Here we go again! Students in the Time-Based and Interactive Media Arts bachelor’s degree program at the Linz University of the Arts will be presenting their projects at the Ars Electronica Center. The Linz University of Art and Ars Electronica have had a close relationship for many years. As part of the TIME OUT exhibition series, the Ars Electronica Center provides young media artists with space for their work.Whether it’s film, sound, programming or interface technology, the “Time-Based and Interactive Media” course of study gives its students plenty of freedom to express themselves creatively. The resulting works are as varied as the course itself – a selection of which will be presented at the Ars Electronica Center starting April 6, 2022, under the title “TIME OUT .10.” This year’s focus is primarily on interactive works for Deep Space 8K, as well as the floor of the AEC lift. In this interview, Director of Studies Gerhard Funk tells us more about the students’ works, the concept of cooperative aesthetics, and gives an outlook on the upcoming edition taking place this summer.

The Time Out exhibition series was launched in 2012 to give students in the “Time-Based and Interactive Media Art” field of study an opportunity and a chance to present their work to a broad public at the Ars Electronica Center. Can you explain the field of study a bit?

Gerhard Funk: Time-based are all artistic directions where the time factor is a design element. That is, when it is a matter of designing temporal sequences or developing a dramaturgy. Video is clearly time-based and audio is also clearly time-based. At the time, we deliberately decided against calling this field of study anything to do with video, because we wanted to make it more general. It comes from the history from the audiovisual diploma program from the 90s. On the one hand, it’s about film production, cinematic works, definitely in the classic narrative short film, experimental film and video installations. The whole thing is expanded by the interaction component of interactive works, which was introduced in Linz very strongly by Ars Electronica. Our students receive a sound basic training in filmmaking, ranging from camera, script development, lighting design, sound, etc., expanded by interaction, which means that the users have the opportunity to influence the temporal course of a work. The field of interaction is also a broad one. It can be purely screen-based, i.e. one interacts with the computer screen via mouse and keyboard, but it is also very much about the development of interfaces. Students also get a foundation in programming, a required subject from the beginning, electronics, working with microcontrollers and soldering. All these basic skills you need to develop small interfaces yourself and then link them to a video work, for example. Often there is no screen at all as an output medium and you don’t feel that there is a computer hidden somewhere in the work when you interact with it. The goal for me is that at the end of the course the students know what they are interested in and what direction they want to go in.

At Time Out .10, 11 Cooperative Aesthetics projects will be presented for the Ars Electronica Center’s Deep Space. What exactly do you mean by the term “cooperative aesthetics”?

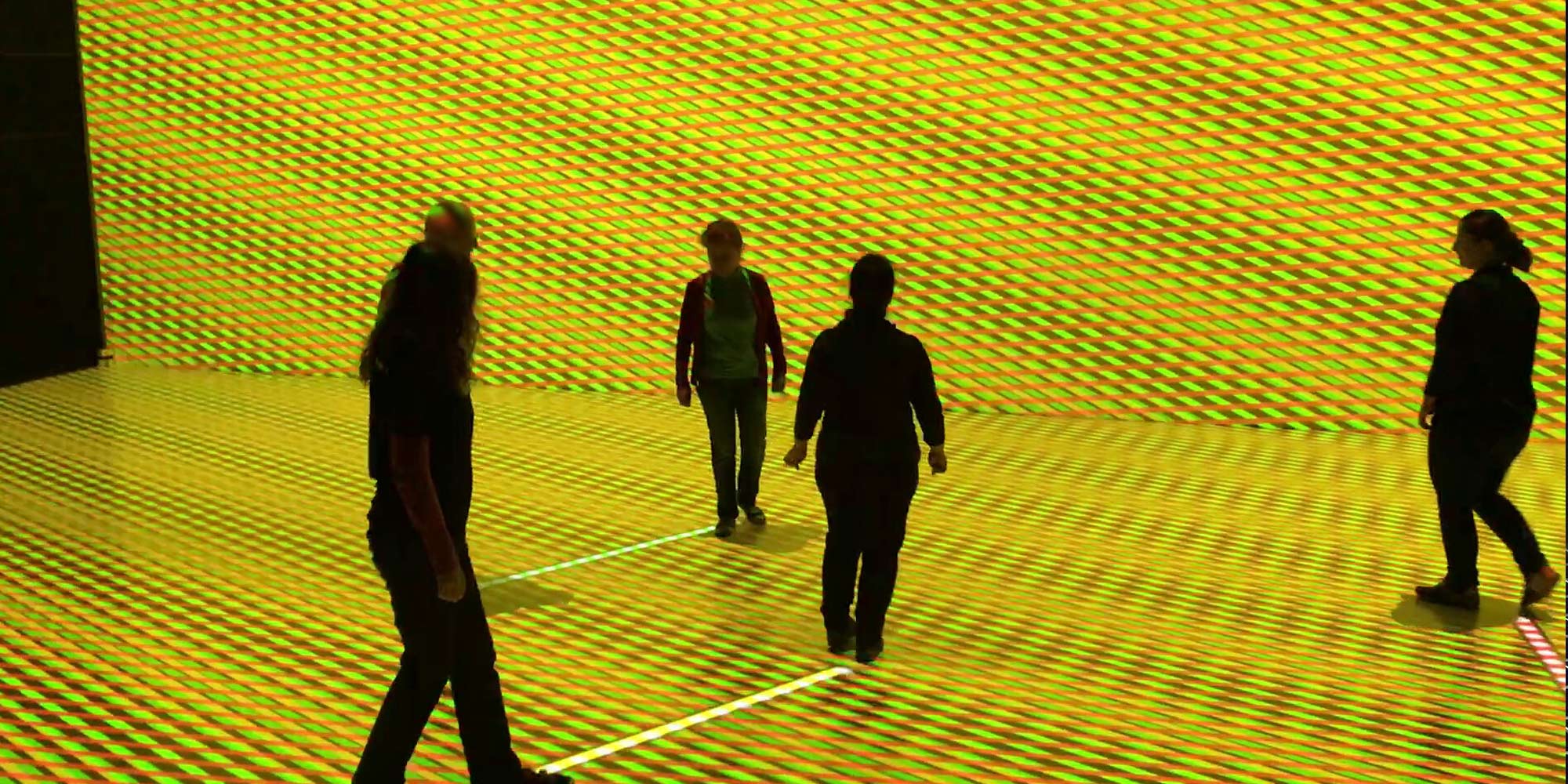

Gerhard Funk: For me, this term includes on the one hand a shared aesthetic experience of the users in Deep Space. That they interact with each other, interact and thus create an audiovisual experience in which they are completely enveloped in this space through the floor and wall projection, as well as the sound level. In addition to the aesthetic, this concept also includes a strong group dynamic, social component. The possibilities of Deep Space created in 2009 are wonderfully suited by the tracking system, because it is such a low-threshold imperceptible interface. You enter the space and you are already part of the whole and can interact with the space. It’s up to the people in the space what they do with it, whether they all walk around for themselves, or start communicating and coordinating their movements, that’s always been the goal for me in this series.

There will also be new videos for the lift in the Ars Electronica Center. What can we expect here?

Gerhard Funk: This elevator was already installed in the first Ars Electronica Center in 1996, and the floor projection that plays from below was a big attraction back then. A few years ago, Christoph Kremmer asked us if we wanted to do something new for the elevator. We took this as an opportunity to think about possible videos that could be influenced by the lift movement in our introductory course “Idea generation, conception” in the first semester. A lot of ideas emerged and after a selection of works that could realistically be implemented in the first semester, these were realized in the group. What we will see at TIME OUT .10 are works from two years, which unfortunately have been lying around for a long time due to Corona, since it was thought to present this exhibition already in 2020. You can expect very different works such as the work of Celina Altmann which forms a series of three works. In this series, a strawberry, blueberry and raspberry were each pressed down with a glass plate until they were completely crushed. When you ride through the elevator in the Ars Electronica Center, you can now recreate this process of crushing the fruit. Another work by Elena Richtsfeld shows her dog Bailey trying to get to a ball by bouncing. The projects are all very different and there is no clear line. Another exciting work is “Liftknopf” by Lisa Studener. In this work, the lift buttons were removed and the bacteria on them were evaluated in the Ars Electronica Center’s BioLab. So you can see the bacteria that are on the different surfaces in the elevator in a very big way.

Due to Corona, Time Out .10 is two years late. How has the pandemic affected the students’ work?

Gerhard Funk: The works that we are showing at TIME OUT .10 were all created beforehand. In the case of the Deep Space works, we had the opportunity to present them already at the festival, but only once. Some of the works have already been integrated into the current program, but we have decided to present them all together again outside of the festival.

The next Time Out is already taking place at the Ars Electronica Center on June 14. Can you give us a brief preview of the upcoming exhibition?

Gerhard Funk: TIME OUT .11 will once again focus strongly on the field of interactive installations. We will show nine very different works that have been created recently. A very nice work is “STRANGE_FACES” by Thomas Guggenberger, who won the Lentos Freunde Kunstpreis 2021 with it. When you approach the work you see three small moving mirrors standing in front of you. When you step into the sensitive field, the mirrors turn so that you see yourself in all three mirrors. But when a second or third person enters the sensitive field, the mirrors turn in such a way that you no longer see yourself in the mirror, but the other persons. This means that when I stand in the installation with another person, I see the other person in all three mirrors. A Kinect camera, which can recognize head positions and distance, acts as a sensorium. Thereby an angle is calculated how the mirror has to turn so that exactly I recognize the other person. The content-related component is that one is not always focused on oneself and only sees oneself in the mirror. The theme of the Lentos Freunde Kunstpreis was solidarity and that is exactly what the installation should express. One work that I think is fantastic and will be permanently exhibited in the Main Gallery of the Ars Electronica Center is “Watermap” by Daniel Fischer. In this work, you see the world map lying in front of you on a large plate. The continents are all filled with sand, and above the plate is a system of water tanks. Daniel permanently takes the weather data of the world and everywhere where it rains the system drops a drop. With this work you can see very well where in the world it rains a lot and where it rains less often. We always try to have a very balanced distribution of men and women in the selection of the work. Through a very concrete policy to the outside world and through certain accentuations that we have specifically set, we now have more women than men in our field of study, although it is a rather very technical study. I think it is very good that this has turned around in the years since this field of study has existed. At TIME OUT .11, there are works by five women and 4 men. Alice Hulan’s work “Gramophone – Unheard – Quotes from 1924-2018” was already shown last year at the Ars Electronica Festival at Johannes Kepler University. By operating the crank of the gramophone, quotations from political parties of the 1920s and 1930s, as well as quotations from the ranks of current government parties, are heard by the artist. While listening, it is no longer clear from which time which quote originates. In her bachelor’s thesis, Elisabeth Prast took a close look at the gene scissors CRISPR and developed a graphic novel about a vision of the future in which self-optimization through genetic engineering is part of everyday life. All of TIME OUT’s works stand on their own and do not refer to each other. We do not specify any topics for the semester projects. The students have to define their topics themselves, because we think that if I want to become an artistic person, I have to have something to say or know what I want to say. This process of self-definition can be a difficult one, but the result is all the more broad and individual.

Gerhard Funk, born in 1958, studied mathematics and art education in Linz and earned his PhD in Theoretical Computer Science at RISC Linz. In 1993 he moved to the Linz University of the Arts, where he established the teaching program for all students at the university in the field of digital media. Since 2004, he has been a professor at the Institute for Media and until October 2021 will be in charge of the bachelor’s program “Time-based and Interactive Media Art”, which he designed. In recent years, he developed the concept of “Cooperative Aesthetics” for the AEC’s Deep Space. Here, visitors can create a shared aesthetic spatial experience through their movements and through cooperation.