What’s holding back climate protection?

The toolbox for effective climate protection is ready and waiting. We have long known which adjustments need to be made: expanding renewable energies, electrification, expanding public transport, increasing efficiency in industry, replacing oil and gas heating systems — and much more besides. Nonetheless, the necessary political and economic decisions for this to happen are often delayed while the situation gets worse. In short: climate protection is being postponed.

We have all heard it before: “Actually, China has to start, Austria can’t contribute that much.” The advantages of climate protection and the historical responsibility are usually concealed in this way. “Too much climate protection, and the economy will drift away.” The fact that greening the economy in fact increases competitiveness and generates jobs goes unmentioned. “One day, cars will drive with eFuels in the tank anyway.” Yet eFuels in the tank are inefficient and expensive.

There are many sides to such delaying tactics. Those who use them do not deny the climate crisis. Instead, responsibility for climate protection is shifted to other levels, supposed disadvantages of climate protection are brought to the fore or — often technical — false solutions are presented. What these delaying tactics have in common is that they reinforce existing uncertainties, but also legitimate concerns about the climate crisis, mixing them up with disinformation.

The climate policy debate is changing also in Austria: The existence of the climate crisis or climate science findings are currently less in focus, with the discussion rather around specific measures, laws, or targets. While some stakeholders are calling for more climate protection and faster action, here, too, others are putting off specific decisions and measures.

The danger of delaying tactics is that they are difficult to recognize. Even if only some people use them consciously, the arguments are unconsciously adopted by many. As a result, positions in the climate policy debate become entrenched, with hardly anyone prepared to make tangible decisions. The implementation of measures comes to a standstill and restructuring is prevented. For a return to a constructive debate and progress on climate policy, we need to recognize and refute delaying tactics — or prevent them. After all, the most effective approach is when they cannot become established in the climate policy debate in the first place.

Read more:

KONTEXT-Analyse: Wie Klimaschutz verschleppt wird

https://kontext-institut.at/inhalte/verschleppung-klimaschutz-konklusio/

KONTEXT-Analyse: Klimadiskurs-Monitoring 2025

https://kontext-institut.at/inhalte/klimadiskurs-monitoring-2025/

Is technology the cure-all for this?

We already have most of the technologies needed to reduce emissions: wind power and photovoltaics, batteries, heat pumps and electric vehicles. These must be expanded and used wherever they can replace oil, coal, and gas, so as to advance the transformation as rapidly as possible.

Politically and economically, however, technologies are often promoted that are not yet ready for the market or are only suitable for niches. Their potential applications are thus greatly exaggerated. Technological misconceptions of this kind lead to a delay in the expansion of tried and tested technologies that are ready for use. The result is that oil, gas, and coal remain in use. This can be seen, for example, in the debates around combustion engines and heating.

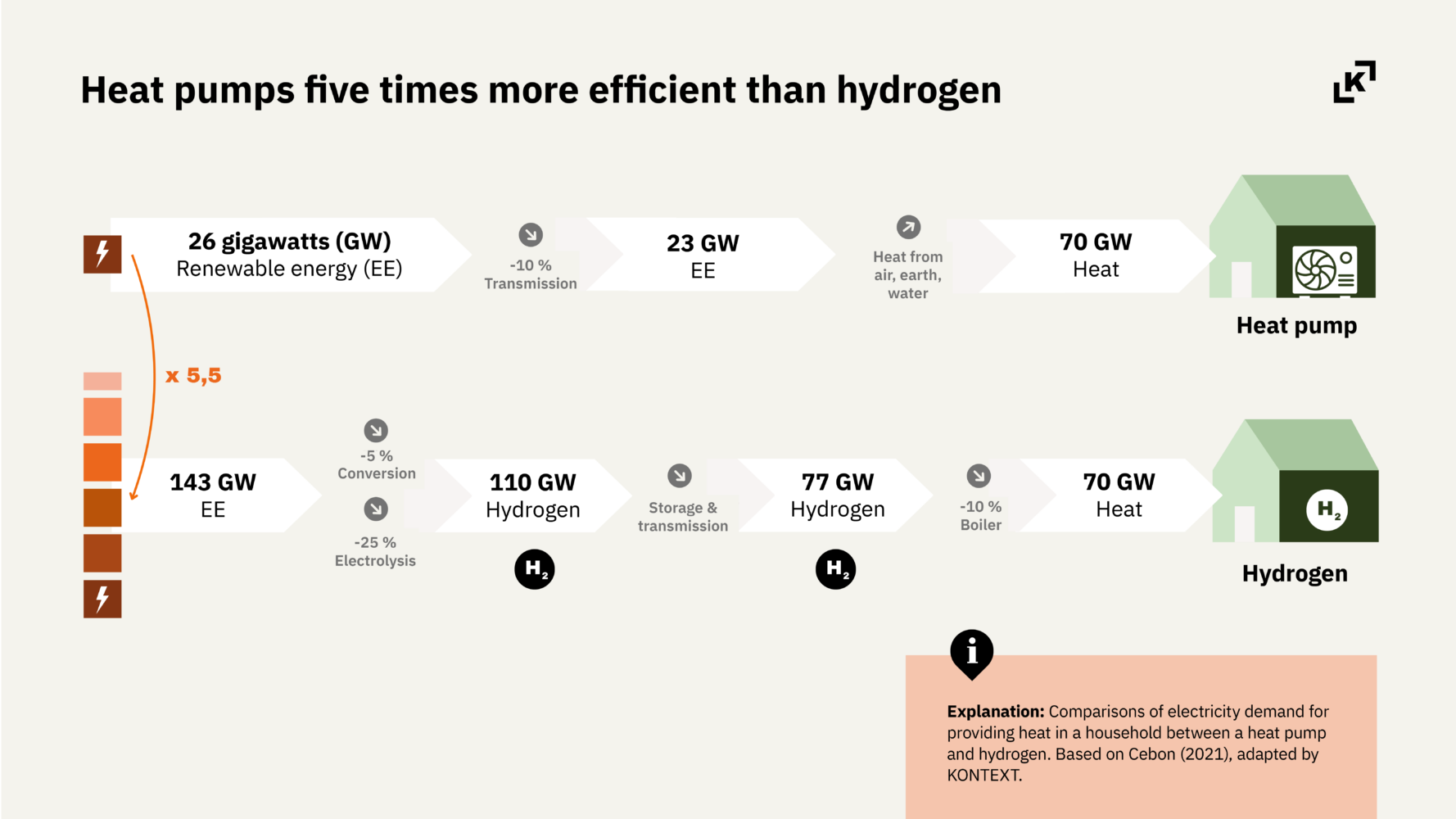

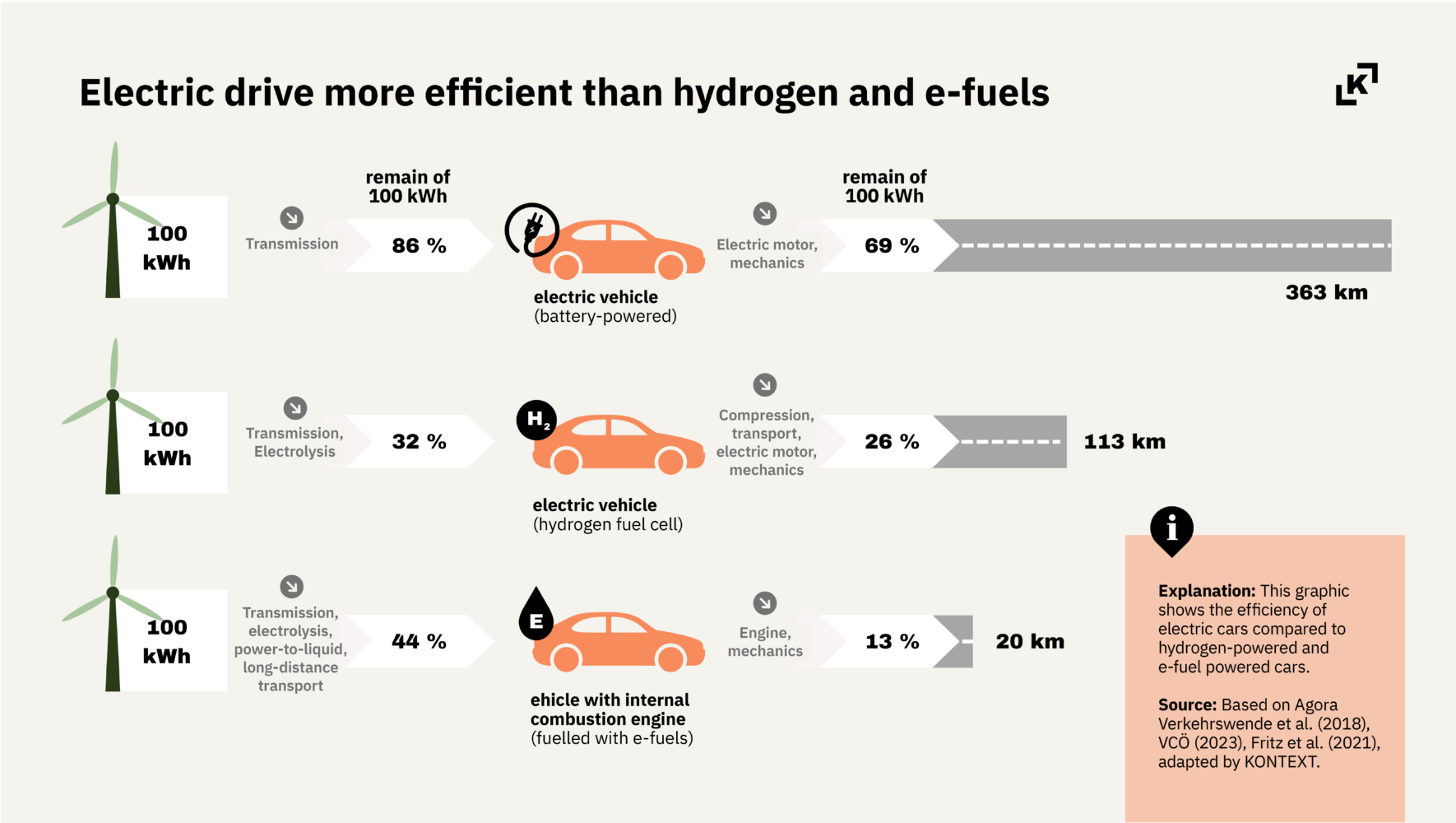

If it is promised, for example, that green gas will one day flow through the heating pipes, the heating system will not be replaced. Yet heat pumps are five times more efficient than heating with hydrogen. If it is suggested that combustion engines should also be fueled with eFuels, the switch to electric and public mobility will be slowed down. However, the use of eFuels for cars is in fact inefficient: only around 13 percent of the energy supplied can be used for driving. With an electric car, on the other hand, it is more than two thirds. Moreover, eFuels and hydrogen cost more than their respective sustainable alternatives.

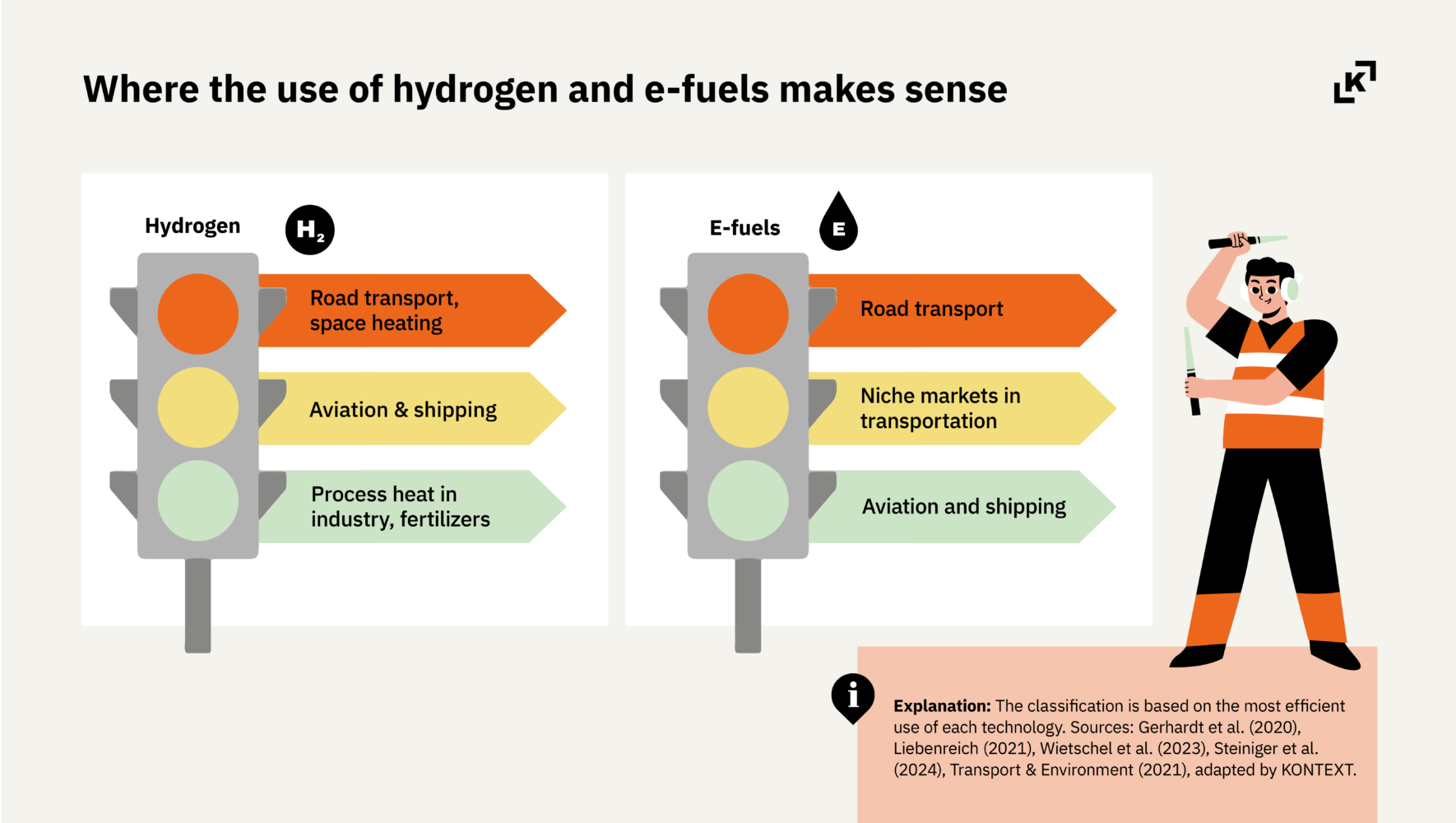

There are certainly areas in which hydrogen and eFuels are concrete solutions, not mirages. This is the case especially when reliable alternatives are in short supply, in aviation and shipping, for example, or industry. However, if the fuels are employed in inefficient areas such as heating or transporting individuals, this deprives industrial companies of available resources — and thus the only pathway to making their production processes climate-neutral.

So the efficient use of technologies requires technological clarity. Key here is to differentiate and be guided by the scientific consensus. Those technologies that are market-ready and suitable for widespread use, such as renewable energies, heat pumps and electromobility, need a legal basis and investment in order to expand and scale them up now. Many other technologies are ready for use, but are not appropriate in all applications (eFuels and hydrogen). The resources for their production are limited in availability, while the manufacturing processes are often costly and come with energy losses. They should therefore be used in a focused manner where no alternatives currently exist. In addition, research and development is needed to be able to consider in future such technologies as are still in their infancy today, or do not even exist as yet. To ensure optimal efficiency in the use of the renewable energy produced, it is imperative to reduce overall energy consumption and take appropriate supporting measures: renovating buildings and expanding low-cost public transport in mobility are essential for this.

Read more: KONTEXT-Analyse Mit Technologieklarheit gegen Trugbilder https://kontext-institut.at/inhalte/konklusio-technologieklarheit/

Can climate protection be speeded up?

We’re late, the house is on fire. But the good news is that we’re not too late. Every fire extinguisher prevents the fire from spreading further, every firewall protects us from burns. With everything we do now to combat the climate crisis, we are preventing it from getting worse, containing its impact, and enabling a future worth living. But how do we get out of deadlocked positions and enter constructive dialog. And most importantly, take action?

The scientific community has long been in agreement on many climate policy measures — something that needs to be stressed. Take eFuels, for example. They are too expensive and inefficient to produce and at the same time not available in sufficient quantities to cover supply in all sectors. So while they are unsuitable for a car’s tank, they are needed where no other options exist.

Scientific consensus can only form the basis for a debate on climate policy, however. It is also important to address legitimate concerns surrounding the climate crisis, as well as hopes. The consequences of the climate crisis and the sheer scale of what needs to be done are frightening. If this fear leads to paralysis, denial or panic, consistent, swift action becomes impossible. To prevent this from happening, we need a vision of the future we can build that contains effective climate protection. With a positive outlook, every building block is easier to put in place — no matter how enormous it may be.

We must also be aware that no one perfect solution exists. We can only accomplish the major transformation towards a climate-friendly society and economy if we turn many screws at the same time, pull different levers: a clear political framework, for instance, the necessary infrastructure, investments, or taxes to finance them. Only the combination of different building blocks will propel the transformation forward. The distribution of responsibility, social justice, and the opportunities and limits that solutions entail, should also be factored into the planning of measures. It is vital, too, to highlight all the benefits that climate protection brings to society. Rather than drawing attention to the negative aspects of climate protection and fueling doubts about its feasibility, it can be shown it is not only necessary, but feasible as well. Overcoming the climate crisis is not only a necessity, also a great opportunity.

Things can then happen rapidly. At so-called tipping points, far-reaching changes occur in a short space of time. The climate crisis threatens to accelerate at negative tipping points: if large masses of ice melt, for example, the situation rapidly and drastically worsens. In society, however, positive tipping points can set in motion the necessary dynamics for rapid action. The critical mass that needs convincing of a change in society for it to occur is small. Once it has been reached, even small tweaks and minor levers can have major impact at the right time.