Anyone getting off a train at Central Station in Chemnitz these days can’t fail to notice the shadow figures and gestures beckoning on the building’s LED-illuminated façade. They point the way to the Saxon Museum of Industry about three kilometers away, where visitors can enjoy a hands-on experience of forming digital shadows on their own. This show, which runs until March 4, 2018 and is entitled “Gestures – in the past, present, and future“, offers an opportunity to find out more about the subject of gestures , the research now being done in this field, and the various applications in which gestures will be employed in the future. From operating old looms all the way to Industry 4.0 and communication with self-driving cars—gestures will be playing a major role. They’re complex, and their significance has either undergone transition or remained unchanged for generations. Marianne Eisl is a project director at the Ars Electronica Futurelab and, together with Christopher Lindinger, that facility’s director of research & innovation, responsible for the substantive conception of the exhibition. In this interview, she tells more us about “manual language” and discusses a few of the 16 installations.

Why did the Ars Electronica Futurelab get involved with gestures in the first place?

Marianne Eisl: The Ars Electronica Futurelab in Linz confronts issues of great future importance on an ongoing basis. Accordingly, we’ve been working together with several major corporations on gesture control of autonomous vehicles since 2013. And anyone who has dealt with this topic from a scientific perspective as we do will have quickly recognized that gestures aren’t simple hand motions; rather, they have to be approached comprehensively, in a way that covers many different aspects. There’s even a scholarly discipline devoted to research on gestures and the effort to decipher and categorize them, to integrate the pertinent contextual factors into the consideration, and to analyze them in terms of linguistics.

And this is how we came to team up with Prof. Dr. Ellen Fricke, a gesture researcher at the Technical University of Chemnitz. She heads the German research project MANUACT, which investigates the interplay of hands, things and gestures in the workplace and in everyday life. And when we consider the direction of future development, we see that human beings will increasingly be working together with robots, so that gestures are sure to be a key element of human-machine communication in the near future.

So that’s how the Futurelab became a research partner of TU Chemnitz.

Marianne Eisl: Exactly. For Prof. Fricke, it was important to intensify our collaboration in gesture research with TU Chemnitz. An essential aspect of this research project is not only to discuss this topic on a scientific level, but also to conceive a public exhibition, to have input into its dramaturgy, and to contribute interactive installations. Especially here, of course, it’s important to bring in a scientific-technical perspective as well as an artistic one. That’s why we’ve also invited artists to contribute their takes on the subject of gesture research & control.

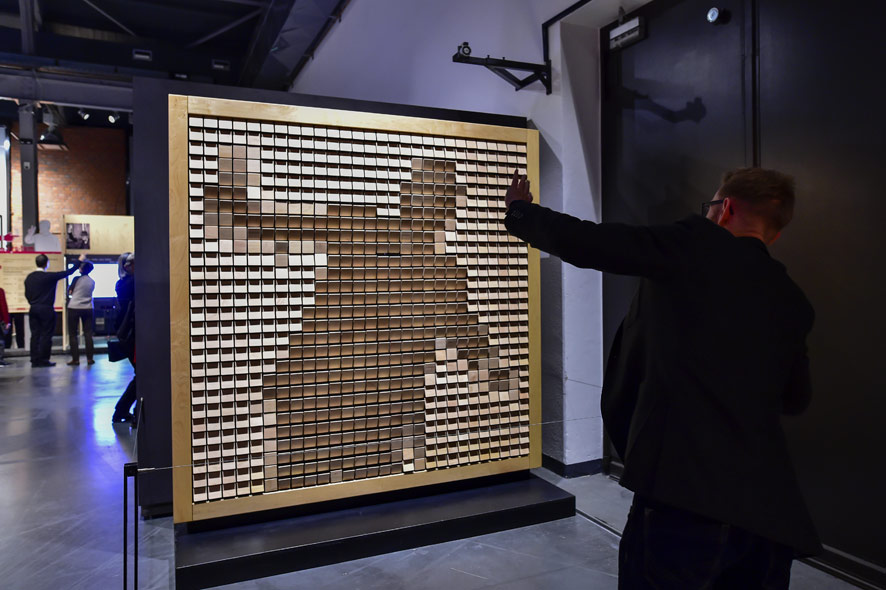

Wooden Mirror by Daniel Rozin. Credit: Industriemuseum Chemnitz / Sven Gleisberg

Which artists are involved in the “Gestures” exhibition in Chemnitz?

Marianne Eisl: The first thing you see upon entering the exhibition is an impressive work by Daniel Rozin that fascinated many of those who attended the opening. “Wooden Mirror” registers visitors’ movements on 800+ flexible wooden plates and translates them into pixel graphics. Golan Levin’s “Augmented Hand Series” features a video monitor on which images of visitors’ hands are deformed into odd constructs that provide ample food for thought. Certain gestures are represented by Jennifer Crupi’s metallic forms; wearers of them automatically assume poses that are familiar from everyday life. Visitors to Anette Rose’s “Captured Motion” enter a cube inside which previously recorded motion-capture data of people explaining things with their hands are displayed. Spectators see very graphically the traces of the speakers’ hands and the interaction of words and gestures.

The Futurelab also developed its own installations for this exhibition …

Marianne Eisl: The basic idea of this exhibition was to offer the general public a fun encounter with the subject of gesture research. The parameterization of gesture research, the various classes of gestures, the so-called gesture space—all of this is absolutely fascinating but, perhaps, not all that easy to get across. A playful approach, interesting technologies—our forte at the Ars Electronica Futurelab—and trying out different techniques for registering gestures were the main ways we went about tackling the assignment of conceiving this exhibition.

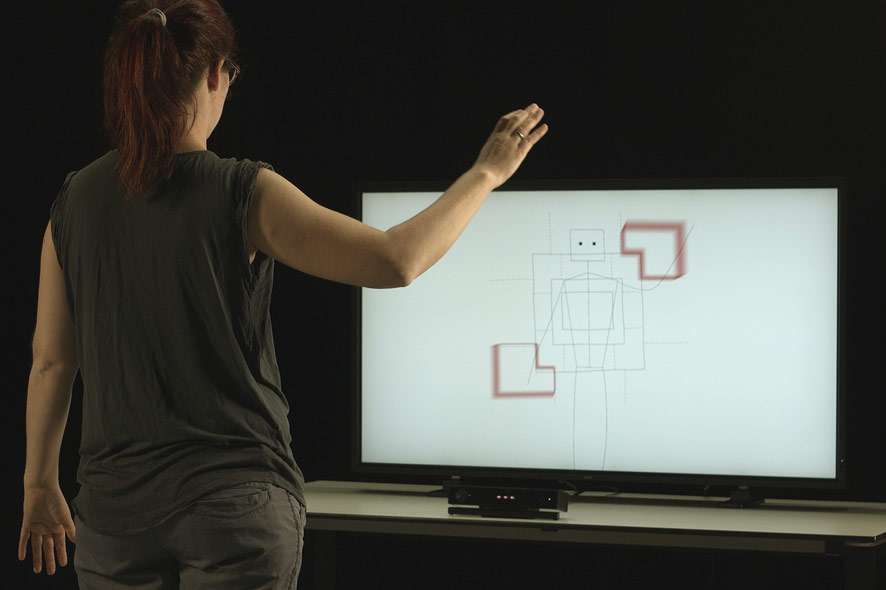

Gesture Space Visualizer, Credit: Ars Electronica Futurelab / Michael Mayr

The point of departure of every interactive installation we developed is a particular gesture that most people are familiar with—in order to then add a surprising element that triggers a shift in perspective. For instance, there’s the victory gesture in which you stick out your index and middle fingers to form the letter V. This gesture helped us to explain the term “gesture space” that’s so very important in gesture research. Consider this in light of the fact that the human body is divided into various sectors. When you position your hand making the victory sign next to your body, then a different meaning is ascribed to this gesture than when the hand making this V is positioned behind your own head—and thus in a different sector of the gesture space. The gesture suddenly takes on an entirely different meaning; in this case, many people don’t interpret this as a sign of victory but rather as rabbit ears. And visitors to this interactive installation can try this out for themselves. Here, we show which particular sector of the gesture space each gesture you make yourself is positioned in.

Virtual potter’s wheel, developed by Ars Electronica Futurelab. Credit: Industriemuseum Chemnitz / Sven Gleisberg

Will we use different gestures in the future than we use today?

Marianne Eisl: The question of the spectrum of significance comes into play with every gesture. The meaning of gestures changes repeatedly over the centuries, and one of the reasons for this is that technologies change—and that will continue to be the case. In the exhibition, we’ve included various historical exhibits that demonstrate precisely this process of change. Thus, with the demise of the telephone receiver and the proliferation of the mobile phone, the gesture for telephoning has changed. Nevertheless, numerous gestures having to do with old-fashioned devices—making pottery, for example—are still intuitively rooted in our imaginations and can thus be reassigned for use in future interfaces. Thus, we have a “virtual potter’s wheel”, an installation in which visitors use their hands to shape virtual vases and other objects, and this got a very enthusiastic reception from people at the opening in the Saxon Museum of Industry. They apparently haven’t forgotten this gesture.

A ball labyrinth controlled by gestures. Credit: Industriemuseum Chemnitz / Sven Gleisberg

How familiar are exhibition visitors with control via gestures?

Marianne Eisl: For most people, controlling objects via gestures is simple and intuitive. At TU Chemnitz, that was one of the research topics, and we’ve dedicated an installation to it in the exhibition. Here, visitors can fly virtually over a globe, and installation visitors quickly discover how this works with the appropriate airplane gesture. But existing hand signals can also quickly be replaced by other intuitive gestures. This is demonstrated by our ball labyrinth, a game of dexterity that entails manipulation on two axes. Our game is operated by gesture control, so all the player has to do is tip his/her palm to impart that movement to the playing surface. Installation visitors quickly figure this out and have a lot of fun in the process.

Marianne Eisl has been a senior researcher at the Ars Electronica Futurelab in Linz since 2015. While working in Vienna as a developer of applications for use by law & notary firms, she studied media informatics at the Technical University of Vienna and gained experience as a tutor in conjunction with undergraduate courses: Algorithms and Data Structures, Video Analysis, and Video Analysis of Human Motion. For her master’s thesis, she dealt with microcontroller programming, sensors and intuitive interface design, and, following graduation, continued to work in this area at TU Vienna.