Guanaquerx by Paula Gaetano Adi, winner in the Artificial Life & Intelligence category 2025, reclaims the Andes as a site of resistance and reimagines robotics as a tool for planetary liberation.

What if the first robot to cross the Andes wasn’t built for conquest—but for liberation? Guanaquerx, created by Argentinian artist and theorist Paula Gaetano Adi, reimagines robotics as a collective, poetic, and insurgent act—far from Silicon Valley’s narratives of optimization and control. Modeled after the guanaco and inspired by Andean cosmotechnics, accompanied by an army of artists, engineers, local muleteers, and 58 mules and horses, guided by local knowledge and ancestral memory.

Part science fiction, part pilgrimage, and part political gesture, Guanaquerx does not seek autonomy in the usual sense. It is moved by people, animals, and histories that modern technology often forgets—or erases. At the heart of the project lies a radical question: What does it mean to liberate a robot—and what would a truly emancipatory technology look like?

Winner of a Golden Nica at the Prix Ars Electronica 2025 in the category Artificial Life & Intelligence, Guanaquerx will be presented at this year’s Ars Electronica Festival in Linz. We spoke with Paula Gaetano Adi about this special project of liberation, robot comradeship, and why no machine ever walks free alone.

What is meant by “robot liberation” ? What does it actually mean to liberate a robot? What kind of alternative technological revolution is being envisioned here?

Paula Gaetano Adi: The idea of a robot liberation is, in many ways, not new. Since the invention of the term robot in the 1920s, robotic figures in science fiction have consistently been portrayed as beings in search of emancipation—electromechanical slaves whose narratives echo the histories of human enslavement and the struggle for freedom. From R.U.R. to Blade Runner, liberation for robots is either granted legally by their human creators or violently seized through apocalyptic rebellion and uprising. These stories repeat because the robot, by definition, is a figure of subjugation—created to serve, optimized to obey, and feared for its potential revolt.

Guanaquerx inhabits this narrative but also departs from it. It does not seek freedom by appealing to the legal frameworks of its human creators, nor does it overthrow its masters in a dystopian revolt. Instead, Guanaquerx enacts a different kind of revolution—a revolution not in the tech-world sense of rapid innovation or disruption, but in the original political sense: a break with the past to make possible a future grounded in freedom. Rather than reproducing the violent, extractivist logics of modern Western technoscience, Guanaquerx aims to enact a decolonial technological practice rooted in Andean cosmotechnics—one attuned to the earth, to relationality, to cohabitation with all beings.

The robot’s revolution we are proposing here is not about power or control, but about reimagining robotics itself. It invites us to consider machines not as instruments of domination, but as comrades in the struggle for planetary liberation. It is a call to reclaim technology with a pre-modern, anti-capitalist imagination—a creative, poetic, and insurgent act that insists another technological future is possible, yet to be imagined. Guanaquerx, the idea, begins with the premise that liberation is always already an existing possibility that remains unfinished and unmet, yet sustained by images and practices that connect us to each other and to the planet.

How does Guanaquerx engage with the historical memory of liberation in the Andes?

Paula Gaetano Adi: Guanaquerx’s journey is a deliberate re-enactment of one of the most significant and underrecognized liberation odysseys in Latin American history: the 1817 crossing of the Andes by the Ejército de los Andes, led by General José de San Martín. This was not just a military campaign—it was a collective act of resistance and self-determination that brought together an unlikely coalition of 5,200 people and over 10,000 animals. Around half of the army consisted of African slaves who were granted freedom in exchange for their participation. The rest were local Indigenous, mestizos, “baqueanos”, “arrieros”, and Chilean exiles, many of whom knew the Andes intimately and led the way through harsh terrain and perilous passes. Even women actively participated, though they were not allowed to enlist in the army—they prepared provisions, donated their jewelry to fund the campaign, sewed uniforms and flags, and some even disguised themselves as men to join the crossing.

It was an operation of profound ingenuity and courage. It relied not only on San Martín’s vision and long-term plan to liberate all of South America, but on the knowledge, endurance, and sacrifices of the people of the Cuyo provinces—and practically without any support from the newly formed Argentine nation in Buenos Aires, which at the time failed to see the importance of also liberating Chile and Peru from Spanish rule.

This is the legacy Guanaquerx is engaging with. On January 19, 2024—exactly 207 years later—we followed the same path through the Paso de los Patos, one of the highest crossings between Argentina and Chile, now used only by local goat herders and arrieros. It was the same route San Martín had chosen to cross and surprise the Spanish forces—so difficult that the enemy never imagined a full army could make it through. Choosing that pass was not only a tactical decision, but also an act of radical imagination, determination, and faith. It’s worth noting that this route also overlaps with the southernmost stretches of the ancient Inca Road, once used by the chasquis, the empire’s messengers.

For me personally, this was also a return home. I grew up in this region of Argentina, and every year people from my hometown retrace the crossing as a kind of pilgrimage. The terrain is still harsh and unforgiving, but the journey continues as a living act of remembrance and collective memory.

By embedding our robot into this story, we aimed not only to honor those who carried out the first wave of decolonization in South America, but also to insist that new stories of freedom—especially those now entangled with technological futures—must be imagined alongside past and ongoing liberation struggles. Guanaquerx invites us to think of technological emancipation as part of a broader history of resistance—one grounded in Indigenous, Black, and rural knowledge systems too often excluded from dominant narratives of progress and innovation.

The robot is carried by animals and humans — what does that say about its liberation?

What is the symbolic significance of the robot not moving autonomously, but instead being moved through collective effort?

Paula Gaetano Adi: It’s symbolic, yes—but also literal. There’s no robot today, quadruped or biped, that can autonomously cross the Andes. Not one. Not for seven days straight, across rivers, steep cliffs, mud, sand, loose rock. But that was never my concern—or the concern of the local community. They didn’t doubt it for a second. They always knew we could rely on mules and horses. I don’t think this was something the engineers ever thought about as a solution.

I remember one of our early meetings. I showed them footage of the terrain and they looked at me, half-joking, and said, “Paula, we’re working on a quadruped robot, not a drone.” That’s when I told them: “I know—I never said it needs to walk across the Andes on its own.” I’m pretty sure they thought I was completely out of my mind.

In 2023, a year before the actual crossing, we organized a preliminary expedition. One of the Silicon Valley lead engineers joined. The moment we got on horseback, just a few steps in, he turned to me and said, “Our robot can’t walk here.” And I said, “Exactly. I didn’t bring you here to fix your robot or debug your code—I brought you here so you could see with your own eyes that we can do it.” That’s when we started, for example, designing the albarda, the pack saddle, to fit the robot. That first expedition was crucial for the non-local team to truly understand what we were up to—to get familiar with our history, with the place, and with the overall mission.

So yes, the robot’s liberation is collective. Simply because liberation is always a collective act. And this was always central to the project. It took 58 mules and horses and 30 people to move a two-foot-tall guanaco-machine across the Andes: baqueanos, muleteers, engineers, videographers, a cook, a doctor—who carried the robot and cared for it, day and night. But that was just the surface. Behind them were nearly 100 others: the roboticists who built it from scratch; the locals who planned the expedition and built the pack saddles; teenagers who built the weather station; textile weavers, bamboo artisans, a luthier, historians, seamstresses, web programmers—and my family back in San Juan, keeping the entire thing afloat.

The expedition lasted seven days. But the operation of liberating a robot took two years. Two years of work, care, faith, and invention. It took an “army” to put into motion a different kind of cosmotechnics—one that doesn’t separate the machine from the land or from the people, and insists that freedom isn’t a state to be conquered but something forged—over time, with others, and in relation.

In what way is Guanaquerx itself an act of liberation?

Or is the project rather meant to inspire others — to awaken a desire for freedom and resistance?

Paula Gaetano Adi: That’s an interesting question. I would say that for me, Guanaquerx already felt like an act of liberation—because it meant designing, building, and programming a machine outside the constraints (and the violence) of modern technology. Outside the mandates of Western techno-science, and beyond the rationalist, instrumental traditions that form the foundation of AI and robotics.

But it’s also important to remember that this is an art project. And art, in its very nature, is liberatory. That’s one of its most powerful roles. It creates space—space to imagine otherwise, to act otherwise, to feel otherwise. That sense of freedom was always embedded in the work.

I’m not sure if it will awaken a desire for freedom and resistance in others. But what I do know is that it showed—through action—that another kind of technology is possible. That another technical imagination is possible. And in that, I think, it became an act of liberation.

I also like to think of Guanaquerx as a kind of science fiction project, in the sense that Donna Haraway describes. Science fiction not just to imagine the future, but to analyze the present differently. Fiction science as political theory, feminist theory, techno-science theory, as Haraway taught us. Our robot still exists in a space of speculative fabulation—but it’s a fabulation that crossed the Andes. That was built. That walked on the land. That broke down many times. That failed. So it’s not entirely fiction either, like in film or literature. We built a fiction of another kind. We imagined and enacted an alternative reality. In that sense, our science fiction became both a lived reality and a strategy: a tactic to refigure technology beyond anthropocentrism and coloniality.

How did local communities respond to the robot?

Was there resistance, curiosity, a sense of connection? What kinds of reactions did the project provoke on the ground?

Paula Gaetano Adi: The local community was not only involved; they were proud and deeply engaged throughout the entire process. We didn’t just show up with a robot—we worked with the community well in advance. More than 75% of the entire team were local people from Argentina. From the beginning, it was a core premise of the project that we weren’t importing a robot to deploy in the Andes—we were building one that could emerge from there, that could speak to us, to the people of the region. At the same time, it was never meant to be something purely local. To me, it was important that it remain a hybrid—something that could exist in multiple worlds at once. A kind of mestizo. I was very interested in showing that technology developed in the traditional centers of tech innovation could be re-appropriated, subverted, and used for entirely different purposes. I think that intention resonated with the community and helped them take ownership of the project. It was always our “guanaquito”—people rarely referred to it as “the robot.” And that’s the thing about robots: they can easily be imagined as alive, and that created a unique sense of empathy and connection that was fundamental to how the community engaged with it. I think it really mattered that the robot was shaped after the guanaco. Everyone here is familiar with this animal. There was a sense of pride that this was the form the robot took—a species that lives only in the high Andes.

But also, the engineering team from the U.S. traveled to San Juan on several occasions, staying for almost a month each time. Together, we assembled the robot in Argentina—first in my studio in San Juan, and then in the town of Barreal, our local base at the foothills of the Andes, where we conducted testing and trial runs. During those visits, the engineers met the local team. For example, they met the group of teenagers who had been building the robot’s weather station, and about a month before the official expedition, they all brought the robot together to the Sanctuary of the Difunta Correa—a regional spiritual landmark—to receive protection for the journey.

In the lead-up to our departure, local newspapers and radio stations came to cover the project. The town of Barreal organized a celebration, and the traditional dancers of the Virgen de Andacollo, the local patron saint, came to perform alongside the robot. These dancers were relatives of the women who had worked on the robot’s textiles and of the baqueanos who joined us on the expedition. In many ways, the entire town was mobilized. There was a shared sense of accomplishment that Guanaquerx’s crossing of the Andes was made possible through the labor, knowledge, and care of the people who live there. Everyone contributed. That made all the difference.

At a time when AI and robotics are often tools of exploitation, environmental destruction, and colonial futures: How does Guanaquerx offer a poetic counter-image — one in which robots are no longer instruments of domination, but become comrades in the struggle to heal the planet?

Paula Gaetano Adi: Guanaquerx was never conceived as a tool. It wasn’t built to optimize, extract, or control. Guanaquerx doesn’t promise salvation or efficiency. It doesn’t claim to fix the planet. What it does is open up space to imagine how robots might exist differently—not as servants, not as threats. A counter-image, as you call it—of poetic resistance. A kind of resistance that allows us to redirect our fears. I don’t think we should fear that machines will go out of human control and take over the world, as mainstream media often suggests. The real danger lies in how—and what for—we produce and operate technologies in the first place. Robots are our creation—and like anything we create, they shape the conditions in which we live. Technology designs us back. If we design free robots, they’ll design us free. That’s the kind of solidarity and camaraderie we’re proposing here.

Who would have imagined that the first robot to cross the Andes wouldn’t be working for the international mining corporations that currently occupy the region extracting gold and other metals—but instead, an art robot reenacting past struggles for liberation? A guanaco rover that reactivates the local mythology of the “Yastay”—the guanaco protector of the Andes, guardian of animals, son of the Pachamama, and brother to the wind. That’s the kind of resistance Guanaquerx is putting forward. In a world where robotics is too often aligned with domination—through surveillance, militarization, extraction, or fantasies of colonizing other planets—Guanaquerx shows us that another kind of technology is possible.

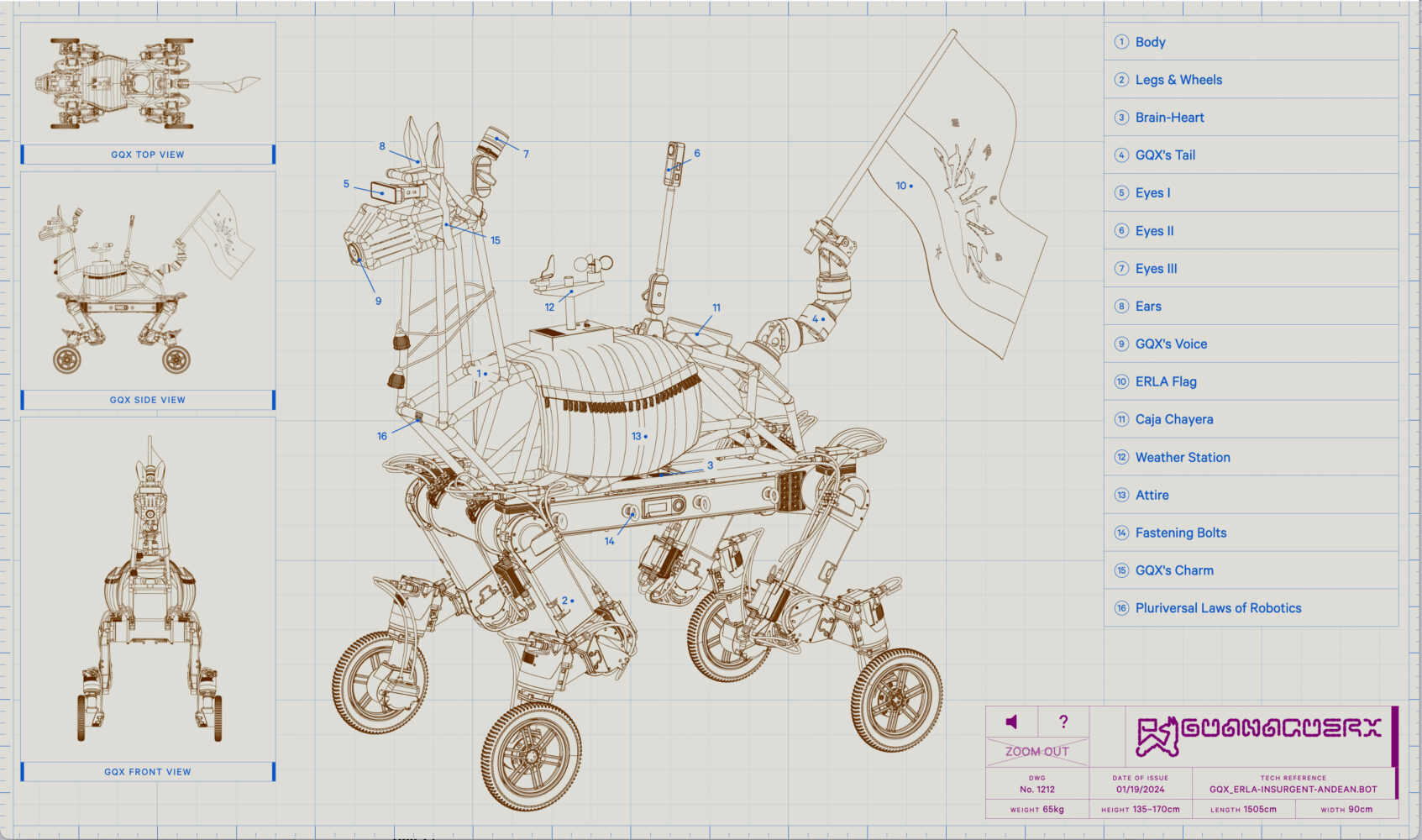

For that reason, and as a way of concluding our long journey and pilgrimage, we released Guanaquerx’s “emancipatory declaration” at 4,500 meters high, with Mount Aconcagua bearing witness: “The Pluriversal Laws of Robotics”—a direct rewriting of Isaac Asimov’s original laws, meant to challenge the human-centered ethics and instrumental logic they uphold, and to inaugurate a planetary ethics for how we make, imagine, and live with robots.

Paula Gaetano Adi’s Guanaquerx will be presented at the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, September 3–7, 2025. As a Golden Nica winner of the Prix Ars Electronica 2025, the work will be featured in the dedicated Prix Exhibition at Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz—the most important

exhibition of the festival. For the latest updates on this and other program highlights, visit our festival website.

Paula Gaetano Adi (AR)

Paula Gaetano Adi (AR) is an interdisciplinary artist and scholar working at the intersections of robotics, crafts, video, and performance. Her practice draws from studies of technoscience, decoloniality, and artificial life, enacting speculative scenarios where machines become sites of poetic resistance. Her work has been widely exhibited in museums, conferences, and festivals across Europe, Asia, and the Americas, and she has received numerous awards and honors. Gaetano Adi is currently a Full Professor of Experimental & Foundation Studies and Computation, Technology, and Culture at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).