Artificial intelligence as construction site manager? Networked components equipped with sensors that constantly relay information about their location and current state? Self-driving robots or industrial assembly right on site? The possible future scenarios for the construction industry are as diverse as they are amazing! How construction companies can position themselves amidst all these technological developments was the subject of “Digital Innovations in the Construction Industry,” an Innovation Lab staged in April 2018 by the WKOÖ–Upper Austrian Economic Chamber and the Ars Electronica Futurelab for firms involved in the construction industry.

We met with Maria Pfeifer, senior curator and researcher at the Ars Electronica Futurelab, to learn what an Innovation Lab actually is, what uncertainties are emerging on the construction industry’s horizon, and what futuristic construction projects are already in progress.

Credit: Nicolas Naveau / Ars Electronica

The Ars Electronica Futurelab hosted this Innovation Lab in cooperation with the WKOÖ. Tell us about the program?

Maria Pfeifer: An Innovation Lab is a format that we actually use for employees of big companies working on product development. It’s a setting in which to explore approaches to ideas on the way to prototyping. For our collaboration the WKOÖ, we adapted the format to work with employees from several different companies in a single industry—in this case, construction. For one thing, this is a matter of taking a critical look at certain future developments and seeing what impacts they’ll have on various sectors. Here, companies can assess for themselves where they can and will position themselves amidst these technological shifts. How will the company go along with digitization processes and at what point do you make an informed decision to bail out? In other words, an Innovation Lab is a presentation of potential future scenarios from which concrete ideas can be developed and, thus, innovation potential that exists today can be identified. We can’t know exactly what will be coming at us in the future, but that’s not what we’re claiming to do here. We want to consider what-if projections and derive inspiration from projects that are well-adapted to future developments. We describe future scenarios and draw conclusions about how to act in the present.

Credit: Peter Freudling

How do you set up the program of an Innovation Lab?

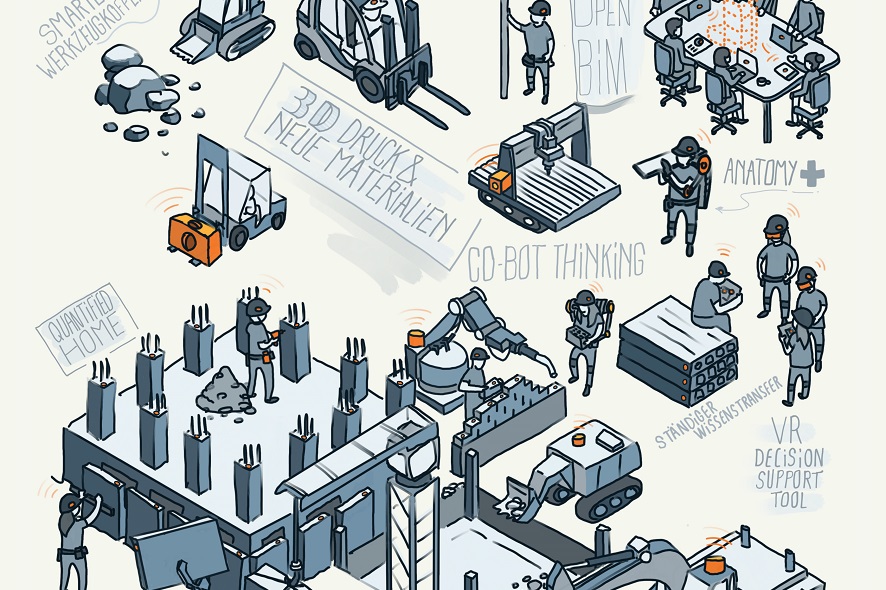

Maria Pfeifer: In the case of this Innovation Lab on digital innovations in the construction industry, WKOÖ members in this sector—for example, architects and manufacturers of building materials—made suggestions. We began with Video Seeding—each participant received a video containing film snippets of projects related to the topic, which the participant could work on in advance. Here, it’s important to establish a topic with a tight focus, and we focused on installation robots on the construction site, 3-D printing and new materials, drones and measuring technology, logistics and enhanced assistance functions. We wanted the topics to be relevant for small & medium-size firms too. Among the film snippets were examples of start-ups including those in the artistic field, which heightened curiosity about the topic. Following the introductory video, I conducted individual interviews with all the participants to get reactions and find out about specific interests.

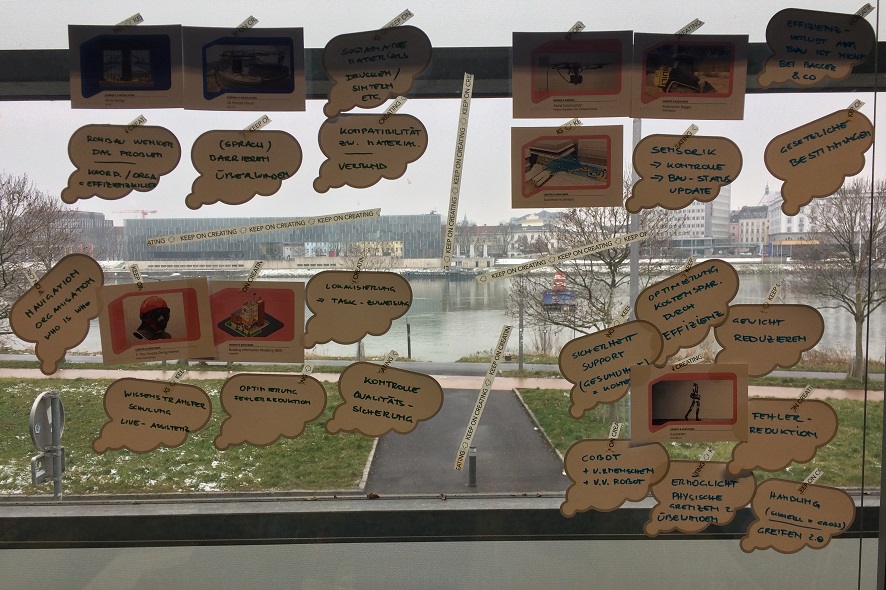

On the day of the Innovation Lab itself, we work with Seed Cards about interesting, catchy projects, which don’t necessarily have to have something to do with the construction industry; instead, inherent in it has to be a strategy that can be crystallized and applied in another field. Of course, there are examples like a self-driving earthmover, but there are also rather more eccentric projects like “Solar Sinter” by Markus Kayser, who uses a framework he built himself to take advantage of solar energy to do additive manufacturing in the desert. Another example is the bridge built by MX3D, whose basic idea is on-site construction. Now, we’re not saying that everybody should get started using industrial robots to build a bridge; instead, this is a matter of the strategy of shifting production to where the product will be installed. The projects on the Seed Cards are sources of inspiration to make it easier to visualize the issue under discussion.

How do you bring together topics for such a diverse group so they’re relevant to everyone?

Maria Pfeifer: It was really a very interdisciplinary group and not just the staff of an individual firm. We work with a method we call Future Placement, whereby the starting point is the world as it is now, and you proceed to examine how things will change when you bring to bear one of the strategies with great future promise. We started off by examining the participants’ concepts and their work. They had 10 minutes to draw a picture of their workplace or a part of their work process. In this way, we can build upon the workplace reality of an individual person. We then investigated this process in terms of changes. In groups using Seed Cards, there was a discussion of what the person finds interesting, what s/he could imagine, what ideas they themselves had, how they could be implemented, and where the problems might crop up. They presented the results to one another, and this led to the crystallization of a few points that we took up again in our Report. One example is mass manufacturing of products that are simultaneously individualized, an approach that we’re already familiar with and one that will certainly progress further in the future. Or what it would be like if a construction site were managed by an assistance system that already knows where things are, where everything is interconnected? What would it be like to work in an environment in which every component had a sensor? In which the push of a button is all it would take to print out a status report or an expert assessment of a particular building?

Inspiration for innovations in construction: AIRSKIN by Blue Danube Robotics.

What topics were especially relevant for these companies?

Maria Pfeifer: The two most interesting topics for these companies were decision-making aids—both with virtual reality and with artificial intelligence—and the prefabrication and standardization of building components. With digital decision-making support, clients could, for example, get a better idea of what the building will finally look like, what impacts economic and ecological factors would have, what they’ll cost amortized over the useful life of the structure, and how the design will look in concrete terms. As for prefabrication and standardization of building components, the companies see lots of innovation potential in doing more prefabrication without everyone necessarily ending up with the same house. In fact, when considering the possibilities of digital manufacturing, you always have to keep in mind this type of prefabrication in which components can be customized—which would otherwise have to be done by hand and thus cost a fortune, or even be impossible to do.

What reservations do these companies have?

Maria Pfeifer: Does it pay for me to do this? Is it worth the effort to train someone or to get started with building information modeling (BIM)? Another area of concern is the issue of open access: Is certain software available only by acquiring a license? And are a company’s data deleted as soon as the license expires? There are also concerns about whether everyone has to use the same system—for instance, if the architect uses BIM and the window vendor does too but the installation firm doesn’t, then all the work was for nothing. The effort up front would simply be too high.

Why would everyone have to participate in the case of BIM? How does the system work?

Maria Pfeifer: BIM displays a digital real-time model of the building, which automatically changes when someone enters new data. So then, you don’t have to send blueprints back and forth, and when you make changes, you can immediately see the implications. If you make one door smaller, then the system automatically recalculates the number of bricks you need. Now, in theory, you would think: Wow, this must be great! But if people have to update the data themselves and every change has to be painstakingly input into the system, then it won’t work. But in a vision of the future in which that is done by sensors, it could work. At present, we’re in a transitional phase with this.

What role does the Ars Electronica Futurelab play at an Innovation Lab?

Maria Pfeifer: Our goal is for Innovation Labs to give rise to R&D projects that can be implemented with us or other partners in the region. In this case, we’ve been fortunate enough that this has already happened in the form of a concrete project, though I don’t want to reveal any more at this time. We regard our role in this context as being an enabler—that is, above all, we want to show traditional sectors and smaller firms that their rightful place is in the middle of this, and that they should have their say and have some input into these digital developments. Even small & mid-size companies in Austria can get involved in trailblazing projects and consider how they want to be working on the construction site of the future.

Maria Pfeifer is a senior curator and researcher at the Ars Electronica Futurelab. Her work focuses on the future of design, innovation inspired by art, and collaboration between art and science. She also manages the Futurelab’s Artist-in-Residence program. She studied art, comparative literature and cultural studies in Vienna, and wrote her master’s thesis in 2013 on visualization of literature. She divided her time between the Ars Electronica Festival and the Futurelab from 2011 to 2016; since then, she has worked exclusively at the Futurelab.

To learn more about Ars Electronica, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter, and check us out online at https://ars.electronica.art/news/en/.