Digital media and the networking possibilities it provides significantly determine a modern lifestyle—at least, they do for 3.2 billion of us. But what does it take to integrate the rest of humankind in this process? What was it like back in the old days, 20 years ago, when non-English speakers had no idea what “liking” was, television was a household’s prime medium, and spending money online was utterly inconceivable? For answers, we asked Marleen Stikker, co-founder of the Waag Society—she already got started sketching the emerging possibilities of such worldwide networking in 1994 in her project entitled “De Digitale Stad“.

And don’t forget—March 13th is the deadline for submitting works for 2016 Prix Ars Electronica prize consideration. Cash awards of up to €10,000 await the winners in each category. Details are online at ars.electronica.art/prix!

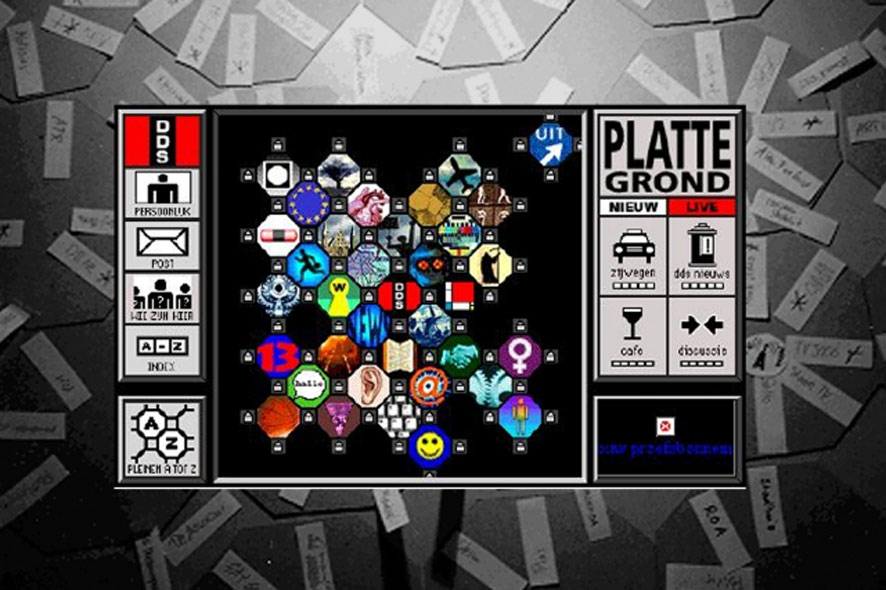

“De Digitale Stad” (DDS). Credit: Waag-Society

You’ve founded the “De Digitale Stad” (DDS), the first online Internet community in Europe, in 1994. Could you please tell us more about it?

Marleen Stikker: Back in 1993, the Internet was a black screen with a Unix prompt. There was a world of possibilities behind that screen, but nothing was accessible because of the secretive nature of its language and code. With De Digitale Stad, we appropriated that new technology for cultural and social use and opened it to society. The key to the design was an interface built around a metaphor (the city) that helped people to understand and make use of the Internet’s possibilities. Felipe Rodrigues and I designed the digital city in such a way that it would accommodate multiple uses: private, public, cultural, and political.

“It was a playground for experiments that we now take for granted. There was raw data and open city data; a smart TV that combined chat with live television (now known as the second screen); user generated content; profiles and avatars; online shops; and political debates.”Marleen Stikker

And it was all there in 1994. It proved that the Internet was an attractive social space for people to explore and help co-create its future. The Digital City inspired many tactical media artists all around Europe – like the Internationale Stadt in Berlin and Digitale Stadt in Vienna. It also helped the first Internet cowboys to convince investors to finance their attempts at world domination. From their perspective, the Internet was first for military purposes, then commercial, and then social. But that is wrong. The Internet did indeed begin as a military and academic research network, and then merged with the social global NGO network already in place in the eighties. That’s when it became social. Only after a few years later did commerce kick in.

FREE4WHAT Campaign, Credit: Waag-Society

Ten years after “De Digitale Stad”, in 2004, Facebook was founded. With 1.6 billion monthly active users it belongs to the biggest digital communities today. What do you think about these big social networks?

Marleen Stikker: Social networks are great, but most of them are based on extractive business models. Social relations and personal data are farmed and milked for profit. We warned people that they would eventually pay for free services one way or another with our FREE4WHAT Campaign. Unfortunately, they didn’t listen.

“The Internet creates a wicked problem. On the on hand, it empowers many to build civil societies and communities based on reciprocity. But, on the other hand, it makes it easier for companies and governments to infringe upon our sovereignty. “Marleen Stikker

I’m happy that Germany’s Federal Cartel Office is investigating Facebook for suspected abuse of market power over breaches of data protection laws.

Facebook Farewell Party in Amsterdam, Credit: Waag-Society

At the Waag Society, there is a project called “Facebook Liberation Army” which demands a free Facebook for everybody. What are the dangers or challenges for digital communities nowadays?

Marleen Stikker: With the Facebook Liberation Army project we organized a Facebook Farewell Party at the Stadsschouwburg in Amsterdam. The atmosphere was weird. For people who think they are on the “good side” (those who are concerned about climate change and animal well-being for instance), it is difficult to find themselves as a supporter of the “evil” Facebook Empire. For them, it felt as if we were trashing their party and making life more complicated. For the people who’ve actually left Facebook, it is difficult to find an alternative. The requirements are challenging: a business model based on commons principles, a smooth user-interface design, and a technical architecture that is both open and supports end-to-end encryption. There are some initiatives that may have one of the three requirements, but one that combines all of them doesn’t yet exist.

3.2 billion people are using the Internet by the end of 2015 globally but 4 billion people from developing countries still don’t have access to any form of a digital community. How can we face this digital divide?

Marleen Stikker: Interdoc was already addressing this divide thirty years ago. Clearly, it is not a good idea for Zuckerberg to give them a free Facebook version of the Internet. I’m afraid many of his kind will embrace these 4 billion human beings because they need growth figures. The question is not: will these people have access to the Internet? The question is: will they have access to the full and open Internet, or will they be trapped in applications that suggest they are the Internet? So, there is a lot of work to do for the open society, open hardware, open software, and open Internet movements in terms of bringing knowledge, skills, and access to these communities.

Marleen Stikker is a co-founder of the Waag Society and the current president of this foundation committed to nurturing experimentation with new technologies, art and culture. She’s been dealing with the possibilities of online digital communities ever since 1994, when she founded De Digitale Stad, the first digital city on the Web. In 2016, she’s serving as a Prix Ars Electronica juror for the second time.