Her (own) body is a field of experimentation for Lucy McRae, and her aim is to adapt it to extreme circumstances. It thereby becomes object of her observational documentary “The Institute of Isolation” – the project which she pursues under the aegis of the EU-funded project SPARKS. In an extensive eye-to-eye interview, the director and actress reveals how she is led to approach the topic of “body isolation” and how it can be helpful in terms of medical cure.

The “precursor” to the SPARKS project: Future Day Spa. Credit: Lucy McRae

Your latest project, “Future Day Spa,” shows the extent to which a human being can adjust to weightlessness-induced isolation in outer space. Now, your observational documentary produced in conjunction with SPARKS is entitled “The Institute of Isolation.” Is this a sequel to your prior work?

Lucy McRae: Especially over the last 12-18 months, I’ve been dealing with the subject of health and medicine from the perspective of science fiction. I use art as a means of conveyance, as a way to express something I don’t understand. Since projects are subject to a lifecycle and a deadline, serendipity has played a crucial role in the development of my current projects as well as the follow-ups. And since there’s usually not enough time to completely investigate all the discoveries made during a particular project, I simply take up all the still-open questions and turn them into my next film.

And at the screening of “Future Day Spa” at the re/code technology conference in Los Angeles, good fortune smiled on me once again. Among the 100 subjects I performed a bodily isolation test on, one person lying in a vacuum container exhibited an extraordinary reaction. As someone who actually shuns physical contact with people, he felt “embraced” by this form of envelopment—and thus very vulnerable. When he emerged and stood up, he hugged me, even though, as I just mentioned, he’s extremely stand-offish towards others. On the way back to the hotel, I did some research about this so-called touch syndrome and what it means for someone who is touched against their will. The brain secretes oxytocin, a so-called trust hormone that’s otherwise suppressed. So, the Future Spa program raised the question of how it might be possible to use the methods applied in it to treat conditions like agoraphobia, the fear of being touched, as well as autism, depression and anorexia.

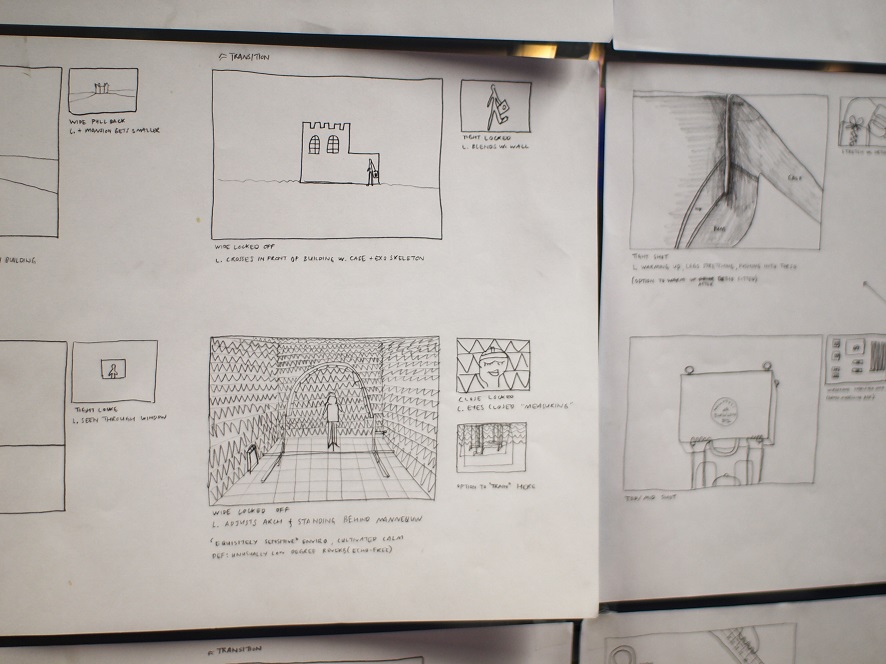

The storyboard to “Institute of Isolation”. Credit: Martin Hieslmair

A classic science fiction motif is the defiance of nature by human beings. What challenges or questions do you confront human beings with by means of technology?

Lucy McRae: I conducted interviews with 11 scientists and used this material as commentary accompanying the film. In response to the questions posed, they make their case based on their current state of knowledge—for example, on the growth of a fetus in the absence of gravity, an issue that just happened to come up during a bus ride with an economist and something that I’ve been dealing with intensively for two years now. Another core element of my work is the tendency to explore the limits of my own body—during my childhood, as a ballerina, as an athlete, and now through my art. Inherent in the preparations for space travel is the answer to the question of whether we human beings are capable of surviving in isolation, since that’s precisely what weightlessness is. Accordingly, this training is also preparation for a certain lifestyle that we now have to perform very exacting research on if we ever want to be able to survive somewhere beyond the realm of planet Earth.

Meeting and discussing the scenes with SPARKS-project manageress Claudia Schnugg. Credit: Martin Hieslmair

In your current project, you profile someone who’s interested in optimizing himself and this person goes through this process. Is the fundamental idea of perfecting human life in a scientific way or via technology simply all too human? Or is it our obsessive perfectionism that leads to this world that you often depict in such cool terms?

Lucy McRae: I too regard imperfection as beauty, but we human beings are geared towards striving for perfection and micro-managing all aspects of life. By no means do I intentionally create this aesthetic; it simply happens. I don’t even question why and I’m not seeking an answer. But isolation leaves no one cold. Oddly, I recently received an e-mail from a woman whose premises we wanted to use as a shooting location. In the e-mail, she gave an account of a friend who happened to be in an Intensive Care Unit and, due to her total paralysis, can communicate only by moving a toe. This means that, in her case, the human body and technology have completely merged. The way in which she expressed herself was so poetic; it was as if her friend were an island in this already-extant Institute of Isolation.

Preparing the 3-D Scan with Andreas Jalsovec. Credit: Michael Mayr

Is this a desirable world for the people affected by this, or are we just projecting this desirability onto a conception? And what happens when we ourselves are affected? Do we really want to be kept alive in this way?

Lucy McRae: It’s good that you’re asking about this… In the book “Evolving Ourselves,” which is the main source of inspiration for this film, the author goes into detail about how we redefine death. How we try to outfox and evade it, delay its arrival as long as possible, and sort of embalm the body to keep ourselves alive—and to do so with purely technological means. We do the same thing with delivering babies: 33% of all births are premature. Now, I’m not saying that that’s right or wrong; I’m just fascinated by it. If we carry out interventions like these in human genetics, and if they’re carried out by a computer engineer or a biochemist, then the borders between an engineer, an editor and a biologist are getting blurred. Then it’s just a matter of the production and staging of life. A portion of this film deals with the question of how our environment—that is, agriculture and architecture—can influence the human form of life. What is the architect’s role in this? And then it gets interesting when we imagine what happens when you point a laser at the brain to use rays of light to trigger fear or joy, and how that, in turn, influences how buildings appear. In the final analysis, you as an architect influence people’s feelings.

A still/scene of “The Institute of Isolation”, shot at Therme Bad Fischau. Credit: Claudia Schnugg

To what extent is your film “Institute of Isolation” based on hard facts?

Lucy McRae: The chapters of my film correspond to those of the book I mentioned before, and they, in turn, are based on scientific works, doctoral dissertations supported by footnotes. The film is an observational fictional documentary—that is, it’s not 100% science fiction, but it’s not 100% hard facts either. As I went about reading it, I was absolutely fascinated by everything that’s already possible but that most people don’t have the slightest inkling of. The core message is that it’s we human beings who are driving evolution forward, and not that human beings are subject to evolution as we’ve been led to believe by Darwin’s teachings. Just look at how technology has brought forth job descriptions. In other words, it’s very much conceivable that a little boy, when asked what he wants to be when he grows up, might answer: “An engineer on Mars.” This means that the fictional aspect is getting closer and closer to scientific fact. And since we soon won’t be able to determine with certainly which discipline is influencing the other more or less, the art aspect of this SPARKS project becomes all the more timely. The wonderful thing about this is that one can explain science using artistic means because the boundaries are so fluid.

The logo of the ficitional institute. Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Stylistically, the look of “Institute of Isolation” is reminiscent of Wes Anderson’s cinematic aesthetic. How do you explain to someone who’s not familiar with that director’s work how your films come across in terms of colorfulness, shooting locations and characters?

Lucy McRae: What I like above all is this loving attention to detail. Of course, what Wes achieves with the use of a lot of time and money is something I have to break down. For our part, we’ve already come up with some bizarre shooting locations that bring a tremendous richness of detail with them. For instance, we had only two hours to shoot in a hospital so every take had to be spot on. But that’s the novelty process in this project. I mean, normally, I sit for two days in a perfectly lit studio just to get 90 seconds of footage. This gives me a new feel for improvisation, and also with regard to reliability, the feeling that it’s working well with the people I’m collaborating with. But that was the thing about this project that appealed to me the most—to shoot a different kind of film for once, to apply a different form of storytelling.