The connection between fashion and technology consists of a lot more than smart clothing and wearables. This is also a matter of new processes, innovative materials and unprecedented forms. There’s also a place here for critique of technology—at least, at Linz Art University’s Fashion & Technology (FAT) program that’s occupied with the interface of precisely these two domains.

Now, this theme is being scrutinized at the 2018 Ars Electronica Festival. An exhibition will showcase creations by FAT students, and a Platform Event entitled “The Politics of Fashion: Fashion as Social Bot” will discuss what technology and fashion have in common and what sets them apart. Fashion & Technology program director Christiane Luible tells us more in this interview.

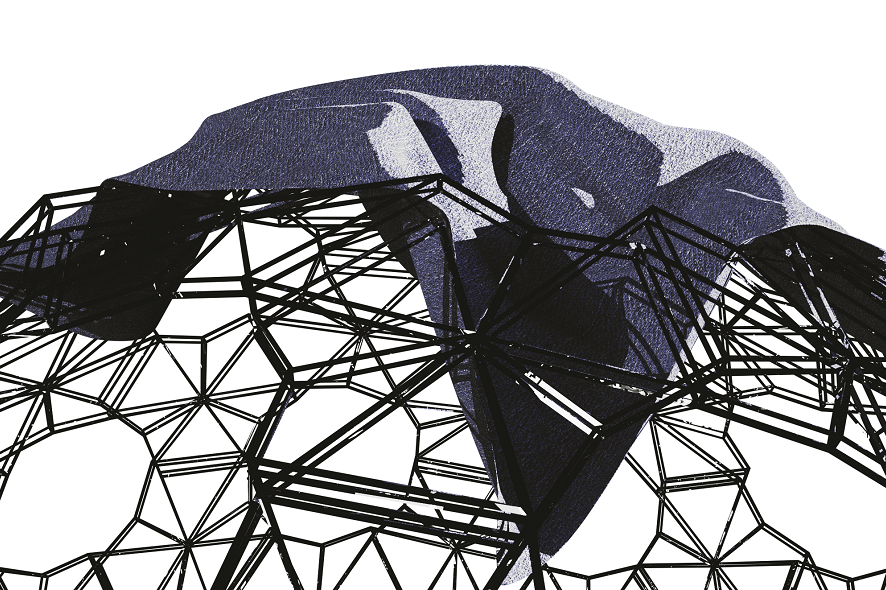

Generative Rendered Design. Credit: Viktor Weichselbaumer

The first class to complete the Fashion & Technology bachelor’s degree program will be presenting their final projects, so this would be a good occasion to say a few words about this new program.

Christiane Luible: We launched the program in winter semester 2015. The course of study lasts seven semesters, but now, after six semesters, many undergrads have already completed their practical work. After that, there’s also a required paper, which means that after turning in the practical work in July, the students have a whole semester to write their theoretical work, maybe to supplement their practical work and , above all, to give some thought to the presentation of their works. Among these practical works are five that take a very interesting approach to this aspect of implementing technology. Now, we want to sneak-preview them at the Ars Electronica Festival.

Why, actually, offer fashion studies in Linz? Linz isn’t a fashion industry hotspot…

Christiane Luible: Before this program was established, a commission of experts convened to decide whether this made sense and, if so, how the program should be oriented. Indeed, Linz isn’t a fashion center but it is the home of Ars Electronica and industries that are strong in the fields of automation, mechatronics, digitization, additive production processes and fiber & material technologies—and thus, technologies that could play a key role in the future of fashion. Accordingly, the commission came to the conclusion that it did indeed make a lot of sense to offer fashion studies here. In Linz, there’s a high concentration of technologies with great future promise, and that’s exactly what our program is oriented on. But this isn’t only about innovation and new technologies; we work with traditional textile technologies too—after all, with the Textile Center in Haslach and Lenzing Corporation, Upper Austria has a textile tradition of long standing. Our aim is a program that combines conventional and new technologies, and creating something new from this.

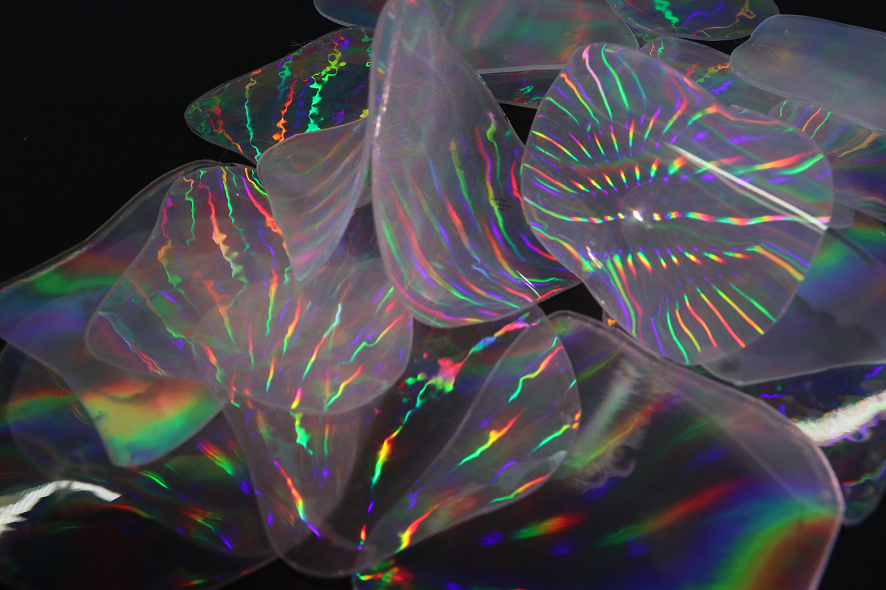

Visual Invisibility. Credit: Sara Kickmayer

When you hear Fashion and Technology, you immediately thing of wearables, but you have a different approach…

Christiane Luible: Exactly. A lot of people think we’re adding a little technology to garments and turning them into wearables—clothes that blink and do all sorts of other stuff. But we’re pursuing a different course. We want to combine fashion and technology in such a way that they condition each other. Fashion and technology should interact and blend in some way so that the outcomes are new processes, materials, forms or even reciprocal relationships and, ultimately, new aesthetics.

For example, we have two students who’ve taken leave of conventional analog fabric cutting and are using digital 3-D processes to generate garments. Even if these methods are already being used more intensively in other areas, they’re still new approaches for fashion. We work mainly with textiles and they’re very complex when it comes to a precise digital representation.

New materials are something else we emphasize. For instance, the students get started right away experimenting with bio-plastics or creating materials out of fungi. In our work with students, we call into question methods currently used in fashion. We try to develop new processes, materials and forms, and this is precisely where various technologies come into play.

Credit: Florian Voggeneder

A striking feature of these works is their confrontation with the body and the technology-saturated world. How does one reflect in terms of fashion on the media that envelope us?

Christiane Luible: The material, the structure and the form are the traditional design elements in fashion. If a garment reacts to the wearer’s body or his/her surroundings, then this interactivity makes another design element available to the fashion designer. However, we don’t associate this interactivity only with electronics—for instance, this could occur on the biological or mechanical level.

The round-table discussion in conjunction with the exhibition will deal with precisely these topics: “The Politics of Fashion: Fashion as Social Bot.” What awaits us?

Christiane Luible: Inherent in a consideration of what clothing can do is actually the question of how the human being can be perfected. Here, we get into media theory a bit—clothes constitute tools; one can monitor the body, one’s bodily functions and the resulting data in order to improve performance. At least that’s how it’s perceived. In reality, this has nothing to do with optimization. Other issues predominate in fashion now, and that’s what we want to bring out in this discussion.

The world of fashion is going through a fundamental transition at the moment, perhaps the greatest in its history since the Industrial Revolution. The fashion industry is #3 in the use of resources; only the construction and food industries use more. Fashion is a very labor-intensive sector. Clothes are sewn by hand in low-wage countries. The seamstresses’ wages are so low that they’re an immaterial factor in the cost accounting. The fashion industry has to remake itself.

Today, new technologies promise to radically change fashion and the garment industry. But, for starters, that has nothing to do with optimizing the human body. We want to juxtapose the usual suspects—wearables, smart clothing, body optimization—to the fundamental makeover of the fashion industry.

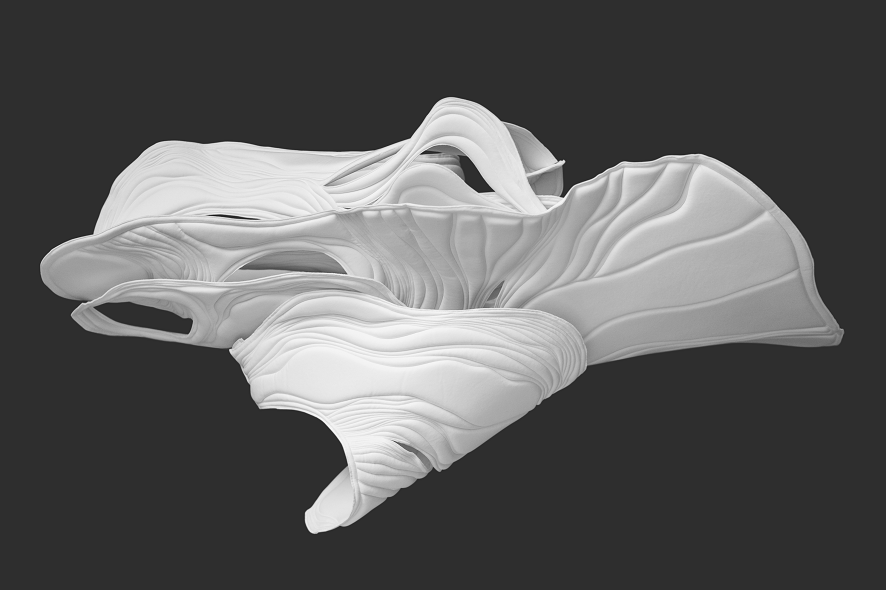

Sculpting Identity. Credit: Nina Krainer Photo: Esthaem

This is going in the direction of the festival theme, Error – the Art of Imperfection …

Christiane Luible: Quite so! This is right up our alley. Like I said, the fashion industry is going through a radical change now, and this is something we’ve been speaking about for the last 3-4 years, though I see this as a longer-term process that will unfold over a decade or two. Nevertheless, this process is underway and we want to use precisely such a platform to have input into how it progresses. I think this is how it is in a discussion taking place here in Linz precisely because Linz isn’t a city known for fashion. A festival that’s all about art and media technology goes perfectly with this mood that things are changing in a big way in the fashion industry. The point is to create an alternative presentation platform for projects and discussions.

The trend towards deceleration, retreat, being conscious of sustainability is strongly evident right now, and not only in the fashion industry.

Christiane Luible: Sure, and that’s precisely why I find it so important to host this dialog at the Ars Electronica Festival. Now, there are also many research projects going in this direction, and conferences and symposia on this topic. Nevertheless, when it comes to fashion and technology, talk often centers on this traditional context of wearbales. I say traditional, although this too is actually new, but, for us, this is a fashion concept that we want to go beyond. There’s a much more exciting approach to fashion and technology, and we can make an impact on it. It’s good to host a discussion about fashion at a media art festival and to create another exhibition platform that’s not subservient to the existing presentation system of fashion.

Credit: Florian Voggeneder

So, what can we look forward to at the Fashion & Technology exhibition during the Ars Electronica Festival?

Christiane Luible: There won’t be any fashion collections. Instead, you’ll see interesting developments in materials and forms, and new processes.

Nina Krainer, for example, utilizes mostly analog processes in her work. When you see her objects for the first time, you might think they were 3-D printed dresses, but her works are the result of purely analog methods and fine needlework. Nina Krainer’s aim thereby is to bring out the value of analog processes in a digital world. Students in our program can do this kind of work too—the important thing for us is that they take a stance towards technology. You don’t have to rush headlong into new technologies.

Sara Kickmayr is interested in micro-structures, molecular technology and its aesthetics. In cooperation with the Profactor Company, she examined micro-structures and used a nano-printer to print them onto material. Her work also shows that one semester isn’t enough to really become skilled with a new technology, to go deep enough into it to initiate new developments.

Another student, Mirela Ionica, is doing research on simple possibilities to make use of the effects of natural forces and phenomena in the design process. Gravitation is a fundamental force of the universe. It’s a strong, attractive force on a large scale, and a weak force on a small scale, on the atomic particle level. This project begins with simple silhouettes and forms, with are then subjected to analog and digital distortion.

Julio Escudero poses the question of what happens when he superimposes the form of his body on his surroundings. His work opens up lines of communication between body and clothing, clothing and surroundings, body and surroundings, whereby the exchange of information between analog and digital methods is the basis of his work.

A group of students headed by Michael Wieser is completely rethinking the steps that go into the development of a piece of clothing. To accomplish this, they meticulously reconfigured software originally written for other applications. The result is a new process chain that’s unprecedented in fashion. We don’t show the entire process chain; instead, there’s a segment, a virtual model by means of which festivalgoers can experience generative design via visual and haptic feedback.

Christiane Luible is the director of Linz Art University’s Fashion & Technology program. Her work focuses on practice-oriented design research in the fashion design field. In doing so, she concentrates on 3-D modeling and virtual simulation of fashion, and the influence of digital media on the fashion design process. Christiane Luible studied Fashion Design at the School of Design in Pforzheim, Germany and at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. After earning an MAS in Graphics Communication at Ecole Polytechnique in Lausanne, Switzerland, she got her doctorate at the University of Geneva’s Miralab with a dissertation on virtual clothing simulations. She has been honored with several international design prizes including the Lucky Strike Junior Design Award and the F.I.T. Critics’ Prize, and has worked on such major European clothing research projects as E-Tailor, Leapfrog and Haptex.

The exhibition of creations by Fashion & Technology students will run throughout the Ars Electronica Festival September 6-10, 2018 in POSTCITY Linz. “The Politics of Fashion: Fashion as Social Bot” round-table discussion is set for Saturday, September 8th from 14 to 15:30 on the Workshop Stage.

To learn more about Ars Electronica, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter, and check us out online at https://ars.electronica.art/news/en/.