The 2017 Ars Electronica Animation Festival has an extensive program lined up—just the stuff for animation fan and those who are about to become devoted enthusiasts! A screening of the best submissions for prize consideration to the Prix Ars Electronica’s Computer Animation/Film/VFX category offers a cross-section of the latest trends in this genre. The 15 top films will also be featured in the Electronic Theater at OK Night on Saturday, September 9th. The Computer Animation/Film/VFX prize recipients will have their say in the Prix Forum. Festivalgoers can experience animation artists live at the Expanded Animation symposium series—“Hybrid Technologies in Animation – Daydreams and Nightmares” is the theme; the four panels will go into the ongoing development and expansion of animation technology. Other attractions include VR installations and two In-Persona screenings with the filmmakers in attendance.

We talked to the organizational team—Alexander Wilhelm, Jürgen Hagler and Christine Schöpf—about this year’s Prix submissions, trends in animation and the festival program.

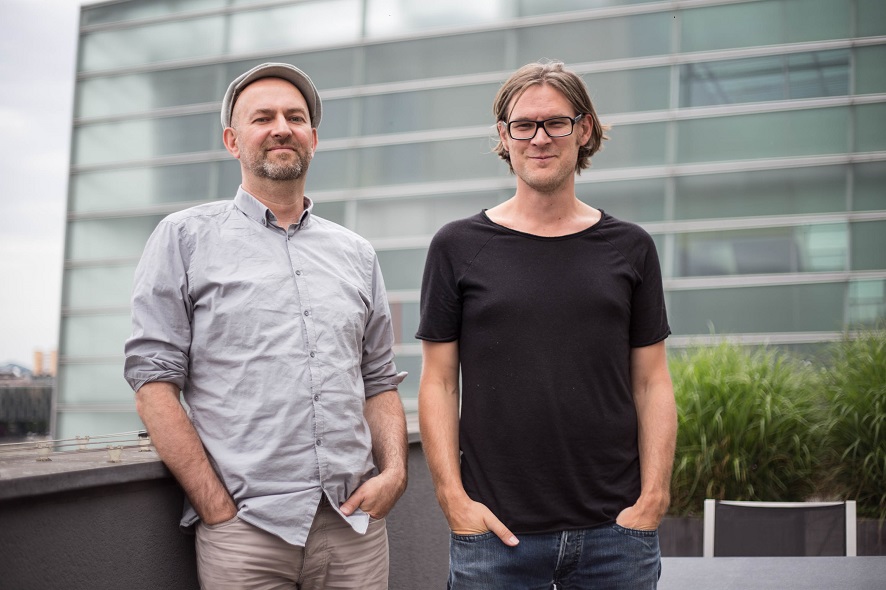

Alexander Wilhelm and Jürgen Hagler. Credit: Vanessa Graf

This year’s symposium topic is “Hybrid Technologies in Animation.” What’s this all about?

Alexander Wilhelm: The symposium is, so to speak, a concentrated presentation of everything that Expanded Animation stands for. It’s an acknowledgment that animation has completely cast off any and all media restrictions or limitations. We’ve been observing this for quite some time now. Today, there are people who, in a very significant way, are synthesizing technologies in a form that had simply been impossible before because neither the financing nor the software was available. We suddenly have hybrids. A prime example is Hamill Industries, which took the technique of light painting, which has been around for quite a while, and took it to a completely new level. They use robot arms and the like to create an intentionally designed, analog-animated sequence, and film it in a stop-motion process. Here, everything comes together: stop-motion, light painting—that is, camera motion control—robots that move the lights, lots of stuff that simply would have been impossible to finance years ago, and this playful approach just would not have been able to happen. Now, we’ve reached a point at which you can mix and recombine any classic form of animation. This is precisely what we want to showcase.

In addition to robots, what are some of the other technologies now being deployed in animation?

Jürgen Hagler: There’s a long list of technologies that are used in animation in ways other than what their manufacturers originally intended! When you look back a bit, you see that this is actually nothing new—the very first artistic animation, as it were, was a misuse of military technology. This occurs pretty often in the history of the development of animation—a technology like the drone, which was developed for a completely different deployment, suddenly attracts the interest of animators. “The Box,” a film that came out a few years ago, is a terrific example. The idea was to use a computer to produce an animated film that’s then used to control a gigantic robot that, in turn, creates another animated film. Rapid prototyping is another trend in which something that’s been around for a while was subsequently used in conjunction with stop-motion and proved its merits as a creative tool. In addition to clay and puppet animation, people are now using the computer to generate animated films in which the animation is again done physically via stop-motion. Raphael Vangelis, who’s coming to the festival, created a lovely example.

“Analogue Loaders.”

Alexander Wilhelm: Exactly. This also applies to things like “Blooms” by John Edmark. He has recourse to what is actually ancient technology, the zootrope, this old-fashioned drum with the viewing slits in the wall. He transforms it into three-dimensional, spherical fractals that then show that everything is a movement. It looks like a sculpture but it’s actually a cyclical loop that was milled plastically via rapid prototyping. This is truly condensed animation.

Jürgen Hagler: This is also an example of an animated film that was created digitally and transferred back into an analog form.

Alexander Wilhelm: It also demonstrates the hybrid nature of these times. There’s this traditional form of zootrope, the original carnival attraction showing moving pictures, and now we’ve reached the point at which this is precisely what people are bringing back and reestablishing—but with all the technology that’s available today. And at a much higher level of complexity, since it’s an extremely elaborate mathematical process to even generate these forms. Manually, it would be almost impossible. All of a sudden, people are creating this carnival attraction, but what it actually consists of is fractal geometries, pure mathematics, very precisely worked out. So it’s what you might call a chronological hybrid, a synthesis of the time.

Jürgen Hagler: “Ugly” by Nikita Diakur is another example. This animated film was nominated for a STARTS Prize and received an Honorary Mention from the Prix Ars Electronica. The film deals with precisely what we’re talking about here: animation, simulation, real time. It’s also a textbook example of hybrid technology since it’s a technologization of game engines and/or computer graphics and classic computer animation in real time. At this point, we’ve actually already reached the limit at which a hybrid technology or a sort of outside technology becomes the standard. You can trace this process from the origination of a hybrid technology to its achieving standard status. Drones are another example. Maybe someday it’ll be common to employ a cell phone app to summon your personal drone and stage fireworks, and unmanned aerial vehicles will no longer even be associated with a military background.

Alexander Wilhelm: Another interesting thing about “Ugly” is that it produces a sort of analogy of digital. That is to say: the animator was always forced to some extent to work with a delay and thus not in real time. You always have to compute previews, render them, etc. This isn’t a thing of the past yet, but there’s less and less of it. Now, it’s simply the case that there are so many real-time renderers that make it possible to get immediate, one-to-one feedback. Nikita Diakur selected a style that already makes that possible now. His idea is, in principle, to create digital actors/actresses who are subject to simple processes. He, as the director, simply gives a direction for them to go in. This is based on a simulation. It’s a sort of a spontaneous working process that is, nevertheless, based on computer animation. This brings spontaneity back into a field that originally had none.

This creation of an analogy of digital, why is it happening now? What’s the attraction?

Alexander Wilhelm: Because it’s possible now. Because it has an aesthetic that’s accessible to people’s innate instincts. We understand the world into which we’re born intuitively, so to speak, with its physicality, with gravity, with randomness. We can interpret that; that’s our game. Seeing such things is more pleasant for us than completely synthesized things. As an animator, you know that you have to put a lot of analog behavior into things for people to even be able to look at them. It’s hardly bearable when something is too linear, too tidy, too smooth—it really injures your sensibilities. I believe that these random elements bring with them a quality of density of detail, of acceleration, of deceleration, of physicality like gravity …

Jürgen Hagler: It simply has this charm. The very fact that you imagine that you’re animating on the computer and the individual images are printed out as sculptures and these are then shot in stop-motion—I mean, you really have to ask yourself “Why am I even doing this?” It’s simply a matter of the charm of the analog, that this aesthetic—which, of course, can be simulated on the computer in many different ways—has totally different qualities that work done on the computer can’t even come close to.

Alexander Wilhelm: And this will go a lot further in the future. Now, we’re seeing the pioneers in this field, and we’ll soon be seeing where this leads. This expedition to discover how we can impart to our computers the fine granularity that we see in reality, this is somehow the hunt that people have always gone out on. We’ve now arrived at a point at which you can really see results and these aren’t just thought experiments.

Speaking of daydreams: Expanded Animation’s subtitle this year is “Daydreams and Nightmares.” What’s meant by this?

Alexander Wilhelm: This means that artists are essentially those commissioned to generate daydreams. We imagine images and compositions, we dream up things that later come into the world. Those are the daydreams. Many of these hybrid artists who use these techniques don’t do so as an end in itself but rather because, in their search for ways in which to turn their daydreams into reality, they realize that such techniques can achieve precisely the style or the quality that they’re looking for. In this way, we create a new synthesis, a new work. In going about this, however, you have to do a lot of experimentation. And the results of this are sleepless nights, the nightmares of implementation, because it truly entails trailblazing. The work is incredibly demanding and often brings disappointment; only those with powerful visions can overcome these nightmares until what emerges in the end is a daydream that everyone can partake of.

Jürgen Hagler: This pioneering work is always associated with experimentation, failure, and promising results. Frequently, the outcome is a new path that can then be taken by many others.

Alexander Wilhelm: I hope that we hear a lot about failing at the symposium. This show that we’re all familiar with—the one in which we all succeed and everything works—this covers up about 99% of the development process, which essentially consists of failing.

In their talk “How Not to Win an Oscar,” Job, Joris & Marieke discuss their animated film “A Single Life,” which was nominated for the Oscar in 2015 but ultimately lost to Disney. So this has a little bit to do with failure too…

Jürgen Hagler: Job, Joris and Mareike are, of course, not a textbook example of failure in this experiment. They, together with Max Hattler, are among the participants in our Artist Position panel. Max Hattler, for example, is an artist who I believe has not yet reached the end of his experimentation process. He works out digital abstractions in the tradition of the early abstract, analog filmmakers like Richter and Fischinger. He’s created a work that experiments with stereoscopy, in which he explores this struggle between the left and right images.

Alexander Wilhelm: I often imagine that, actually, the artist’s task is always to be perhaps uncustomary and cumbersome now, but in truth to be creating the form of expression of everyone in the future. Consider music, for example—think about what used to be experiments and is simply normal today. This expansion of the possibilities of human expression, that’s the artist’s task. These pioneering works we want to present now, or the thoughts behind them—at some point in the future, they’ll be the production methods used by everyone. This is the astounding thing about it!

Which pioneers can we look forward to?

Jürgen Hagler: Lev Manovich is a real pioneer with respect to computer animation and media theory. Plus, his works deal with the festival theme, artificial intelligence. You can see this in Nikita Diakur’s work too—that is, when the computer assumes control with the simulation and then the director, as if on a film set, captures images with the camera of things that more or less happen by chance, but the characters are actually controlled by computer. So this brings us to approximately the point at which artificial intelligence plays a major role in computer animation. Hamill Industries, whose “Floating Points” received a STARTS Prize nomination last year, are also pioneers, and so is Raphael Vangelis with his “Analogue Loaders.”

Gaming is also a major topic. Nikita Diakur experiments with real-time game engines; Stefan Schwingeler, a media theoretician who deals with the artistic hybrid material of digital gaming, will also give a talk, as will Stefan Srb who, as an indie developer, blazes new trails when it comes to storytelling and game mechanics. This is very widespread at this interface with animation—computer games become artistic material, material for moving pictures, for storytelling and for experiments in the gaming field.

Pioneering work is being done by onformative studio. They submitted two works this year: one is a projection mapping of a sphere, an exquisite installation; the second is a combination of VR and visualization. In their work too, there’s always a strong mix of technology.

The heart and soul of the Animation Festivals is the screening. How do you go about choosing the ones to be screened at the festival from among all the submissions to the Prix Ars Electronica?

Christine Schöpf: We always select from the material that’s submitted to the Prix jury. There’s a shortlisting process to pre-select works that will be presented at the jury sessions. We work with these submissions too. We view all the candidates once again and then we attempt to order them thematically. We ask ourselves: How do these works fit together? And the result of this is a program.

Aside from the substantive themes treated by these works, what do you see as the trends that they manifest?

Christine Schöpf: On one hand, I find it interesting that the spectrum of animation has broadened considerably. This means that there’s a lot more beyond this current virtual reality trend. Take the prizewinners, for example. “Light Barrier” is essentially an installation. “Out of Exile,” on the other hand, is a VR work, albeit a most atypical one. Many works display the characteristics of an installation. There can no long be talk of “screen-based.” The sound work is also much more precise. I regard that as the major trend, this expansion, going beyond previous limits and considerably expanding the spectrum of traditional animation.

Since 1979, Christine Schöpf has been a driving force behind Ars Electronica’s development. Between 1987 and 2003, she played a key role in conceiving and organizing the Prix Ars Electronica. Since 1996, she and Gerfried Stocker have shared responsibility for the artistic direction of the Ars Electronica Festival. Christine Schöpf studied German & Romance languages and literature and then worked as a radio and TV journalist. From 1981 to 2008, she was in charge of cultural and scientific reporting at the ORF – Austrian Broadcasting Company’s Upper Austria Regional Studio. In 2009, Linz Art University bestowed the title of honorary professor on Christine Schöpf.

Juergen Hagler currently works as a professor for Computer Animation and Animation Studies in the Digital Media department at the Hagenberg Campus of the University of Applied Sciences Upper Austria. He became the programme coordinator for the Digital Arts master’s degree programme in 2009. Since 2014 he is the head of the research group Playful Interactive Environments with a focus on the investigation of new and natural playful forms of interaction and the use of playful mechanisms to encourage specific behavioral patterns. Since 2017 he is the director of the Ars Electronica Animation Festival and initiator and organizer of the symposium Expanded Animation.

Alexander Wilhelm (born 1973) is a designer and professor at the FH Hagenberg in Upper Austria. His company „The Visioneers“ does science visualistions and Interaction Design tätig. He teaches 3-D-Animation and Design in Film and Games at the FH Hagenberg and Art University Linz.

The 2017 Ars Electronica Animation Festival runs during the Ars Electronica Festival (September 7-11) in CENTRAL, OK Center for Contemporary Art and Moviemento. You can find out more about the symposium, as well as the past editions of Expanded Animation, at the Expanded Animation website. To learn more about the festival, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter and visit our website at https://ars.electronica.art/ai/en/.