This year’s Golden Nica in the category “Digital Musics & Sound Art” goes to media artist Navid Navab and Garnet Willis for their project “Organism.”

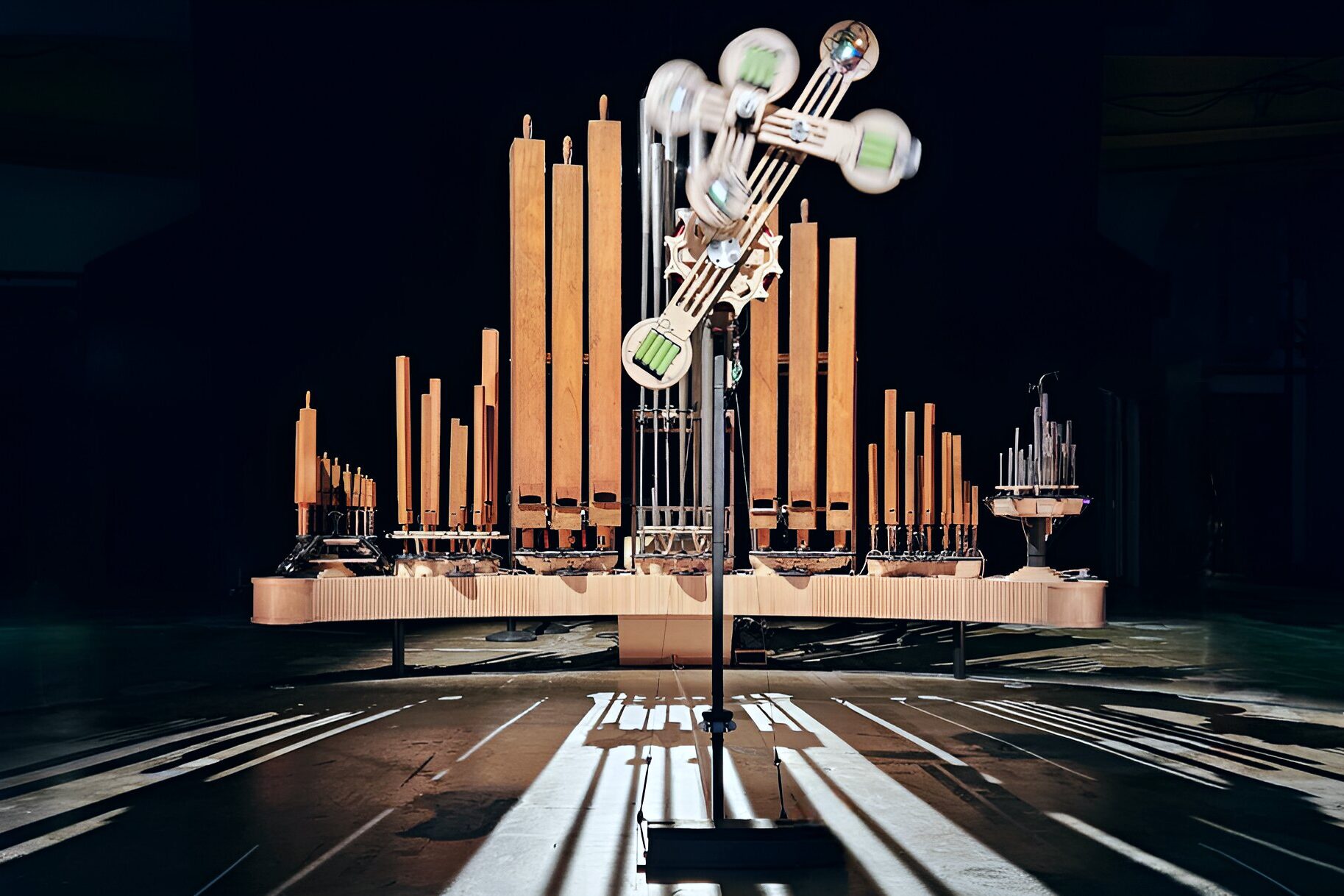

Anyone who was in the POSTCITY bunker during last year’s Ars Electronica Festival may remember that moment. The humming in your chest, the rattling of the technology, the archaic sound creeping through the concrete. “Organism” by Navid Navab and Garnet Willis was no ordinary piece of music. It was an experience, raw, expansive, almost eerie. And above all: difficult to forget. No wonder, then, that the work has now been awarded the Golden Nica in the “Digital Musics & Sound Art” category.

This category is one of the most traditional at the Prix Ars Electronica. Ars Electronica introduced the category for computer music back in 1987—a bold move long before electronic sounds were commonplace in the art world. Since then, the field has developed rapidly: from algorithmically generated music and hybrid compositions to immersive soundscapes that challenge and expand our listening habits.

But what makes “Organism” so special? And what role does chaos play in a work that seems so precisely programmed? In conversation with Navid Navab, we dive into a world where machines breathe, organ pipes whisper, and order is just an illusion.

What drew you to the 1910 Casavant pipe organ, and what does rescuing this instrument from gentrification mean to you artistically and politically?

Navid Navab: Much of my work is media-archaeological in nature, often revisiting technologies of the past to suggest different futures through their critical rethinking. I had no initial plans to work with pipe organs. I was invited to activate a heritage site — one of the oldest churches in Montreal — as a way of opening its geopolitical history to new becomings.

However, the site underwent rapid gentrification. Out of curiosity, I climbed into the organ: a four-story structure full of rooms, nooks, and ladders. I began documenting its abandoned state — a heritage instrument left to dust and entropy, damaged by renovation projects and neglected in the indifference of real estate development.

Rather than seeing this encounter as incidental, I took it as an invitation to media-archeologically investigate the organ as a complex socio-historical site — one in which culture had managed to bend turbulent materiality to its will. By media archaeology, I mean a practice of tracing the socio-historical roots of contemporary technologies — in this case, technologies of sonic formation — in order to expose their overlooked material conditions and cultural contexts, and to suggest new pathways for innovation based on those often subtle, forgotten aspects.

From this historically informed investigative lens, the pipe organ represents, to me, a symbol of civilization’s triumph over nature’s turbulence — a machine that tames the lively aerodynamics of sonic invention in order to impose human ideologies, such as the 12-tone system. This is different than criticism. Of course I enjoy traditional pipe organs as complex socio-energetic sites where culturally formed notions of harmony, beauty, and complexity are expressed. But I also draw attention to how these idealizations have replaced our relationship with nature’s generative wildness — with its capacity to invent forms that do not necessarily adhere to the ideals of Western tonality.

My investigations into airflow quickly led to surprising — at times nearly unpredictable — sonic results. These early experiments marked, for me, a re-discovery of the organ: not as a relic of controlled tonal stability, but as an instrument capable of expressing turbulent patterns of formation with nuance and complexity, if only its dormant materiality could be liberated from the strictures of cultural control over airflow and pitch. That became the investigative theme of the work. I was soon joined by Garnet Willis, an expert in instrument making, and together we dove deeper into the previously repressed belly of the instrument — treating it as a technological site where nature’s wildness had long been converted into predictable sonic culture.

Our goal became clear: to set this process — the becoming-cultural-of-nature — free. To open it to perpetual renewal and transformation. To listen, to learn from, and to co-create with the generatively of nature, instead of seeking to conquer it.

No digital sounds are used in the performance — what were the challenges or opportunities of working solely with mechanical and acoustic means?

Navid Navab: Working via the aerodynamics of sonic formation within pipe organs presented me with several surprising opportunities in my career-long quest (ie. as in Aquaphoneia) for imagining a post-schizophonic world, where the computational properties of matter would allow us to avoid separating sonic events from their sources, as digital mediations do.

In my investigative quest to reawaken the turbulent materiality of the pipe organ — and in search of the source of its agency or its form of liveliness — I discovered several fascinating energetic phenomena, such as vortex-shedding and edge-tone jumping, which, to my surprise, remain the subject of scientific controversy to this day.

Let’s briefly discuss them. When the incoming laminar flow (of air) meets the edge of a flute or pipe organ, it curves unto itself, vortices form (like a perpetually shape-shifting stream of whirlpools), and an unstable form of order arises from the coming together of laminar flow, turbulent flow, and shed vortices — a dynamic unity, like the emergence of a consciousness greater than the sum of its parts. The frequency of the shed vortices leads to the emergence of hundreds of frequencies, some faint and some slightly louder. This is oscillating flow is called vortex-shedding — the phenomenon responsible for the eerie sound of Aeolian harps, for example.

Then the upper body of the flute — which is essentially a resonator — acts as a curator for the shed vortices. Traditional organs provide a stable and calculated flow (ie. air pressure, volume, velocity) to ensure that the most prominent frequency of the shed vortices matches the resonance of the flute’s body. In this way, a stable tone (or note) is born, maintained, and hyper-stabilized. The potential agency — or lifelines — of the pipe’s energetic regime is damped and made dormant in service of the organ designer’s need to adhere to the necessary predictability of the Western 12-tone ideology. In Organism, all of this — the sexy flux of matter, and the pipe’s energetic liveliness — has been freed and centralized.

Another fascinating discovery, for me, was that of “edge-tone jumping”. When a pipe’s incoming air (its energetic excitation) is varied, at certain energetic thresholds the vortices may suddenly, spontaneously, and discontinuously give birth to another colony of vortices — and hold them, or enfold them! In the physics of dissipative structures and nonlinear dynamical systems, discontinuous jumps in organization or temporal-forms are signature of phase-shifting, and within the pipe they correlate with a discontinuous jump in pitch/timbre/loudness. Musically, this is what causes a reed instrument to “yodel,” jumping up or down — often by intervals of octaves and sevenths.

As an art-science-composer, I saw Organism as an opportunity to further explore these fascinating phenomena. In concerts, I configure the energetic regime of Organism — in terms of its ecological air pressure distribution and modulatable thresholds — into such a state that the slightest variation of air results in edge-tone jumping across a curated number of pipes that have been placed into energetic compatibility and this dialogue with one another. Unlike traditional organs that provide a stable and isolated air-fllow to each pipe, here, when one pipe sings, it pushes and pulls on the swirling of vortices of another, potentially causing it to edge-tone jump. Now imagine this times sixty pipes — they form an ecology of interdependent timbres. Each configured ecology is a metastable environment, a structured-improvisation for phase-shifting vortices, and as a composer-performer, during concerts, I musically surf upon their turbulent waves.

The challenge is not only technological but also mental: I have to give up my desire for 1-to-1 control over sound and instead listen deeply, as one would when encountering a riverbed. Then, after befriending each riverbeds dynamic flow — Organism’s various metastable Comprovisational environments — I may begin to modulate thresholds of flow to guide them, surf upon them, swim within them, percussively splash around, etc. It is a completely different mode of musicking, based on collaborative exchange of energy, via the gesturally guided robotics of Organism. Technologically, the challenge was achieving robotic modulations capable of meeting these turbulent formations at their fast and cascading levels of temporality. That is why multiple prototypes were needed across many years (2016-2024). Organism’s ultra-fast servo motors and actuators are able to modulate these thresholds quickly enough to allow sonic affordances often associated with digital musical cultures — such as microsound, timbrally rich attack-sustain-release envelopes, complex modular-synth patching, etc.

How do you see the role of unpredictability in your work — is it something you embrace, steer, or enter into dialogue with?

Navid Navab: Unpredictability, uncertainty, and indeterminacy are topics many composers and thinkers have engaged with throughout history. In my practice, I move beyond the aestheticization or sensationalization of indeterminacy as an abstract concept to be admired merely for its surprising outcomes. I am interested in life — the generativity of the movement of life, and of liveliness itself. Of course, whenever something exhibits a degree of liveliness, intentionality, and generativity, a correlated degree of indeterminacy is inevitable.

For me, unpredictability is not something to embrace blindly or to conquer, but rather something to remain in perpetual dialogue with — energetically, and ethico-aesthetically. More specifically, I am interested in developing new techniques and methodologies for collaborating with the lively and excitable forces of nature — forces we ourselves are an expression of. This way of thinking invites us to move beyond the alive/not-alive binary and instead to consider liveliness as a matter of degree, not kind.

So what is liveliness? An energetic system in tension with itself — from whirlpools to chaotic pendulums, turbulent formations, and metabolic systems — develops intensity, inner time, intentionality, and a generative sense of liveliness. The more something is lively, the more indeterminate it appears from the outside, because, like people, it has developed internal dynamics and tensions that it can resolve internally, without relying on the deterministic rules and linear causality of the outside world — of positive science.

Intentionality, then, is the sense of directionality that a system develops as it resolves its energetic tensions in response to excitations, and in dialogue with the energetic milieu in which it is embedded. When it does this, it generates new forms — it invents something. This is nature’s creative engine, and it is something artists, scientists, and ecologists alike can engage with. Again: we ourselves are expressions of this sort of happening.

Intentionality — whether biological, ecological, political, or otherwise — can be seen as the formation of directionality within a dynamic unity.

With Organism, what I developed, methodologically and compositionally, is a platform that brings various forms of intentionality (more-than-human creativity) into curated resonance — or transductive dialogue — with one another, in ways that expose, honour, and preserve their degrees of liveliness. In immediate vibrational relation, these generative forces are enticed to communicate and negotiate their creative intensities, co-creating turbulent-sonic worlds. Of course, in performance, I myself am one of these unpredictable forces, in dialogue with Organism’s metastable energetic regime and its turbulent formations.

This way of writing music required a new paradigm — one based in energetic negotiation with the movement of life. I treated Organism’s turbulent materiality — its ecological, machinic, energetic, and material agencies — as fellow co-creators on a deep-listening stage. I relied on techniques developed over decades of collaborative creation with improvising musicians and dancers. Thinking alongside the likes of Gilbert Simondon and Ilya Prigogine, I grounded myself in the relational realness of energetics and the thermodynamics of nonhuman intentionality, where liveliness emerges through gaps of indeterminacy.

I then transposed techniques of inter-cultural Comprovisation — a balancing of deterministic cultures of composition against the indeterminate thrust of improvisation — which I had learned from working alongside composer-performers such as Sandeep Bhagwati, George Lewis, and Lori Freedman, into new techniques for intra-agential Comprovisation. This placed improvisatory or generative forces — from human to technological to material — into curated dialogue with one another.

In my approach, composition and creation become acts of curation — or a giving-voice-to — events of formation and forms of mattering: a perpetual negotiation of modes of co-existence, and of modes of coming together between multiple identities. By identity, I do not mean a fixed position on a rigid grid, as in classical identity politics, but dynamic events of mattering — intensive zones of individuation where dimensions of time fold into one another to develop an embedded sense of creativity, of ever-emergent collective intentionality. As mentioned, my approach stems from phenomenologically-informed investigations into how liveliness, as a matter of degree, emerges through energetic formations.

Dialogue, negotiation — of what matters — is politics. Negotiation is curation; curation is politics. Everything matters, at every instance. And at every instance, the things that matter are renewed and must be incorporated. Therefore, having a vision and a methodology for perpetually negotiating and preserving what matters is crucial.

Giving up the desire to conquer nature’s wildness — and instead entering into dialogue with it — is not only an aesthetic choice. It is a political, ethical, and methodological one. We must bypass the military-cybernetic complex upon which today’s digital tools and idealizations of nature — from generative algorithms to AI — are often based. Composition, curation, and politics converge in the need to develop integrative methodologies for honouring life — the movement-of-life — and its diverse forms of intentionality. A perpetual dialogue with unpredictable yet generative forces is essential if we are to escape the trap of reshaping the world only in our own image — treating it as a canvas for our wants and projections. Instead, we might embrace how we ourselves emerge from, are moved by, and move within the world, while ethically engaging with the collective power and creativity that world offers.

Chaos and turbulence show us this: that lively and generative forces possess directional tendencies, that every little thing matters — and matters on — at every instance. And at every instance, new elements and forces appear that did not exist a moment ago. These must be considered, enfolded, and responded to. In fact, chaotic and turbulent systems — and their cascading temporalities — already do this perpetual enfolding for us.

The project touches on chaos, emergence, and interdependence — ideas common in both physics and ecology. What do you hope people take away from experiencing those ideas in sound?

Navid Navab: We live in turbulent times, where change unfolds rapidly, and where even the smallest causes can ripple outward — across personal, political, and ecological scales. In such a world, developing an attunement to principles of chaotic wholeness, interdependence, and their excitable creativity offers a more artful, embodied way of co-existing with the generative forces that inform us.

As an investigative ArtScience platform, Organism + Excitable Chaos explores nature’s form-giving tendencies in order to imagine integrative modalities of technological collaboration with nature’s wildness. For example, the excitable generatively of chaos and inner liveliness, as revealed in this work, emerges not from disorder but from internal resonances — correlations between the “parts” of a moving ensemble and the “whole” — producing a dynamic flow of formation. Organism sonifies these movements of coming together and falling apart, transforming them into organismic soundscapes for sensorial engagement and critical reflection.

Wherever things come together and fall apart — to become and unbecome whole — time is lived and felt in a unique way — this inner liveliness is not fully reducible to a physical principle or law. It may be partially described thermodynamically as a reservoir of indeterminacy — a storage of potential that produces directionality, sensitivity, inner intensity, and emergent intentionality. These are nature’s theatres of invention.

One can feel, even in the faintest oscillating patterning of turbulent and chaotic flow, a degree of liveliness. Excitable Chao’s mode of liveliness and inner time, while not fully quantifiable through positive science, can be partially felt through sound, via its sonification by Organism.

When we seek to conquer, control, or precisely shape the wildness of nature — the liveliness of formation itself — we risk suppressing that inner vitality in order to inscribe our own ideas upon it. This is a dance we must learn to perceive. We should thermodynamically, energetically, and socio-politically locate sites of liveliness within formation events — and begin to study which transformations are liveliness-preserving, exciting, and varied, and which are liveliness-destroying, producing only purity, stasis, and extreme stability or death.

This calls for an ethos and a techne — a way of knowing and a way of doing — in response to the conditions we are embedded in. From ecocide to genocide, we are now entangled in networks of relation structured by exploitation, domination, and capital gain — systems of agential slavery that reduce life to function.

My work does not take up these complexities in a direct political register. But my life-long search is devoted to finding alternative ways of sensing, preserving, and co-existing with life — with liveliness — with the generative wildness of nature.

As a composer-performer, the deeper aim is to rethink technology as the connective tissue between nature and culture — to reimagine the dynamics of performance technologies that we often take for granted. The quest becomes one of generating life-preserving methodologies — moving away from technologies of representation and toward systems of energetic exchange and mutual becoming.

There is urgency, yes. But at the scale I am immersed in, there is no room for panic. The task is slow, iterative, collaborative, and experimental. It is perpetual. It means staying with the trouble — of co-expressing, co-deciding, co-negotiating what should matter at every instance. This is a politics enacted at the level of energy, where non-idealized forms of liveliness can thrive.

And so, every performance is a new struggle — a new encounter. To place forces into communication with one another. To allow something alive to come forth. To curate not what note to play, but which forces and exchanges are potent sites of expression, worth preserving, channeling, and surfing upon.

Our generative algorithms are idealizations of nature — abstractions built on the military-cybernetic logics of prediction and control. The more difficult, and necessary, work is to ask: how can we engage with forces we neither fully understand nor control?

We, too, are nature expressing itself. And when we observe how we miscommunicate and mistreat one another, it becomes clear that we are not yet skilled at this task.

So my approach is to return — to the faintest, yet most unruly forms of life: chaos, turbulence, and intensive temporalities — where matter begins to thermodynamically accumulate its reservoirs of indeterminacy. To the places where liveliness begins again.

What has surprised you most during the development or performance of Organism — either in the sound, the system’s behavior, or audience reactions?

Navid Navab: I developed Organism with a public engagement methodology through a series of experimental soft premieres. Since one of my goals is to communicate complex topics with publics, I remain deeply interested in audience experience. There were numerous fascinating surprises. Let me share a few.

After performances, audience members sometimes approach me to recount their experiences — often describing having been transported to specific musical cultures and sonic tableaus, ranging from ritualistic Gagaku music, polyrhythmic Brazilian percussion, Ney (Sufi end-blown flutes), Amazonian and deep forest swamps, post-rock, modular synth music, microsound, glitch, and more. I write these accounts down and keep track of them. At first, they were genuinely surprising to me, as I never intended to reference any specific musicking culture. In both my performances and my development process, I enter a deep listening state to engage with the energetic thresholds of Organism and to musically surf its turbulent dynamics. I never compose with pre-existing forms — whether from myself or a score. Instead, I modulate energetic thresholds via gesturally controlled robotics that shape the flow of air.

So how, then, are such culturally specific sonic references perceived by audiences? Upon reflection, these early responses reaffirmed my conceptual approach: it meant that I was opening the aerodynamics of sonic formation — previously confined by the 12-tone system — to a state of perpetual becoming-cultural-of-nature. By opening this process to ongoing renewal, live on stage, sonic cultures were allowed to emerge through the audience’s in-situ experience of the complex material-social-sonic event, rather than being imposed by me. This, I’ve been told, creates an opportunity for deep listening and imaginative engagement.

As the composer, I can say that — in terms of its energetic methodologies — the music of Organism is culture-agnostic. And yet, people have said they were transported to the Amazon, to South American rivers, and so on. How could that be?

Well, control over turbulence is the very technological process involved in the becoming-cultural-of-nature. Cultures and societies have developed their own signature ways of shaping turbulence into timbre, tone, and song. Organism opens this process up — it frees the dynamics from fixed ideology and co-steers them energetically into organismic soundscapes, allowing for the emergence of sonic cultures and ecological textures. Each texture is a curated negotiation between energetic sites of activity and their interdependent formational tendencies.

Another, very different surprise came from hearing that some audience members disliked — even “hated” — the sonic palette of Organism with a degree of passion and certitude that was itself fascinating. How is it that, in the same concert, Organism’s turbulent breath could be experienced as comfortably transportive and expansive for some, and brutally “off” or indigestible for others?

Upon further investigation, I noticed that those who rushed to categorize the music within a binary of good versus bad often remained at the back of the hall and were less engaged with the adventurous materiality of the unfolding event. After all, improvisation within uncharted territory requires both performer and audience to remain present — to discover something together about the nature of what is unfolding. This led me to introduce more perceptual framing into my gestural-sonic mise-en-music. I’ve found that a willingness on the part of the audience to engage with the tonal strangeness of Organism is a key factor. My non-sensationalized interactions with the pipes’ energetics now serve as a kind of guided attunement — a sound walk through Organism’s shifting ecologies of sonic formation, helping to perceptually ground the sonic events in their material origins.

But still, something else is often at work in these responses — something deeper, perhaps. Organs are historically designed to ritualistically hail the triumph of civilization over the unruly turbulence of nature. They highlight how we, cultured humans, have colonized the wind according to principles of harmony, beauty, and order. Organism’s sonic palette, by contrast, refuses these “far-too-musical” notions — it does not foreground melody over its noisy material substrate. Like the cascading vortices hidden in the dissipation of smoke, Organism’s timbral smoke is messy, subtly alive, granular, unpredictable, “off-tune,” and emotionally charged in a strangely nonhuman way.

And so, like the smoke, the dissipative musicality of Organism can remain obscure — especially to ears not engaged with its cascading, noise-enfolding, or psychedelic temporality.

You’ll return to the Ars Electronica Festival this year after presenting your work in 2024. How has your practice evolved since then, and did your last experience at the festival influence Organism in any way — conceptually or technically?

Navid Navab: Organism grows, and so does my relationship with it. In fact, as an investigative platform, it was designed from the outset to allow for perpetual growth. As Leonardo da Vinci once said, “Art is never finished, only abandoned.” I foresee remaining committed to Organism’s ongoing, situationally embedded evolution.

Since last year, beyond various refinements to its electromechanical and software systems, the most meaningful transformation has been the deepening of my relation to the instrument itself. I’ve come to understand more intricately the non-linear behavior of each pipe and its energetic regime — learning how to channel each one’s degree of liveliness and how to place it into resonant relation with others. Through this, I’ve developed new and emergent musical cultures and energetic environments, which I’ve continued to explore, modulate, and navigate more intuitively over time.

This has led to the emergence of many new sound works — each rooted in the specificity of that evolving relation — and I’m excited to perform within these newly formed ecologies. As a result, each performance remains completely unique, while the musical culture of Organism continues to deepen and complexify through lived experience.

In this way, Organism is less a fixed artwork than an ongoing co-evolution — an interface for mutual learning between artist, machine, matter, and the more-than-human dynamics of musicking.

The Organism project will be on display as part of the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz from September 3 to 7, 2025, at the Mariendom. You can find more program highlights here.

Navid Navab

Navid Navab is recognized as a media-alchemist and anti-disciplinary composer with a background in biomedical sonification. Navab’s work illuminates the intersection of investigative arts, media archeology, and philosophical biology and is characterized by sculpturous engagement with transductive structures of liveliness. His recent creations orchestrate sensory attunement to the dissipative formations and uncanny forms of order that flow from machinic engagement with excitable dynamics of matter.