How have recent technological breakthroughs changed the discovery of, research on and presentation of humankind’s cultural heritage? What does Europe’s cultural heritage consist of? And why is considering the past important in the first place?

To get answers to these questions, attend the European Year of Cultural Heritage themed weekend January 27-28, 2018 at the Ars Electronica Center, where speakers will be able to take advantage of Deep Space 8K’s state-of-the-art technology to make their elaborations on cultural heritage come alive! Among the highlights are talks by Dr. Stefan Traxler, staff archeologist at Upper Austria’s Landesmuseum. In this interview, he tells us more.

Credit: Robert Bauernhansl

2018 is the European Year of Cultural Heritage. Why is it important for people to be cognizant of their cultural heritage?

Stefan Traxler: Cultural heritage endows people with an identity. At a time of intense discussions about what Europe is and whether development should be more in the direction of national distinctions, events of precisely this sort are very important to demonstrate what Europe has in common as well as to juxtapose what’s special about the individual regions and thus show that both are justified. National identity is certainly important for many people, but the big picture is that we all inhabit Planet Earth. We’re humankind.

What does Europe have in common? What interconnects the various countries and regions?

Stefan Traxler: We have a common cultural cradle, Greco-Roman civilization. This is manifested even in our language, which includes so many Latin terms. Our thinking and our art have been influenced very strongly by Antiquity. Europe’s Western civilization is utterly inconceivable without Antiquity, or the image of Antiquity that emerged during the Renaissance.

To what extent can a national identity exist in this context?

Stefan Traxler: A national identity is frequently based on current boundaries. Ultimately, we’re moving about within an image of history. There are borders that have come to be for a number of reasons. The question is simply: Does one wish to keep borders in place or break them down?

Credit: Martin Hieslmair

All of Ars Electronica’s activities are highly future-oriented. Why is it rewarding for such an institution to peer retrospectively into the past?

Stefan Traxler: I believe that people who don’t consider their roots will also have problems giving thought to their future. We’re familiar with this from a familial context too; our family has made an impression on us; we’re shaped by our milieu. And this is exactly how it’s been in human history. History has had an impact on us; we’re also a product of our larger environment, of our nature—even if we’re not always mindful of this or ever repress it. This is why I believe it’s very important to reflect on one’s roots and, on this basis, to conceive one’s mental world in broader terms than strictly from a personal perspective.

New technologies are changing how this retrospection—and even the discovery of our cultural heritage—takes place. What changes has technology wrought with respect to cultural heritage?

Stefan Traxler: Quite a bit has transpired in this respect over the last 20 years. Here, I’m referring above all to archeology. Technological developments like geophysics—ground-penetrating radar, geomagnetics—have triggered a quantum leap in archeology. At a dig in the past, you had no idea where to start and where to stop. Now, a large-scale geophysics scan immediately gives you a good idea of the dimensions of a find. In some cases, you even have depth information, and three-dimensional images of the soil layers can also be generated. Even if their precision cannot match that yielded by actually excavating the site, we know in advance what we’re dealing with. And scientific methods are now part of the standard repertoire of evaluation techniques. A quantum leap truly has taken place, and it has certainly not yet reached its zenith.

What about the possibilities of presenting cultural heritage? How have they changed?

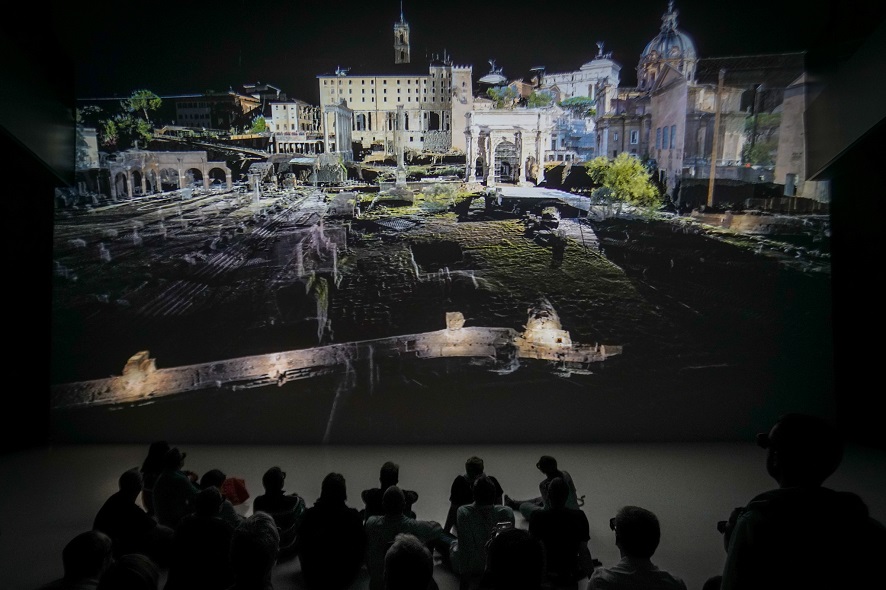

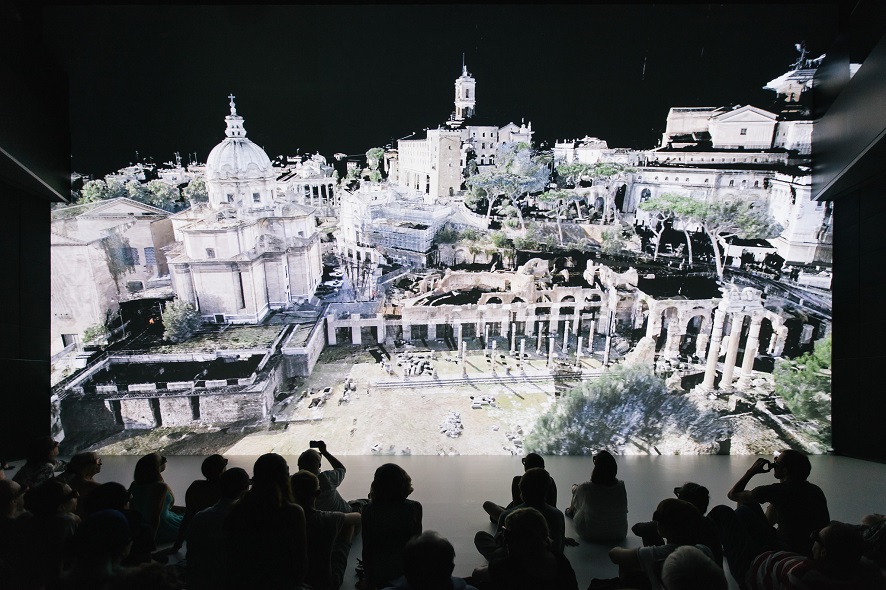

Stefan Traxler: The presentation possibilities have greatly increased due to these breakthroughs. Now, everything is geo-referenced and measured down to the centimeter. In presentations, I can overlay any number of strata, generate all sorts of images and move about—or even fly through—3-D scanned archeological sites dating back to Antiquity.

Credit: commons.wikimedia / Magnus Manske

This will be your topic in Deep Space 8K during Cultural Heritage weekend. What can we look forward to?

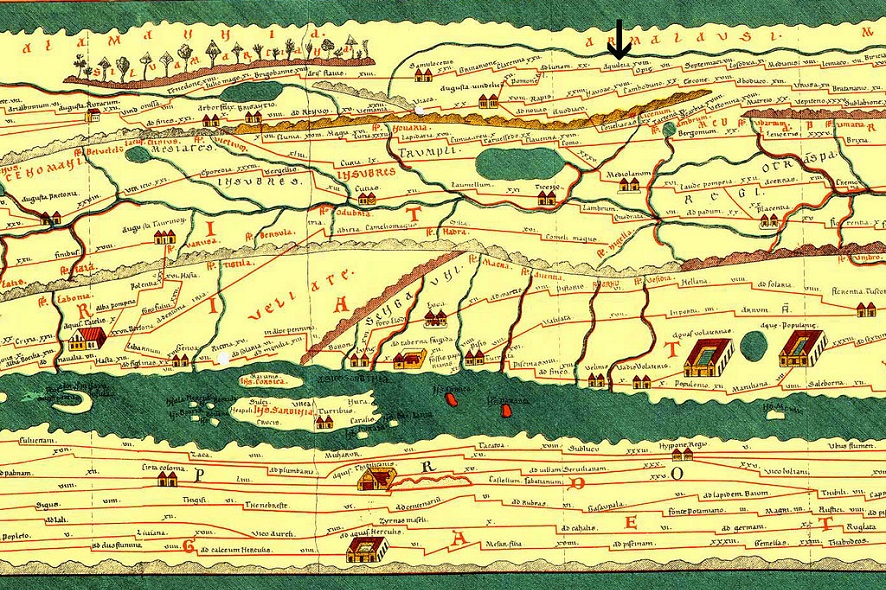

Stefan Traxler: The first of the three talks I’ll be giving in Deep Space will focus on a superb document, one that is perhaps the most important testimony to the achievements of the Roman Empire that we possess today, the Tabula Peutingeriana, which has been placed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. This map—measuring 6 meters, 40 centimeters by 34 centimeters, and thus elongated like a modern-day subway diagram—depicts the 200,000-kilometer network of roads at approximately the time of the Roman Empire’s greatest extent. It shows several hundred cities, various crossroads, and also gives the mileage between key points. All according to the motto: All Roads Lead to Rome! Ars Electronica offers the opportunity to screen this map at a degree of detail that’s impossible to achieve elsewhere.

Tell us something about your second talk, which also has to do with Ancient Rome.

Stefan Traxler: “Rome’s Invisible City” is a BBC documentary that was edited down to about 15 minutes in length for Ars Electronica. Moving about three-dimensionally mostly in subterranean realms brings out facets of the city to which conventional tourists never have access. One moves through underground quarries, flies through sewage canals, through the Aqua Virgo, a 2,000-year-old water main that’s still in use, and various architectural landmarks such as the Pantheon. It’s Rome from a novel perspective.

Credit: Florian Voggeneder

You’ll also be showing images of lime kilns in Lauriacum, which is now known as Enns, Austria…

Stefan Traxler: There’s a smooth segue to the lime kilns of Enns. Edifices like the Pantheon would have been impossible without the Opus Caementitium and without the Romans’ amazing construction techniques. They invented a mixed concrete that, due to various additives, was incredibly durable, could hold underwater, and achieved strength unmatched by modern-day cement. What we’re building today probably won’t be around in 2,000 years.

What did the Romans do differently?

In any case, you need Roman limestone and a lime kiln. This is where the battery of kilns in Lauriacum comes into play. This is, at present, the largest known lime kiln complex, with 12 kilns, each with a capacity of 31 cubic meters. Mass production on this level wasn’t achieved again until the 20th century. This complex in Enns was set up 1,800 years ago. This limestone was mixed with various additives—sand, water-binding elements, brick chippings or, in Italy, even volcanic ash, which is what produced this incredible durability. At the same time, they built in a way that used more stable, heavier and harder materials on the bottom, and then lighter materials further up. Precisely this technique was used to excellent advantage in constructing the Pantheon’s dome.

Credit: Martin Hieslmair

So, Enns brings us to your third talk about archeological digs in Upper Austria. And in 3-D, no less!

Stefan Traxler: Our exhibition entitled “The Return of the Legion. Roman Heritage in Upper Austria” opens on April 27, 2018. The main venues are Enns—the town of Lauriacum, which was also the sole army base in the Roman Province of Noricum—Schlögen and Oberranna. For our exhibition, we excavated at these three locations, all of which will be accessible by visitors. We did 3-D scans of these digs and post-processed the resulting material so the details can be seen beautifully in Deep Space. So, as a sort of sneak preview of the exhibition, we’re screening high-resolution images of these extraordinary archeological sites.

We’re featuring two buildings and one of the 12 lime kilns. Plus, the kiln was just full of incredible finds, since it was used as a sort of ancient garbage dump. We found thousands of objects that provided us with insights into the culture of everyday life back then. In Schlögen, we excavated a Roman bath, a small but very nicely executed spa that lets you see how superbly this was engineered. Oberranna is the site of one of the best-preserved Roman edifices in Upper Austria, a Quadriburgus, a fortifications complex from Late Antiquity. Some of the two-meter-high walls are still standing; the foundation is up to one-and-a-half meters deep. There’s also a medieval cellar that was built into a Roman tower. When you stand there, it’s like being in the 15th and the 4th centuries simultaneously. These are some of the absolute highlights that will be featured at the exhibition, which we’ll now be previewing at the Ars Electronica Center.

Stefan Traxler was born in 1975 in Linz. He studied archeology, ancient history and antiquities at the University of Salzburg. He works as an archeologist at Upper Austria’s Landesmuseum, where his responsibilities include both scholarly and administrative matters as well as management of the digs in conjunction with this year’s exhibition, “The Return of the Legion”: www.landesausstellung.at

The themed weekend marking the European Year of Cultural Heritage is set for Saturday & Sunday, January 27-28, 2018, in Deep Space 8K at the Ars Electronica Center. Complete details about Stefan Traxler’s talks and all other scheduled events are available on our website.

To learn more about Ars Electronica, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter, and check us out online at https://ars.electronica.art/news/en/.