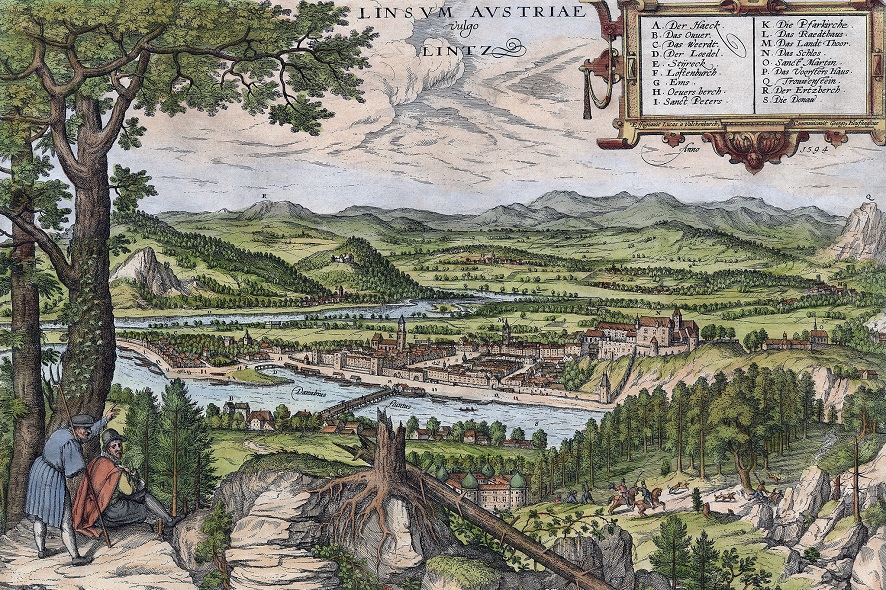

It’s the early 17th century. Linz is a small town on the Danube. Its outskirts are farm fields, and it will be quite a while until steel is produced here. Religious wars are raging throughout Europe, the Reformation is succeeded by the Counter-Reformation, and one doesn’t have to travel far to witness the horrors of the Thirty Years’ War. Ultimately, peasant revolts break out in Upper Austria. Amidst this maelstrom, astronomer Johannes Kepler moves to Linz.

How must the city in that day and age have appeared to the famous scientist? At the next Deep Space LIVE on February 22, 2018, Maria Altrichter of the Municipal Archive will take a look back and accompany us in Kepler’s footsteps through Linz. In this interview, she tells about her upcoming talk, her work at the archive, and why Deep Space 8K consistently opens up new views of old documents.

Maria Altrichter. Credit: Vanessa Graf

Your talk is about Linz in Johannes Kepler’s day. Why is this period so fascinating?

Maria Altrichter: Well, every historical period is interesting—in the early 17th century, this is due above all to the conflicts triggered by the Reformation. First the Reformation, then the Counter-Reformation—which, of course, also manifested themselves in Linz. The aristocracy and the upper class were the ones most strongly drawn to Protestantism and into opposition to the princes who reigned over this land. These disputes went on from about 1550 to 1626, when the Peasants’ Wars put an end to them. These developments provided plenty of room for conflict and were the lead-in to the Thirty Years’ War that began in 1618 with the Defenestration of Prague. Although Linz was not a particularly large city, these events had consequences here. The estates became more self-confident and built the Landhaus, a building of their own as opposed to the Schloss (castle). They also established the Landschaftsschule that offered positions to scholars, Kepler among them.

What did Linz look like then? What traces of that day and age are still visible here today?

Maria Altrichter: Despite being a province capital, Linz was not an especially important city. Steyr, for example, was much more significant from an economic standpoint and much larger. Linz was generally a small city. Today, you can still see the structure of the city walls from that time, which extend from the Promenade via Graben to the perimeter of Pfarrplatz and then along Donaulände, and the façades of the houses there all the way to the Schloss. Everything within the walls was the city; the rest was part of the Vorstadt (suburb), which officially belonged to Linz, though the burghers living within the walls had more rights, whereby those were primarily of a commercial nature.

Today, you can still see Linzer Schloss, which was built around 1600. This was previously the site of a medieval fortress that Emperor Rudolf II had renovated into a deluxe castle. And it still stands in this form today, though it’s missing a wing, which burned down in the great fire of 1800. In its place, a new tract was added, a fourth wing. The Landhaus too was remodeled and repeatedly enlarged in the 1560s and ‘70s. These two buildings truly are products of the age of Johannes Kepler and are still highlights of the cityscape—at least the downtown. The city as a whole is much bigger.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

Your talk in Deep Space will be accompanied by images from that time. What’s it like searching the source material for such ancient documents?

Maria Altrichter: Most of the images aren’t ours, since our archive doesn’t include such old images. What I’ll be screening was graciously made available by the NORDICO, which has a huge graphics collection, as well as by the Landesmuseen. Four years ago, the Linz Municipal Archive published a book entitled “Linz – Views from Six Centuries” in which we made an effort to depict Linz using the very oldest views of the city, and with those from the 18th and 19th centuries as well as contemporary photographs, but there are hardly any images from the time of Kepler that really paint an informative picture. The earliest ones on which you actually see something and really recognize the city are from the 1550s. So it was relatively easy to choose since the selection is so limited. On the other hand, they’re truly fascinating images, especially if you imagine this from the point of view of that time! These are highly detailed drawings of the city made with absolutely minimal means of artistic expression—for instance, there were no drones to provide a bird’s-eye view of the city.

How are the Archive’s data and images used?

Maria Altrichter: For one thing, we give talks like this one in Deep Space. Aside from that, the images are used for historical research. A few users come to us very frequently and do extensive work on urban historical topics. They’re glad to have access to our sources. There are also those who are motivated by their own personal interest to visit us and partake of this great storehouse of material. Most of it is analog information. We’ve digitized some of our holdings and we even have some data that originated in digital form, but it’s mostly analog. There are also many people who come to do genealogical research with the data that we’ve accumulated over many decades and have digitized so that it’s possible to do database searches with them. Our mission is to serve as the city’s memory so we have to conserve everything that’s important, legally or historically relevant material, real documents and images of the city. If nothing is retained, legal certainty dies. Plus, a lot of our history vanishes if there’s no place that serves as a repository of memory, that stores and preserves things. And if nothing is set aside, there’s no process of reflection. Our job is to prevent that.

Credit: Archiv der Stadt Linz

What’s the attraction of peering far back into the past in such a modern facility as Deep Space 8K?

Maria Altrichter: I find the Ars Electronica Center and the Linz Municipal Archive make sort of an odd couple at first glance because our respective historical interests don’t really match. But in fact, it’s really amazing to behold documents like city views displayed in such high definition on such a jumbo-format projection surface because you get to see details that otherwise go unnoticed. This happens time and again when we project an image that we’ve examined a hundred times at work and are thoroughly familiar with. But when you blow it up so large and zoom in on the details, you recognize things you never noticed before. This is incredible; it’s absolutely mind-blowing and we’re delighted every time it happens! And the combination of our historical themes and the young audience is terrific. This mix of young and old, historical content and modern presentation, is quite enthralling.

Maria Altrichter was born in 1980 in Upper Austria and studied History and Archive Science in Vienna. Since 2009, she works as a scientific archivist at Linz Municipal Archive.

The Deep Space LIVE entitled “Linz during the Time of Kepler” is set for February 22, 2018 at the Ars Electronica Center. More info is available on our website.

To learn more about Ars Electronica, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter, and check us out online at https://ars.electronica.art/news/en/.