[infobox]EMAP/EMARE – The European Media Art Platform is a European platform for digital media financed by Creative Europe. Its aim is to support artists working in this field, especially emerging European artists working critically and innovatively with (digital, but not only) technologies. In 2020 Kasia Molga was selected for her residency with Ars Electronica. The results of all previous EMAP/EMARE residencies since 2018 will be shown at the Werkleitz Festival from June 17 to July 4, 2021 in Halle an der Saale, Germany.[/infobox]

Kasia Molga does not want to be placed in certain categories. She describes herself as a “design fusionist” and “series starter”, i.e. as someone who finds far too many things in this world interesting and is constantly discovering new topics for herself. In the fall of a year ago, the loss of several people close to her prompted her to take a closer look at the topic of mourning in her work as well. After the acceptance for a EMAP/EMARE residency the lockdown by COVID-19 in spring gave her the next impulse for the project “How to make an Ocean?” and revised her original plans.

In the interview, Kasia Molga presents the path to her project – from collecting her tears to a crying bot to help us all shed a few tears – and talks about the role of art, which she believes can best show connections rather than being purely didactic. But she also talks about the separation of the human and the non-human, and gives honest advice to emerging media artists.

What topics have become dear to your heart (and why)?

Kasia Molga: The main topic which is always present in my work is human and non-human makers’ relations, increasingly mediated through the layers of technology.

By “non-human makers” I mean other than human Earthlings – organisms, other animals, processes or organic forms of intelligence constituting the life on this planet, and by “relations” I mean the way we all are inherently and intrinsically interconnected, influencing the state of flux and thus the route of events happening within our biosphere – affecting all and everything in the end.

While the environmental theme has been always present in my work – or in fact my life – to keep examining this relationship which we have with so-called nature has been in my opinion one of the most urgent topics for at least three decades now. And so what I am passionate about in my practice is to critically look at the aforementioned increasing layers of technology in attempt to “human un-centre” it – so that I can amplify presence and voices of the non-human makers; while finding points of connections – so that we can consider nature as a partner and collaborator rather than a product. I often work with real time environmental data which I consider a record of these relations between us and non-humans.

Still from the artist’s journey, a film commissioned by Ars Electronica for the Ars Electronica Festival, Credit: Kasia Molga

Still from the artist’s journey, a film commissioned by Ars Electronica for the Ars Electronica Festival, Credit: Kasia Molga

Which projects are you currently working on?

Kasia Molga: And so continuing from this introduction, there are few things I am working on at present: “By the Code of Soil” which is my EMAP / EMARE Ars Electronica residency project.

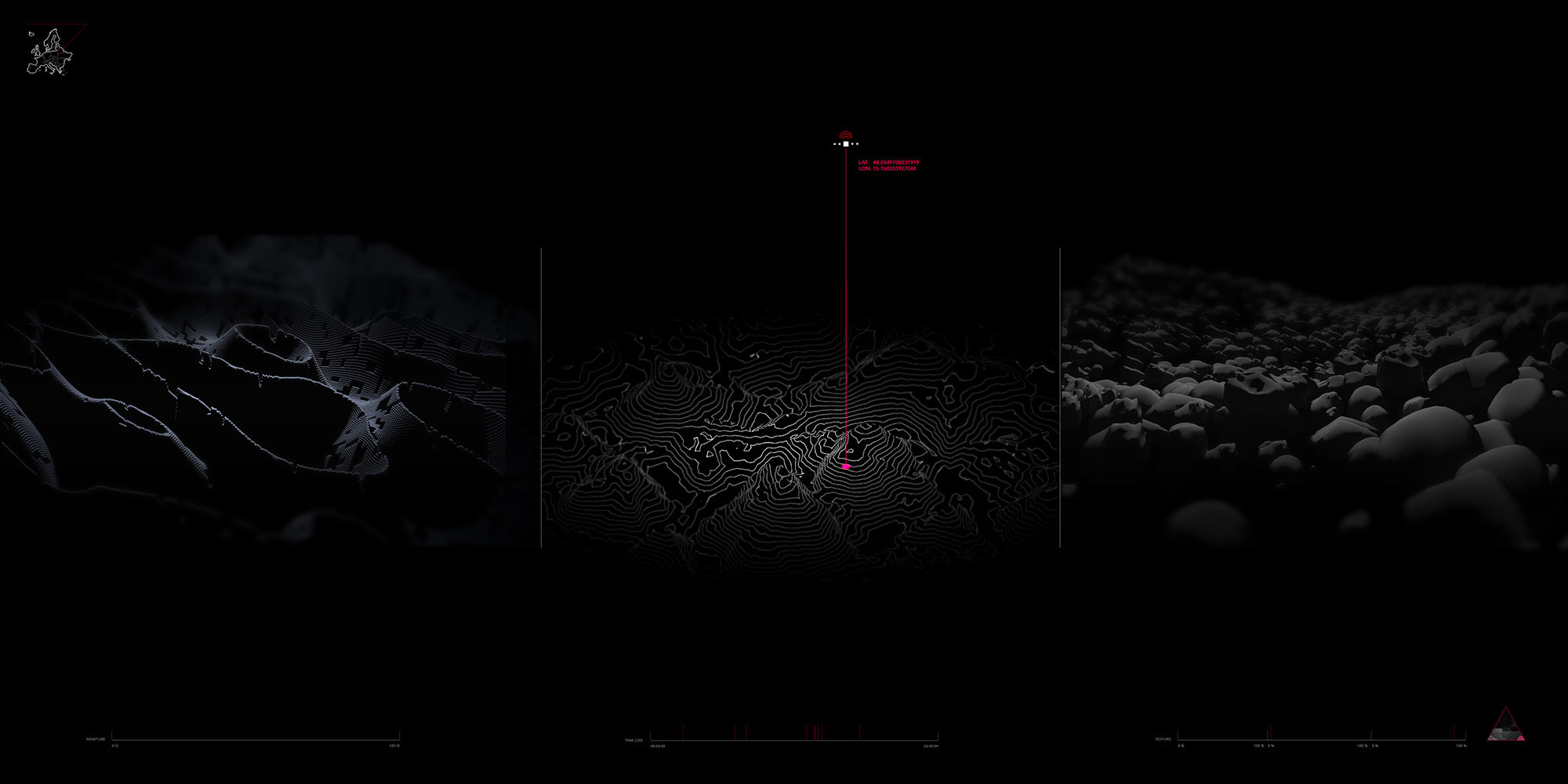

And in parallel together with my collaborator – a sound artist Robin Rimbaud aka Scanner, we keep working on various forms of By the Code of Soil – which initially was a computer virus released a little over a year ago – as a result of our collaboration with GROW Observatory and part of the STARS EU residency. It was a distributed artwork over the network, manifesting itself as a sort of audio/visual event which took over participants’ computers for around 2 minutes, whenever the satellite Sentinel 1A passed over. The sound and visuals were formed based on the data coming from some soil moisture sensors distributed by GROW Observatory across European soils. The project is finished now and the virus is not active any longer, but Robin and I worked on the “gallery” version of the project as well as a performance.

One of the things which I explored in this work was how can we re-connect or heal our connections with such basic, but vital, essential and life-affirming matters as soil – through the interface of the computer which is now an extremely prevalent way of experiencing the word.

Screenshot from one of the many manifestations of By the Code of Soil, Credits: Kasia Molga

Screenshot from one of the many manifestations of By the Code of Soil, Credits: Kasia Molga

And so continuing with that I started thinking about code, CGI, digital technologies, the way we use our computing devices, the data we produce and consume (among other things By the Code of Soil which was quite large to download and required quite some CPU to be able to exist on people’s computers), and started considering other, lighter in kb, forms of expressions and connections with the natural world through the interface / layer provided by our computers. I received a grant from the UK Arts Council to do research with the aim to expand my practice. I have been working on a sort of light in kilobytes – environmentally friendly, real time data driven audio visual event using a python, to be seen in people’s terminal windows. I started working on it a few months ago, but it really became relevant during the lockdown which on one hand further contributed to disconnection from the outside world. So many of us rely on networks to provide us with the “window” to the world in order to continue this “ill – perceived productivity” and overloading internet connection. So I started creating something light, fun, which hopefully will convey or encourage us to rethink our digital reality, the way we use it, the way we experience the physical natural reality and the way we notice and appreciate other than human forms of intelligence.

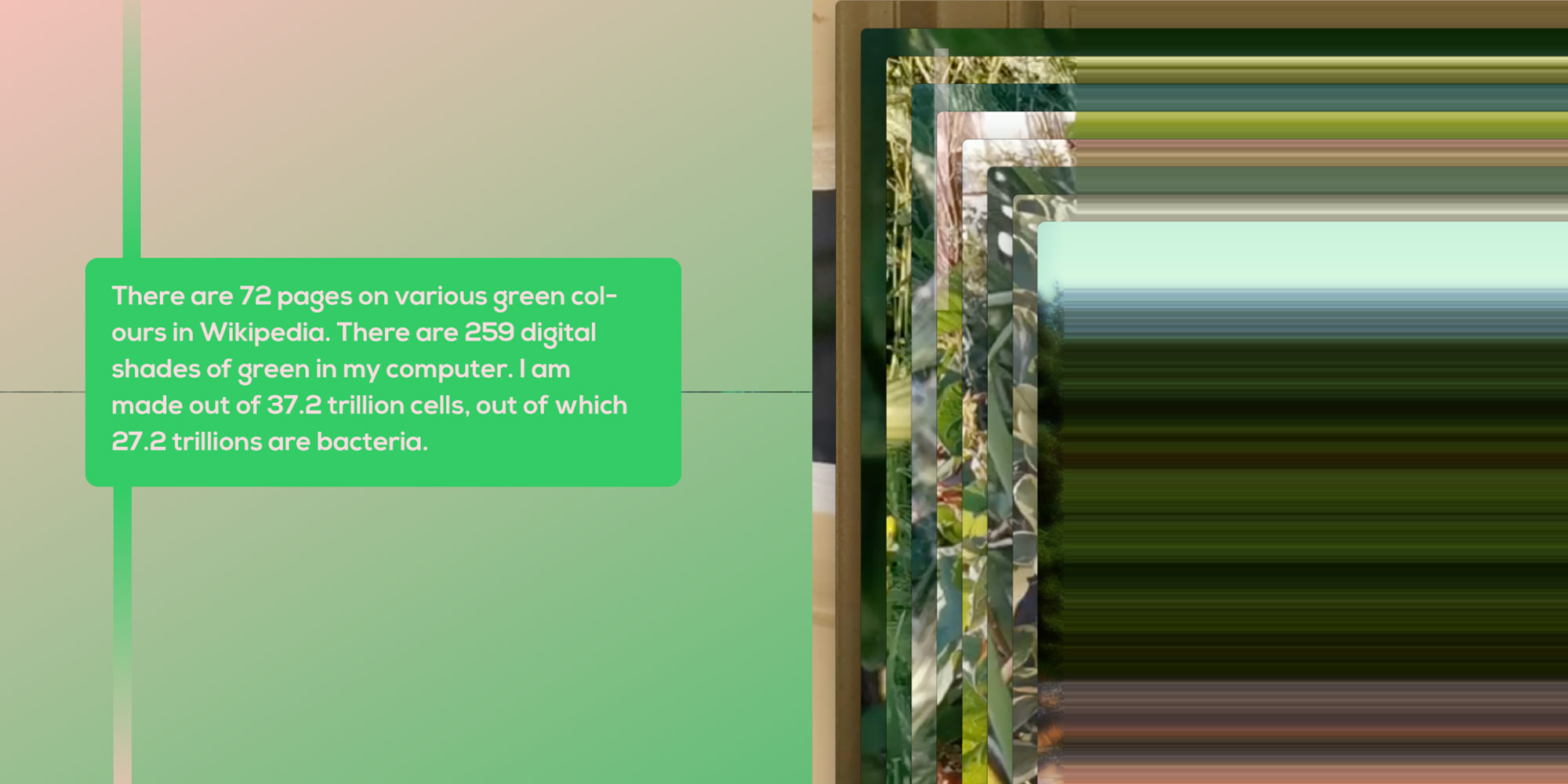

One more work happening at this moment is “Natural Glitch” – which is a novel co-written with my fellow artist Ivan Henriques, first chapter of it being commissioned by FACT in Liverpool. The first part has debuted at the Ars Electronica festival this year online as a kind of audio visual reading experience. This work was also a result of re-thinking my own relation to the natural world, science and my own creativity during the lockdown, and I am sure Ivan’s inspiration for it came from a similar place.

Natural Glitch, screenshot from the interactive online story, Credit: Kasia Molga

Natural Glitch, screenshot from the interactive online story, Credit: Kasia Molga

You presented “Human Sensor LDN” at the Ars Electronica Festival 2018 and dealt with the topic of air pollution. Do you see media art as a means of drawing society’s attention to the (environmental) problems that currently prevail?

Kasia Molga: I also presented Oil Compass as a part of “Protei” in 2012, when we received a Honorary Mention in the category of Hybrid Arts. While Human Sensor deals with air pollution and its impact on the human body, Protei and Oil Compass were about the offshore oil spills.

“To answer this question however I would like to first state that in my opinion it is not a primary role of art, whether so called media art or fine art to be didactic and it never should be used a “promotional vehicle” for any subject. For me art is about commenting on human and non-human conditions and experiences, revealing hidden interconnections, creating narratives about complexities which might be normally obscured and in result proposing alternative scenarios.”

I remember learning at my university during the arts history classes on religious icon painting that regardless of artists’ faith (or non-faith), we all just like icon painters, through our practices propose a window to the alternative universe through which we can reflect back on our current position. I feel this is the most powerful role of art.

Media arts, because of the tools and subjects present within it and because of its interdisciplinary nature – mixing arts, design, technology with science indeed can provide a platform to, for example (within my own practice), the real time data stream coming from various environmental processes – such as turbulences of air around us, full of invisible particulates; or enables us to zoom in real time onto the oil spills in distant locations.

Kasia Molga, Human Sensor LDN, 2018, Credit: Angela Dennis, courtesy of Invisible Dust

Kasia Molga, Human Sensor LDN, 2018, Credit: Angela Dennis, courtesy of Invisible Dust

Mixing scientific tools to examine the environment with the artistic way to render and interpret the results of these examination allow me to have a look at the interconnected mesh of all living and nonliving beings (I am referring here to Timothy Morton’s definition of mesh and interconnectedness as an ecological thought) and scrutinise my own – human – position within this, often disrupted by layers of human made systems – products, technologies or rules often obstructing the access to even tiny understanding of this interconnections.

That can be applied not only to drawing attention to the natural environment, but also to man made cities, digital spaces etc. And that way through at least what I do I hope to encourage informed and perhaps, for the lack of better word, emotional involvement in these subjects – so we can make sense out of them, and thus have some agency over them.

What are your plans for the upcoming EMAP/EMARE residency here with us? What do you want to do during this time?

Kasia Molga: I started to answer this question at the beginning of March according to plans set out earlier in the year. Needless to state that a lot has changed since then.

My concept “How to Make an Ocean” has been deeply rooted in grieving a loss of 3 close to me people in Autumn 2019. I have cried many tears in winter months while dealing with this, and at some point I started to collect them in a small container. I also was reading “Flights” Olga Tokarczuk (Nobel Prize in Literature 2019) and there was a short story where this very question was posed. It struck a chord with me because I spent my childhood on the open ocean, I live by the sea and sea is a huge part of my life.

And in my practice as I mentioned before I look for this very faint but vital interconnections between us – humans and the natural environment and so my first thought was whether while I produced so much of tears – which after all is a liquid – could I somehow contribute to growing and caring for a marine ecosystem.

Expanding from that I started also looking at environmental loss and anxiety and how this affect many people; and role of technology – for example AI – in creating narratives which might reinforce paralysing sensation of fear by curating news stories (i.e. the doom scenarios of the echo chambers such as facebook when one starts to read environmental news). That is not to say that the seriousness of the environmental destruction doesn’t exist, but the way my “news feed” for example was narrated meant that there was nothing more we could do but to give up and wait for an inevitable apocalypse.

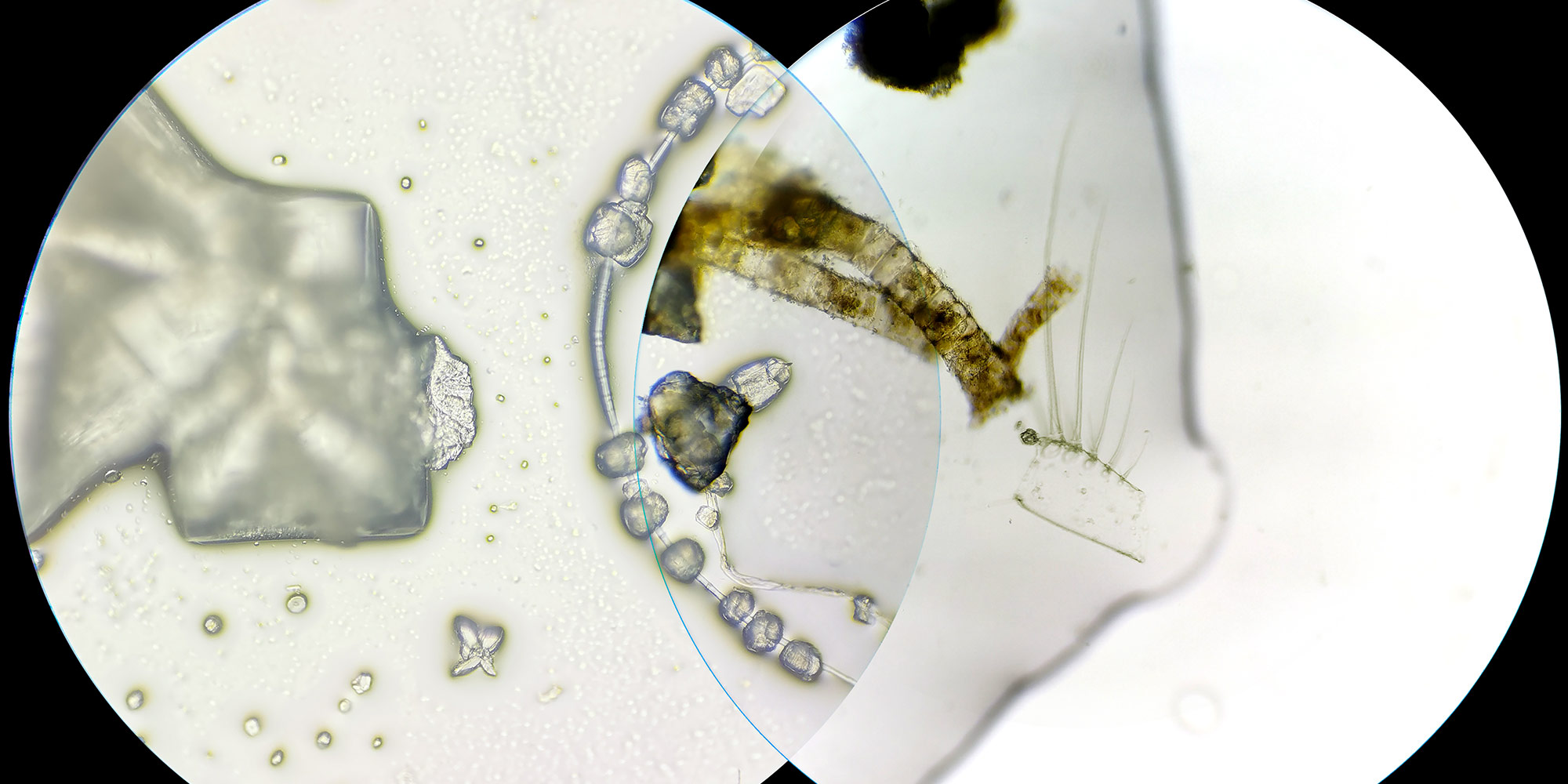

microscoping image of a drop of sea water mixed with the artist’s teardrop

microscoping image of a drop of sea water mixed with the artist’s teardrop

I started to question whether there is another way of using technologies to create a space for expressing emotional response to this loss through a sort of cathartic ritual, where tears and crying can be a part of it, where vulnerability wouldn’t be a sign of weakness and giving up, but genuinity and empowerment. It is also an investigation into the place of care and empathy, while giving a space to emotional upheaval – usually absent from the debates about the role of “tech and innovation”.

And a link with weird and fascinating “jobs” from the past – such as a moirologist – a professional mourner, invited to participate in wakes and funerals in order to help others mourn and grief over the beloved departed.

There is a widely documented research on the benefits of tears – from getting rid of the toxins created by fear or stress, to gaining mental clarity or easing physical pain (tears caused by physical suffering contain a natural form of painkillers). In Japan for example there is a practice called “rui-katsu” (tear-seeking) often arranged in corporate environments, to relieve employees stress levels.

Most importantly this work is for me about how we – humans – while destroying the environment – can contribute to its regeneration, using limitations of our own selves – our bodies. And it also touches on the concept of “circular economy” – the tears are the result of stimuli, often induced by things happening in our surroundings and so their “quality” or chemical composition vary.

Can our human body be a beginning of an external eco-system – and if yes – what it would be like? Besides I love discovering and observing all amazing invisible human eye creatures under the microscope, it feels like I am letting into some secret – a matrix of a sort which works tirelessly to keep our biosphere alive. And so I wanted to utilise this passion to reveal this hidden worlds and the impact, good or bad, we might have on it.

The residency was supposed to be executed in two parts – in the first part I wanted to investigate human tears and their chemical and physical properties and what marine species they could support. I also planned to create a tear collecting device – a modern take on lachrymatory, to collect my own tears and tears of other people. The second part of the residency is about investigating the aforementioned role of tech in an attempt to build an AI moirologist – a crying bot to help us all shed some tears.

This initial plan has naturally been altered by COVID-19 and international lockdown, but also it brought new angle to this work, while, in my opinion, reinforcing the need for a place to cry, grief, and to embrace the loss within our – now even more with so many things and experiences moving online – technologically mediated reality.

“There has already been a rising level of anxiety not only because of the fear of contracting COVID-19, but because of the changes we all had to endure for this new world order, caused after all, by a tiny invisible creature which was let out wild by our own reckless destruction of the natural environment.”

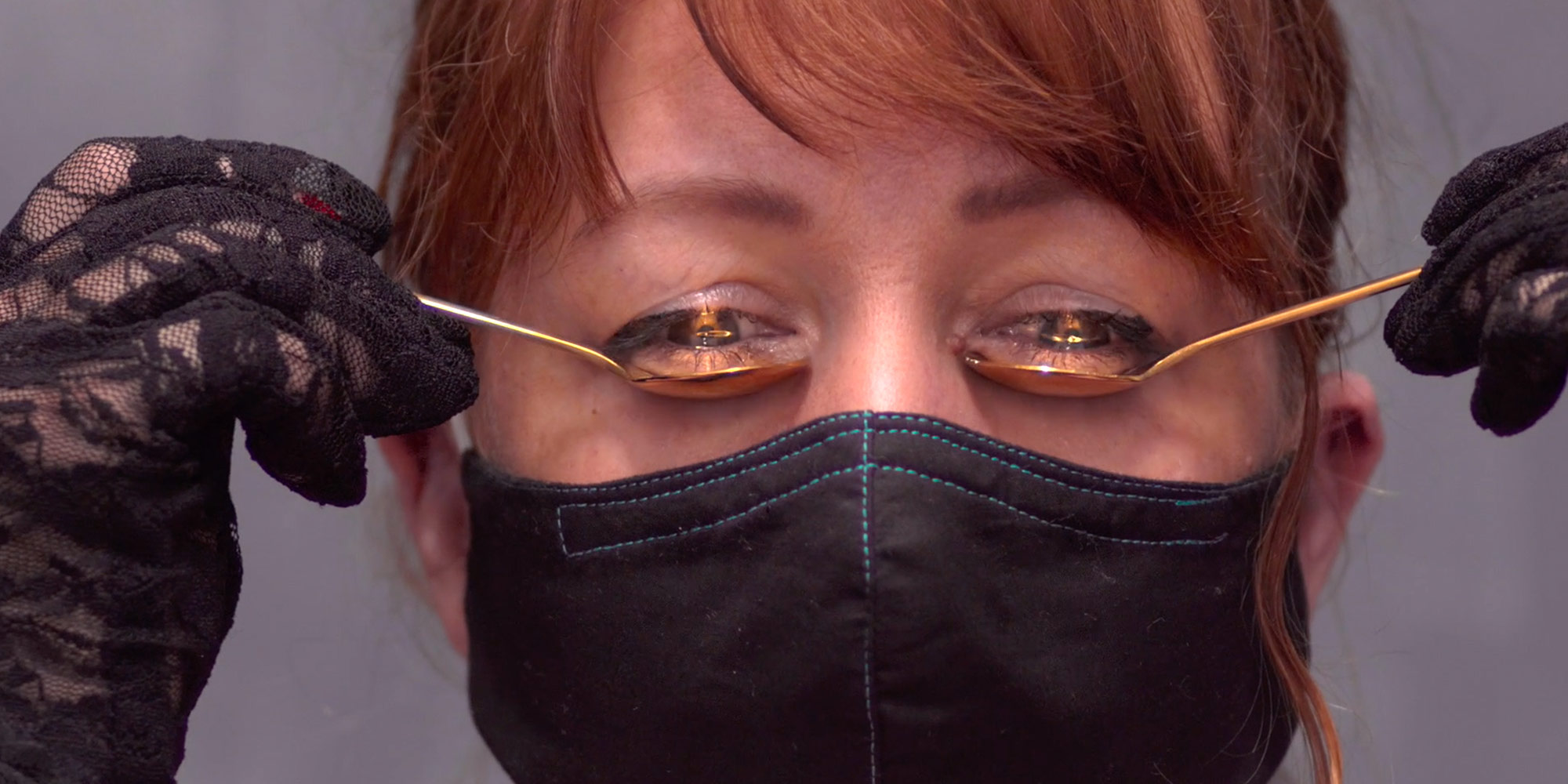

Still from the artist’s journey, a film commissioned by Ars Electronica for the Ars Electronica Festival, Credit: Kasia Molga

Still from the artist’s journey, a film commissioned by Ars Electronica for the Ars Electronica Festival, Credit: Kasia Molga

Naturally I couldn’t come to Linz to conduct my residency in the Ars Electronica labs, so I had to create my own make-shift lab in my studio while also trying to plan for the more online edition of the work.

The making of “How to Make an Ocean” has been much slower than initially anticipated, but it is a good thing because it has allowed me to embrace all these new developments and observations. In my head I see it as a multi-facade installation – combining an array of media in physical and online sphere which will hopefully premiere in Halle in 2021.

If you look back on your first media art works and compare them with today, what has changed – or rather, what tips would you like to share with emerging media artists?

Kasia Molga: It is a good question, which made me stop replying to this interview and instead reflect for a few days. I guess it is difficult to answer it properly without the context – i.e. how I arrived at the so-called “media art world”. In general I try to avoid “categorising” my work especially because I oscillate within quite a few disciplines – and borrow from each of them. Then again most of my contemporaries work in similar ways. I call myself a design fusionist due to various roles I take, and also “serial beginner” due to the fact that I seem to refuse to specialise myself in anything because I find too many things too interesting.

As far as I remember in my practice I have been dealing with the idea of interconnectedness and the first installations (in a form of more traditional form) were looking at animations and single cells of animations to be distributed around the world in such a way so I could wrap an animation around the Earth. That was then translated into the network based work – using MMS and SMS – investigating aesthetics of networked platforms and real time connectivity and how it can influence my form of expression and give some control for the experience to a viewer/participant.

In general looking back now I was playing with the idea of a democratisation of the artwork to some extent, where part of the meaning was conveyed through contributions from the audience. At the beginning also I think I was more concerned with the investigation of creative possibilities of emerging technological devices – so while this theme of interconnections is present always, it was skewed towards the tech I wanted to use.

Most of the first work is screen based – or 2D visuals (naturally I studied visual arts and design), but then I started moving more into critical approach towards tech in general – thinking about how to hack it to reveal obscured from viewers/users mechanisms which could influence our POV or relationship with system, environment and each other; and now frankly I am mostly focused on what I want to convey and don’t take care about tech so much – tech is not the main subject, but if appropriate it can become part of the narrative and a platform to demonstrate it.

I am less scared about not being labelled – in fact i don’t care anymore. I keep learning all the time – and often get frustrated with new pieces of code which I cannot figure out. But also with time I managed to get a fabulous team of people I collaborate with on a regular basis – something which obviously I didn’t have before. And so my role also changed from Do It All by Myself to a sort of art director and so often my work is a result of intense and deep collaborations with others.

(De)Compositions by Kasia Molga & Scanner, in collaboration with GROW Observatory, supported by STARTS EU. Photo from the State Studio exhibition Near+Futures+Quasi+Worlds, Berlin, 2020

(De)Compositions by Kasia Molga & Scanner, in collaboration with GROW Observatory, supported by STARTS EU. Photo from the State Studio exhibition Near+Futures+Quasi+Worlds, Berlin, 2020

What I would like to tell emerging media (and not only) artists is that this field is precarious and can be exhausting. A lot of people in this sector are on the verge of burnout or experienced one – and this is wrong.. One reason for that is that we don’t seem to know – from the perspective of an artist but also institutional cultural worker – how to value our artistic work. Recently I started to strongly believe that how to value our job of being an artist must be an elementary lesson in any art/design/creative school. And so my advice to younger people is to never agree to exhibit or work for free – your work is important, valid and powerful. Especially now – seeing what is happening just after the lockdown and how many people within the art and culture sectors are faced with struggle to keep afloat – we need to come together to demand respect for what we do – it is a job like any other, and we deserve financial security.

Other advice would be to get out of your comfort zone – go for subjects which you wouldn’t normally go and be ready for a good constructive criticism. Rejections are part of preparations – so welcome rejections too and keep trying. Also do not waste any minute on people with too inflated self-importance who do not listen – you will never learn anything valuable from them.

Be professional – borrow ethics of work from a regular corporation – value your time, learn how to charge and learn how to pay, respect teams who can help you make your work happen – this is you collaborators or institutions producing or exhibiting your work; learn how to write and respond to briefs and how to respect others time and property.

Most importantly – the tools and technologies which you might be using today, will be obsolete tomorrow – don’t fret but learn how to preserve your work as a one unit (i.e. store OS, hardware and software versions). At the same time, respect and cherish the Open Source and Hardware community – who might help you when your tech disappears into an abyss! Always give back and collaborate.

Kasia Molga (PL/UK) is a design fusionist, a serial beginner and master of none, out to question the impact of technology on the environment and its role in our relation and perception to “non-human makers.” She moves across disciplines to communicate complex ideas through tangible multisensory hybrid installations. She has exhibited worldwide, and presents and publishes regularly. She is also a licensed scuba diver, an avid aerial photographer and spent her childhood sailing on merchant marine vessels.