The interview is also available in Japanese and German.

As is so often the case these days, we meet with our discussion partners virtually, via video chat. We’re connected with Naohiro Ukawa, Japanese artist and founder of DOMMUNE, which is a platform that opened in 2010 as the first live streaming studio in Japan, and Gerfried Stocker, the artistic director of Ars Electronica. And although both are sitting in their home offices in Japan and Austria thousands of kilometers apart – due to the worldwide pandemic – they are united by a central theme: the fascination about Isao Tomita.

TOMITA information Hub and Prix Ars Electronica have initiated the Isao Tomita Special Prize to support musicians and sound artists in their work with a prize of 5,000 euros and a performance at the Ars Electronica Festival. What makes Isao Tomita so special, and what can we all learn from the electronic music pioneer who died in 2016, how we can deal with the fact that artificial intelligence will change creative music-making, and what role nature plays in all of this, this is explained in the following interview.

Naohiro Ukawa and Gerfried Stocker

Perhaps the best way to start is with this question: When did you first hear of Isao Tomita?

Naohiro Ukawa: That was in the first grade of junior high school. It was the time of the techno-pop boom in the early 1980s, and Japan was moving from high economic growth to a bubble economy. In such booming times that I became aware of the synthesizer music of YMO (Yellow Magic Orchestra). Formed in 1979, the electropop unit was one of several techno pop groups that emerged at the time, and their music made it to the Japanese song top 10 charts at the time. This was a real shock in the Japanese music scene, when synthesizer music, with no lyrics at all, appeared on the charts alongside rock, pop and folk music.

“Rydeen” was the big music hit of YMO at that time, the band became known nationwide, bringing schoolchildren into the fold and starting the synthesizer boom. I was in the fourth grade elementary school kids – and at the time, the super high speed car such as Lamborghinis, Ferraris and Maseratis were the trend among children, and like Ultraman and other superheroes, they were the object of admiration, giving rise to a strange fad: the supercar boom. Even I didn’t have a license (*smiles*). This meant that, like supercars, we pupils of course could not be bought MOOG synthesizers. YMO spearheaded that movement, and their support member Hideki Matsutake was manipulating the synthesizer at that time – and he originally inherited that from Isao Tomita when he was his assistant before in the 1970s.

The 1970s were also the time when Isao Tomita brought electronic music to the public…

Naohiro Ukawa: Isao Tomita was in the same class as Asei Kobayashi (a famous Japanese composer) when he was in high school, and from then on he studied composition, and at Keio University he studied music theory. When he was in Osaka to record music for the Toshiba IHI pavilion at the 1970 Osaka Expo, he went to a record store at that time, he became aware of “Switched-On Bach” by Walter Carlos (Wendy Carlos) and became interested in synthesizers.

After Isao Tomita finished his work at the Expo, he bought the Moog III-P synthesizer – a huge device (in Japan, it’s called ‘chest’) that cost more than 10 million yen at the time. You may know the anecdote that this huge electronic musical instrument without keys was stuck in customs for a long time when it was imported from the US to Japan because it was initially mistaken for a military equipment. He finally showed a photo of Keith Emerson performing on stage to customs and they released the Moog III-P synthesizer…

He then set up the Moog III-P synthesizer at home, and since there weren’t manuals for it, he spent a lot of time creating sounds from it. In the beginning, he also had doubts about whether it was a waste of money or not. But then after one year and four months of work, he landed a huge hit with the album “Snowflakes are Dancing” – but only because the American record label RCA gave a contract and then released it. He went to several Japanese record companies beforehand, but rejected because no one knew what genre of music it was or what shelf of the record store to put it on. But it reached number 2 on the Billboard Classical Chart and was eventually nominated for the Grammys. It was a long trial-and-error process, but Isao Tomita created the production style with synthesizers, which he also passed on to Hideki Matsutake who supported YMO.

And later on you met Isao Tomita personally…

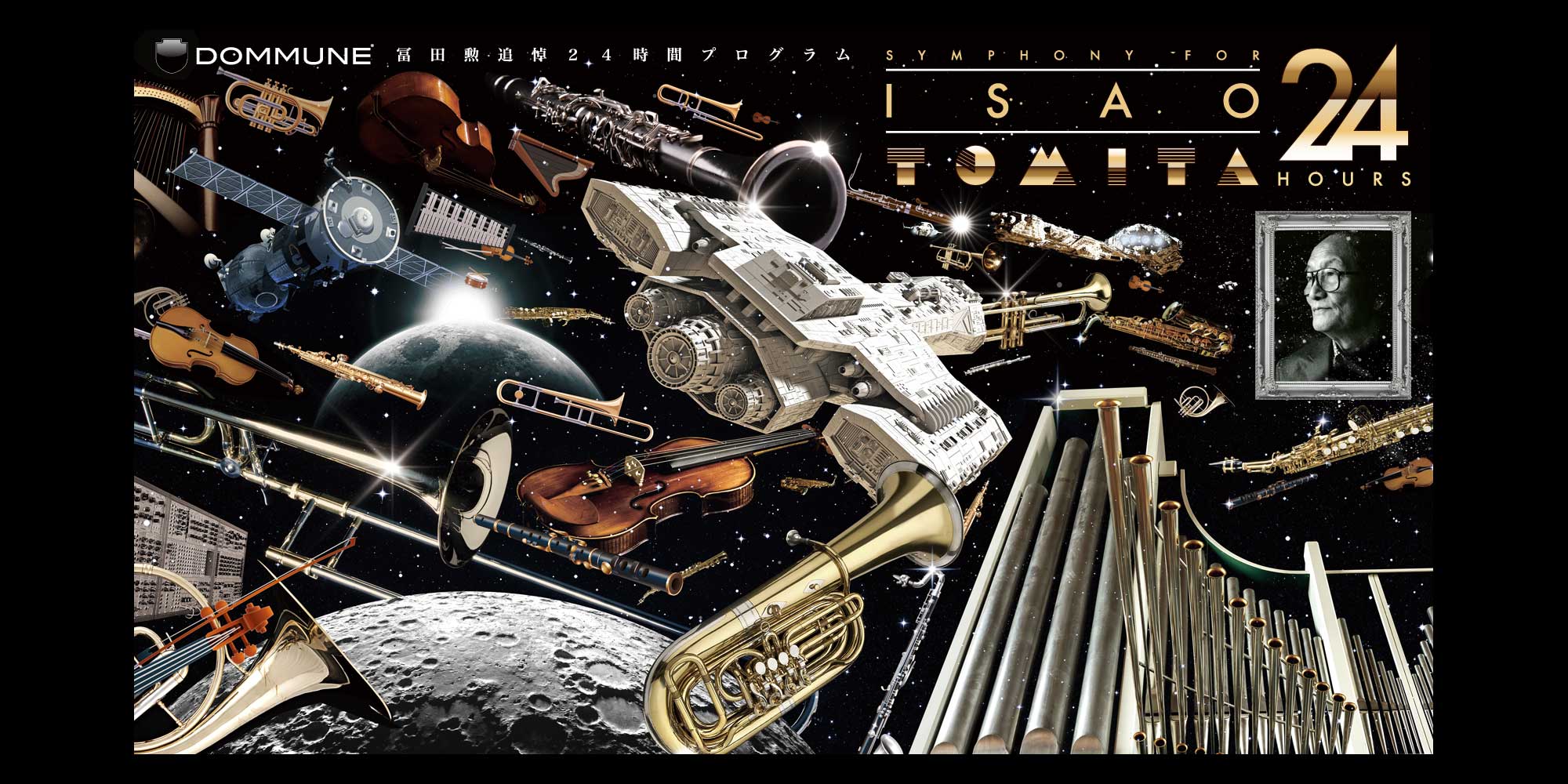

Naohiro Ukawa: Yes exactly, after I founded DOMMUNE I was able to meet Isao Tomita personally in 2010. We met dozens of times since then in the last years of his life and had a dialogue about many topics in detail, we organized live performances together, designed record covers together, emailed a lot and exchanged many ideas with each other. Finally, after his death in 2016, we hosted a 24-hour livestreaming on DOMMUNE in memory of Isao Tomita in honor.

The same introductory question to you Gerfried, when did you first hear of Isao Tomita?

Gerfried Stocker: Well, actually I remember very well the first time I heard music by Isao Tomita in 1978. It was one of the very first experiences as a teenager with another universe, when I was growing up in a rather small village in the countryside and a friend, who of course was much older than me, came by with this record by Isao Tomita and we listened to classical music played on a synthesizer.

That was a really exciting experience for me – it was not only a completely new way of expanding the possibilities of technology and electronics, but one of my first serious encounters with classical music. Hearing Isao Tomita interpret the entire orchestra using only synthesizers also encouraged me to explore much more deeply what classical music actually means. This is one of the very great achievements of Isao Tomita – to open up two universes and connect them!

It is incredibly important to understand this tremendous achievement from our perspective today. We can create all the different sounds we can imagine today, and it’s impossible to tell which sound is coming from a real instrument and which is coming from a synthesizer. Anyone who witnessed that time knows what a painstaking job it was to produce, record, and perform live all those sounds with the modular synthesizers. With his high level of quality, Isao Tomita really challenged the engineers and the people who produced this technology, pushing it to the limits and beyond.

I think his incredible work with classical music, with Debussy, with Stravinsky and later with Holst’s “The Planets” was also a very important step… an achievement that helped liberate electronic music. It took someone like Isao Tomita to say, “Okay, this is what we can do with synthesizers, so don’t ask us anymore if this is a real instrument or not. Look here, we can do anything we want with it.” Isao Tomita has taken the synthesizer, which previously belonged only to engineers and technicians, to a new level.

Isao Tomita has not only tried to imitate other instruments, but also created completely new sounds…

Gerfried Stocker: Imitating, that’s one thing, that’s extremely hard work. And by trying to imitate, you automatically get off that path. That’s one way you can explore possibilities and then automatically you go to the next step. We have to be very careful with this word of “imitating.” I think the important point is that you open yourself to the world beyond the classical instrumental sound. And then when you’re beyond that, you can really start to be creative.

With Isao Tomita, you have to remember that he had a very traditional classical music education and then he created masterpieces by bringing classical music into the synthesizer. As Ukawa said, he has greatly influenced generations of artists and musicians not only in Japan. He encouraged them to go their own way, and he really showed and proved to them that you can go beyond the limits and that this is the way to go.

Does that also coincide with your view of Isao Tomita?

Naohiro Ukawa: Not only was he the pioneer of real synthesizer music, but he was also the first artist to buy such a new and expensive instrument and take the time to work with it personally. In short, he is the pioneer of desktop music. Before that, there was an experimental music composition studio at NHK the broadcasting corporation in Japan, where composers and engineers worked together to develop music. But Isao Tomita brought his Moog-III-P into his own music studio, where he also stayed in there and spent most of his time, often sleeping on a hammock in the studio rather than at home. So he worked for three years until he finished his album for “Pictures at an Exhibition”.

“Isao Tomita created music that was completely different from the existing structures at the time. Synthesizers were thought to create only linear music, but he brought depth, or more precisely, color to this music. When he talked about synthesizers, he often used the analogy of a color palette, where you could mix several colors into a new one. Module patching for him was like creating a painting from a color palette.”

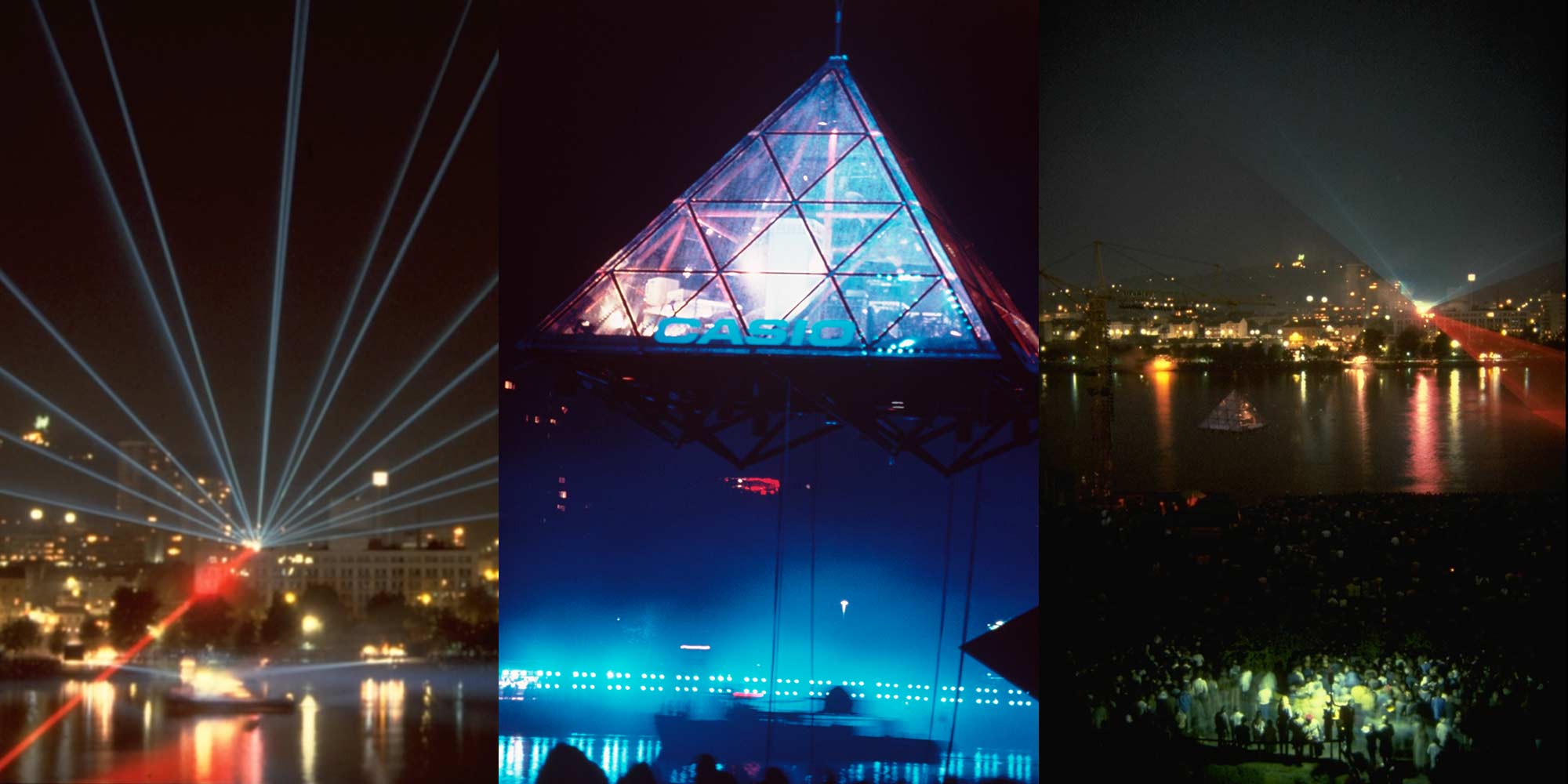

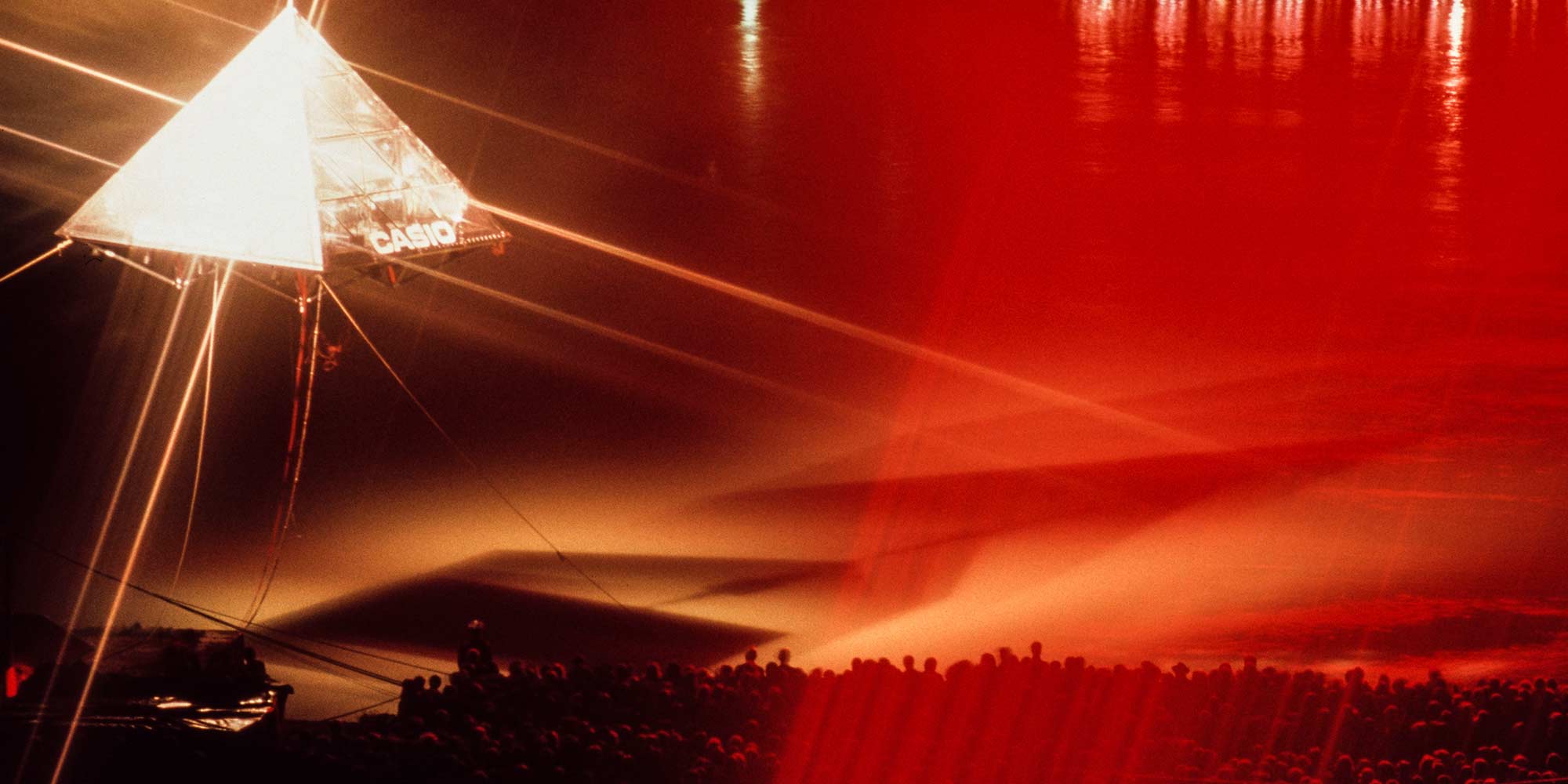

Ars Electronica 1984 – Isao Tomita at the Sound Cloud (Klangwolke), Credits: Andreas Fleiß, Sepp Schaffler

Isao Tomita has also been to Linz several times, and especially in 1984 he thrilled people with his spectacular performance at the Klangwolke…

Gerfried Stocker: Ukawa has already mentioned that he created the music for the Toshiba-IHI pavilion at the Osaka Expo in 1970. At that time, the latest high-end music technology was presented there and everything was now about surround sound and sounds moving in space. He started his SoundCloud project in Linz and presented all his colleagues with a very big challenge: he wanted big sound systems on boats that went up and down the Danube river in front of the audience, he had speakers suspended on a helicopter that flew above the city and the 100,000 spectators, and he himself hovered with his synthesizer in a huge glass pyramid mounted on a crane.

I was too young to witness the spectacle myself, but I later met a lot of people who worked with him on it… engineers, sound technicians, people who took care of the permits for all these things. And everybody said, “Oh my God, that was such a headache, but it was one of the best experiences of my life!”. And that right there is a great example of what art and artists can and must do: Push the boundaries, challenge us to move forward. Isao Tomita has influenced many people and artists, not only through his art itself, but perhaps even more through his way of working.

Isao Tomita in Linz 1984, Credit: Keishi Miura

What Isao Tomita has done so perfectly is to go out of the concert halls and enter the public space. Nowadays we are totally used to huge open-air spectacles with lasers and even thousands of drones hovering in the sky. But you have to imagine it in the time of the early 1980s! Bringing an event like that into public space was almost like a mission to the moon.

“In a way, this was a democratic act, because as Ukawa said, this technology was extremely expensive. Music, especially classical music, was still considered part of the cultural elite. And now this guy comes along, uses this expensive technology, combines it with sacred music, makes it electronic and brings it outside to thousands of people!”

And this is perhaps also the connecting factor why the Isao Tomita Special Prize is now being awarded for the first time as part of the Prix Ars Electronica…

Gerfried Stocker: Isao Tomita was a wonderful role model, and the Isao Tomita Special Prize is a really wonderful opportunity to look for young artists who are just as eager to do what Tomita started in the 1960s with early electronic and modular synthesizers. Now that a new era has dawned and music is about to change completely again…. When we think of machine learning and artificial intelligence, our idea of creativity and music will be put to the test again just as it was in the 1960s with modular synthesizers.

Does artificial intelligence change the role of artists? What does it mean to be a creator and an artist? The only answer we can have to these questions is to step back up as artists and say, “Okay, we’re going to take the challenge and we’re going to take this technology one step further. We’re going to bring it into the human realm, we’re going to make technology part of the culture!” And that’s exactly what the Isao Tomita Special Prize is about.

What challenges are young artists facing today? Is it primarily artificial intelligence or are there others?

Gerfried Stocker: I think it’s both. There are the challenges that have always been the great challenges for young artists – and that is, above all, to find one’s own way and one’s own identity. On the one hand, it’s about looking at role models and the heroes of the past, listening to what they’ve done, but on the other hand, figuring out what your own position and role are, what you can contribute, and how you can push your own ideas and make them happen. This is a challenge that is universal for art and artists throughout the centuries.

The next challenge is not so different. It is the challenge that every generation of young artists is fortunately always confronted with new possibilities. Throughout history, there have been new instruments and new ways of presenting music. But of course, among all these technological advances today, artificial intelligence is in some ways a particularly big one, because it challenges not only the way we produce music or the way we create sounds, but also the way we express ourselves artistically.

This is a very central question that artists have to ask themselves…

Gerfried Stocker: It’s actually a very big question about the basis of art and being an artist. The question of creativity. And how can we explore that, how can we find interesting, productive ways to work with these really exciting new technologies that are, of course, scary for us in many ways because they really hit the central point of what we would define as purely human, which is to be creative.

“The core of being an artist is creativity. Now there are machines that can at least simulate being creative, and who knows, maybe these machines will already be creative now or in the near future. So what is the role of the human being? And I think there are very good and clear answers to that from the artists. They are now challenged to create their own identity as individuals, and to create some kind of collective idea of what it means to be an artist in the age of this new technology.”

Naohiro Ukawa: Isao Tomita challenged technology and actually opened a lot of new doors for art! He opened a world of electronic music to us, and I think we should think together with artists about what it means to be a post-pandemic society, similar to Isao Tomita. What does the next world look like? And it’s not just about technology.

In his album “Dawn Chorus”, Isao Tomita has taken up the natural phenomenon of the same name, which is created by the influence of sunspots at sunrise on Earth. Antennas can be used to make these electromagnetic waves audible, which sound similar to the chirping of birds at dawn. He field-recorded the process and experimented a lot with it, and Isao Tomita discovered another field for himself, the coexistence with nature in acoustic field with this natural dawn chorus.

With the effects of climate change, the topic of “nature” is much more present than ever…

Naohiro Ukawa: This new way of field recording was very innovative and his connection to the natural environment, fantasies of a cosmic environment, was part of his identity. In 2012 there was a concert called “Ihatov Symphony” where he incorporated the virtual singer Miku Hatsune as a soloist into his performance, trying to incorporate different phenomena of the universe into his music. He has tried to push this inner communication between the earth and the universe throughout his career since the launch of his SoundCloud project in Linz in 1984. He also took a theme on the terrible and devastating tragedy of Great East Japan Earthquake in Fukushima.

While Isao Tomita used the latest and most advanced technology, he also always looked at nature – and that will be one of the most important things after this pandemic: Thinking about nature and not losing sight of the balance between humans and nature. It’s not about using the latest technologies like the synthesizer back then or artificial intelligence today, but it’s about thinking about the life of all beings on our planet.

Isao Tomita and I talked a lot about reality and virtuality at the end of his career, and that reality can be recreated by electronic sounds, for example. He wanted to make Moog synthesizer speak, only elaborated on the synthesis of PaPiPuPePo sound in the seventies, but from there he continued the project underground until the appearance of Hatsune Miku. We also discussed why traditional Japanese puppet theater, the Ningyō jōruri, has been so successful in our country and why we feel empathy and emotion when watching puppetry. Isao Tomita commented at the time that perhaps that is what art is – that unnaturalness itself is art, and if we can combine this with nature, that will eventually allow us to be great.

So art is artificial, created by humans, with technologies created by humans. But technology changes over time, much like a season comes and passes. To feel this season, but at the same time to understand the earth and the universe, and to have a diverse view of nature with technology, I think that was a very important point for Isao Tomitas world.

Isao Tomita and Naohiro Ukawa

You have met Isao Tomita several times in person, what advice do you think he would give to young artists?

Naohiro Ukawa: I think his advice to the younger generation was to become an “otaku”. The word may not be used as much anymore, but in the 1970s there were people who stayed at home, locked themselves away and created something, although at the time it was considered cooler to be in a band. It’s mostly about the initial passion to create something.

I think the reason why punk music became so popular and widespread at the time was that you could form a band the day you bought your own instrument, even though you couldn’t play yet.That wasn’t the case with the synthesizer – it was harder to make sounds with it, there were hardly any manuals for it and you had to figure everything out yourself. This is also the result of the same DIY spirit as punk.

Nowadays we have a lot of apps on the internet that you can use to create music. There are many tools today that you can use to live out your passion. And I think Isao Tomita was a pioneer who opened up this world for us. And in doing so, he shortened the path for us from the initial idea to artistic realization.

“He said himself that you have to immerse yourself. Just like he did in his studio back then. Maybe it took him a whole day to create just one sound of a flute, maybe he fell asleep and then took another day to figure out what a violin sounds like. He immersed himself in this creative world to create his work of art. And I think that’s also the advice he would give to young artists.”

Gerfried Stocker: What we have to appreciate most about Isao Tomita is that he showed us as artists that we have to work hard to create this universe, to create this unity between us humans and our environment. Taking care of our world, of our planet, is definitely one of the messages he gave us, and definitely one of the great challenges for the artists of the future.

Naohiro Ukawa: Omni-directional artist known for extremely wide range of activities as a graphic designer, video artist, music video director, VJ, writer, college professor and “Genzai” artist among others. In March 2010, Ukawa founded a live streaming channel “DOMMUNE” which immediately attracted record-setting number of viewers for its daily programs very much discussed inside and outside Japan. In 2010, Ukawa received Agency for Cultural Affairs’ Japan Media Arts Festival Jury Selection for DOMMUNE as his very own form of art. 2021, he received the Minister of Education Award for fine Arts.

Gerfried Stocker is a media artist and an engineer for communication technology and has been artistic director and co-CEO of Ars Electronica since 1995. In 1995/96 he developed the exhibition strategies of the Ars Electronica Center with a small team of artists and technicians and was responsible for the setup and establishment of Ars Electronica’s own R & D facility, the Ars Electronica Futurelab. He has overseen the development of the program for international Ars Electronica exhibitions since 2004, the planning and the revamping of the contents for the Ars Electronica Center, which was enlarged in 2009, since 2005; the expansion of the Ars Electronica Festival since 2015; and the extensive overhaul of Ars Electronica Center’s contents and interior design in 2019. Stocker is a consultant for numerous companies and institutions in the field of creativity and innovation management and is active as a guest lecturer at international conferences and universities. In 2019 he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Aalto University, Finland.

Many thanks to Emiko Ogawa for organizing the interview and to Yoko Shimizu for simultaneous translation. The text was edited and shortened by Martin Hieslmair.