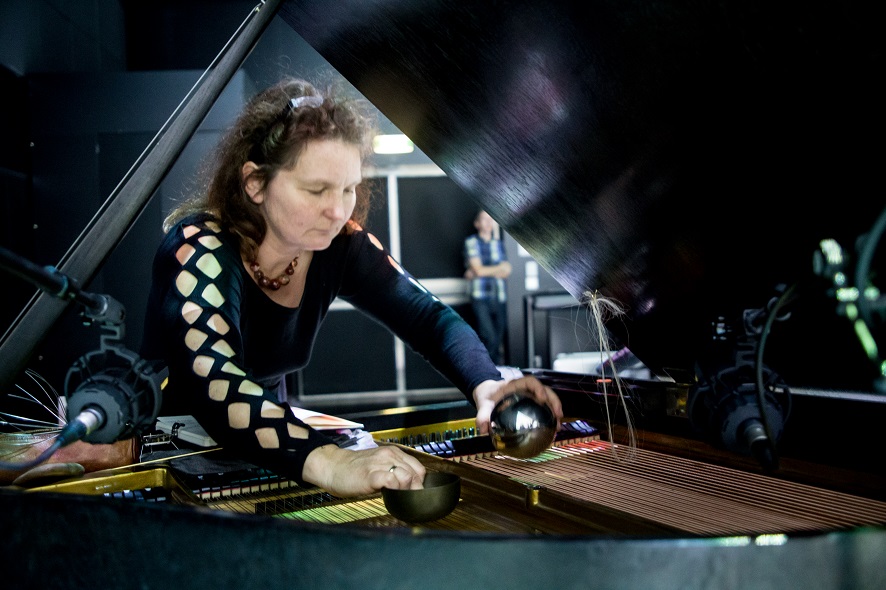

Karen Schlimp’s piano doesn’t look out-of-the-ordinary, but what began life as a keyboard instrument can do a lot more. Sometimes its interior reverberation space resonates via key-driven hammers, and sometimes the musician applies a bow directly to specially-constructed strings. Her discipline is called extended piano, a genre designed to expand the realm of musical possibilities and use the piano as creatively as possible.

To hear how exactly that sounds, be in Deep Space at the Ars Electronica Center on Friday, December 1, 2017, when Schlimp appears with Jaap Blonk (sound poet) and Klaus Hollinetz (electronics) in a concert entitled UNDER YOUR SKIN/Bodyterms—experimental music meets human anatomy, microscope images of the skin serve as scores, and medical terminology becomes verbalized art.

In this interview, musician Karen Schlimp tells us why medicine and music merge in her work, how much space experimental music leaves for improvisation and what concertgoers can look forward to.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

“UNDER YOUR SKIN” is a concert of experimental music. What do you have in store for us?

Karen Schlimp: We’re three musicians who create music on the basis of images of the human body made by a microscope—in medical terminology, histological sections. So this is microscopic anatomy. For this concert, I’ve selected images of the skin—from the surface down to the subcutaneous layers—and thus the title UNDER YOUR SKIN. The images describe the way from exterior to interior. What does it look like under our skin? Accordingly, it’s a concert with images accompanied by experimental contemporary music. Our three musical elements are the piano (including its resonating body) the voice with all possible vocal manipulations, and electronics.

That explains a little about what’s meant by extended voice or extended piano. Maybe you can go into this a bit more?

Karen Schlimp: Extended means broadening the music’s expressive possibilities. In the case of extended piano, you not only play the keys conventionally; you also play the piano’s interior. I have a piano that I’ve had customized—for instance, there are strings I can play with a bow or create rhythm on. So, it’s a piano, but with extended tonal capabilities. You can pluck the strings or play with a bow, make it a percussion instrument, or simply use it to generate sounds.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

What sort of reaction has this sort of music garnered within the music scene?

Karen Schlimp: On one hand, there are those conservatives who want the piano to be played conventionally. But in contemporary music, there’s also a huge current according to which you’re not on the leading edge if you’re not inventing new sounds; if a performance doesn’t showcase a new sound, its passé. Throughout the history of music, instruments have been developed further in accordance with what the music called for. At present, there’s a need for lots of sounds. Now, most musicians expand with electronics, but there are also those who have built new instruments like I’ve done with this piano. Or that expand the voice! Jaap Blonk the #1 European voice artist. Just like I enhanced my piano to provide new tonal options, he’s expanded his voice as an instrument. He truly does everything you can possibly do with a human voice. He calls himself a language poet; he works with letters, with sounds; he even has his own notation. He’s developed the voice as an instrument.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

How does the interplay among you work?

Karen Schlimp: We do free composition—in music terminology: concept improvisation. The material with which we’ll play is determined in advance, and the images I’ve selected serve as the graphical score. There are some elements that I’d like to be played 1:1—for instance, when you see a cell that’s represented in the music with a staccato sound or a percussive sound. That’s why I call the images histological scores—because I translate what I see into musical motifs. In the case of cartilage cells—that is, isogenic cell groups—this works very nicely. In concerts, I represent them with chords. Or I translate certain arrangements of cells into particular tonal sequences. I’ve also established my own notations: in an image of cell groups, the notation shows chords of certain pitches.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

Why does your music focus so intensely on medicine?

Karen Schlimp: This is a personal story. Actually, I’ve always played an instrument but, as a girl, I wanted to be a physician. So I studied medicine parallel to music, but at some point I decided to concentrate completely on music. As a medical student, I was always fascinated by microscope images, and that has stayed with me ever since. I’ve always wanted to make music out of this; to set the images to music. To me, these are the most beautiful images, and beautiful colorations too. The structures in the body—for me, this is art. I’ve been composing for some time now, and I’ve long been into improvisation. And the result of this was a vision to set histology images to music. And then I was fortunate enough to come into contact with the Boltzmann Institute, which made these images available to me. It’s not easy to find good images and to have them placed at one’s disposal. The Boltzmann Institute’s staff worked for weeks to provide me with images. Above all, Sylvia Nürnberger of the Medical University of Vienna was very helpful. She repeatedly asked: What exactly is the artistic take on this medical structure?

Did the interplay with a medical perspective change your artistic perspective?

Karen Schlimp: Not the artistic perspective. But when the physician in me says that that’s the transition from cartilage to bone, this naturally flows into the music. I also use medical terminology, which sound poet Jaap Blonk can improvise with. I choose terms that are appropriate to the theme. Plus, when something’s percussive, I use other words than I would if it were a sound. With the word chondron [cartilage cell], you can work percussively—for example, when you say “chon-chon-chon”. Or you use the “O” in the word, draw it out so that what the picture represents is also shown in some way. My musical treatment of an intestinal cell wouldn’t be the same as of a skin cell.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

Do the audience members get the connection between the image and the music?

Karen Schlimp: There will be pieces in which it’s obvious, and there’ll be pieces in which it isn’t. I’m not a big fan of this 1:1 translation. Naturally, there are particular points at which you see and then hear a structure, but it’s not always that way. There are pictures of the body that, to me, look like an interior landscape. I come to terms with this musically on a totally different level. Klaus Hollinetz works with this, for example, in terms of field recordings. Parts of the body that, to me, resemble a landscape are represented in the music on another level and not translated graphically 1:1. Overall, there are three kinds of translations—graphical translation, association, and poetic translation. What does it mean to feel? One piece entitled “Skin Poems” deals with sensation—what perception and feeling actually are.

How much latitude for improvisation is there in such a performance?

Karen Schlimp: The concert is improvised but there are guidelines. We’re working in the area of free composition or concept improvisation, so certain decisions are made in advance as to which material accompanies which image, or stipulations as to time. Also the lineup—who plays when—is predetermined.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

So it’s interesting for you every time—never knowing exactly what’s going to come out.

Karen Schlimp: That’s part of the appeal of improvisation. I’m an improvisation artist and I find that tremendously stimulating. It’s like tightrope walking—you know you can do it, but you can fall off nevertheless. The beautiful thing is that you can integrate everything happening all around. When I’m improvising, I can react to another musician; I can create a new piece together with him/her. And I can play off the energy coming from the audience; I can play with the audience. I’m very excitedly looking forward to this concert, since I’ve never played on this jumbo-format screen in Deep Space at the Ars Electronica Center. I’m curious about the impact of the stage in comparison to the music.

Deep Space is really another dimension …

Karen Schlimp: Which I think is wonderful! In Deep Space, you get the feeling that you could climb inside the body. My impression is that you really get into the picture more than you do when you just see it projected somewhere. It’s a fabulous opportunity—you sit amidst the image and hear music that represents it in some form.

Karen Schlimp was born in 1968 in Carinthia. She attended the Viktring High School of Music, and studied piano, flute, voice and violin at the Carinthian State Conservatory. She learned to be a piano teacher at the mdw–University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, earned a performance diploma at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London, and also received postgraduate training in improvisation at the University of Music and Theater Leipzig. She has been an instructor of piano, teaching and improvisation at Anton Bruckner University in Linz since 1995, and has also taught at mdw since 1996. She achieved habilitation in improvisation at Anton Bruckner University in 2009.

The “UNDER YOUR SKIN/Bodyterms” concert is set for December 1, 2017 at 7 PM in Deep Space at the Ars Electronica Center. Admission is free of charge. Details are available here.

To learn more about Ars Electronica, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter, and check us out online at https://ars.electronica.art/news/en/.