What happens to television content when the resolution of our screens gets higher and higher? How can we interact with larger displays? And what new media formats will be possible with 8K or more? These are questions that the Japanese broadcasting corporation NHK and the Ars Electronica Futurelab have been asking themselves for several years now. In their joint research “Beyond the Frame“, they have been exploring possible answers since 2015.

At the 2019 Ars Electronica Festival (5 – 9 September), several prototypes will be presented. We spoke with Roland Haring and Nicolas Naveau from the Ars Electronica Futurelab and found out more about the project, the research questions and the future development of television.

We have heard about Beyond the Frame at last year’s festival already. Roland, could you explain the developments so far?

Roland Haring: NHK, a Japanese broadcasting company, started working on 8K television technology a few years ago. They were the first to do this in the world, complete pioneers. In principle, Japan simply skipped 4K and focused directly on 8K! The background is that the Olympic Games will take place in Tokyo in 2020 and Japan would like to broadcast the events in 8K. NHK is not only driving these developments for the Japanese market, but also sees them as a unique selling point for the Japanese entertainment and electronics industry.

It was through NHK interest in 8K that they first made contact with us, the Ars Electronica Futurelab – we opened Deep Space 8K in Linz in 2015 and began our first cooperation with NHK. They provided us with very early, experimental 8K films so that we could show them in the new Deep Space 8K. That was a great challenge for us from the beginning, 8K video technology was not commonly in use yet and we not only had to replace the projectors so we could project a higher resolution, but we also had to make sure that the content was playable.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

Wasn’t Deep Space 8K created for exactly this kind of content?

Roland Haring: No, because there are different types of content. You can produce 8K, but you have different ways of projecting the image. This can happen via real-time graphics, with a 3D engine that calculates the image, or as video. With every option you have a different image structure, different options for the images per second, and much more. In 2015 we were able to play 6K video very well at 60 fps, which was sufficient for our purposes. In addition, we hardly had any content that had a higher resolution than 4K. As part of our European research project Immersify, however, we worked very hard on this and integrated new video codecs that allow much higher resolutions.

One consequence of this, if you increase the resolution in this way, is that you can make the screens bigger. After all, the question is: What is 8K actually useful for? When I think of my little TV at home, HD is enough – even if I had 4K or 8K, I probably wouldn’t notice the difference. But the displays are generally getting bigger and with increasing dimensions the higher resolution makes sense. This is also true for us at Deep Space 8K.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

What are the consequences of these large displays for the content?

Roland Haring: We’ve found that it’s not effective to simply display existing content in a higher resolution. Once a certain size is reached, image composition no longer makes sense. This has always been the case for us at Deep Space 8K, for example when we had video conferences and the webcam image suddenly showed a seven-meter-high head! This completely changes the effect of the image. So you have to rethink the composition of the image and the way you work with the surface of the screen. This is actually only possible by thinking about new content, new forms of staging, new ways of representing people.

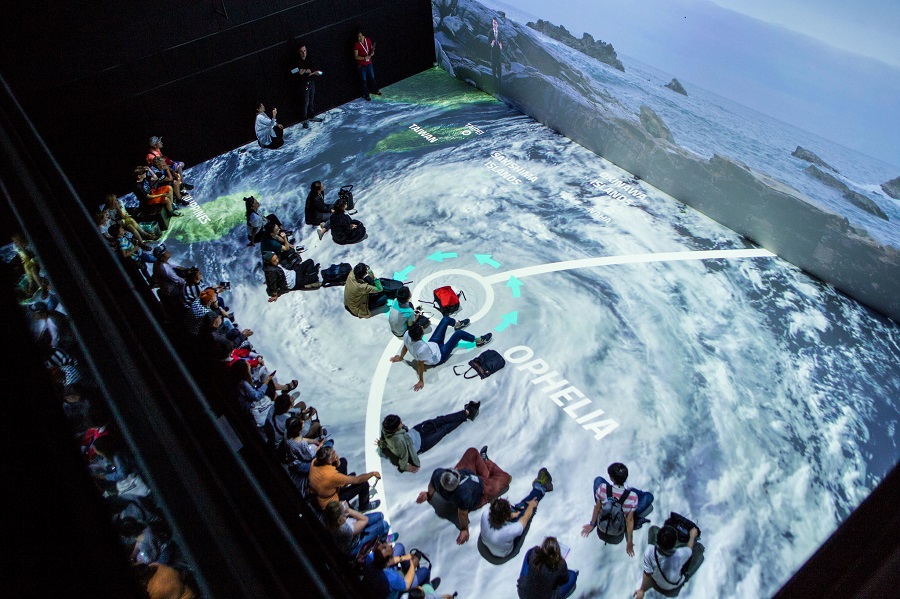

Nicolas Naveau: We tried this out with NHK in two phases. In phase one, we wanted to redefine the image or language for such large screens and think about new types of television. We also researched how to integrate the ambience or work with media architecture. One idea at the time had to do with scaling: For example, we took a weather forecast and wanted to adapt it to the new screen size. We had the idea of displaying things as big as they are in real life – one to one. That’s a concept we’re continuing now, in phase two.

In the case of the weather forecast, this means that the moderator is really as big as in real life. In our fictional scenario, a typhoon approaches Japan and the forecast explains what the people in Japan should expect. The report takes place from a coast, the stones are as big as in real life, the coast as high and the sea as big. In addition, we show infographics in which you can see in real size how many centimeters of rain will fall, how big the waves will be and how fast the wind will blow. It’s something else to simply say that there’s a seven-meter wave coming, or really displaying it in the size of seven meters! Also with the wind speed you get a very good feeling for what this really means. The weather forecast becomes a physical experience. As I said, the project originates from Phase One and was further developed later, now we’re showing it at the Ars Electronica Festival 2019.

Credit: Magdalena Sick-Leitner

But Beyond the Frame isn’t just about adapting content, it’s about thinking outside the frame completely.

Roland Haring: Right. We want to find new formats that become possible or meaningful with 8K. At the beginning of the year we realized a second prototype….

Nicolas Naveau: …the Mobile Media Platz. A small version can also be seen at the festival, in the Open Futurelab at POSTCITY. It’s a mobile screening place for 8K content. The prototype we show consists of cardboard furniture from PappLab. The idea behind it is to invite artists, designers, and other creative people to design this space so that it becomes transformable. Each kind of content gets its own kind of space. We could design a place for an animation festival, but also for a workshop or a catastrophe situation. For example, if a typhoon really happened in Japan, the Mobile Media Platz could be set up in a gym and offer emergency power, blankets and candles as well as important information. At an animation festival you could instead write on the media furniture with chalk, comment or vote on films.

But the main focus this year is on the Deep Space 8K projects?

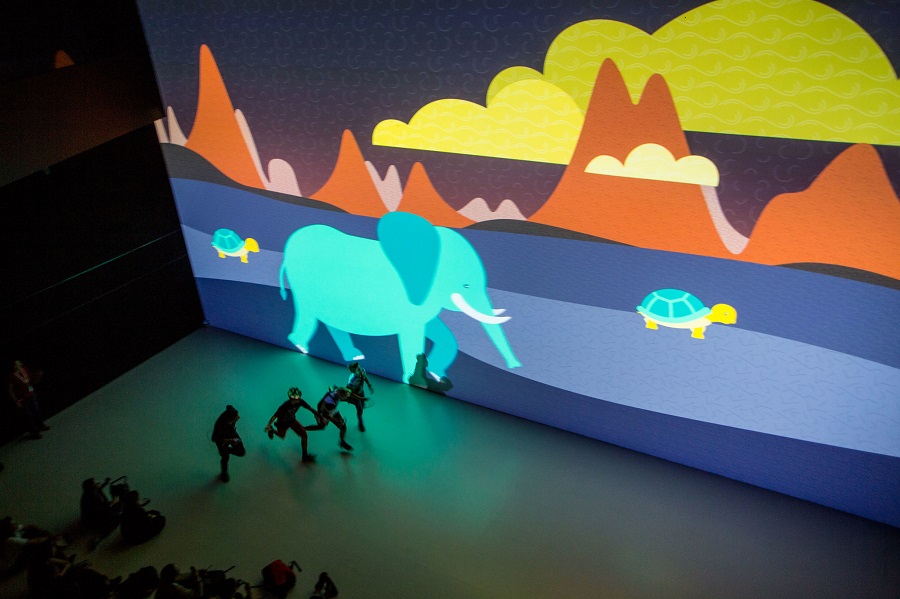

Nicolas Naveau: We are continuing the concept of life-scale with an animated film for children. We have made small films of three minutes each, which represent the beginning of an educational series. The films explore the world by comparing size and height: A child is as tall as a lion, five lions are as big as a giraffe, a giraffe eats so many kilos of leaves a day, that’s so many apples, and so on. You can see how big these animals or things are in real life. The end of each film is fluently blended into the next, and we’ve also built in participative elements. For example, children can run alongside an animal to compare speeds.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

In addition to the Life-Scale Weather Program and the Life-Scale Kid’s Program, an art film will also be shown. What is it about?

Roland Haring: It’s a production by NHK, a stereoscopic film that is based on the story of Alice in Wonderland, but is set in Japan today. The film was produced as an 8K stereoscopic film that can be viewed with 3D glasses, but also contains a second image layer that is created in real time. This allows you to contribute to the film yourself: The position of the people in the room is tracked; depending on where you stand, you create three-dimensional objects in the film. In a scene, for example, bubbles are created. It’s very exciting: how can you think more interactively about the medium of video? How does movement in front of a large screen change the content? At the moment it’s a prototype, but you can already see where it’s going in the future.

Nicolas Naveau: What I think is cool is that you don’t just choose between two options, but the interaction really influences the content. You create bubbles in a world where you stand. That’s very immersive.

Roland Haring: In all these areas I find it exciting that attempts are made to develop the medium of video itself. The medium is decades old in terms of its basic conceptual structure; at most, its resolution is improved. It is very difficult to change it more because the entire television broadcasting infrastructure is attached to it. However, streaming portals such as Netflix or Amazon are currently undergoing a rethink. Classic television no longer has a monopoly; every content provider can design very freely. This opens up a new playing field for interactive media formats in the medium term.

Credit: Vanessa Graf

Where do you think the development is heading?

Nicolas Naveau: Scaling is definitely a big issue. At Beyond the Frame, we also want to consider when it makes sense to change the image content at all – how big does the display really have to be? That’s something that’s very relevant to content production.

Roland Haring: You have a lot of flexibility in content production, each element can be arranged differently. At some point, however, the content is rendered and becomes frozen, unchangeable, so to speak. It has a certain scaling that is fixed and in which the content is transferred and displayed. It would be exciting to maintain the flexibility of scaling until the moment the content is actually presented. You could compose and arrange the image very dynamically depending on the screen.

Nicolas Naveau: With smartphones, the big revolution here was the responsive design, in principle it’s very similar now. It would be Responsive Design for screens. Another topic that we haven’t covered yet is sound. If you open the room with big screens, you get a lot of new possibilities with sound. Something that would also interest us would be that content changes according to the audience’s attention. Content could change its size when you look at it or get closer to it. The question of whether a device is needed for interaction or eye contact is also important here.

Roland Haring studied Media Technology and Design at Hagenberg University of Applied Sciences. Since 2003 he has been a member of the Ars Electronica Futurelab and one of the driving forces behind the lab’s R&D efforts. His activities include research and development in several large R&D projects with academic, artistic and commercial partners and collaborators. Currently Roland Haring is the Technical Director of Ars Electronica Futurelab and co-responsible for its general management, content conception and technical development. With his many years of experience in the (software) technical management of large-scale, research-intensive projects, he is an expert in the design, architecture and development of interactive applications.

Nicolas Naveau graduated at the Fine Arts School of Angers, France (Master of Arts). He went then to Vienna (Austria) where he taught French Culture (Art History, Comic and Cinema) in a Adult educational School. Due to his knowledge and skills in Art, Graphic- and Information-Design, he started to work for Ars Electronica Linz in 2002. Since 2006 he works for the Ars Electronica Futurelab as Artist and Senior Researcher in the field of Information Design.

At the Ars Electronica Festival 2019, Beyond the Frame: Future Project will be shown at Deep Space 8K. In the Open Futurelab in POSTCITY Linz you can also take a look at the Mobile Media Platz. More information can be found on our program website!

To learn more about Ars Electronica, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter, and check us out online at https://ars.electronica.art/news/en/.