As curator in residence of the ARKO-sponsored Curatorial Residency Program, Son Hyerim was on site during the jury weekend of the Prix Ars Electronica. In this guest article, she shares her personal reflections on this experience.

For the 2025 edition of the Ars Electronica Festival, Hyerim Son joins the curatorial team through the ARKO Curatorial Residency Program. Her contribution draws from a practice deeply rooted in cross-disciplinary research and an interest in the transformative potential of exhibitions as sensorial and connective media. Engaging with media environments and embodied experience, her approach brings a nuanced sensitivity to how curatorial formats can reframe perception and foster new forms of dialogue. In the context of this year’s festival, her presence adds a critical perspective informed by both institutional experience and a commitment to experimentation—enriching the curatorial process with translocal insights and a reflective curatorial voice.

Guest article by Son Hyerim

“She no longer thought in language. She moved without language and understood without language – as it had been before she learned to speak, no, before she had obtained life, silence, absorbing the flow of time like balls of cotton, enveloped her body both outside and in.” (Han Kang, Greek Lessons, p. 8)

Han Kang’s Greek Lessons follows a woman who has lost her ability to speak and a man who is gradually losing his sight. Through Greek—a language once foundational to the architecture of human thought and existence, now considered “dead”—the two recognize each other’s wounds and come to understand one another not through speech, but resonance. The woman’s silence is not a collapse, but a reconstruction; not a disintegration, but an exercise in retracing the grain of the world. She once experienced the breakdown of language in her youth, but her silence marked not an end of negation, but a reorganization of sensation. Where the trajectory of words vanished, she began to relearn the density of the world with her fingertips, with her gaze, with the surface of her body. The man, who grew up speaking Korean before migrating to Germany, has inscribed multiple linguistic systems onto his body. Now, removed even from these two realms, he teaches Greek—a dead language—to others. The woman who cannot speak and the man losing his sight meet in their mutual sensory loss; together they inscribe language into the palms of their hands, transforming silence back into sensation and from that sensation, reassemble the world.

The disorientation of confronting vanishing vision and crumbling language—and the leap of possibility found in a dead language unfamiliar to both—resonated with the theme of “panic” for this year’s Ars Electronica Festival, and with my own body as it stepped onto Austrian soil for the first time. Participating in a curatorial residency through the collaboration between the Arts Council Korea (ARKO) and Ars Electronica Festival, I arrived in Austria in April to observe the Prix Ars Electronica jury sessions. That day, the scent of the air and the height of the clouds—both unfamiliar—pushed me beyond a threshold. At Vienna Airport, terminals connecting freely to other Schengen areas unfolded around me—an everyday scene in Europe. But for me, a South Korean unable to cross into the Eurasian continent by land due to the impassable North Korean border, it was a surreal and unfamiliar sight. I found myself easily transferring across boundaries I had never physically crossed—almost as if my body had

entered a new world of language and order for which it was not yet prepared.

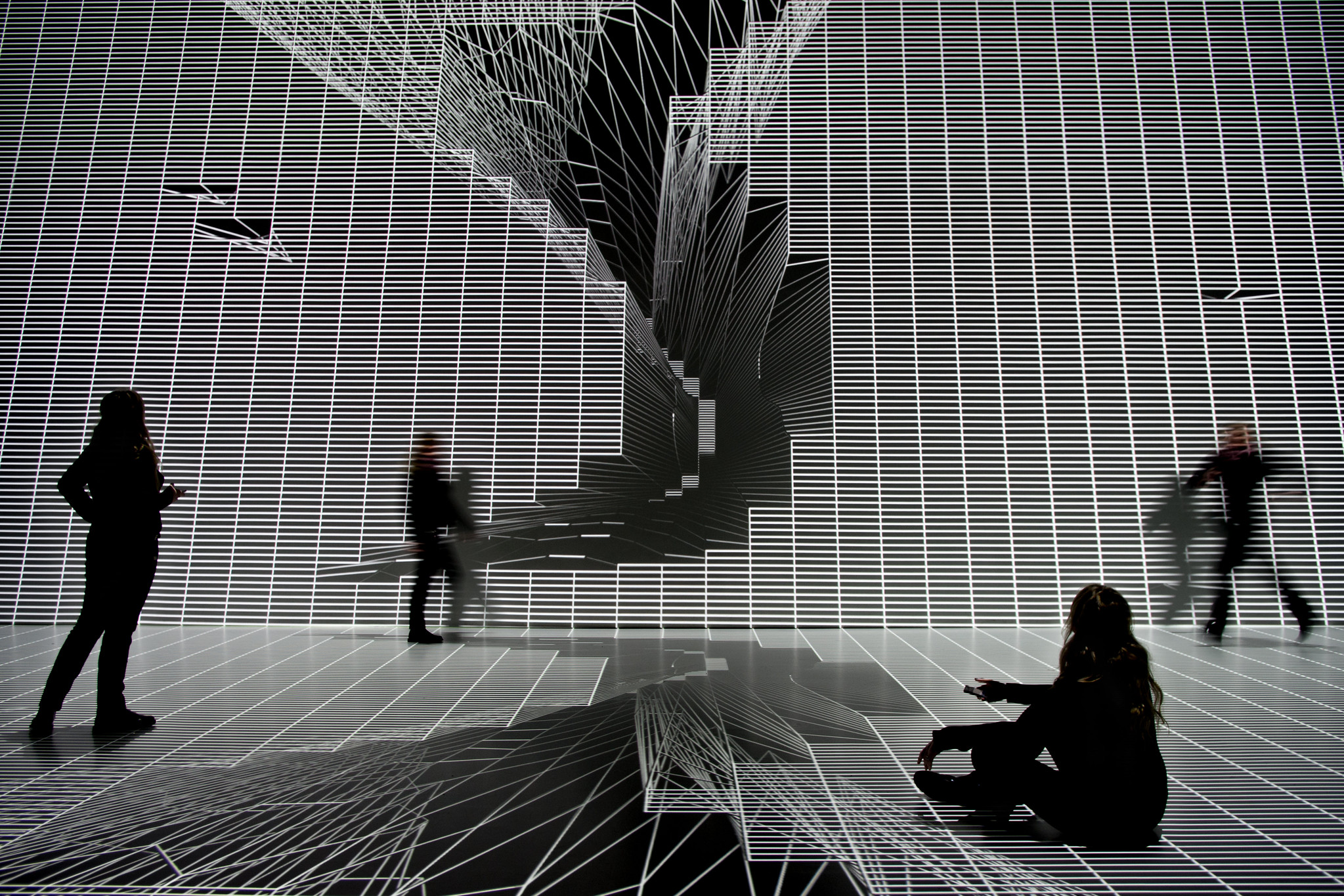

That unfamiliar sensation was as foreign to me as the Greek language the characters in the novel had struggled to navigate, and in a certain sense, it approached me as a form of panic. Panic is often described in terms of physical or mental breakdown, but I believe it ultimately emerges from a more primal, sensory layer—a sensorium attuned to rupture. Encountering phenomena beyond the images and information I had prepared in advance, I frequently experienced panic at a sensory level. However, it was through unexpected conversations during my early research trip, the warm gestures of welcome from the Ars Electronica team, and the silent dialogues I found myself having with the works encountered during the jury sessions, that my panic began to soften. It shifted—not into disappearance, but into a quiet unfolding of another way of sensing.

Though technological advancements now enable us to simulate prior experiences by querying AI or searching online, the prelinguistic sensations—the unquantified stories between people, the affective bonds to those pushed to the margins within digital saturation—remain vital. They persist as the foundational mechanisms through which we connect, empathize, and mourn. Perhaps this is why, despite the newest techniques and technologies, the micro histories of humans and nonhumans continue to serve as significant points of reference today.

When Panic Moves the Compass Needle

Psychiatry sometimes describes panic attacks as occurring spontaneously, without clear triggers. But I wonder—perhaps the reason we think no cause exists is because we have yet to perceive it. The awkward, dissonant feelings I experienced upon arriving in Austria were, in fact, a longing for sensation born from not knowing—and it was from that moment that panic awakened me.

This sense of disorientation is not exclusive to humans. When artificial intelligence presents us with unexpected images—unsettling or unfamiliar—we, too, feel panic. Hayao Miyazaki, upon seeing a humanoid form powered by AI technology move erratically across the floor, described the scene as “unpleasant.” That reaction reflects a sensory collision for the receiver, but also a response from the creator to a disorder that has lost its direction. And yet, it is precisely in these dissonances and shared discomforts that new narratives and ethical frameworks begin to emerge.

At the jury sessions, I witnessed how jurors, each with distinct senses and languages, calibrated their worlds—pausing before certain works, breathing deeply before difficult questions. Ars Electronica annually invites jurors from across the globe—working across the intersections of technology, art, and society—bringing together perspectives that diverge in cultural background, linguistic identity, and intellectual stance. This diversity transforms the jurors’ bodies into sensory filters—not mere evaluative instruments.

As artists illuminated oblique issues and unearthed micro-histories that had long remained at the margins, the jury process itself unfolded as an alternative language—constructed through lived experiences and collective reflection. Sometimes, works that engaged with novel and radical themes, techniques, or technologies sparked a productive panic among jurors. And the conversations that emerged in efforts to understand the artistic languages at play functioned like magnetic fields, trembling the compass needle toward new directions.

In particular, while listening to the evaluations for the S+T+ARTS Prize and S+T+ARTS Prize Africa, I found myself encountering both the known and unknown in the socio-political contexts of Europe and Africa. Through the pressing questions posed by activist artists and the dialogues they prompted, I came to realize how the affective pulse of panic I had felt when I first set foot on this land had transformed into a compass—guiding me toward an understanding of where I stood in the world. The longer the deliberations went on, the more that initial panic reshaped into curiosity and an initiative to comprehend, a shift mirrored even in the jury room, where daring intersections of topics, methods, and technologies at times stirred a productive kind of panic—an energy that made the compass needle tremble, as if drawn by magnetic forces in search of new directions.

Or, the Syntax of Sensory Conditions

To interrogate the direction that panic takes, we must acknowledge it as a sensation in itself. The body that channels sensation functions as a prelinguistic organ—a site of affective experience. The dominance of a logos-centered paradigm—a rational, utilitarian logic—has, as evidenced by our current global turbulence, reached its limits. Just like the characters in Greek Lessons who approached the world through silence and gaze, what remains when clear language collapses are the residues of sensation, and the body—our prelinguistic sensorium— becomes the cartographer of these scattered feelings.

Responding to this year’s festival prompt, “Panic – yes or no,” I find myself drawn to the space between—to the or. Much like a conditional statement in code—if condition1 or condition2— we must question the condition itself, stretch the syntax, and sometimes dissolve its assumptions altogether. The panic experienced through the submitted works, the jury’s responses, and my own body functions as a living conditional—sensing the world anew, destabilizing datasets, and generating unfamiliar ruptures.

Now, from within a body that trembles with panic, what new conditionals will you begin to write—in a grammar guided by sensation?

Son Hyerim

Son Hyerim is a researcher and curator interested in micro-histories surrounding media environments and the critical or sensorial expansion of perception. Her practice investigates how exhibitions can operate as connective and transformative media—dislocating and recomposing relationships between technological systems and embodied experience. Son holds a Bachelor’s degree in Media Studies and earned her Master of Arts from the University of Leeds (UK), where she developed a curatorial sensibility grounded in cross-disciplinary thinking—navigating between media theory, cultural production, and experimental art practice. At the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA), she has contributed to exhibitions centering on photography and new media. She is also actively involved in international exchange projects, where she explores the potential of exhibition formats as sites for translocal dialogue and curatorial experimentation. She also engages in art writing and criticism, and in 2024, was selected for Pitching, a program recognizing emerging contemporary art critics