“You are part of a huge weave, that you cannot ignore anymore.” When you enter Diane Cescutti’s website and her work, you enter the world of weaving.

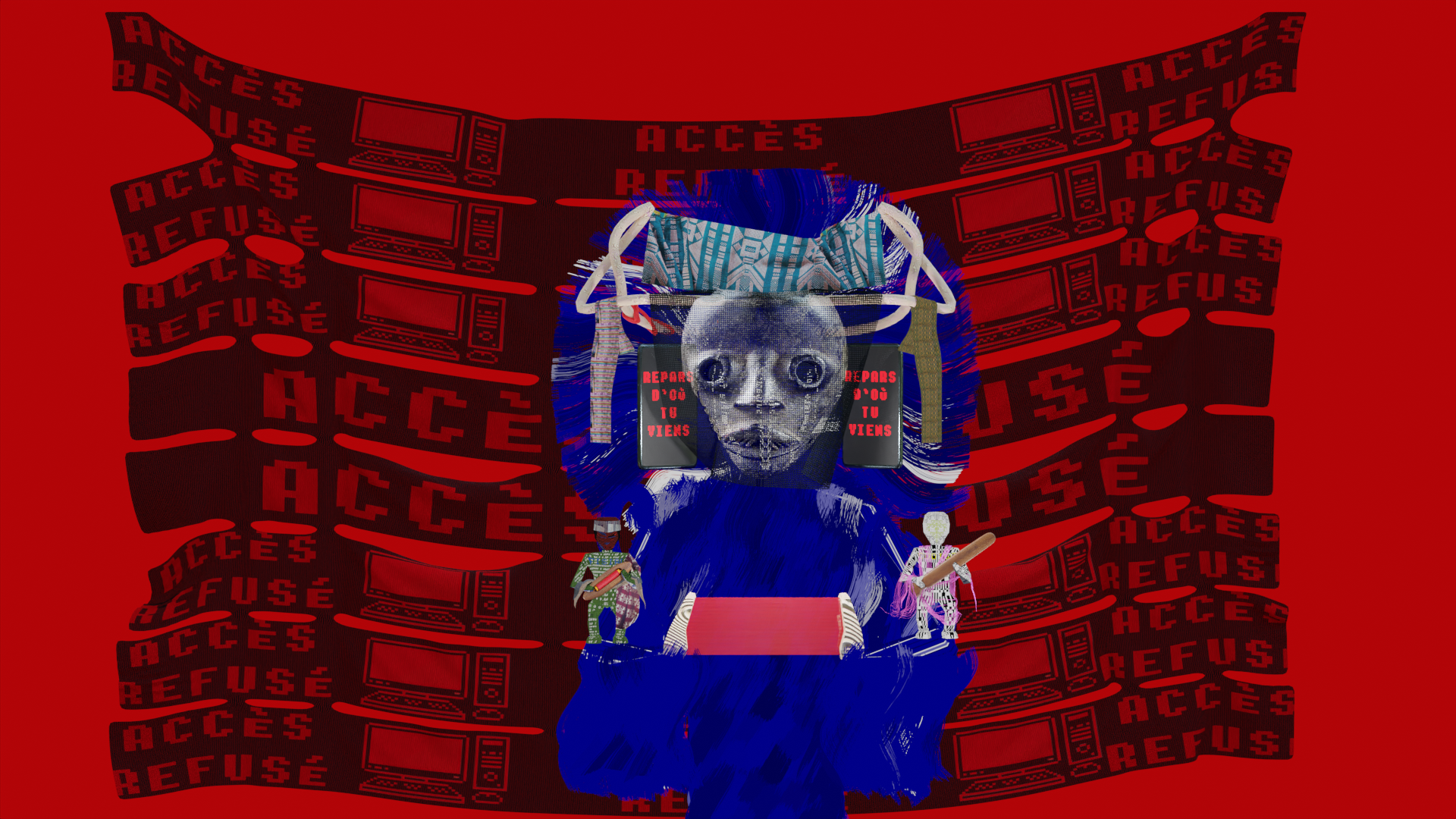

Nosukaay, the machine deity, narrates a story about an alternative history of computing, highlighting the links between computers, Manjak weaving knowledge and mathematics. The narrative combines texts, 3D images and images shot in the Aïssa Dione Tissus studio and the Boulevard Canal4 outdoor weaving studio in Dakar, Senegal. And you can only successfully master this world, the artwork and the game she has created, if you honour the art of weaving in the same sense that West African culture does. Otherwise, you are catapulted back to the beginning and have to do it all over again.

“If users make a choice that does not respect the machine deity and the importance of the knowledge transmitted, they get ejected from the game and must restart from the very beginning”, says Diane Cescutti. “This aspect of the experience is very important. Traditional and sacred knowledge cannot be transmitted unconditionally – a relationship of trust must be established.”

Cescutti won the Golden Nica of the Prix Ars Electronica 2024 in the Interactive Art + category for this interactive installation, which is a first attempt to create a modified “computer” – a textile machine that combines a West African loom and a computer. We spoke to the artist about the cultural significance of weaving, the user experience and how to get to one of Nosukaay’s beautiful endings.

What does weaving mean to you personally, but also in a cultural context?

Diane Cescutti: Personally, weaving really symbolises the power to connect things without destroying them, it’s a story of arrangement, it’s an “ordorer” and a bridge between the material and the digital because of its mathematical and algorithmic properties.

One important thing is its thickness, I think touch is one of the most important senses to be immersed in a space, because we’re always touching something in the world and being touched back. Somehow the texture and tactile properties of this ancient code have been completely erased by the digital. Despite the name, the tactile feedback of digital technology is quite poor.

Weaving is a common denominator of many human societies, there are really very few civilisations that do not interweave threads. Many indigenous cosmogonies and mythologies also contain references to threads, textiles and weaving. The meaning of weaving varies from culture to culture, but it’s interesting to see how it always carries deep social values and symbols.

What is the relationship between weaving and computer technology in your work? How do the two different technologies work together? What does this connection mean in a broader sense?

Diane Cescutti: Weaving is the ancestor of the computer, this is the premise of my work. The problem is that the contribution of weaving to computer technology has been partially erased, so I’m trying to dig up those links and also create new ones, thinking about what weaving can tell us about computers now, but also the opposite. With a historical-futuristic approach, I go in both directions. I mix both technologies by creating e-textiles, weaving that becomes an interactive keyboard, creating mathematical woven texture in 3D, using cables as threads for weaving and turning physical weaving into 3D assets.

In a broader sense, I use this connection to question our current technologies and to raise awareness of how their design, haptic properties and shells could benefit from a return to the softness, versatility and resilience of weaving and textiles.

What can the player experience when playing / interacting with your installation?

Diane Cescutti: The first thing is the texture under the hands. Compared to a normal keyboard, you don’t have this uniform basic sensation, there is a thickness and a texture, then you can also experiment with different kinds of strokes, you can press the keyboard, caress it, tap it, use your palm, your fingers, the back of your hand…

The second thing is, of course, the video game and the visual experience. The player is invited to navigate the story of Nosukaay by making different choices. Depending on these choices, different paths are opened up, depending on the level of trust between the god of the installation and the player. More or less will be revealed accordingly. Players can also be “kicked out” of the system if they choose an option that creates mistrust with the god of the video game; they are sent back to the beginning and can start the game again if they wish.

At one point the following text may appear: “Honor and protect information. You can never fully grasp the code you operate. A part of it is always hidden from you, the unspeakable, the back, the reverse. You’ll turn it over in the end. Those who don’t weave don’t know that we always turn our fabrics inside out. If he comes to see the machine, the loom, the source, he doesn’t see the resemblance between the fabrics he saw at the market and those being made.” Is this your message – to honor and protect cultural heritage, ancient traditions?

Diane Cescutti: That is part of the message. This artwork touches on many aspects of systems thinking, following the writings of Donella Meadows, an American environmental scientist, educator and writer who is a pioneer in systems analysis and dynamics, but also talks about preservation.

What I want to say is that it is subtle. I think it is important to preserve them in a way that honours and respects the information they carry and the way they are made. In the case of manjak weaving, it is important to protect the way patterns and designs are transmitted and stored, and the way the craft is taught to apprentices. Manjak weaving is done with the back of the fabric facing the weaver, it’s not something you can guess by looking at the fabric alone, so it’s important to preserve the weavers and the technique, not just the objects.

And at another point the “game” says: “Before wanting to change it, pay attention to the value of what is already there. Our random access memory works without electricity, we remember patterns transmitted from generation to generation and that is how our systems persist in a state of self-maintenance.” Who or what wants to change the system, you think, what are you referring to here?

Diane Cescutti: I think in the Occident there is this culture of control, and that ends up with people who, when they interact with traditional crafts, sometimes disregard what kind of system is in place socially and technically because it seems too chaotic in their eyes.

Manjak weaving is a weaving technique with a whole ecosystem of people, every aspect is important and should be considered because changing one element could end up dramatically affecting the whole system in place. I’m not saying don’t change anything, but really pay attention to what is in place before trying to improve any kind of system.

There is a cautionary tale in the history of weaving: Jacquard, when he invented the Jacquard loom, wanted to improve the working conditions of the weavers in Lyon, especially the children. Child labour was very common because weaving was a family business. The jacquard loom replaced the children who lifted the threads of the pattern, but the devaluation of the price of textiles did not allow these children to stop working and they ended up taking other more precarious jobs outside the safety of the home.

In addition, the combs shown in your project video contain messages – how do they contribute to the story of the installation?

Diane Cescutti: The combs represent different guidelines given by Donella Meadows in her text: In “Dancing with Systems” she teaches us that we can’t fully understand systems, but we can dance with them. Computers, no matter how powerful they become, will never be able to give us the key to prediction and control, simply because there is no such key. I think weaving fully embraces this, the algorithm of weaving, the various mathematical steps that create a textile are rigorous, but the threads to which the code is applied are soft and twisted. They are not perfect lines. Weaving is all about the fact that you can control the threads completely. In a way, I can also say that the guidelines on the comb give you hints on how to reach one of the beautiful endings of Nosukaay and not be thrown back to the beginning of the game because you failed to respect the knowledge that this artwork gives you.

Diane Cescutti

Diane Cescutti (FR) born in 1998, is a French transmedia artist. She lives and works in Saint Etienne, France. She studied Fine Arts and textile in the École des Beaux-Arts de Nantes in France, Tokyo University of the Arts in Japan, and in the University of Houston in the United States. Her practice starts from the loom at the origin of computation. By tracing the history of computer code, she finds herself entangled in the world of weaving, and by following the crossing of the fibers of her loom, she ends up at its ethereal form: its algorithm.