Since March 2024, “Planet Ocean” has been inspiring visitors to the Oberhausen Gasometer with its giant ocean projection “The Wave”. Project manager Ina Badics and her team give an insight into the challenges and inspirations that made this unique installation possible.

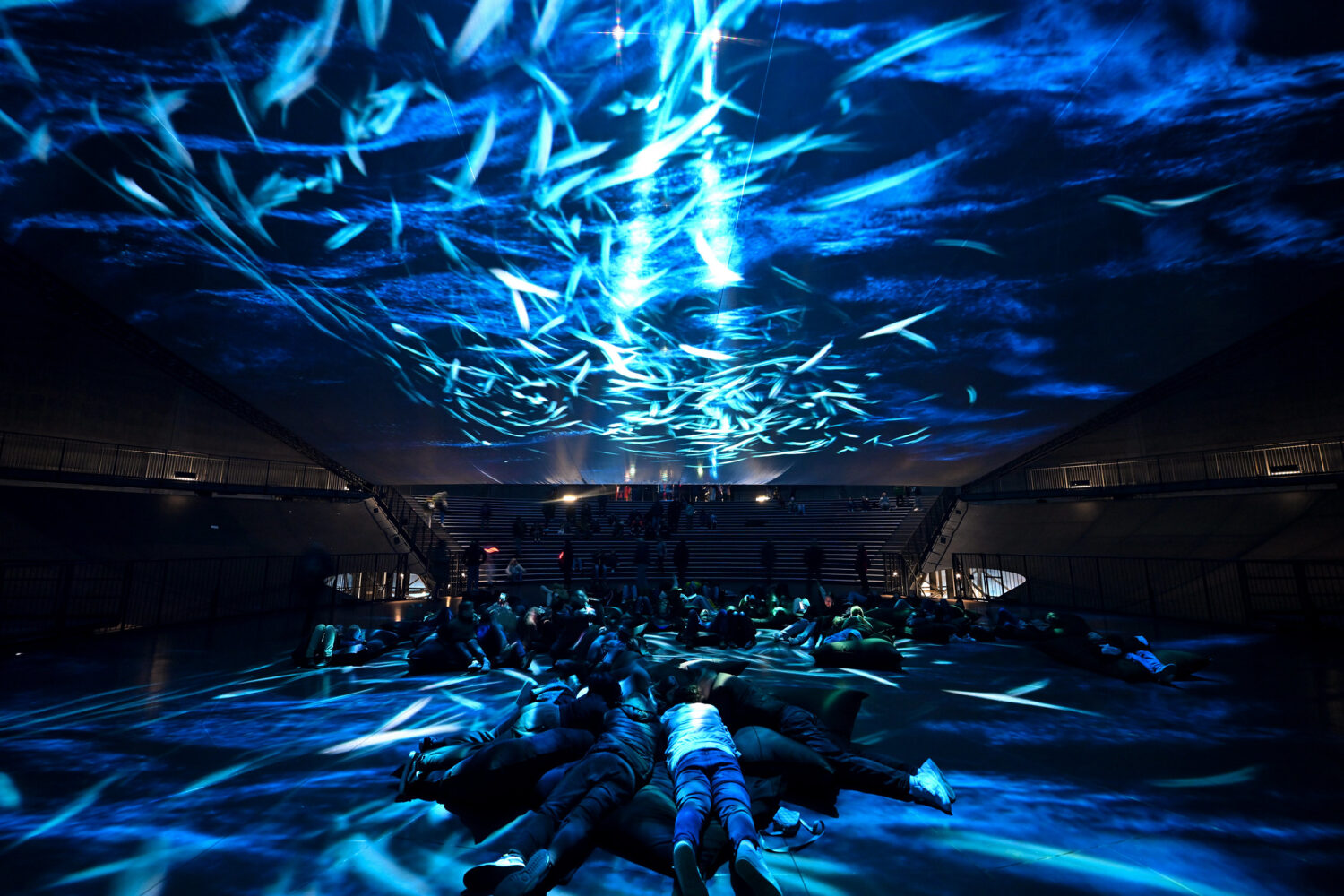

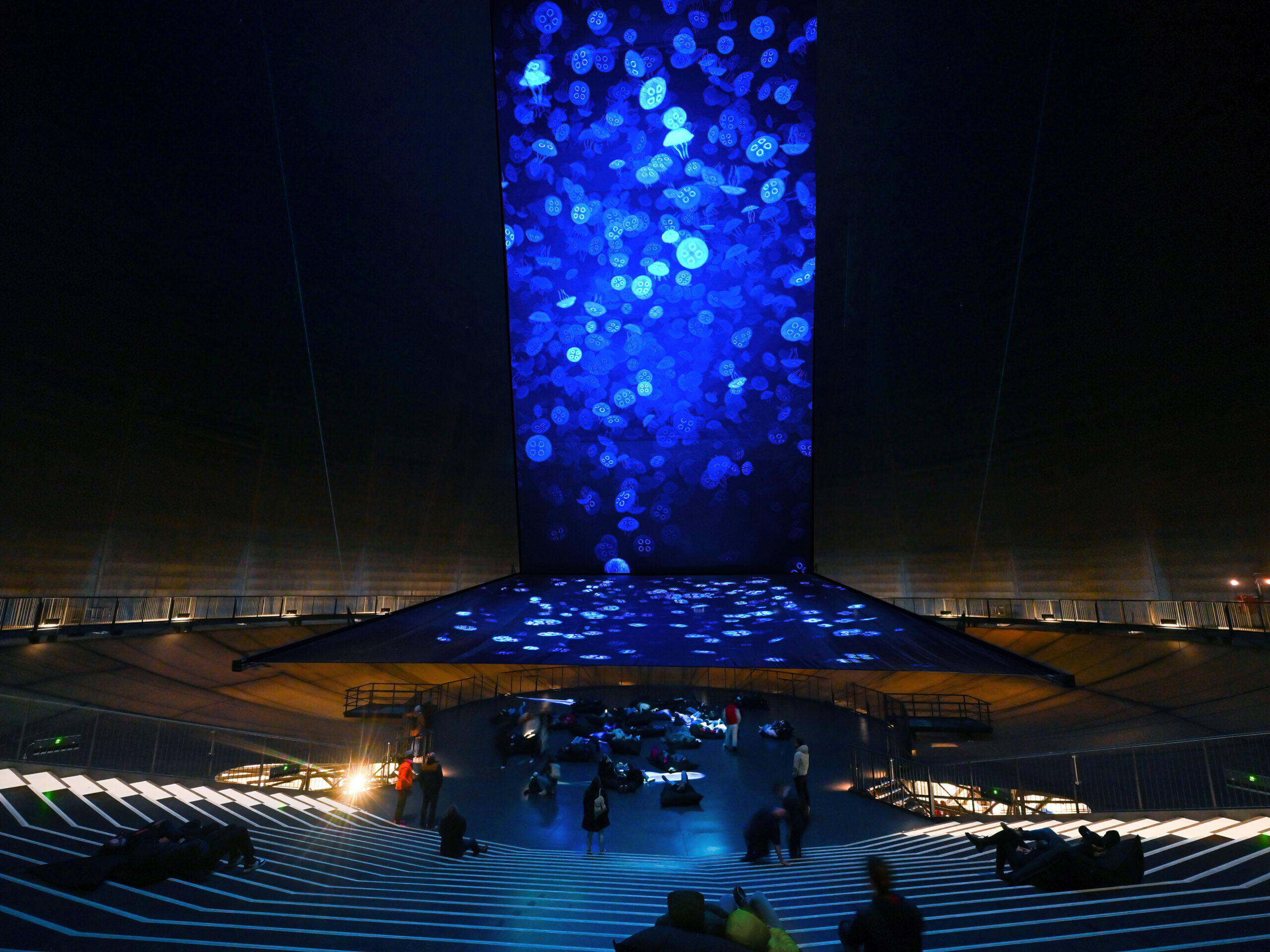

“The Wave” is the highlight of the “Planet Ocean” exhibition at the Gasometer in Oberhausen. The impressive 1,200-square-metre projection shows lifelike animations from the mysterious world of the sea. Ars Electronica Solutions conceived and implemented this masterpiece, which fascinates with its hand-crafted, creative scenes. Visitors can step under the horizontal screen called “Gaze” and enter the underwater world. Without the need for a wetsuit, they can experience the ocean at close quarters, with whales, fish and jellyfish. The visual spectacle is accompanied by an immersive sound experience that creates a special atmosphere. The unique industrial architecture of the gasometer enhances the experience: the projection of the ocean surface blends visually with the ceiling construction, giving the impression of being below the ocean surface. The successful combination of visual, acoustic and architectural elements creates an intense experience that leaves a lasting impression and awakens a deep emotional connection to the ocean.

Project manager Ina Badics, composer Rupert Huber, media designer Michael Wilhelm and media designer Markus Wipplinger, who was also responsible for the concept for this project, share the insights and experiences they gained during the creative process. They explore the inspirations, challenges and emotional highlights that shaped the design and realization of this unique installation.

We would love to know more about the creative process behind “The Wave”. What inspired you and what special approaches did you take in its conception and realisation?

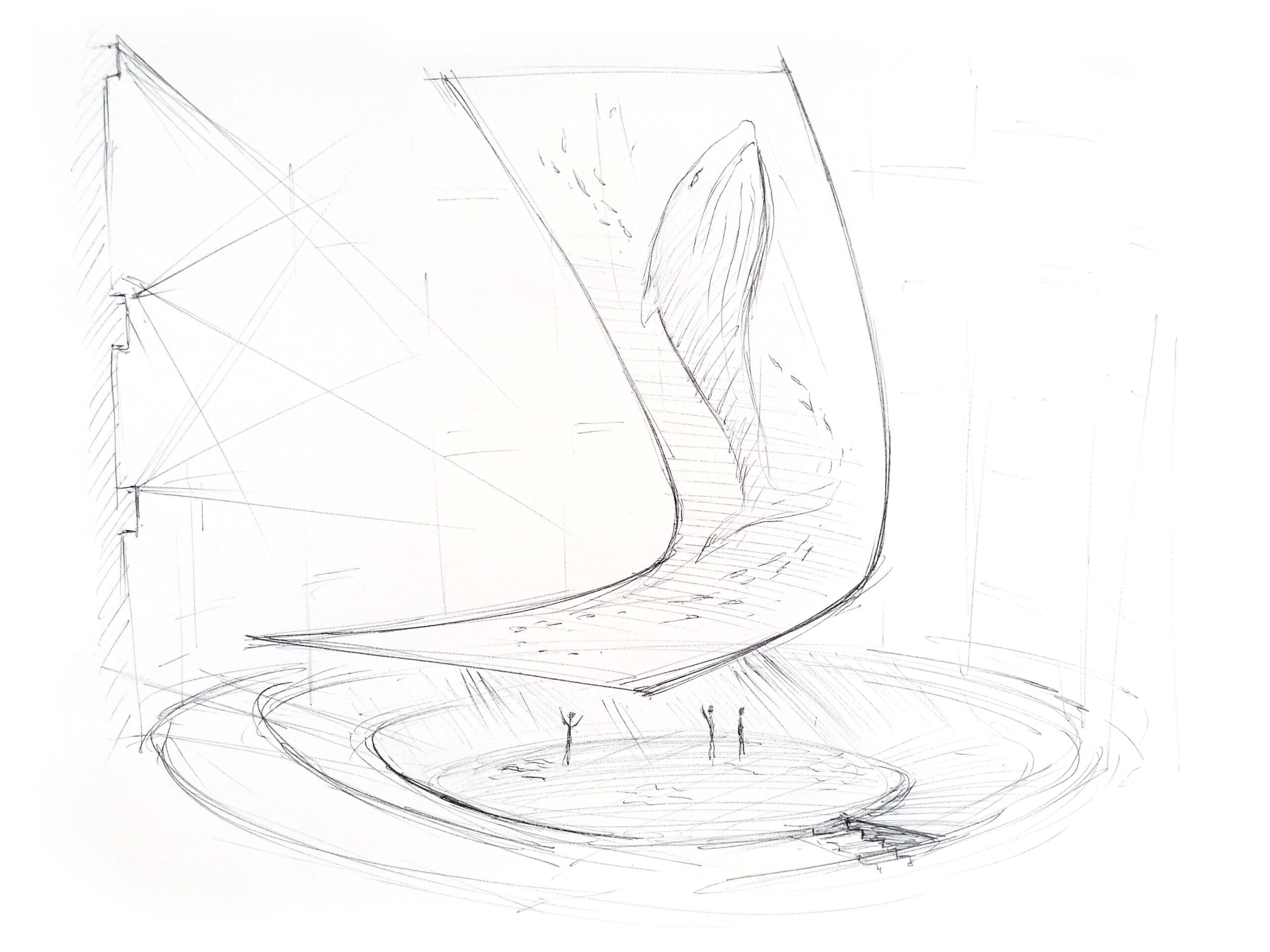

Ina Badics: Our main goal was to give visitors an immersive experience of an underwater world. To create this immersion in the depths of the sea, we needed to find a way to symbolically take visitors below the surface. The solution was a wave – a fascinating combination of power, movement and aesthetics. Waves embody the tremendous energy and dynamism of the sea, and it was this feeling that we wanted to capture.

Markus Wipplinger: The space of the Gasometer was an immense inspiration in itself. When you enter it for the first time, you feel very small – almost like in a huge cathedral or an oversized submarine – oppressed and weightless at the same time. We wanted to play with the dimensions and give a sense of the infinity and depth of the ocean. To enhance this effect, we used visual tricks by slightly tilting the 40 metre high screen to make it appear to reach the 100 metre high ceiling of the gasometer. The shape of the projection surfaces is based on a standing wave, which breaks over the visitors as an elaborately simulated animation, taking them on a journey into the depths.

How do you see the role of the connection between art and technology in a project like this, which allows visitors to immerse themselves so deeply in the underwater world?

Ina Badics: In this project, technology served as a tool to bring the artistic vision to life. The aesthetics and the immersive experience for visitors were always at the forefront, but the technical implementation was developed from the outset as an integral part of the artistic idea. Art and technology went hand in hand to create a profound, sensual experience.

Markus Wipplinger: Our aim was to intensify the visitor’s sense of body and space and to break viewing habits. 3D glasses or similar technologies were out of the question. To achieve maximum immersion, we experimented with different media and materials, ultimately creating three visual layers that complement each other. Depending on the visitor’s position, different impressions are created. Movement in the space creates parallax effects that create depth and enable holographic effects. Visitors become directors, immersing themselves in the visualisations and actively taking action. In the final act, they use a tracking system to generate bioluminescent particle streams that rise from their position.

“The Wave” and the rest of “Planet Ocean” do not feature any live animals, even though the exhibition is about life in the ocean. What do you think of this? What makes this decision so special for the experience?

Ina Badics: To truly understand the magic and importance of nature, we need to experience it directly and deeply with all our senses. The exhibition reminds us of the incomparable beauty of our planet and how precious and worthy of protection it is. By preserving this splendor, we carry the hope of a livable future for generations to come. The exciting thing about this decision is that it addresses the dilemma we often face as humans: In our attempt to understand nature, we often intervene in it and change it. This exhibition avoids this by artfully depicting nature without directly interfering with it, and invites us to preserve it all the more carefully. It is a challenge and at the same time a special experience to invent artistic and technical means to recreate such a sensual experience. The trick is to stage nature in such a way that it triggers the same emotional depth and fascination without being real – and yet still allows for an intense experience of nature.

What makes the animation in this project special, and what aesthetic or emotional advantages does it offer visitors over real video footage?

Michael Wilhelm: A particular challenge in this context was the limited time available, which made it almost impossible to produce material in a ‘finished’ state in advance. Through real-time simulation and pre-production of the individual content parts, we were able to create as much as possible in advance and at the same time test and adjust the essential parameters such as swarm size, fish numbers, speed and spatial distribution on site.

Markus Wipplinger: Due to the gigantic dimensions of the gauze and canvas, as well as the unusual perspectives that visitors experience, normal film recordings would be perceived in a distorted way. The camera positions and lighting moods were specially optimized for the angles of the screen to make animals and plants appear in real size and to allow the light to come in centrally from above – an imaginary water surface. The gauze and canvas were aligned so that they correspond to the godrays of the projector positioned at a height of 80 meters and form a sculptural unit with the play of light. In addition, the gauze presented further challenges: shadows are transparent on the transparent fabric, and the same motif also appears on the floor. So a compromise had to be found in the lighting in order to make the scenes appear credible on both media.

What were the unique challenges in developing “The Wave”? What technical and creative hurdles did the team have to overcome to make the animations so realistic and immersive?

Michael Wilhelm: The most complicated technical problems occurred with the jellyfish: thousands and thousands of animated jellyfish instances with transparent materials under water. Balancing natural chaos with necessary scenic order in combination with the systemic superstructure of the jellyfish particle systems was particularly challenging. The goal was to create sequences as long as possible without cuts, while also producing a credible transition from the sea surface to the deep sea.

Markus Wipplinger: Because we could only simulate the perspectives inside the gasometer to a limited extent before the final construction, we had a very limited time frame in which to time the animations, set up the cameras correctly and finally render them. Due to the high resolution of the seven high-performance projectors, we had to work efficiently in terms of rendering times and break new ground. The fluid simulation of the wave required months of simulation cycles and several terabytes of simulation data before it could be rendered with the desired realism. The climatic conditions inside the gasometer were the biggest technical challenge. From tropical heat to freezing temperatures and condensation, all scenarios had to be taken into account. The tilted position of the gauze was therefore not only a deliberate design choice, but also important for water drainage.

How important is it in such projects to evoke not only aesthetic but also emotional reactions in the audience?

Ina Badics: For me, evoking emotions in the audience is the top priority. The harmonious combination of architecture, visual images and musical compositions creates a transcendence that is difficult to experience in everyday life. This emotional depth makes the experience special and leaves a lasting impression that goes beyond the purely aesthetic.

Markus Wipplinger: The strength of immersive experiences lies in the fact that they take you with them. You are more intensely involved in the journey to distant places and in the storytelling. Since the arena is freely accessible at all times, the staging begins individually for all visitors. Dramaturgically, the staging works in loops: waves build up and break, flora and fauna react to changing light and shadow conditions. Imposing giants are surrounded by dynamic swarms, hunting wildly while simultaneously floating weightlessly above the audience. You are in the middle of the action and become part of a larger whole that allows each individual their own personal access. Being in the thick of it makes individuals much more emotionally involved protagonists.

The audio component plays an important role in the exhibition. Can you tell us more about the immersive sound experience and how it complements the visual spectacle?

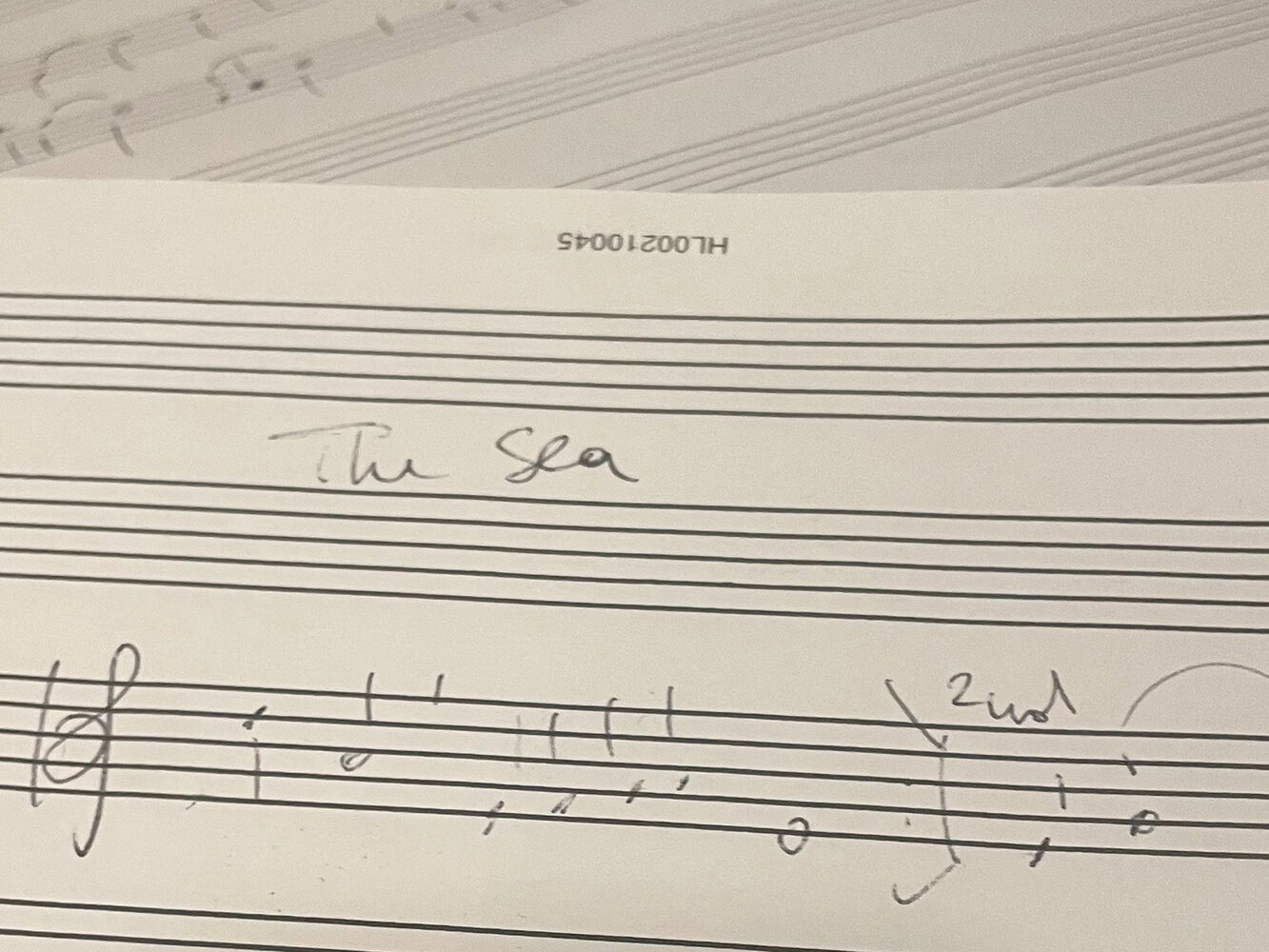

Rupert Huber: The composition of the music for “Wave” encompasses three central areas: spatial, emotional and sonic. The interweaving of these three elements creates an immersive experience for the visitor. The result is an independent level of perception that is symbiotic with the visual – a musical narrative that unfolds independently in space, parallel to the visual.

How were the sounds chosen to complement the visuals and create an emotional connection with the audience?

Rupert Huber: I imagined what an invisible ‘twin’ of the visible animals and plants would feel – for example, an invisible whale in the audience watching its twin swim across the screen. The music describes the inner life of the animals and plants as seen by the audience. The sounds of acoustic instruments were also processed in various ways to orchestrate this inner journey narrative in a compelling way.

How was the challenge of playing in a room with special acoustics and creating an immersive sound experience mastered?

Rupert Huber: The space of the Gasometer is unique in many respects, especially acoustically: an extremely long reverberation, which mixes with multiple echoes, makes composing a particular challenge. Thanks to my experience from working on the previous exhibition, I knew the peculiarities of the room very well and was able to use them to make the room itself resonate – to “make it sound”, so to speak. This turned this idiosyncratic room into a musical instrument!

How did the exhibition architecture influence your creative process? Did you have to adapt certain aspects to encourage interaction between visitors and the animations?

Rupert Huber: From the outset, the music was designed as an independent interpretation of the exhibition architecture. Since music creates a space in the moment, the musical architecture functions as the sonic equivalent of the architecture of the room and the exhibition. This self-imposed task formed the guideline for the compositional process; the music was

How did the various team members interact and collaborate during the implementation of “The Wave”? Were there any special moments or challenges?

Ina Badics: I would not be completely honest if I said that there were no challenging moments during the project. “The Wave” combined many different artistic and technical elements that are of equal value and can only work successfully as a unit. Time management and compromises had to be carefully weighed up. Despite these challenges, at the end of the day, everyone worked with a great deal of respect and empathy for the work of others. This collaboration has resulted in “The Wave” appearing to be cast from a single mould and functioning as a harmonious whole.

Rupert Huber: A project like “The Wave” can only be realised through teamwork. Such an intensive exchange between all areas – not just the artistic ones – requires a constant effort to find a common language, in the literal sense. For example, in music there are certain terms that mean something different in other areas. Particularly beautiful moments arise when this common language is used and something is created that goes far beyond one’s own area of expertise.

Do you have a personal highlight from the entire project that you would like to share? Was there a special moment that touched you emotionally or was significant for the team?

Ina Badics: A very special highlight for me was the touching embrace of a mother and her son, who were standing under the wave and diving into our journey into the ocean together. This moment was full of emotion and showed how deeply connected we felt to the installation. And of course, the opening itself was an unforgettable moment. Gazing at the end result together with the entire team touched us all deeply and more than justified the hard work that went into the project.

Rupert Huber: As well as experiencing the finished piece for the first time, the creative process on site is like an adventure trip – a joint expedition to the limits of what is possible, including the cold that prevails in the gasometer in winter. There were some moments when mutual support was particularly noticeable!

Markus Wipplinger: As a designer, I spent many days over a period of months in the gasometer, but only virtually and with many question marks in my head as to whether it would ultimately be as great as we imagined. After the first long day of the rollout, I stood alone in this huge colossus in the freezing cold for a moment. Above me, in the darkness, the wave floated weightlessly, like a contentedly sleeping, self-contained being. In that moment, I came to rest and was sure that something special would happen when this dreaming giant awoke.

How do you see the future of the connection between art, technology and environmental awareness in exhibitions like “Planet Ocean”? What new approaches do you think could emerge in the art world?

Rupert Huber: Personally, I see the combination of art, music, technology and environmental awareness as a way to shape our future, which cannot always be taken for granted. This happens through the possibilities of communication with people and through the feedback of interdisciplinary collaboration into the individual disciplines!

Markus Wipplinger: I am convinced that art and technology must, above all, be accessible in order to create a deeper awareness of important issues. In the Gasometer Oberhausen, this is done in a wonderful way, without a hint of a moralising undertone. True to the motto of the ocean: depth instead of aloofness!

Find out more about the project and the work of Ars Electronica Solutions here.

Ina Badics

Ina Badics has been a project manager at Ars Electronica Solutions since 2017. In her work, she focuses on the development of interactive and multi-sensory worlds of experience. Her main focus is on creating a central theme in the storyline, whereby the emotional depth of the underlying story is of central importance to her. She is passionate about every step of a project and ensures that her clients’ visions are optimally implemented through close communication. Ina Badics’ goal is to create experiences that touch the viewer on an emotional level. Her private life also reflects her affinity for creativity: she is interested in art, film and music, which provides additional inspiration for her projects.

Rupert Huber

Rupert Huber is a composer and best known for his piano music and music installations. He has been travelling the world with his electronic music project TOSCA for 25 years. He has become known for his numerous collaborations with Ars Electronica in the field of media art. For Huber, music is communication and an active state of peace. His compositional theory, which he calls Dimensional Music, takes into account physical space and unknown possibilities in order to create social and participatory musical architectures.

Michael Wilhelm

Michael Wilhelm is a multimedia artist with over 20 years of experience in various industries and in agency work. He completed his studies in sculpture and art education at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. The examination of current technology is a central component of his daily work. His focus is on 3D visualisations, animations and interactive media, with a particular emphasis on the use of real-time engines in the present and future.

Markus Wipplinger

After a traditional education in graphic and communication design, Markus Wipplinger learned to make his images walk in the multimedia art programme. He earned his first spurs in the Wild West at Buck in Los Angeles, before finding his professional home at Ars Electronica. Initially at the Futurelab and since 2013 as Head of Design at Ars Electronica Solutions, he has been designing and realising museums, events and brand lands – always with the aim