Everything has been new at the Ars Electronica Center since May 27. One topic that can be found everywhere is Artificial Intelligence – content that is not always easy to convey, whether to children, adolescents or adults. So it’s a good thing that there are professionals with professional, human and humorous expertise. We spoke with Nicole Grüneis, Head of Education and Cultural Mediation, and Katharina Hof, her colleague.

How do you arrange the mediation for children and young people? How do you introduce the topic of artificial intelligence? And to what extent does this approach differ from that of adults?

Nicole Grüneis: The human-machine-analogy is a very helpful one, also concerning the understanding of programming and computer systems in general. We anyway tend to start from our own experiences. We pick that up and compare the living being human being with the being of the machine in general, e.g. by asking what kind of senses machines can have. So while machinoid systems are equated with the system of the living, children have a good understanding. Of course this also works with adults, but with children it is much more exciting, because animism is still part of the childlike world view. A child can imagine something with character and life traits quickly and vividly. This has always worked quite well for us in technology mediation, but now this analogy is also played through within the exhibition, which makes mediation concepts and exhibition strategies grow even closer together.

The workshop on Artificial Intelligence for primary school children starts with the question of how to control machines. You quickly end up with programming. And then we ask them if they think they themselves are programmed. They most likely answer no. But when you call their name, they react instinctively. This means that very small and subtle interventions to get you started quickly arouse the interest of children. If we explain the functioning of an AI, we work out the independent learning in contrast to programming. Again, we link this to their own learning processes: what they learned last, how often they had to repeat it, whether they’ve taught someone else or trained their pet. It is always a matter of immediate referencing to oneself or to beings known to them.

This also works for adults, but the interest is more likely to come when you quickly get into applications. The theoretical approach is bottom up versus top down. Children start with very simple explanations and then the complexity increases. For adults, there is a complex initial concept from which “breaking down” is done to simple applications. This can be explained by the fact that adults already have a picture on the subject – that doesn’t have to be elaborate knowledge or a thoughtful opinion, but a picture is already there. With children, on the other hand, worldviews and values are much more sketchy and thus more dynamic in their expansion and adaptation.

Credit: vog.photo

Is there anything easier for children than for adults?

Nicole Grüneis: Try it. They lack this false, acquired respect and therefore they simply dare to lend a hand. They are also not afraid to fail or to do something wrong. Children don’t care.

Which new installations work best for children? And why?

Nicole Grüneis: The puppet robot “pinocchio” is very popular – the puppet theatre setting, the story behind it. So many factors come together in this installation that trigger fascination: The robot that moves the puppets, i.e. holds the threads in its hand, and the human being that is replaced by a carved puppet. The fear of humans to be replaced by robots or to become a play ball of uncontrollable powers is very easy to grasp in this packaging for children, but also for adults, and they enter into an abstract level of thought. We observe their reactions, they are captivated, fascinated, the attention is totally there. And a momentum of reflection. At least for a short moment…

Credit: Ars Electronica / Martin Hieslmair

You’ve developed a children’s book. How did this come?

Katharina Hof: The initial idea came from Ulrike Mair, an infotrainer, and then it became a project of the infotrainers of the Ars Electronica Center, in which many contributed their expertise. All those who wanted to worked together on the wonderful facing paper – it looks like a wallpaper or letterhead made up of individually designed water drops. The water drop symbolizes the initial spark for the “reawakening” of the protagonist. (More on this later.)

The structure of the book is divided into two parts – on the one hand there is the continuous story, on the other the excursus. The excursus is always to the right of the story and explains the sometimes quite complex topics and concepts exactly where they occur. The target group is children from about four years of age for the adventure story, from about seven years for the explanatory excursions. But the book is certainly also interesting for adults.

Nicole Grüneis: But it’s not “just” a children’s book in which the protagonist experiences the most diverse and unusual adventures, there’s also a certain attitude towards values that we want to transport along with the story. And that’s: Stay open for unusual encounters and different characters confronting you. Be amazed and fascinated!

Tardi, the tardigrade Credit: Nini Spagl

Tell us a little about the story. And of course about the protagonist!

Katharina Hof: The protagonist of the children’s book is Tardi and Tardi is a tardigrade.

Tardigrades are very small creatures, maximum 1mm in size and invisible to the naked eye. They can be found almost everywhere outside. They prefer to live in humid areas like water or moss. They are cosmopolitans and at home all over the world, even in the most impossible places. You could even cook them for a few minutes in a saucepan and they would survive. They have also been exposed to the vacuum in space and survived. This is because the tardigrades have a very special ability: cryptobiosis.

In cryptobiosis, the tardigrade retracts its arms and legs and becomes a kind of ball or barrel. In the barrel stage, the entire metabolism of the animal is completely reduced and puts it into a kind of suspended animation. However, it can also very easily be brought back to life – if it dries out, for example, a drop of water is enough to revive it. The total survival artist.

In the new bio laboratory there are microscopy workshops, where people go outside and collect data in order to observe and analyse them in the laboratory. Tardi is found at such a workshop with children outside on the Danube and discovered under the microscope. And he escapes.

As he then taps from one place to another in the Ars Electronica Center, he encounters the themes of the new exhibition.

For example, he encounters the “Muckileins”, the muscle strands from the installation with precursor cells of rats and mice. Or he drives a round in the Connectrom, the Open Worm course with a kind of Autodrom car. But he doesn’t even have to steer himself, because the worm does this on its own and that’s why Tardi can stretch a few of his eight legs into the air – just like the brave ones on the roller coaster. In addition to the fairground autodrome, the Connectrom also alludes to the connectome – the entirety of the connections in a nervous system. On his further discovery tour, Tardi enters the Circus Robotica, where the marionette robot makes the puppets dance so wonderfully. He also meets SEER, the small robot head that masters the mirror trick and can imitate all facial expressions.

The meeting of Tardi with “the” AI is also exciting, because there is no artificial intelligence. Rather, it can have many different manifestations – language assistants, crime prediction tools, self-propelled cars, mobile phones, and much more. However, this diverse form of representation should not be mystified as if the AI were a spirit or a monster or any other magical being. And so we have decided to turn this meeting upside down and show it from the perspective of the AI. So Tardi meets the AI and is recognized wrong for the time being – as a nut. Or maybe he is a caterpillar after all?

Nicole Grüneis: A tardigrade is simply not yet in the artificial intelligence data set and therefore cannot be detected. In the end, however, it is included in the AI repertoire.

Katharina Hof: At the end of his journey, Tardi discovers a large moss wall in the children’s research laboratory and moves in there. If you’re very skilled with the microscope, you can find Tardi there, but definitely his friends.

Credit: Ars Electronica / Robert Bauernhansl

We have now landed at the new children’s research laboratory, which will inspire young and old from 24 June. What will there be to see?

Nicole Grüneis: At the back there will be the moss wall. It consists of cultivated and prepared moss, in which we will probably not find any living beings outside the book. For this there are glass containers with freshly collected moss, quasi small moss terrariums, where the microscopic life can be explored.

Katharina Hof: Here you will find repeated illustrations from the book. Tardi is therefore also present here and refers to the basic task of the children’s research laboratory: making things visible with technology.

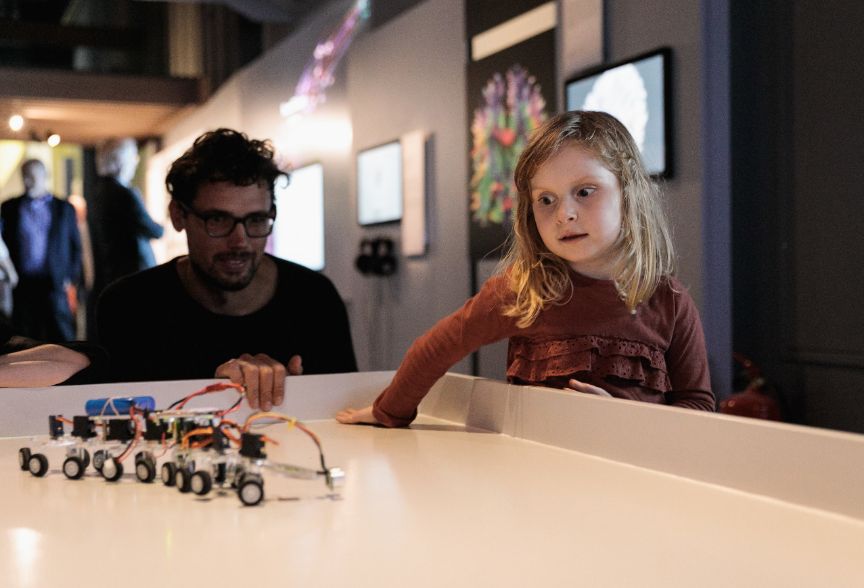

Nicole Grüneis: There are many more great applications here: In the “Animaker”, children use duplo bricks to build animals that are recognized by an AI, transformed into a cartoon animal and projected onto the wall. In the “Sandbox” the projection changes according to the formation of the sand. Composing is done at the music table, making an invisible image visible in “Non Visual Art”. On the bridge at the robot playground little robots are scurrying around, drawing or following strokes or playing music and much more. Many different interactions with machines can be tried out here.

The exhibition Mirages & miracles can be admired on the first floor, where an augmented dimension is added to the objects and drawings by means of tablets or VR glasses. In the future, an extended animated layer for Tardi, the tardigrade, would be an excellent idea!

Katharina Hof (left) & Nicole Grüneis, Credit: Ars Electronica / Martin Hieslmair