Since March 13, the Ars Electronica Center has been officially closed due to the Corona crisis. Where young and old visitors alike usually gather to talk with our infotrainers about the impact of new technologies on our lives, it’s unusually quiet at the moment. Yet it is not completely deserted, in the Museum of the Future in Linz. One person who can be found here frequently these days is our colleague Thomas Schwarz, for example. We stopped by the Ars Electronica Center and asked him – while observing the currently required safety distance – what he’s so busy with these days.

We start our tour at the very beginning, in the foyer, where there is a lot of activity during regular museum operations, where visitors can buy their tickets, get information about the various offers and programme items on large screens or wait for admission to the next Deep Space 8K presentation.

Our path then leads us straight to the 1,000 square meter Main Gallery, which houses the “Understanding AI” exhibition, the „Global Shift“„Neuro-Bionik“ und das Machine Learning Studio.

It’s not only quieter than usual here, but also a little darker, because screens don’t light up at all corners and ends. But suddenly the lights go on…

…and Thomas Schwarz shows up. He’s been working at the Ars Electronica Center since 2015, initially as an infotrainer. “I’ve been working in the museum technology departement for about a year now, and since then I’ve also taken over responsibility for the new Machine Learning Studio, a very versatile job.” Today he is busy repairing “SEER”, the popular robot that mimics the emotional expression of the viewer. After that, the maintenance of the artwork “ObOrO” is on the agenda. Finally, he’ll tell us how the Ars Electronica Center’s FabLab is making a small contribution to the fight against the corona virus. But see for yourself:

What are you working on right now, on “Oboro”?

Thomas Schwarz: The towers can be moved very easily via cable pulls so that they can sway back and forth. But the cable pulls, which are equipped with fishing lines, tear again and again and have to be reattached to the motors. The LED diodes have also been reset correctly so that the system can switch on automatically in the morning. We now have more time to deal with mechanical problems, whereas we usually deal with software problems during regular museum operations, and it’s only on mondays when the museum is closed that we have time to fix the hardware problems”.

What does it actually feel like to work in an almost deserted Ars Electronica Center?

Thomas Schwarz: For me, the Ars Electronica Center is a wonderful place where I simply enjoy spending time. Because no visitors are allowed to come here at the moment, there is clearly more time for us to work on certain projects and improvements. Otherwise, this is only possible on Mondays when the museum is closed. It is now easier to deal with some things in more detail in peace and quiet. On the other hand, I really miss the exchange with the colleagues, the visitors from all over the world, the hustle and bustle that normally prevails here and the diverse everyday work in General.

“It is easier now to deal with some things in more detail in peace and quiet. On the other hand, I really miss the exchange with colleagues, visitors from all over the world, the hustle and bustle that normally prevails here and the diverse everyday working life in general.”

As a techtrainer you are also constantly in contact with the visitors. Not only can they watch you repairing various robots, but they can also ask you questions, Right?

Thomas Schwarz: It is often very exciting when visitors come to you with more detailed questions and you can show them what you are working on or what you are developing. It is always nice to see how inspired many visitors are by what we do here. And how easily we can often take away their fear of trying something from the AI field themselves.

What projects are you working on right now?

Thomas Schwarz: SEER, for example, he has a slightly drooping eyelid that we haven’t been able to fix yet. So I’m now in the process of taking a closer look at the basic problem so that I can present him better again in the future. The aim of my repair is to bring every little detail back to its original condition, to replace small servo motors, in total there are 12 of them. It is possible that they will burn out or break over time, they have to be removed and reinstalled, which is a big challenge with the hoists also installed in SEER. The artist was here for three days during the summer and worked on SEER to solve some minor problems, but also faced some difficulties himself. So we can’t always rely on instructions from the artists, but have to find ways to repair something and work on it ourselves.

What else do you do?

Thomas Schwarz: In the Machine Learning Studio we work on further developments. For example, we want to make the interfaces of the self-propelled cars a little simpler, i.e. more user friendly. But a lot is also done from home. There are currently only a few colleagues on site, working on their projects on different floors.

What do the techtrainers who currently work at home do?

Thomas Schwarz: One colleague has a Donkey Car from the Machine Learning Studio at home to teach it something very specific. It’s about more user-friendly interfaces for starting the car, adjusting the autopilot and improving the camera display in the exhibition. We want to make it possible that after training a car like this, you automatically get the video that is created, showing what is actually relevant to the self-propelled car, what is recognized, what helps the car to stay on track. It is often exciting to see that it is not only the lines on the race track that affect the behavior of the car, but what other factors such as screens or visitors’ shoes influence the car.

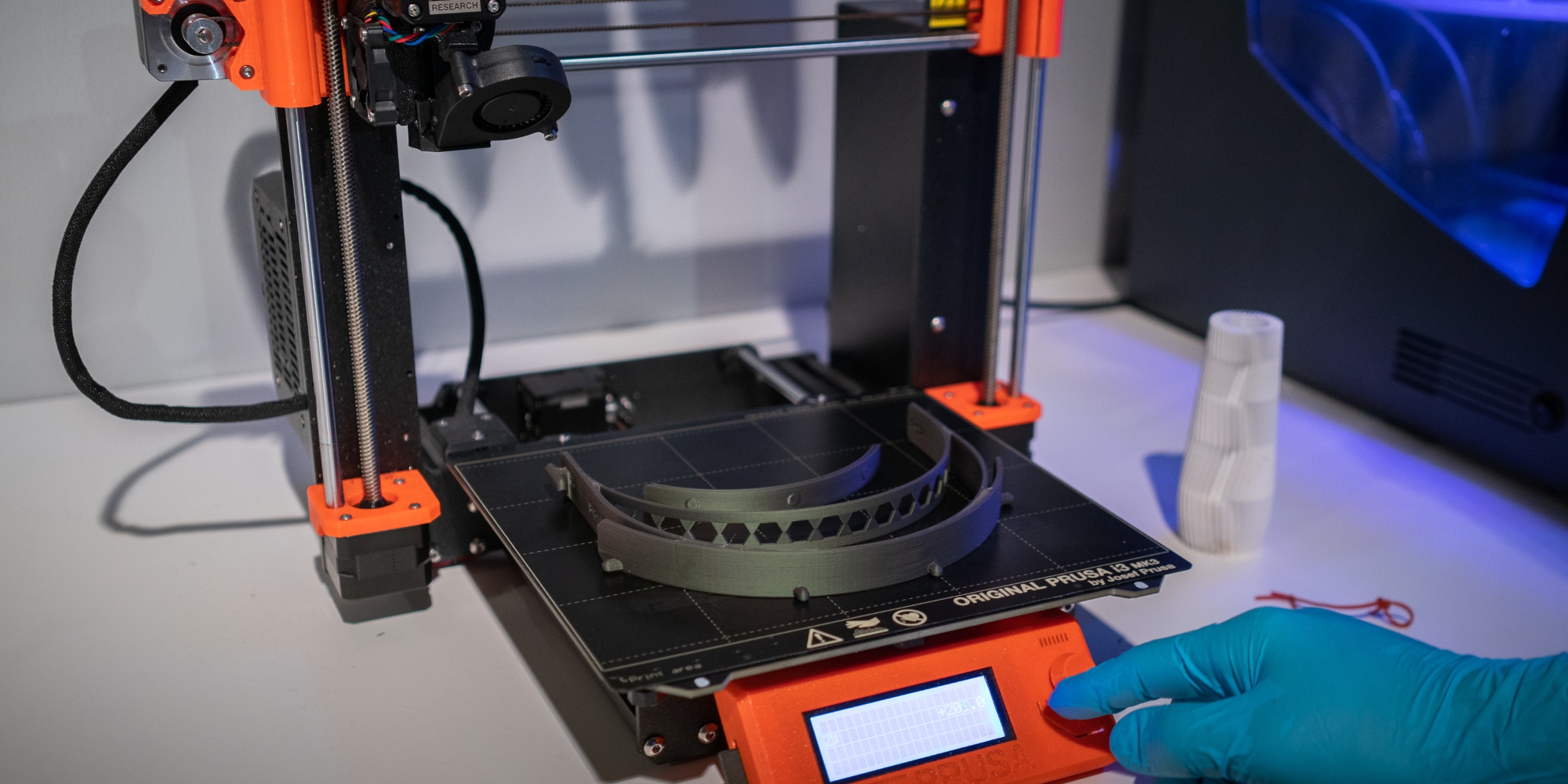

I’ve heard that you’re currently finishing face shields on the 3D printer – a good idea in the current situation. What do you need to get a finished face shield? What exactly does it consist of, what steps are necessary for the production?

Thomas Schwarz: The most important thing is of course the 3D printers, of which we have five copies available that are ready for use. For the face protection we use a laminating film here, which is cut by a laser cutter here, but it could also be cut with scissors. We print with PET-filament, which has good hygienic properties. The whole thing consists of a laminated sign, which is cut out by the laser printer, and a head holder, which is produced by the 3D printer. There are two different versions for the face shields, one slightly larger and one smaller. It should also be mentioned that this is the Protective Faceshield from the Prusa company, who came up with it. Our 3D printers also come from this Czech research company.

How did you find out about this development in the first place?

Thomas Schwarz: I myself have a 3D printer from this company at home and am therefore up to date on their developments and very soon I was looking for possibilities to use a 3D printer in our current situation. Prusa itself has a printer farm with 1,000 3D printers, which has now been converted to the production of such masks. The copies produced are already being used in the Czech Republic.

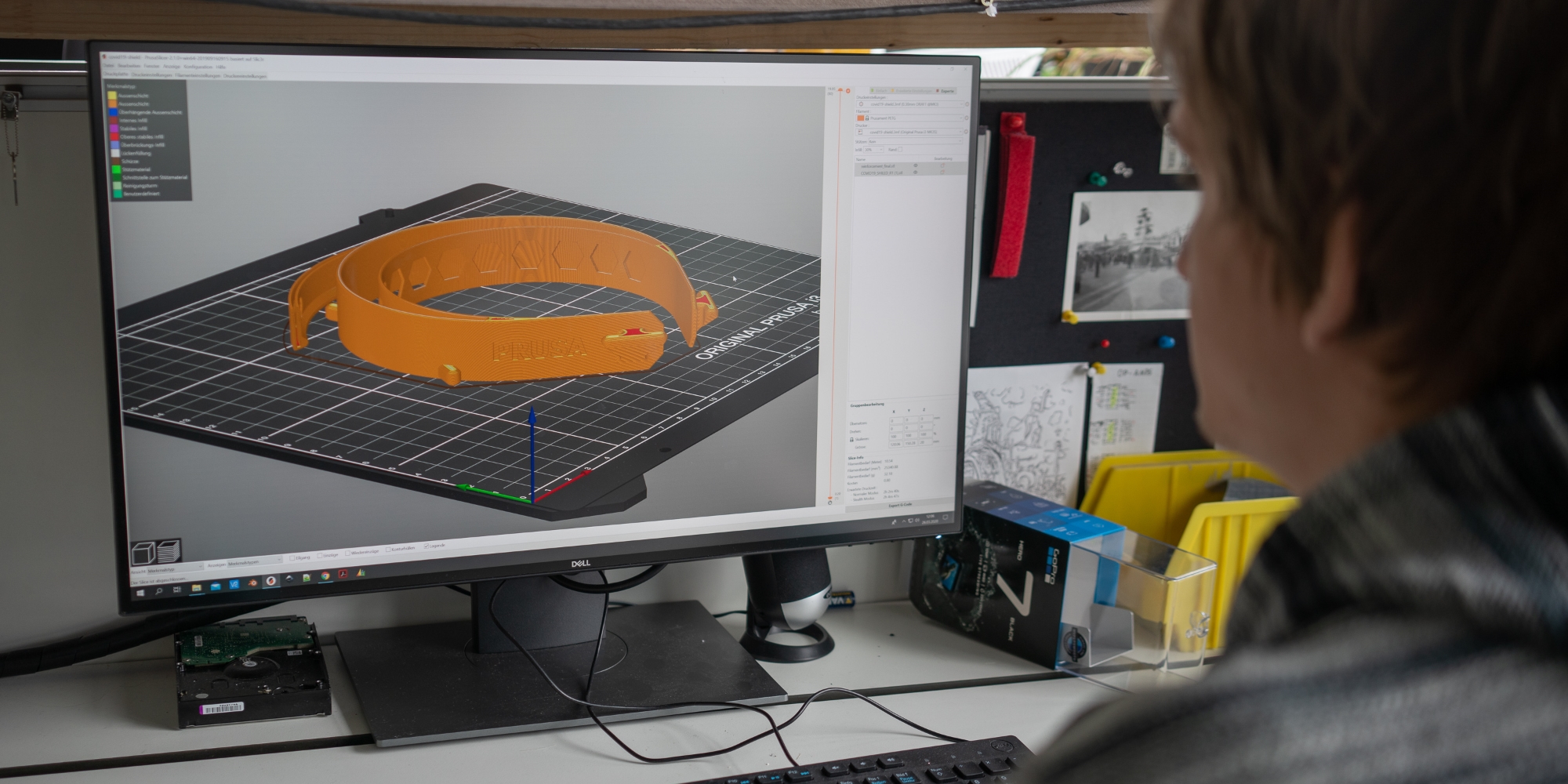

What exactly do we see here on this screen?

Thomas Schwarz: Here we have a so-called slicer program that converts a 3D model into the various layers for the printer. Here we can already see the model of a protective mask, which is then sent to the 3D printer. The 3D-print for the smaller copy comes, if you calculate the material costs, to a little more than 80 cents, the larger version to about 1,30 Euro. The printing process takes between two hours two minutes and two hours 50 minutes.

Thomas Schwarz has been working at the Ars Electronica Center since 2015; for the first four years he worked as an infotrainer. He’s been working in the museum technology departement for about a year now and since then has also taken over responsibility for the Machine Learning Studio. He’s also currently writing his master’s thesis at the University of Art in Linz and is also active as a freelance filmmaker, cameraman and media artist.