In 1954, Italian publisher Giulio Einaudi Editore released an anthology of farewell letters written by individuals who were persecuted, tortured, and executed by the Nazis and the Wehrmacht during the Second World War. Among them were women and men—and in some cases, even young people and children. The foreword was written by Thomas Mann, who wrote:

“It keeps returning, and the heart tightens at the thought of what became of the ‘victory of the future,’ of the faith and hope of that youth, and of the world we now live in. A world of malignant regression, where superstitious and persecutory hatred is coupled with panicked fear; a world whose intellectual and moral inaccessibility has been entrusted with weapons of destruction of horrifying speed—stockpiled under the idiotic threat of ‘if need be,’ threatening to turn the Earth into a wasteland shrouded in poisonous vapors. The decline of cultural standards, the withering of education, the apathy in the face of atrocities committed by a politicized judiciary, fat-catism, blind greed for profit, the collapse of trust and integrity—produced, or at least encouraged, by two world wars—offer poor protection against the outbreak of a third, which would mean the end of civilization.” (Thomas Mann)

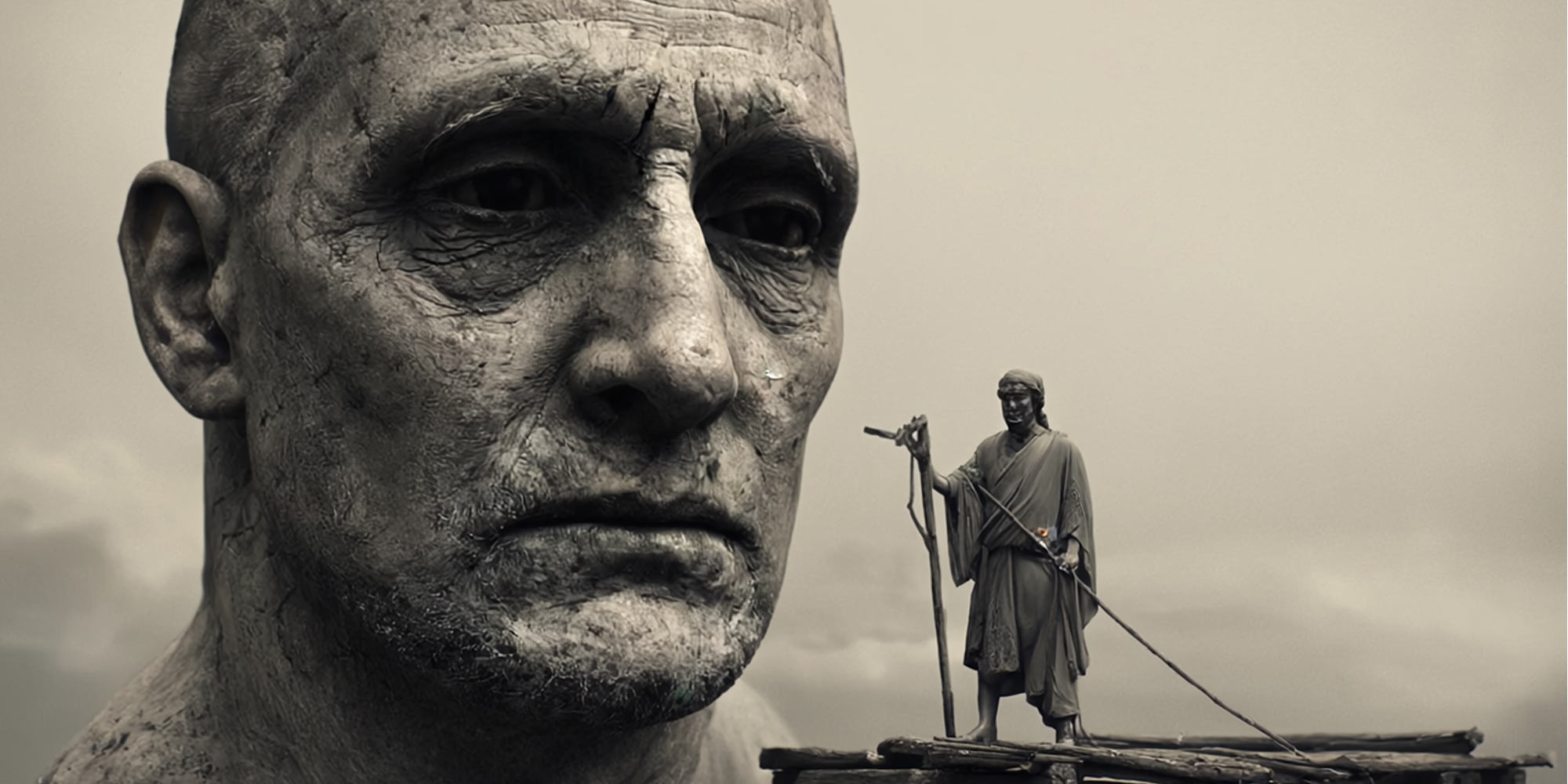

This warning against the recurring threat of a “world of malignant regression” sets the tone for the Big Concert Night of Ars Electronica 2025. In response to today’s global crises—and in commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War—the evening presents a new production of the opera The Emperor of Atlantis (orig. Der Kaiser von Atlantis) by Viktor Ullmann and Peter Kien.

This chamber opera, fully titled The Emperor of Atlantis or Death’s Refusal (titled originally Death Abdicates), was composed in 1943/44 by Ullmann and Kien in the Terezín (then called Theresienstadt) ghetto/concentration camp. Both artists were deported to Oświęcim (Auschwitz) in 1945 and murdered there.

It remains uncertain when Ullmann began composing the opera or how much of the libretto he originally wrote himself. The painter and writer Peter Kien was only brought into the project after the score had already been completed. The final page of the 140-page manuscript is dated November 8, 1943, and Ullmann credited Kien as the librettist on the title page.

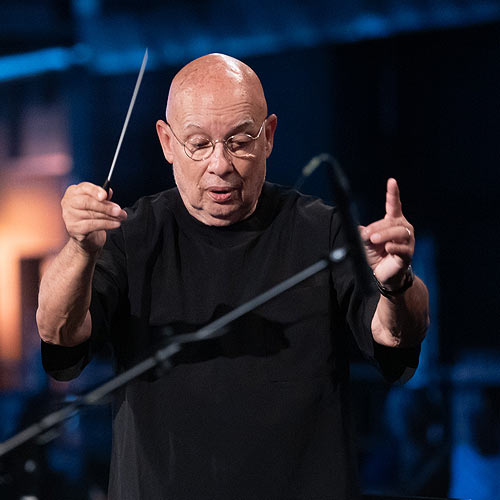

Rehearsals began in the summer of 1944, with set and costume designs by Kien. But the premiere never took place—partly due to reported disagreements between the composer and the production team, and partly out of fear, well-founded, that the SS would recognize the obvious allusions and retaliate accordingly. The autograph score—written on the backs of prisoner forms and deportation lists—made its way out of Terezín. However, it was not until 1975 that the work was performed for the first time, in an arrangement by Kerry Woodward in Amsterdam. The first performance in Germany took place in 1985 in Stuttgart, conducted by Dennis Russell Davies, who also serves as the musical director of our current production. It was 51 years after rehearsals first began—in 1995—that the opera was finally performed in Terezín.

The Prolog

The quoted foreword by Thomas Mann introduces the program’s prolog, in which Chamber Music No. 1 (1922) by Paul Hindemith evokes the period before the Second World War and the early rise of fascism. This theme is also reflected in the sound installation Proklamation (Proclamation) by Julian Pixel Schmiederer, created specifically for the entrance area of the Train Hall. The work addresses the media propaganda of the 1930s, drawing a direct connection to the threats we face today.

Between the movements of Chamber Music No. 1, excerpts from the 1954 collection Farewell Letters from Those Sentenced to Death are read aloud. The project #eachnamematters is also dedicated to honoring the victims of National Socialism. Since 2021, this annual initiative—organized by the Mauthausen Memorial and Ars Electronica—has been presented at various locations, projecting the names of over 82,000 people murdered in the Mauthausen concentration camps. So far, the project has been displayed on the outer walls of the Mauthausen camp, at the Gusen crematorium memorial, at the entrance to the “Bergkristall” tunnel complex, and on the facades of two “Brückenkopf buildings” in Linz, both constructed during the Nazi era.

The Opera

The train hall of POSTCITY—Ars Electronica’s main venue since 2015—is a stage charged with profound symbolism for this evening. On the one hand, there is the monumental concrete structure of the former postal sorting center, opened in 1992 and outfitted with a massive nuclear bunker, which was already decommissioned by 2015—partly due to the rapid rise of online commerce.

On the other hand, the hall’s close proximity to the train station and the four railway tracks leading directly into this transformed performance space inevitably conjure associations with the unimaginable scale of industrialized mass murder during the Holocaust and the Second World War.

This “total war against humanity and human dignity” is at the heart of Ullmann and Kien’s operatic parable, which profoundly reflects the horrific realities faced by those deported to Theresienstadt. In doing so, it not only condemns the brutal Nazi regime but also serves as a timeless testament against tyranny and oppression.

The Emperor Overall of Atlantis rules as a tyrant over his land and proclaims a total war of everyone against everyone. Death, outraged by this arrogance, feels robbed of his duty and refuses to comply—he goes on strike and abdicates.

As a result, no one can die anymore: soldiers cannot kill each other, those sentenced to death do not die, and the country descends into chaos. Without the threat of death, the emperor loses his power. Desperate, he begs Death to resume his work. Death agrees but on the condition that the emperor must be the first to follow him. The emperor accepts and bids farewell to life with a grand aria. This restores the balance of life.

Characters such as “the Loudspeaker” and “the Drummer, not quite a real figure. Like the radio“, reflect the propaganda and manipulation machine perfectly orchestrated by the Nazis. The philosophical dialogue between Death and Harlequin raises the question of the meaning of life—”life that can no longer laugh and death that can no longer weep.” And, of course, there is a love story: a soldier and a young woman choose love over killing.

Composed under the harshest conditions—amid the deprivation, fear, and horrors of the Terezín ghetto, and in the constant awareness of possible deportation to a death camp—The Emperor of Atlantis is a powerful example of artistic resistance and creative resilience. But this opera deserves recognition not only because of the extraordinary circumstances in which it was created, but also for its artistic depth and lasting value beyond its historical context. In this work, Ullmann wove together elements of popular music of the time—such as blues and shimmy dances—while also quoting well-known melodies and compositions to highlight aspects of the narrative. The theme of Death, for instance, is drawn from Josef Suk’s Asrael and Antonín Dvořák’s Requiem. As a satirical jab at Emperor Overall and his “empire,” Ullmann includes ironic references to the German national anthem and Luther’s solemn chorale A Mighty Fortress Is Our God (Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott).

Program

Kammermusik No.1—Paul Hindemith

Filharmonie Brno (CZ), Dennis Russell Davies (US/AT), Angela Waidmann (DE),

Cori O‘Lan (AT)

Der Kaiser von Atlantis—Viktor Ullmann, Peter Kien

Filharmonie Brno (CZ), Emperor (Baritone): Martin Achrainer (AT), Death (Bass-Baritone): Michael Wagner (AT), The Loudspeaker (Bass-Baritone): Ulf Bunde (DE), Harlequin (Tenor): Balint Nemeth (HU), A Soldier (Tenor): Gregor Reinhold (DE), Bubikopf (Soprano): Chinara Azimova (AZ), The Drummer (Alto): Rongna Su (CN)

Musical Direction: Dennis Russell Davies

Stage Direction: David Bösch

Visualizations: Cori O’Lan

Lighting Design and Set Design: Julian Pixel Schmiederer

Costumes: Bianca Stummer

Filharmonie Brno, conducted by Dennis Russell Davies

Pavel Wallinger (Violin), Jiří Víšek (Violin), Petr Pšenica (Viola), Lukáš Polák (Violoncello), Marek Švestka (Double-Bass), Martina Venc Matušínská (Flute), Anikó Kovarikné Hegedüs (Oboe), Jana Krejčí (Clarinet), Jiří Klement (Saxofon), Dušan Drápela (Bassoon), Ondřej Jurčeka (Trumpet), Petr Hladík (Percussion), Maximilian Jopp (Percussion), Veronika Jurčeková (Piano), Lukáš Mičko (Guitar), Jaromír Zámečník (Accordion)

Excerpt from Thomas Mann: Letzte Briefe zum Tode Verurteilter aus dem europäischen Widerstand, herausgegeben von Piero Malvezzi und Giovanni Pirelli; Vorwort von Thomas Mann, München: dtv, 1962. [Original: Lettere di condannati a morte della resistenza europea. A cura di Piero Malvezzi e Giovanni Pirelli. Prefazione di Thomas Mann. Editore: Einaudi, Torino, 1954.]