POST CITY. Habitats for the 21st Century is the theme of Ars Electronica 2015. The festival set for September 3-7 in Linz will scrutinize how cities of the future can best be configured, and consider questions having to do with mobility, work & unemployment, forms of social organization, and security issues in 21st-century megacities.

A thinker who has already been focusing intensively on our urban future is Dietmar Offenhuber, assistant professor of art + design and public policy at Northeastern University in Boston. He got his Ph.D. in urban planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and has published several books having to do with technology and the city. During Dietmar Offenhuber’s recent stay in Linz as artist-in-residence at the Ars Electronica Futurelab under the aegis of the EU’s Connecting Cities project, we had a chance to chat with him about cities of the future.

In our last interview, you said that you regard “informality” as a key aspect of the city of the future. Would you please go into more detail about this.

Dietmar Offenhuber: If you survey a broad spectrum of science fiction visions of our urban future, what you see are cities as highly mechanistic, extremely ordered, very purist configurations. But when we look around us today at where the big cities and new urban centers are and what they look like, then we see that they don’t match these science fiction visions. The big cities of the future will no longer be located in Europe or North America. They’ll be in emerging countries, places we referred to not too long ago as developing countries, but that have already surpassed us in many respects. These are very dynamic places, but in them you’ll be hard pressed to find traces of this all-encompassing modernist principle.

In the 1970s, there were still those who thought that, with modernization, these manifestations of the informal economy and the underground economy would disappear. But this hasn’t occurred at all. Quite the contrary—the informal economies are stronger than ever. Of course, numerous political, economic and social processes are behind this, but another important factor is technology. Communications structures and communications processes are made more informal by technologies. At the same time, though, the informal, in turn, becomes more formal because, so to speak, everything we do generates data. As a result, there’s, once again, a formal component. This is in some sense an interesting hybrid state that emerges between classic order and chaos, and that manifests itself in various ways.

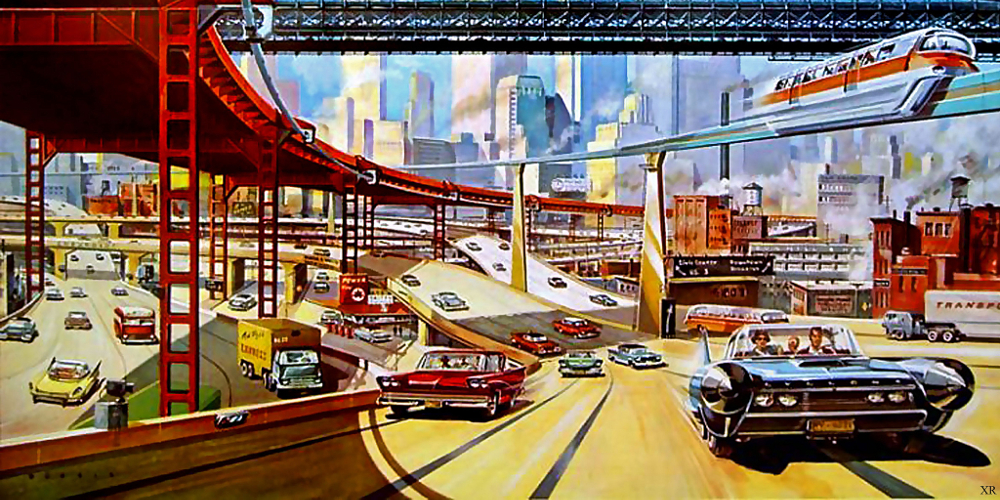

Happy Highway Future (Credit: James Vaughan)

Happy Highway Future (Credit: James Vaughan)

Isn’t that ultimately a contradiction?

Dietmar Offenhuber: Hey, visions of the future are actually always characterized by contradictions and paradoxical situations. Just consider what occurred in the late 19th century: inventions like the telephone slowly proliferated and people thought that direct communication having been made independent of a shared location would cause the dissolution of cities. But at the same time, the telephone made possible the construction of skyscrapers because it enabled the employees of a company dispersed over several floors of a high-rise building to work together. That couldn’t function without telecommunications. There are always highly paradoxical consequences of technologies.

For example, it’s also interesting that architect Frank Lloyd Wright predicted in the ‘30s that the city would disintegrate in the future, and that there would only be a hybrid of the city and the country in which agricultural, residential and industrial uses would be intermingled, and all of this would happen, in his opinion, as a result of telecommunications, mobility and industrial mass production. Of course, this actually has come about to a certain extent on the outskirts of big cities, but at the same time the complete opposite has occurred: cities have not disappeared; rather, they’ve actually become a more dominant part of what’s happening globally. Thus, every process has paradoxical effects.

Back to the Future (Credit: Daniel Ryan)

Back to the Future (Credit: Daniel Ryan)

What will be the greatest challenges facing cities in the future?

Dietmar Offenhuber: There are always lots of challenges. It’s interesting, for example, that, over the last 10 years, UN-HABITAT has published a biennial study of certain global challenges in connection with cities. And they focus on matters like education, health and aging, which are, of course, challenges that exist just like they always have. There have been so-called Millennium Goals—some have been achieved; others haven’t. But it is definitely the case that, for example, global warming has become a matter that’s really being taken seriously by local governments, especially in coastal regions. On the political level, this is still a controversial issue, but in the local context this has long since become a reality in that, for instance, government agencies have reacted by instituting construction regulations. Most cities will definitely be dealing with this for a long time to come.

The term “digital city” is assuming increasing significance. A metropolis should become a “smart city” which is to say networked and intelligent …

Dietmar Offenhuber: The term “smart city” actually comes out of a particular industrial, commercial context. The whole smart cities discussion has emerged in recent years in the wake of the real-estate crash, in that the American government and other governments reacted to it by financing improvements to urban infrastructure. As a result, various firms such as IBM and Cisco that, in previous decades, had been selling, above all, network hardware and network technologies to cities for schools, municipal agencies, etc. saw the possibility of opening up a new market. The term “smart city” is thus actually a commercial version of offering infrastructure management.

Nevertheless, I wouldn’t equate that with the term “digital city,” since it’s actually the case that almost everyone has a smartphone and constantly uses site-specific apps that, of course, massively influence our behavior in an urban setting—for instance, when it comes to arranging a place to meet. Our everyday behavior is very strongly influenced by digital technologies. Under the heading of so-called civic technologies, there are a lot of visions of a potential future that have been derived from already rather widespread possibilities of participative urban design and municipal administration. The difference between this and a smart city is that, here, all the technology is already available.

Dietmar Offenhuber during his residency at the Ars Electronica Futurelab (Credit: Magdalena Leitner)

Dietmar Offenhuber during his residency at the Ars Electronica Futurelab (Credit: Magdalena Leitner)

Constantly being hooked up online doesn’t only deliver benefits; it also raises issues involving, for instance, the protection of privacy …

Dietmar Offenhuber: Of course, there’s been a lot of talk about the private sphere, but the real question is how to make data capture transparent. How do you find out that data is being gathered, and who decides what happens with the data that’s been stored? In this context, I like to talk in terms of the legibility of infrastructures that store personal data. Accordingly, my approach in this direction is that it somehow has to be possible to register the presence of these infrastructures. It’s also important that individuals are able to see what the federal government or the municipal administration does with the stored data, and that people can possibly have a say in this matter.

You previously mentioned participative urban design. Who can/may/should design a city? How important is it for citizens to be able to get involved in the redesign process to bring forth the city of the future, and how realistic is this participation?

Dietmar Offenhuber: That’s a very good question! Participation is a word that always has exclusively positive connotations, although actually this is highly debatable. In the ‘60s, political scientist Sherry Arnstein stated: “The idea of citizen participation is a little like eating spinach: no one is against it in principle because it is good for you.” That was meant sarcastically, of course, since, in many instances, participation is supported only as long as this doesn’t trigger a discussion of sharing power and control. Arnstein differentiates among several levels of participation. On one hand, participation is used strictly as therapy or as pseudo-participation, which is simply a matter of letting people give some input without really allowing them to influence what ultimately happens. On the other hand, participation is something that really is a matter of collaborative design and joint decision-making. So, you have to clearly distinguish what sort of participation we’re talking about. What advantages accrue to the municipal government and how do city dwellers benefit?

At the same time, you have to say that there are also negative aspects of participation. When civic technologies are in play, the whole process can quickly degenerate into incrementalism. Every participant is responsible for doing his/her part, but this acts to cover up the actual systemic problems. For example, this huge problem with all the plastic bottles that now make up such a high proportion of a city’s garbage emerged for the first time in New York in the 1970s. Then, municipal government agencies considered an approach whereby they would simply tax all the beverage manufacturers and simultaneously make them responsible for disposing of the trash they produce. But then the beverage manufacturers did something pretty sly—they said that this is actually the consumers’ responsibility and everyone has to pitch in. The consumers should recycle and, to facilitate this, the beverage manufacturers launched a participative project that ultimately became a recycling system. The city picks up all the plastic bottles once a week and finances this with taxes. Thus, what actually was originally to have been paid for by the beverage manufacturers is now the responsibility of individual citizens, who have to provide the financing and do the work to boot.

A big problem with participation is that it quickly becomes a matter of individualizing responsibility. But, of course, I firmly believe that the city and the municipal administration must necessarily become more participative for the simple reason that there are now more communication channels and information is easier to exchange.

Today, half of all human beings live in a city. Is it possible, in your opinion, that there will someday be a reversal of trend and population will flow back to rural regions?

Dietmar Offenhuber: Yes, I certainly do believe that! I mean, there will surely come a point when downtown real-estate prices become so unbearable that people move back to the suburbs.

Since late November, Geo-Cosmos has displayed an animated film by Dietmar Offenhuber and the Ars Electronica Futurelab. “Sorting Out Cities” is the title of a projection that can depict a wide array of urban data.

[bio img_src=”https://ars.electronica.art/aeblog/files/2015/03/Dietmar_120x120.jpg” alt_img=”Dietmar Offenhuber”] Dietmar Offenhuber is Assistant Professor at Northeastern University in the departments of Art + Design and Public Policy. He holds a PhD in Urban Planning from MIT, studied at the MIT Media Lab and TU Vienna. Dietmar investigates urban infrastructure such as formal and informal waste systems and has published books on the subjects of Urban Data, Accountability Technologies and Urban Informatics.[/bio]

More information about the Ars Electronica Festival 2015: https://ars.electronica.art/postcity/