Waltraut Cooper would be easily recognizable even if she didn’t have bright red hair! Her hearty laughter reverberated throughout the high-ceilinged spaces of Landesgalerie Linz as she provided a first glimpse of her new exhibition there. This show featuring selected works by the renowned Linzer media artist runs until January 21, 2018. The centerpiece is a jumbo-format “Klangmikado” [Sound Pick-up Sticks] from her “Digital Poetry” series, a work that’s been reconstructed for the show in Landesgalerie. Other works from that series now on display there include those that appeared at four Venice Biennales, and documentation of her famous “Regenbogentrilogie” [Rainbow Trilogy].

Colorful and intensive are terms that can well be applied to all her works. Her expressive vocabulary is reduced but impressive. In this interview, Waltraut Cooper gave us an account of her beginnings as a media artist in the 1980s, talked about why she’s so fascinated by light, and explained what’s behind “Digital Poetry”.

If you’d like to see Cooper’s light installations for yourself, you can do so from December 19 to 24, 2017: For this year’s Ö3 Weihnachtswunder (Public Radio Station Ö3’s “Christmas Miracle”) at Linz Main Square, the media artist developed a light spectacle for Ars Electronica Center’s media facade, visualizing the music live on the building.

You’re known for your work with sound and light. What’s the source of this fascination?

Waltraut Cooper: As a mathematician, I come from a background in which technology plays a major role. Technological aspects have always fascinated me. My work with light in particular was actually an outgrowth of having seen “Other Avant-Garde”, a very large exhibition that included works from all over the world. The time when I began doing art was very much oriented on the future, and the avant-garde played a big role. There was a very pervasive spirit of optimism, and that went for women too. This was the first time that there was a huge outpouring of sentiment that women have to have the same rights as men. This was precisely when the exhibition “Other Avant-Garde” ran in the Brucknerhaus, and I was invited to contribute a work. I was so fascinated by the Brucknerhaus’ geometric exterior that I got the idea of creating diagonals of light right on the façade. That was the beginning. I found it so fascinating to work with light. And afterwards, this fascination simply grew and grew.

What is it about light that interests you so?

Waltraut: Light is a wonderful medium, it’s so powerfully expressive. You can work with light on a large scale—that’s what I like. The bigger, the better, so to speak! These possibilities aren’t to be had otherwise. I find light magnificent. Of course, it depends on how you use it. But I express myself in very reduced terms in any case. That probably comes from mathematics, which functions so well in describing the world because it offers a means of expression that is as abbreviated as possible. Consider, for example, one of the laws of physics, E=mc2, a formula that everyone’s familiar with. You’d have a hard time expressing this principle as effectively using words. The world wouldn’t be explicable without mathematics. One concentrates on the essentials, and anything that’s extraneous to the matter at hand is left unsaid. And this probably asserted itself in my way of thinking. My absolutely highest priority is to convey what something boils down to. What’s the heart of a matter? This is why I prefer to work in highly reduced terms. When you work with light, if you don’t watch out, it can get totally kitschy. You have to really keep your eye on what’s essential; what am I trying to express, and how? In this sense, I especially like working with light.

Credit: Oö. Landesmuseum, A. Bruckböck

You created the “Digital Poetry” series in the ‘80s. Please tell us a little about this.

Waltraut Cooper: This was when, suddenly, for the first time, individuals could acquire a personal computer. Of course, I was fascinated by this medium. I wanted to create works that couldn’t be created otherwise. What can you do with a computer that can’t be done any other way? Computers enable you to directly interconnect forms of artistic expression—visual, verbal and musical. It’s not the case that I listen to music and write something down simultaneously, or in tune with it—NO. Direct, 1:1. Transformation from one form of artistic expression to another—digital code offered a way to achieve this. And this, of course, opens up a huge spectrum for artistic work.

So, in “Digital Poetry”, are artistic works transferred into digital form?

Waltraut Cooper: No. It’s frequently the case that I come upon the number via the naming, via the word, and then I arrive at the aesthetic object. This is the transformation that takes place. For instance, the picture entitled “MONA” is one of the works in the Landesgalerie exhibition. This is an image from the 2016 Biennale; in it, my granddaughter Mona goes through a room with one of my light installations. I take the word Mona and digitize it, which means that it’s now just a series of 0s and 1s. The picture, which is a photo of her I had taken, is now the point of departure of a new image. The light installation is thus practically directly transformed into an image.

A similar example is the work in the Austria Center in UNO [United Nations] City in Vienna. There was a competition with several locations, and I was assigned the largest location. The assignment was to design a gigantic, 60-meter-long frieze in the lobby. At that time, dread of nuclear war prevailed; for the first time, there were efforts to hold peace talks or a disarmament summit. That’s why I entitled my work “Friedensfries” [Peace Frieze]. I took the word UNO as the point of departure and digitized it. Thus, I start with a word, and that becomes numbers—i.e. digitized into 0s and 1s—and they in turn become an artistic object. For the 1, I took an emergent flash and for the 0 an emergent flash, and the upshot of that was the design of the frieze.

Another example is a work I produced for the University of Graz. I had won a competition for the design of a new building for one of the departments. My idea was to play up the initials of the department on the new building. The initials were expressed not only in light and color but also as sound. Once an hour for a brief time, it was possible to hear them expressed as sound.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

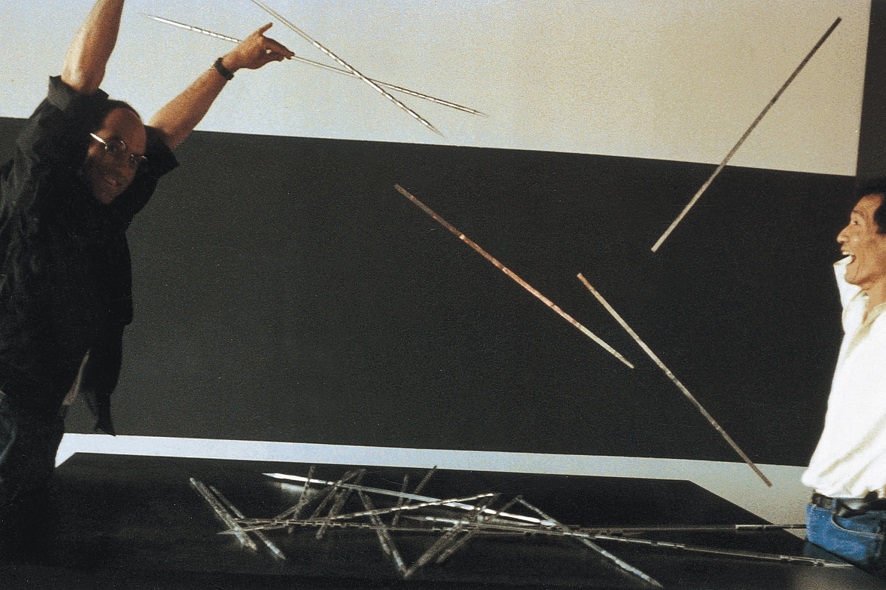

Sound also plays a key role in “Klangmikado” that was reconstructed for the Landesgalerie show.

Waltraut Cooper: The first “Klangmikado” was way back in 1984, when it was shown in an Ars Electronica exhibition. Then in 1987 Ars Electronica invited me to technically upgrade the work. This was an assignment I was very happy to receive. This work had really gotten around—it was shown in Hamburg, Vienna, Italy, at the Image du Futur festival in Montreal, in Boston, and in the Bronx Museum of the Arts in New York. And now I’m absolutely delighted that it’s been reconstructed, since the original was unfortunately destroyed by flooding in Linz. Now, I’m so pleased that “Klangmikado” is back.

What awaits those visiting “Klangmikado” in the Landesgalerie?

Waltraut Cooper: There’s a big table with supersized pick-up sticks—each one about a meter long and wrapped in aluminum foil. This isn’t just an allusion to a conventional game of pick-up sticks, and it’s not only fascinating from an aesthetic point of view; it’s also technically important. Imbedded in the tabletop are sensors that react to the foil wrapping and trigger music. This music is by Salzburg composer Gerhard E. Winkler, who created the music for the original “Klangmikado” and has now composed this new piece for it.

Credit: Bildrecht Wien 2017

So, installation visitors are called upon to move the pick-up sticks…

Waltraut Cooper: They’re invited to play pick-up sticks. Of course, it’s not to be taken as seriously as in an actual game, but the people obviously find that it’s fun and very exhilarating. When the work is exhibited, there are constantly visitors there playing with it.

Generally speaking, many of your works are interactive …

Waltraut Cooper: Then, it’s not just something you can look at; it’s also something you can touch. And not just touch; you can play with it. It’s a process of interpersonal exchange; people play with one another—in this case, pick-up sticks. They contribute to the work of art, especially with “Klangmikado”—every person creates a new composition out of Gerhard Winkler’s music. It’s a collaborative work, so to speak.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

The new exhibition also contains documentation about “Regenbogentrilogie”. What is the essence of this work?

Waltraut Cooper: I got the idea for “Regenbogentrilogie” in 1989 when the Berlin Wall came down, because I had the feeling that a rainbow had to be arched across Europe as a sign of solidarity and the bridging of distances. The question was: How? After long considerations, I decided to start with Austria, even before the end of the millennium. A rainbow is always an indicator of better times to come. In 1999, we were at the end of a century with two world wars, so it was high time for a rainbow bridging the turn of the millennium in the hope of better times. So, I wanted to start with Austria, and then Europe, and finally spread this arc worldwide. So, in 1999, at the end of a century with two world wars, I created a rainbow that spanned Austria. In each of the country’s nine states, an important architectural landmark was bathed in light, each in a different color. And together, they formed a rainbow across Austria. Then in 2004, an event occurred in Europe in connection with which a European rainbow made sense: 10 new member states joined the EU and thereby strengthened peace on this continent. Accordingly, I spanned a rainbow across Europe with significant buildings that were relevant in this context. Finally, 70 years after the end of World War II, I spanned a worldwide rainbow with one building on each continent as the sign of hope for world peace, which I consider the greatest challenge facing us today.

That’s certainly a very hopeful thought!

Waltraut Cooper: If you had said 100 years ago that there would be peace in Europe someday, everyone would have just shaken their heads! And what do we have now? Now we have peace. Now that the world is so closely interconnected, it actually doesn’t make sense anymore to wage war because doing so just destroys our own resources. It used to be that people destroyed resources, but then they were at least acting on the conviction that they were destroying other people’s resources. Today, you can’t say that anymore. The world has grown together to such an extent that everything affects everyone. But we’ve also learned a lot of lessons. That’s why I don’t think it’s so far-fetched to believe that there’ll be world peace.

Waltraut Cooper studied mathematics, theoretical physics and art in Vienna, Paris, Santa Barbara California, Lisbon and Frankfurt. She has shown her works worldwide, including four Venice Biennales and at festivals, exhibitions and galleries in Vienna, Berlin, Rome, Paris, Montreal, Boston and New York. Her works, which focus on media, art and architecture, have been honored with numerous prizes.

The exhibition “Waltraut Cooper. Light and Sound” was produced jointly by Landesgalerie Linz and the Ars Electronica Center. It runs from November 16, 2017 to January 21, 2018 in Landesgalerie Linz. More information is available here. Additionally, you can see one of her light installations on Ars Electronica’s facade in Linz from December 19 to 24, 2017, visualizing Austria’s Public Ratio Station Ö3’s “Christmas Miracle”.

To learn more about Ars Electronica, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter, and check us out online at https://ars.electronica.art/news/en/.