Researchers recently discovered, among the planets orbiting Proxima Centauri, an Earth-like body that could possibly sustain life. This is the first time that scientists have found such an exoplanet so close to our solar system. Proxima Centauri, only 4.24 light years (about 40 trillion kilometers) away, is the closest star to our Sun. The planet was discovered by the telescopes of the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile.

“I always had a very clear picture in my mind that astronomers were full of enthusiasm as they went about conducting their search for these Earth-like planets. But I thought that the enthusiasm was confined to the discovery itself and less to the speculative possibilities—like the discovery of life—that such an exoplanet might portend. After all, the only things that are actually known about these planets are their size, their location and how long they take to orbit their star. Otherwise, usually very little! It could just as easily be a dead planet like Mars. But the astronomers are just as emotional as the general public when it comes to this subject. And that truly did surprise us,” said Juliane Götz, a member of the artists collective Quadrature.

In this interview with Sebastian Neitsch, Juliane Götz and Jan Bernstein, the three members of Quadrature talk about the impressions they got during their art & science residency at the ESO in Chile, and about the works of art that have emerged from this stay and will be presented at the 2016 Ars Electronica Festival.

“Quadrature”: Juliane Götz, Sebastian Neitsch, Jan Bernstein. Credit: Quadrature

So let’s get right to the point: How did it go during your residency at the ESO locations in Chile?

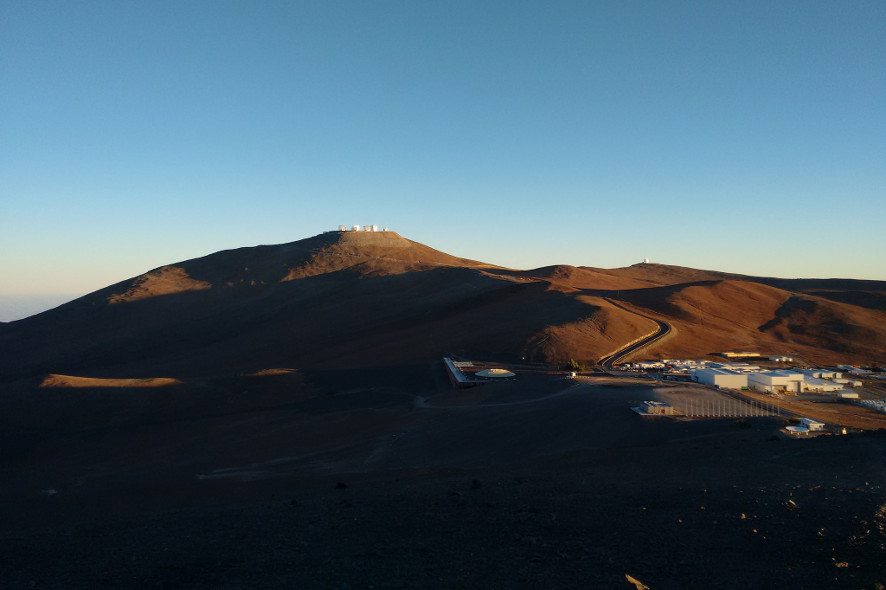

Sebastian Neitsch: Everything came across as rather absurd. The landscape is absurd, the architecture is absurd, the technology is absurd—but in a positive sense. And it all seems so utterly absolute. The landscape is absolutely arid. The architecture is absolutely functional and, nevertheless absolutely designed and aesthetic. The people, I’d say, aren’t necessarily as absurd as their workplace, but they’re absolutely concentrated and enthusiastic. That’s the world’s driest desert; there, it looks like you’re on Mars—appropriately enough. And then, on some totally remote location, on top of a mountain, in stark contrast to the surrounding landscape, there are these spearheads of modern technology. Very impressive.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

What did you experience there? Did you accomplish everything that you set out to do?

Juliane Götz: We got to pretty much every place we wanted to visit. For starters, we spent a few days in Santiago de Chile, where we toured the headquarters of the ESO and took part in a fascinating Q&A session with several astronomers. That was a really good intro, since it gave us highly detailed explanations of a wide range of subjects from the astronomers’ point of view.

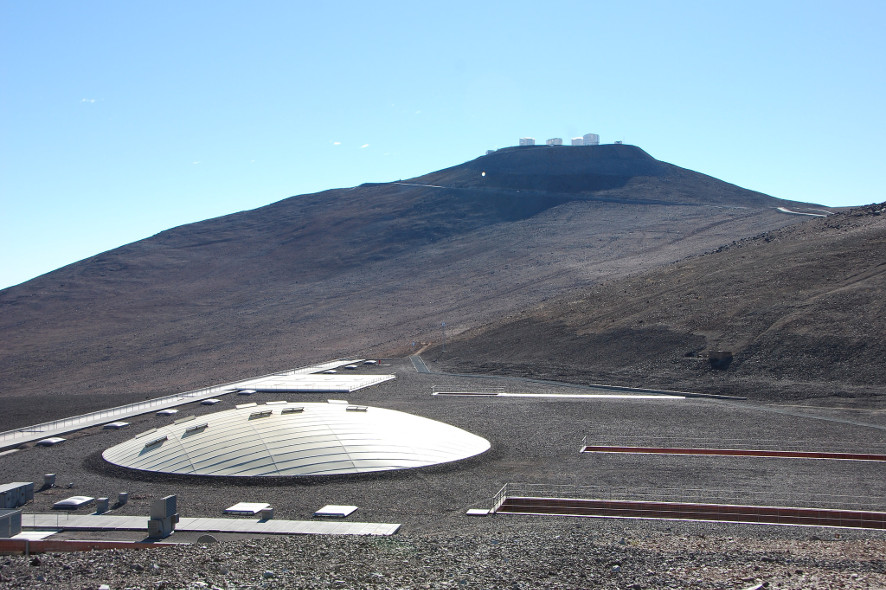

Then, we traveled into the Atacama Desert to the Paranal Observatory to inspect the VLTs (Very Large Telescopes) at an altitude of 2,500 meters. The opening rituals every evening and the calibration of the telescopes are what we found most impressive.

Credit: Sebastian Neitsch

Sebastian Neitsch: The ritual proceeds identically every evening. Imagine that you’re in the Ars Electronica Center and the part of the building you’re in remains stationary but the entire structure all around you starts to rotate—I mean, those are the dimensions we’re talking about here. So, like I said—absurd! And then the interior starts to turn too. It’s like when you’re sitting in a train stopped in a station and the train on the next track starts moving; you briefly get the feeling that you’re moving even though you’re standing still. Except this is on a much, much larger scale.

Juliane Götz: We also got to see the underground VLTI Delay Lines. This is a huge interferometer in which the four telescopes can be interconnected. But since the telescopes are all located at a different distance from the interferometer, the light has to queue up, so to speak, so all the rays arrive simultaneously at the instrument, right down to the micrometer. This is a 160-meter-long hall that’s set up with four systems of tracks on which the light can be shuttled back and forth.

It was also really fascinating to see the control room there on site when the astronomers were actually performing their observations, and to see the raw, still-unprocessed recordings live, and to experience the mood. This is what enables you to understand all the work that goes into these findings and the finished, high-resolution images the general public gets to see.

After almost a week in Paranal, we moved on to ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array), an arrangement of 66 gigantic radio telescopes set up at an altitude of about 5,000 meters. This was even more absurd than our first stop. It was like being on another planet. We had to undergo health checks and each of us was issued a small oxygen tank in case of emergency.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

What were you able to derive from these experiences and take with you to the Ars Electronica Futurelab, the location of the second part of your art & science residency?

Sebastian Neitsch: First off, the fact of how little all these very clever scientists actually know! For example, it’s not yet been proven once and for all that we have only one Sun in our solar system. I found this very interesting. Of course, it’s highly probable that there’s only one Sun, but it’s certainly odd that this isn’t a 100% certainty!

We didn’t realize that these high-tech machines constantly have to be calibrated and repaired. That’s completely normal and part of the daily routine. In Paranal, almost 100 people are constantly at work keeping these machines up and running. This is the ultimate technology that humankind is capable of constructing at the moment in this field; all of them are custom-made instruments. We were utterly astounded by the relationship between the actual use of these machines and their calibration. It’s like more time is spent working on the machines than with them. The telescopes are very sensitive. When it’s too windy or cloudy or there’s too much dust in the air, the astronomers can’t observe.

Quadrature and Fernando Comerón, the ESO’s man in Chile (Credit: Claudia Schnugg)

Juliane Götz: After all, these facilities are set up so far away from civilization amidst the world’s most arid desert, but the disruptive element is nature itself, the very thing that’s meant to be observed!

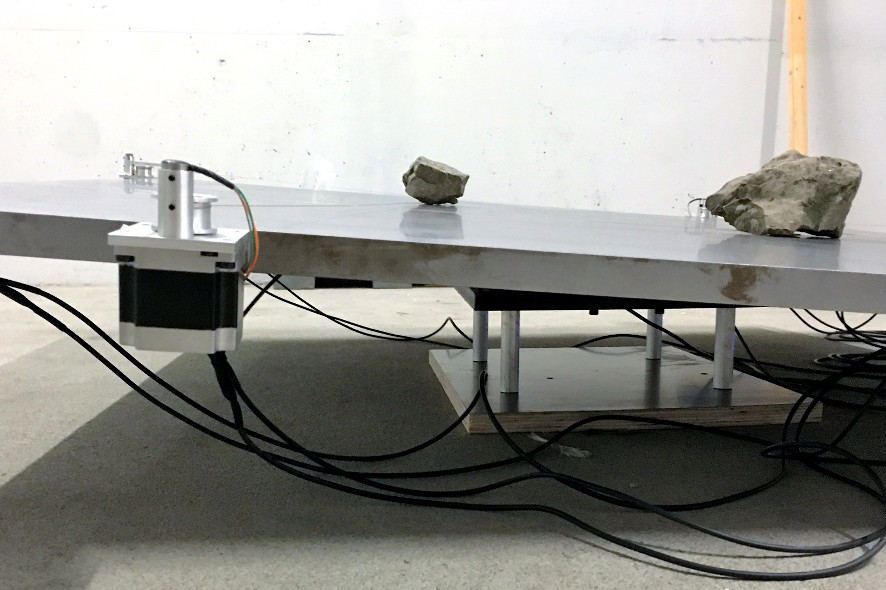

Sebastian Neitsch: It takes a huge effort to keep this gigantic thing running the whole time, and this engendered one of the ideas that we aim to realize in the form of an artistic work—this equilibrium between calibration and function. The balance between technology and environment has to be sought and discovered repeatedly. Astronomers in general often speak of equilibrium. For instance, if the relation between gravitation and centrifugal force in our solar system got out of whack, everything would fly apart or smash together. And even this equilibrium isn’t set for eternity; the slightest fluctuations are all it would take to destroy the prevailing order of things.

Could you tell us something more about this project that will premiere at Ars Electronica 2016?

Juliane Götz: We’ve entitled it “MASSES,” which stand for Motors and Stones Searching Equilibrium State. The work consists of a 1.2×1.2-meter steel plate that attempts to achieve balance. The plate is freely positioned so it can tilt in any direction. Lying upon the plate are two volcanic stones that can shift their position in such a way that the plate briefly maintains equilibrium. Our hypothesis is that it will never be possible for this plate to remain in balance for long; it will incessantly tip in some direction. The machine is constantly busy calibrating itself in order to attain the perfect state of balance. It never achieves it totally, but it never becomes completely unbalanced either.

During the preparation of MASSES (Credit: Quadrature)

You’ll also be presenting a second work at POSTCITY…

Sebastian Neitsch: The second work is entitled “STONES,” which stands for Storage Technology for Observed Nearby Extraterrestrial Shelters. It’s a new storage technology for information about exoplanets in the so-called habitable zone.

Juliane Götz: The search for exoplanets is currently a very exciting field of astronomy, and has been attracting tremendous public attention. An exoplanet is one outside of our solar system. It’s assumed that most stars have at least one planet in their orbit. If such a planet is the right distance away from its star so that it’s not too hot and not too cold and water could theoretically exist in a fluid state on its surface, then it’s in the habitable zone. In this solar system, Earth—obviously—and Mars—barely—are in this zone.

Sebastian Neitsch: If we were to eventually discover another planet somewhere that was like Mars, we would all get totally worked up and it would probably be a hot prospect to become a second Earth. But Mars is a dead planet without a protective magnetic field and with a very thin atmosphere. But we wouldn’t necessarily know that if Mars were further away and there’s even a slight possibility that the planet could host life. This possibility alone and the fantastic images and narratives engendered by it and coupled with modern pop culture create lots of emotions as soon as a new planet in the habitable zone is discovered. We’re really fascinated by this ambivalence between purely objective scientific findings and public perceptions.

Juliane Götz: In our project, we wanted to depict only pure information—without any sort of cultural interpretations—and to store it for future generations. Up to now, the data have been stored on SSD hard drives that are fast but, in comparison to the planets, very short-lived.

Sebastian Neitsch: We, however, wanted to store the data on a medium to which data can be input only very slowly and has very little storage capacity, but the stored data is retained much longer. We write the information in the form of a binary code imprinted into granite that, if it’s stored properly, is extremely durable.

Our message preserved for eternity on stone slabs is a sort of signpost in the heavens should future generations want to—or have to—leave planet Earth. The pure information is meant to be legible by anyone who finds it in the future, which is why we use the language of mathematics. It’s the same throughout the universe. This approach is comparable to the one taken with the famous message on the Voyager space probe, in which the attempt was made to formulate everything conveyed about humankind in such a way that no prior knowledge of human culture would be necessary to comprehend it. That means that you don’t have to understand a particular language in order to read it. All you need to know are the basic physics of how the universe functions and you have to be conversant in the universal language of mathematics in which 1 + 1 = 2 everywhere. Then, you’re hopefully in a position to read this.

Furthermore, we were interested in the commonalities shared by astronomy and religions. These giant telescopes have been erected in the most remote locations, mostly on mountaintops like many temples, monasteries and churches have been. You’re very close to heaven. Up there, scientists are working with their language of mathematics that’s barely comprehensible by the “common folk” and they’re explaining the world to us a little like the way priests used to do. Priests often used their own language and explained the will of God to the people living down below in the valley.

Credit: Martin Hieslmair

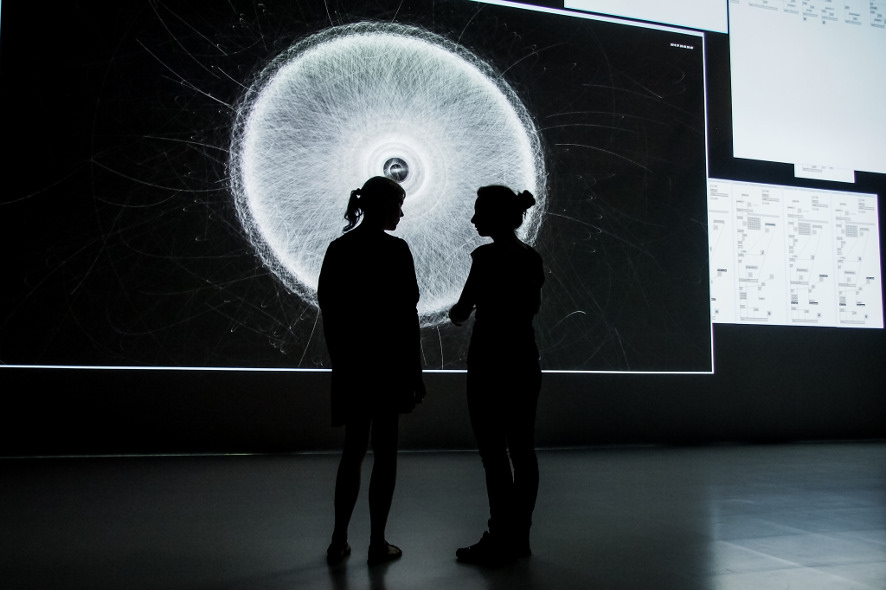

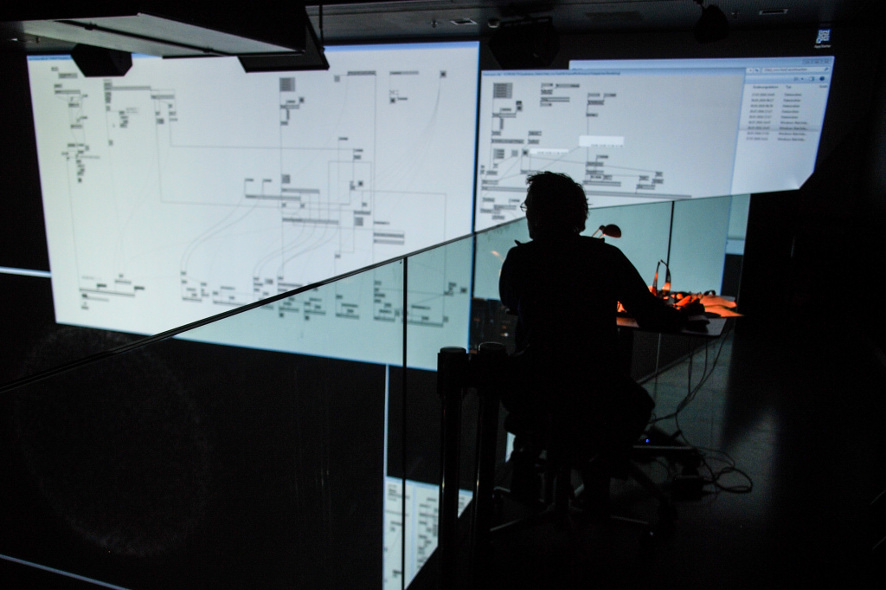

At the 2016 Ars Electronica Festival, you’ll also be presenting an audiovisual performance entitled “Orbits” in Deep Space 8K. Could you tell us a little more about this?

Juliane Götz: “Orbits” is the spinoff of a project in which we followed the movements of satellites in real time. That was exhibited at the Ars Electronica Festival last year. But we don’t only show these 1,500 satellites from last year anymore; in the meantime, we’ve added space junk and unofficial objects like espionage satellites. The total number of objects exceeds 15,000.

This work isn’t a video; it runs in real time. We start in the here and now. That means, you have a view of Linz and you see all the satellites within a radius of 100 kilometers. The number of satellites you can see depends on the current traffic situation—sometimes more, sometimes less. Each satellite that flies across the screen produces a minimalist tone—a sine wave whose frequency depends on its altitude above the surface of the Earth and whose volume depends on its distance from the observer. As soon as several satellites are being “tracked,” this results in complex soundscape that can sometimes be a bit painful to listen to.

Then we slowly zoom out to Linz and speed up the time lapse. You get an increasingly greater impression of the sheer mass of objects, until the virtual camera finally remains stationary approximately 55,000 kilometers away from our planet. We never show the Earth itself, but you recognize it in terms of the parts that are orbiting it. This evokes what might partially be described as a pretty kitschy aesthetic. Floral, organic patterns that are made to appear so magnificent out of pure physical necessity, but also the hunks of space junk produced by our civilization.

Credit: Martin Hieslmair

Quadrature

Jan Bernstein, Juliane Götz and Sebastien Neitsch met at Burg Giebichenstein University of Art and Design in Halle, Germany. After completing their education, the artists worked individually in, among other cities, Antwerp, Linz, Valencia, Vienna and Stuttgart. They collaborated for the first time in 2000, and went on to establish Quadrature, a collective in which each member inputs his/her own specific skills and focal-point themes. Most of their artistic projects focus on the contradiction between knowledge and comprehension.

During the Ars Electronica Festival, September 8-12, 2016, the works “MASSES” and “STONES” will be exhibited at the POSTCITY, the former postal service’s letter & parcel distribution center of Linz. “Orbits” will be performed several times a day during the Festival at Deep Space 8K at the Ars Electronica Center. Here you find the exact dates and times: https://ars.electronica.art/radicalatoms/en/deep-space-8k-orbits/