved with Linz, Vienna and Graz. In the early days when I came here, both simultaneously and Peter Weibel asked me to write an article in 1989. And we simultaneously and independently said that there really should be a category of “Interactive Art”. It’s really a form of art that we can talk about, it has a body of work. And the next year in 1990 the Prix Ars Electronica introduced a Golden Nica for “Interactive Art” and I was part of the first jury of this category. For me that was the beginning of the maturing of our field. At this time there were large special effects, sounds or images and interactivity entered and enabled the viewer to participate. I think we really moved into a stage that gives the legitimacy for this art form.

Concerning my first contact with Ars Electronica I don’t know the actual chronology at all, it has a bit lost in time. In 1982 Robert Adrian X established a private network for his performance called „The World in 24 Hours“ and he connected 24 artists around the world with the city of Linz. That was one of the early telematic pieces here that I was engaged.

Roy Ascott during the Prix ceremony 2014, Photo: Florian Voggeneder

Today there are many young media artists who create their own works. Could you give them, as a Visionary Pioneer of Media Art, an advice?

Roy Ascott: I think we should lead from the heart. We have to work from the inside out rather to respond emotionally to the situation. A great deal of art – whenever it is media art or any other – is a response to the tools, a response to the technology, the response to the conventions of the galleries of the time. I think there is a big danger in our field because we all love iPhones, iPads and the lasted things, and the more sophisticated they are technologically the more wonderful are its technological possibilities. But I believe we should lead from the heart, and from what it is important, and then reach out to the tools which are much appropriate. If they aren’t the tools to do what you want, than yes, you have to see what it is possible. I think that’s the shadow that hangs over our field of interactive art: All the kind of technology for its own sake. So, this is why I think we need a much more rounded holistic position. *laughs*