It’s a period of melancholy and farewell. A very special era in the history of the Ars Electronica Festivals comes to an end with the Big Concert Night, which will be staged for the last time in the impressive train hall of the abandoned Postal Distribution Center at Linz’s main train station. From a diesel locomotive that drove into the concert hall with spectacular lighting effects, to a gigantic industrial robot that accompanied the dancers’ choreography with the utmost precision – spectacular productions like these will once again guarantee impressive uniqueness in the Train Hall (Gleishalle) for the fifth time this year.

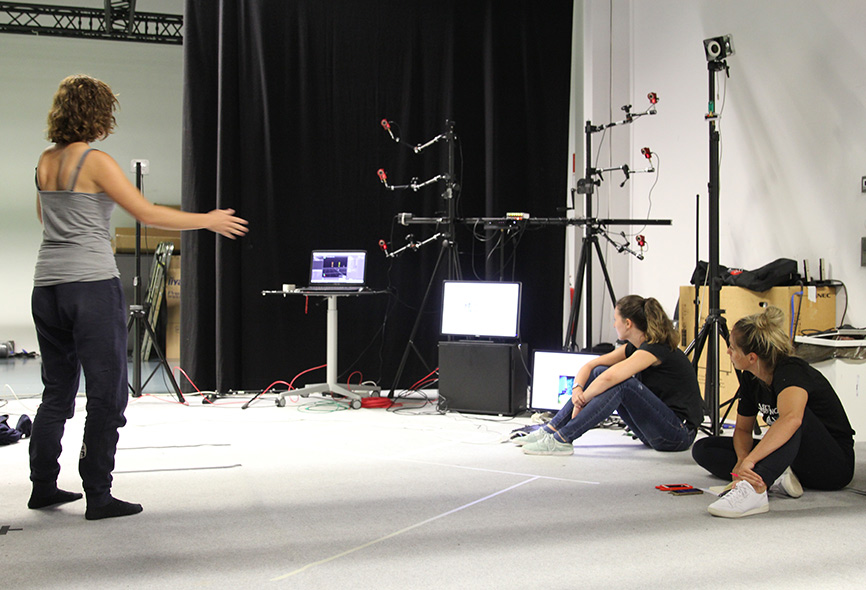

Gustav Mahler’s unfinished Symphony No. 10 in F sharp major will be at the centre of the Big Concert Night 2019, which this year will not take place on Sunday but on Friday, September 6, 2019, 7:30 PM. After Christian Fennesz uses excerpts from Mahler symphonies for his live performance with “Mahler Remixed”, conductor Markus Poschner will appear on stage to perform the last symphony together with the Bruckner Orchestra Linz – accompanied by dancer Silke Grabinger and several KUKA industrial robots, which will again be controlled by the Ars Electronica Futurelab in collaboration with Creative Robotics of the Linz Art University. The Japanese artist Akiko Nakayama takes over the impressive real-time visualization of the piece with “Alive painting”, and Ali Nikrang of the Ars Electronica Futurelab ensures that the audience can hear Mahler’s unfinished work to the end thanks to artificial intelligence. Ryoichi Kurokawa and Moritz Simon Geist finally make the transition to the subsequent Ars Electronica Nightline. We are excited! Information about the tickets can be found on ars.electronica.art/outofthebox/tickets.

The video shows a short compilation of the Big Concert Night 2018.

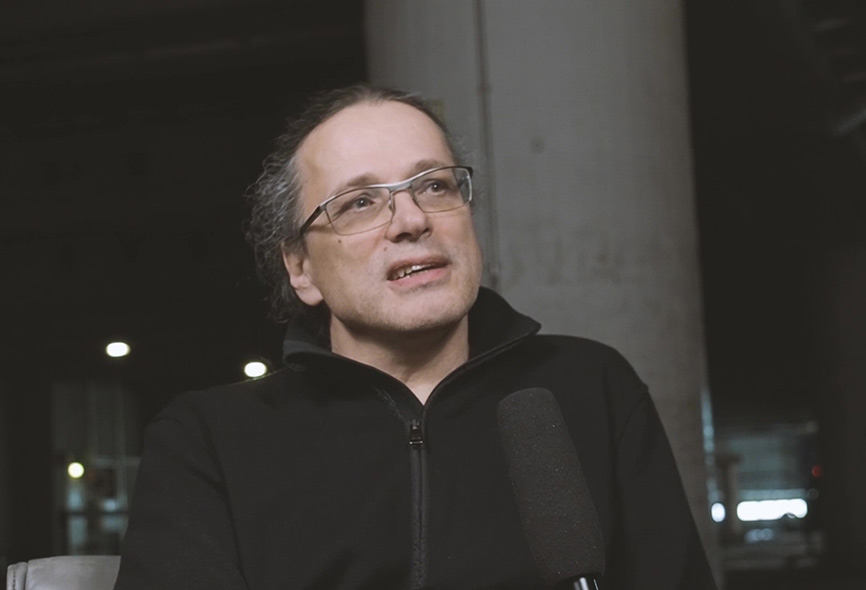

But back to POSTCITY. How does it feel to sit here after almost a year in the middle of the still empty POSTCITY track hall?

Gerfried Stocker: For me, the phase of melancholy and farewell begins. With this year’s festival we have the fifth year where POSTCITY has really become home. A pretty exciting home, which we had to rediscover and conquer from the very first day. A wonderful area that makes things possible that you wouldn’t think of otherwise. It’s a phase in which the place has also curated very strongly, because suddenly it has suggested event possibilities, ideas, projects that you wouldn’t otherwise come up with.

And this has also strongly influenced the Big Concert Nights of the last years, where we had to deal with an incredible enthusiasm, with an euphoria, which the hall evokes for all of us: just the railway tracks, which enter the hall here, where in Anton Bruckner’s 8th Symphony we were also able to run a diesel locomotive with great light effects in the middle of the concert hall. And then there is the perspective that this year we will have this place for the last time at our disposal. We will really enjoy and take advantage of that again!

The full interview can be watched on YouTube.

How does the Bruckner Orchestra Linz feel about playing in such an unusual place outside traditional concert halls?

Norbert Trawöger: If it is not a classical concert hall, then it is always the logistical questions that have to be clarified. But that will be clarified in advance – the orchestra will find its place, so will the audience. Going into new spaces means that the event and experience also gets a space. It is entering another threshold away from classical temples such as opera houses or concert halls.

We enter a place that many people didn’t even know before, because this postal distribution centre was a place of work. There is no concert hall in this dimension! This length and the tracks, the connection to the world outside, this is an incredibly fascinating place that offers so many possibilities. A place that opens up and that places the real thing that drives us, the making of music, in a different context of experience.

“This is what drives us, and this is more necessary than ever for people in the 21st century. To get people in who may never have heard an Anton Bruckner, a Gustav Mahler or another composer. I think that’s great.”

At the Big Concert Night 2019 we will hear Gustav Mahler’s 10th Symphony – how did the selection come about?

Norbert Trawöger: The music selection is very harmonious when we play the POSTCITY for the last time. Gustav Mahler’s 10th Symphony, his Unfinished Symphony, is an absolute final piece, the torso of a torso, where there is a lot of information, but the piece is not elaborated in any way. There are hints and different versions.

The piece was written one year before Gustav Mahler’s death. 1910 was a year of change that is perhaps comparable to the times we are experiencing today – a year where we are disoriented, wondering where we are going, what moves us, who moves us or who moves us ourselves? A fantastic music – a farewell and at the same time a new beginning, a dissolution.

Gerfried Stocker: The exciting thing about it is the time in which this music happens. When we think of this time, we know that it is before the outbreak of the First World War. When we think of the music of that time, it is now very old music. But this is also the time when Max Planck, Albert Einstein, formed their most important theories, which took completely new directions in science. Or Werner Heisenberg, who in the 1920s presented the uncertainty principle and his ideas. These are people whose cultural imprint is shaped precisely by these artistic ideas and forms of expression of the time.

Actually, this is a phase in which one begins to slowly bid farewell to industrial time again. This is the transformation that is about to take place, which will burn up the first half of the 20th century – with all the horrors that have finally happened. This confrontation – the simultaneity and non-simultaneity we see in there – is something where we can do a lot for our festival theme this year.

So the 2019 Ars Electronica Festival will also address one of these “phases of upheaval”?

Gerfried Stocker: When we say “Midlife Crisis of the Digital Revolution” with a wink, it points in a direction that is crucial for us. We are in the midst of a radical change, the consequences of which we can only recognize and assess vaguely. If we consider what social problems this period of upheaval has caused, the two world wars that have arisen out of it, all the abstrusities of National Socialism – then that is also something where we have to look at how we are now dealing with the upheavals that are coming with very alert and warning perspectives.

There are many analogies and parallelisms. We have a very exciting and profound new scientific development. In the entire field of biotechnology and genetic engineering, and in the field of artificial intelligence. This is similar to quantum physics, which is scientifically understood, but we still have to order it to understand it at all. At the same time there is a massive economic transformation. There are shifts in the balance of power in the global context. Everything could be transferred very strongly to our time.

How does art actually reflect this world around it? How do artists do that? There is an unbelievable potential in it that we can unleash in collaboration with the Bruckner Orchestra Linz, because we not only theoretically anticipate this experiment of the encounter of past and future, but it is like a test tube in a laboratory in which reflection on this clash and change can be experimentally tried out and takes place.

Many know the name Gustav Mahler – can you introduce us to the composer a little closer?

Norbert Trawöger: Gustav Mahler is a great Austrian sound figure – born in Bohemia (laughs), very Austrian. He conducted in Bad Hall at a young age. He is the world’s most famous conductor of his time, something like the Director of the State Opera, who had a decisive influence on the institution of the State Opera and also experienced massive resistance there. All very Austrian, I must say. In his last years he was chief conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. So really an international star of an unparalleled kind.

Today we are aware of the compositional work, it is played a lot. Mahler was something like a holiday composer. During the holidays, he made his way through his symphonic work, which is unique. Unique in his living out of the self. It is simply fascinating to see how an orchestra works out of knowledge, how it brings us invitingly into his biography. Into an ego that ultimately strives for salvation – to put it in a nutshell. You can’t escape that. This makes him actually a counterpart to our namesake Anton Bruckner, an opposition. Because Bruckner’s music is rather a feeling of togetherness. With Mahler one plunges into the ego and thus often very much into one’s own immediate ego.

The Bruckner Orchestra and the Ars Electronica have been going together for many years…

Norbert Trawöger: It’s a longer story! It is a stroke of luck that a historic tanker, which a symphony orchestra is, meets such a place of innovation as Ars Electronica. Art is all about constantly renegotiating things. It’s a new chance every day to live, to live into the works. Whether it’s from the present or the past, it’s a chance to place oneself in a social context.

“This thinking, researching, this being together on the road, the mutual breaking up and making spaces possible for each other, that is simply a stroke of luck.”

I’m glad we’re already living this intensively. In the future, it can only be planned that this will become even more intensive. And it will do so in order to increase the radius of possibilities and also to open and expand the scope for people.

Gerfried Stocker: From the historical point of view, it goes back to the year 2003, when we began to make these first concert nights. This is extraordinary in the sense of a stroke of luck: a media art festival that has its own orchestra. This mutual working up and further training of the possibilities and the ideas what one trusts one another and together to do.

If you look at the programmes of the past years, you can see this culmination. The presentation of experiments for the orchestra, i.e. new music, has always led to the understanding of the orchestra itself as an experiment: This encounter of orchestra and audience, of space and music, as it is possible in POSTCITY, this exploration of this very special space.

“You really have to imagine what an adventure it is for an orchestra to enter this train hall with this acoustics. This enormous willingness to conduct and live the experiment is something where this cooperation becomes something that radiates far beyond the festival.”

That is again in the sense of the test tube – there happens exactly what we need now in this time: To try out new things with each other, which are open to results and where it is also about what I can learn from it. How can I transfer this? That is the exciting thing! An orchestra project in one festival stands in a different field of discourse. If it’s a usual concert, you go there, go home again, and that’s it. Embedded in the festival, of course, is itself a motor for discourse.

So far, composers have been human beings – if you look at the development of artificial intelligence and transfer it to music: How do you think about that?

Norbert Trawöger: I am facing this in the first place without fear. Of course, an orchestra of this size is one of the last craft businesses. With currently approx. 130 musicians it is one of the last really big medium-sized craft businesses. In this dimension, there is no other institution in the city that has employed so many people who “only” practise crafts and where there is no automation in this sense. Orchestras can also expand…

I don’t know where we’re going. It’s simply a matter of looking at it together. Whether machines will write music in the future that touches us humans is possible – I don’t think that’s out of the question. Whether a machine or a person has written it, the question is actually: Is one emotionally moved or not? It remains to be seen whether a machine will be able to do that in the future.

If you break down the definition of music further, then music is actually “something made for human beings”…

Gerfried Stocker: This is also the basic theme of the special program “AI x Music” at the Ars Electronica Festival 2019. It’s all about the fact that music as an art form has been an incredibily rule-based one since its beginnings, and also one that’s totally characterized by tools. The history of instrument making and its development to the present day is an incredibly important part of how music and the perception of music have changed.

The question as to whether machines can compose music that touches us just as much as Mahler’s music does not go far, because we notice how music or any form of art in general is not just a process for creating a product, a work, an object, a symphony or the like. Art, and with music we all feel this much more deeply and directly, is also this continuous process of becoming human and the further development of our imagination and our ideal image of human. This is one of the very important tasks that art does, and music has an incredibly emotional background.

“Just as in the history of music, we will also show this at this festival, the tools and methods have constantly changed and were always up-to-date, so artificial intelligence will also be another element.”

So music is something essential for us humans?

Gerfried Stocker: It is exciting to think about it when it will happen that sometime in the morning the machine opens its eyes and says: “Ah, I am”. This magical moment, which we all have as a vision in our heads, that machines develop consciousness – what consciousness is, let us leave it at that. If machines develop a consciousness that is modelled on human consciousness, then of course they will need their own music in order to be viable.

We simply couldn’t live without music. That sounds pathetic now, but it is quite a decisive point of being human and becoming human. And maybe it will also be the case that music will play the same role for machines.

Now it is a very exciting field of discourse, because we associate many other questions with it: What role does the machine play in our time? Who masters and owns these systems? Do we come to the time of an early fundamentalism, where these machine systems are the latifundia on which serfs or peasants may move, but only under the rules of the owners of these systems? Are we getting something like self-determination? An awareness for the public that these spaces are also socially public spaces?

This can be dealt with wonderfully on the basis of the history of music and repeatedly leads to the core conflict: Human – Machine. Is this a conflict, must it be one? Can we perhaps not even understand that machines are something different, but that machine and technology are just as much a product of human creativity as the most beautiful paintings, sculptures and music we make? Mahler’s 10th is as much a result of human creative will and ability as is the supercomputer on which Google’s deep learning projects run.

“We must finally give up seeing the machine as the antithesis. The machine is part of our life, of our expression.”

To find out what else is happening around artificial intelligence and music, visit the AIxMusic Festival, which will be held in Linz from September 6 to 8, 2019, at the same time as the Ars Electronica Festival – read more about the program at ars.electronica.art/outofthebox/aixmusic/