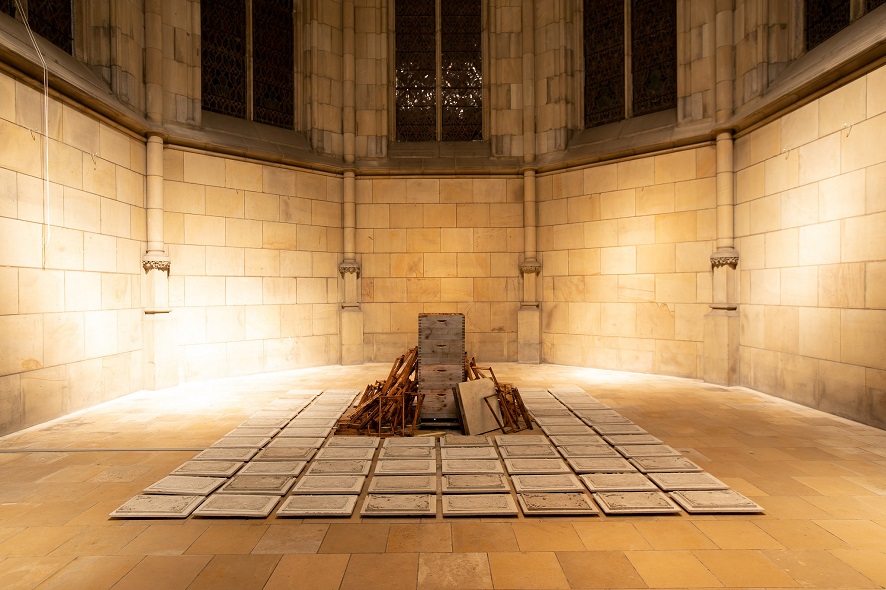

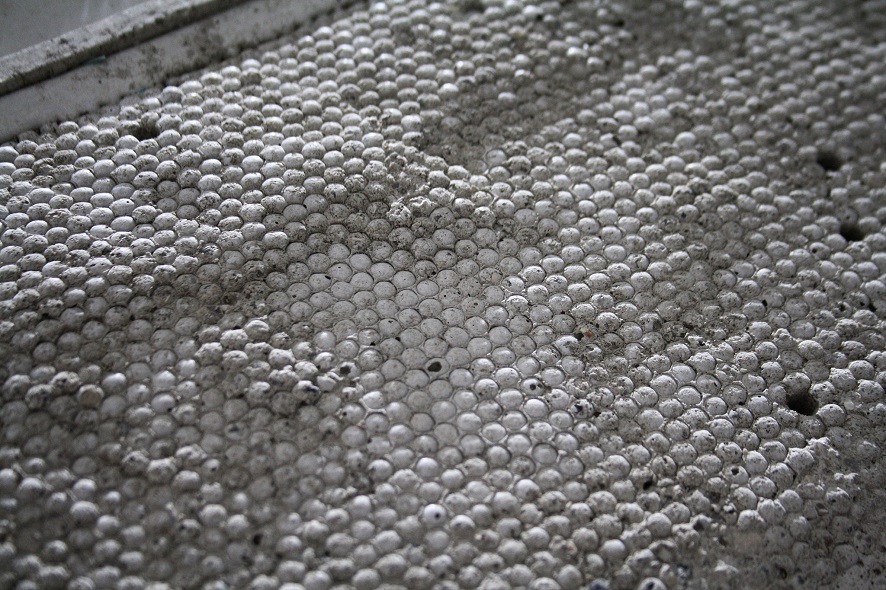

Concrete plates manifest impressions of honeycombs, distorted sounds are emitted by loudspeakers, the work’s surface is oddly soft—almost like wax. “The Bien” by Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer deals in artistic and aesthetic terms with the die-off of an entire colony on bees. Mourning and frustration over the honeybees’ absence segued into months of casting work to produce a piece of art that portrays the bee colony strictly in terms of its absence.

We met with Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer in his atelier near Linz and observed him at work. In this interview, he tells us more about “The Bien,” which will be on exhibit in Linz’s Mariendom cathedral during the Ars Electronica Festival September 6-10, 2018.

Stefan, how did “The Bien” come to be?

Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer: Dealing with this was an offshoot of my artistic research into honeybees that was triggered by the bees’ absence due to colony collapse disorder, which wiped out this population. Bees have an ingrained behavior whereby sick individuals leave the colony. On account of my grief and frustration about the bee colony’s sudden absence, I became curious about what happens when the empty beehive is simply left for nature to take its course. Who moves in? What does that look like? I learned that many other creatures take over these premises: for instance, ants, hornets and hedgehogs, not to mention wax moths. At the end of the clean-up process, all that’s left is wax, which served as the raw material for my artistic work.

It’s what you might call a spinoff of my artistic research with honeybees that wax became available to me as a material I could work with and subject to a subsequent transformation process. This is, in general, very important in my work as an artist—taking something and changing it, transfiguring it, processing it, and then creating and designing something new out of it.

“The Bien” is ultimately an attempt to manifest an idea in this transformation process in the form of concrete and thus to render a portrait of the bee colony. The name “The Bien” is an antiquated designation for a bee colony. To the concrete plates, I added sound, noise inspired by the acoustic experience you have when you work with bees. A beekeeper encounters a lot of different sounds, and reaches diagnoses as to the bees’ condition on the basis of sounds—whether they’re excited, in a good mood, or meek and mild. I made an effort to transform this into sound. Transformation plays a major role here as well, in that I take a preexisting object, and attempt to divide it, cut it up and form something new out of it.

Credit: Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer

You start with a very pliable material, wax, and then work with concrete. Why?

Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer: Concrete is always as smooth as the form. I find that conserving such an ephemeral material as wax in concrete is a very fascinating challenge or approach. And there’s a reflection of this—you see the surface of the wax in the concrete, and you feel it too. It’s interesting to conserve it in this form and, so to speak, preserve the current state of the wax.

How did your fascination with honeybees begin?

Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer: It’s a personal interest of mine. I’ve been around bees since I was a kid when my father kept bees. So beekeeping has long fascinated me, and then a few years ago I decided to make this the subject of my artistic research. I wanted to know what I could learn from working with bees. What effect would this have on my artistic production? What could we as an artists’ collective learn from this about modes of production? What does this mean aesthetically?

Credit: Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer

When a population is wiped out by colony collapse disorder, does it mean that an error was made?

Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer: When a colony dies off, of course, you’re confronted with this issue. A beekeeper always has to face the question of what or who is to blame—even though one of the basic principles of the training is that shame and guilt are irrelevant to beekeeping! There are many, many factors in beekeeping practice that you can’t influence. Nevertheless, mistakes might have been made. We introduced the Varroa mite because we wanted to see how the European bees coped with this. Plus, we bred Carnica, a bee species that is very docile and industrious, but its resistance to disease and ability to defend itself against enemies is low. So, naturally, you start to consider the extent to which it’s a mistake to intervene and make it easy for ourselves. It’s a question of capitalism and exploitation, but there are also personal questions. Did I do all I could? Did I treat them against Varroa mite in a timely manner and with the right methods? Were my observations right; was the colony too small; were the feed supplies adequate? It’s difficult to know where to stop this. There are a lot of good, experienced beekeepers who lose 80% of their bees in the winter. So there are no hard-and-fast rules that this conforms to. What I can say for myself is that you definitely feel terrible, whereby this is also a moral assessment. I nevertheless decided to go forward with a positive attitude and to say: Next time, I’ll do it better.

Credit: Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer

When you talk about bees dying off, thoughts immediately turn to errors and the question of how we’re treating our environment as a whole.

Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer: Exactly. This really is a matter of the industrial approach to nature, and thus the question of how to make a profit as large as possible as quickly as possible. This is ultimately reflected in agriculture overall and is ultimately manifested in the dying off of bees. This brings us to pesticides like neonicotinoids that are used to “protect” crops but at the same time cause damage to organisms. Grief is ever-present in the subject of how humankind deals with this.

What do you see as a strategy for dealing with this human failure?

Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer: Learning is the only way, learning in the sense of admitting mistakes were made and seeing to how we can make up for them. This might be somewhat starry-eyed or naïve, but the bottom line is that I believe in this.

It’s an interesting approach that you’ve set this mistake in concrete, so to speak …

Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer: It’s important to me not to do finger-pointing. It’s an effort to consider the absence of something in neutral terms. When you see these images and the concrete slab, there’s something dystopian about it. What I mostly associate with it, though, is the aesthetics, the formal design aspects. It’s as if I were drawing a landscape, and I sketch the background but leave out the tree that’s right in the front center. In other words, I’m portraying something in terms of its absence. It’s a similar approach here. With concrete images, with the empty beehive and with deconstructed sounds that are meant to contribute to the mood, I’m attempting to record something. Ultimately, it’s an effort to hold on to a moment.

Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer is a lead producer and artist at the Ars Electronica Futurelab. He studied visual arts and cultural studies in Linz Art University’s Painting and Graphics program, and has been a PhD candidate under the tutelage of Prof. Karin Bruns and Prof. Thomas Macho since 2012. He has worked at the Ars Electronica Futurelab since 2001, and has been a member of the MAERZ artists’ association since 2006.

The Bien, a work by Stefan Mittlböck-Jungwirth-Fohringer can be seen at the Ars Electronica Festival September 6-10, 2018 in Mariendom [St. Mary’s Cathedral]. For details, go to our program website.

To learn more about Ars Electronica, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter, and check us out online at https://ars.electronica.art/news/en/.