“What sort of information trail do we leave behind—for instance, in a simple handprint—and what conclusions can be derived from this information?” These and other interesting questions are posed by Simon Krenn’s work entitled “In Vitro Typewriter” that will be featured in the TIME OUT .06 exhibition opening June 8, 2016 at the Ars Electronica Center.

Simon Krenn’s work is based on a hypothesis by Czech media philosopher Vilém Flusser, who maintains that all stored information must, at some point in the universe, flow back into the general stream towards entropy.

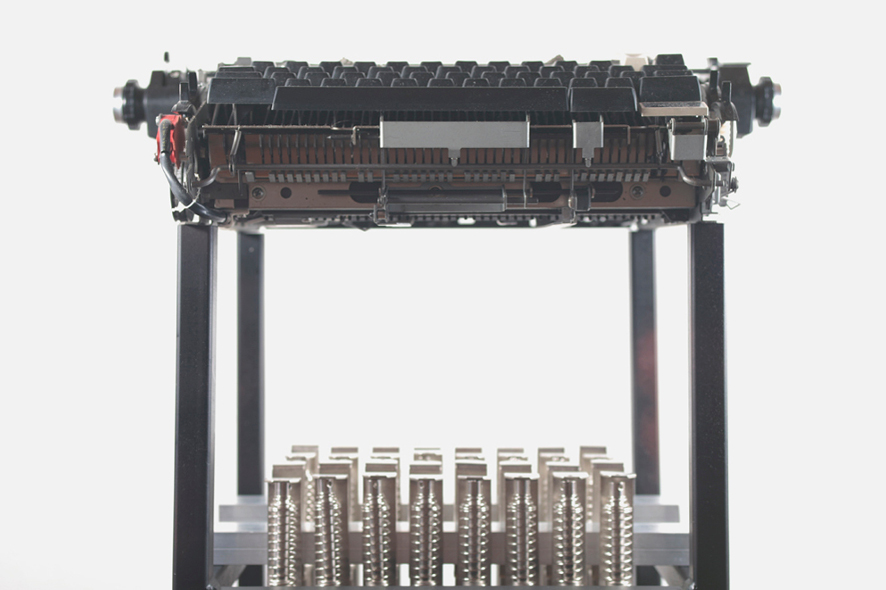

The “In Vitro Typewriter” consists of an old mechanical typewriter that’s connected via an Arduino interface to two Petri dishes containing agar culture medium in which colonies of microorganisms that were introduced by hand contact are growing. The growth of these colonies influences a text that is automatically written on the typewriter by a text recombination algorithm. The more the microorganisms proliferate and mutate, the more radically a scientific text about evolutionary biology and the principle of natural selection is modified—i.e. increasingly fragmentary text compositions are output by the typewriter.

We recently spoke to Simon Krenn, an undergrad in Linz Art University’s Time-based and Interactive Media program, about the precise interrelationship between his work and this hypothesis, and how he came to choose such a complex theme.

Photocredits: Simon Krenn

How did you come up with the idea that led to “In Vitro Typewriter”?

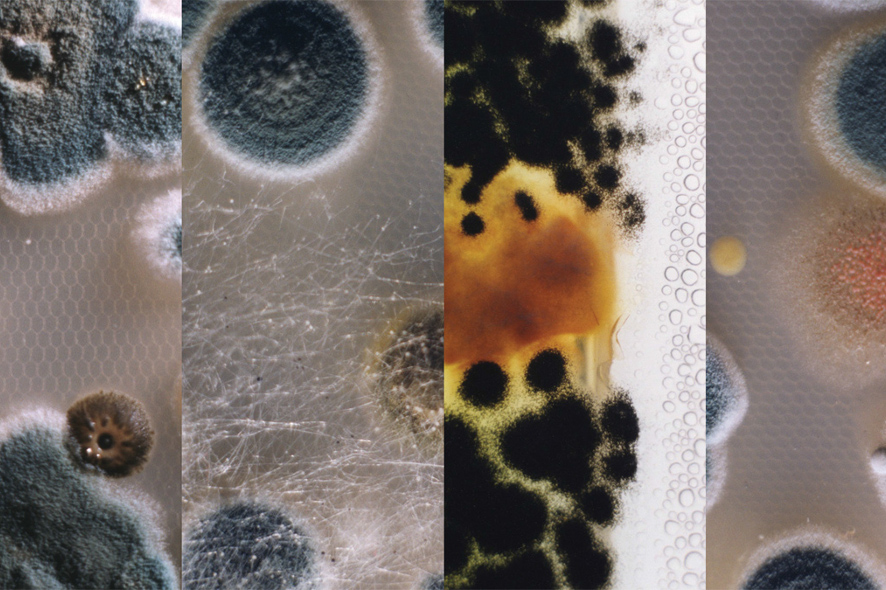

Simon Krenn: My initial concept was to develop a cybernetic hybrid machine composed partially of biomass and partially of electronic circuits. My aim was to derive a sort of logic from the various growth patterns and the morphologies of the cell colonies, which could then be applied in particular situations. Similar to Andrew Adamatzky’s PhyChip, a biomorphous CPU that’s controlled by a slime mold, Physarum polycephalum, I aimed to convert an existing biological system—i.e. the growth and development of simple bacterial cells—into small, intelligent entities. I’m currently working on a project designed to take this concept to the next level: the integration of a neuronal biofeedback system based on the growth dynamics of genetically modified microorganisms.

Your work is based on a hypothesis put forth by media philosopher Vilém Flusser. Please tell us more about how his ideas are connected to your work.

Simon Krenn: This work is based on Vilém Flusser’s text “On Memory,” in which he describes, among other things, the development of memory from prebiotic chemical evolution to the invention of electronic data storage.

“If memory is defined simply as information storage, then we find memories all over nature. They float like islands within the general stream towards entropy, islands that preserve information for a time before they dissolve. (…) The Second Principle of Thermodynamics (…) states that information contained in nature tends to be forgotten.” – Flusser: On Memory (Electronic or Otherwise), 1990

Accordingly, all stored information must, at some point in the universe, flow back into the general stream towards entropy. I find this idea absolutely fascinating since, regarded in this way, the concept of memory can also be applied to, for instance, DNA. This, in turn, establishes a connection to the emergence of life, such as, for example, the concept of the hypercycle that describes the transition from chemical to biological evolution.

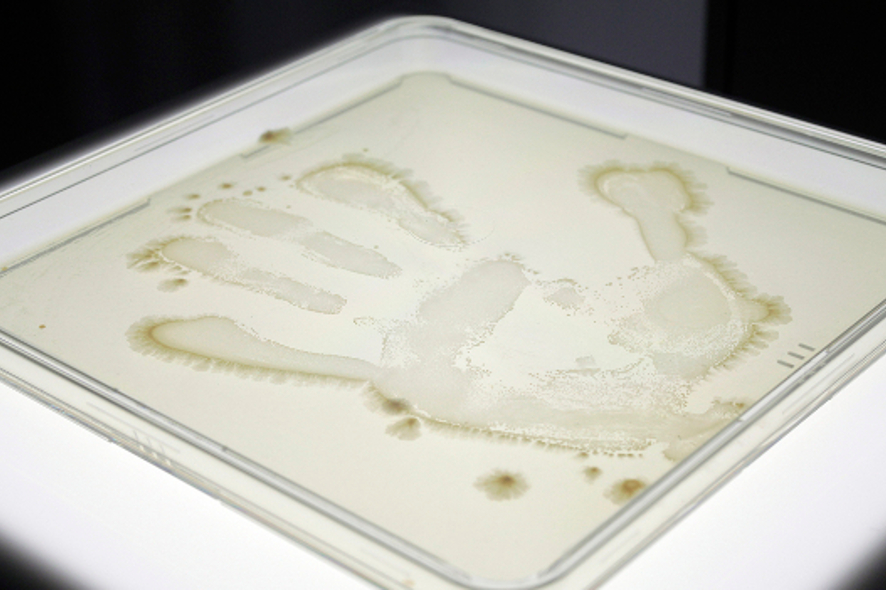

The microorganisms growing in the culture medium are traces that I left behind there—thus, a sort of visualized signature. And this is my way of raising some questions. What information do we leave in our wake—for instance, in a simple handprint? And, in turn, what conclusions can be derived from this information? Another one of my objectives in designing this installation was to visualize the circulation of information as postulated by Flusser.

The more these microorganisms proliferate and mutate, the more drastically the text is modified. What’s the significance of this “degradation” of the text?

Simon Krenn: The microorganisms grow in cell culture dishes at room temperature on a thin layer of agar medium, and a camera documents the progression of the various growth patterns. The bacteria introduced into the Petri dishes begin to undergo cell division and, finally, so-called colony-forming units take shape. Depending on various growth-determining parameters such as pH-value, nutrients and temperature, these colonies begin to propagate more or less, and, in doing so, change the original shape of the handprint. The more these forms diverge from the initial state, the more random mutations are integrated into the text that’s output by the typewriter. The disintegration of the text is thus based on, for one thing, the disappearance of my own handprint and, for another, the proliferation and self-replication of the biomass. Incidentally, the text is a scientific article on evolutionary biology.

Why do the colonies of microorganisms grow in the form of handprints? Does this have a special meaning?

Simon Krenn: The handprints are allusions to our interaction with keyboards, input fields, etc. Wherever information is produced, archived or stored, we usually find this form of alphabetical information processing which is based on a code that converts the sounds of the spoken language into visual signs. The typewriter isn’t operated by hand but rather by a handprint, so to speak, which is to say by living creatures that are outgrowths of this handprint.

Why did you decide to use a typewriter and not, say, a computer?

Simon Krenn: In principle, I certainly could replace the typewriter with a computer, since both are tools used to archive and preserve information. But ultimately, the mechanical typewriter appealed to me a bit more in this conceptual context, in that gradual, almost invisible changes in the Petri dishes are being translated into lots of mechanical actions.

How are the microorganisms linked to the typewriter? How does this work function on a technically level?

Simon Krenn: The typewriter is connected via an Arduino microcontroller to the two Petri dishes. The manually inoculated culture media, following an approximately three-day incubation period in a heat chamber, exhibit extensive growth of various microorganisms. The resulting bacterial and fungal cultures are captured by a camera affixed beneath the lid and the images are processed in real time. The individual growth morphologies of the colonies thereby engender the algorithmic recombination of the source texts. The way this works is that each processed letter is converted into a number that is, in turn, assigned to an electromagnet beneath the typewriter, which is what triggers the particular key on the keyboard. The outcome is a visual text composition that results from an endless recombination and reconfiguration of the individual text fragments.

TIME OUT .06 opens on Wednesday, June 8th at 6:30 PM in the Ars Electronica Center Linz: https://ars.electronica.art/center/eroeffnung-time-out-06/